Chapter 176 Group A Streptococcus

Group A streptococcus (GAS), also known as Streptococcus pyogenes, is a common cause of infections of the upper respiratory tract (pharyngitis) and the skin (impetigo, pyoderma) in children and is a less common cause of perianal cellulitis, vaginitis, septicemia, pneumonia, endocarditis, pericarditis, osteomyelitis, suppurative arthritis, myositis, cellulitis, and omphalitis. These microorganisms also cause distinct clinical entities (scarlet fever and erysipelas), as well as a toxic shock syndrome and necrotizing fasciitis. GAS is also the cause of 2 potentially serious nonsuppurative complications: rheumatic fever (Chapters 176.1 and 432) and acute glomerulonephritis (Chapter 505.1).

Etiology

Epidemiology

Streptococcal pyoderma (impetigo, pyoderma) occurs most frequently during the summer in temperate climates, or year round in warmer climates, when the skin is exposed and abrasions and insect bites are more likely to occur (Chapter 657). Colonization of healthy skin by GAS usually precedes the development of impetigo. Because GAS cannot penetrate intact skin, impetigo usually occurs at the site of open lesions (insect bites, traumatic wounds, burns). Although impetigo serotypes may colonize the throat, spread is usually from skin to skin, not via the respiratory tract. Fingernails and the perianal region can harbor GAS and play a role in disseminating impetigo. Multiple cases of impetigo in the same family are common. Both impetigo and pharyngitis are more likely to occur among children living in crowded homes and in poor hygienic circumstances.

Clinical Manifestations

Respiratory Tract Infections

GAS is an important cause of acute pharyngitis (Chapter 373) and pneumonia (Chapter 392).

Scarlet Fever

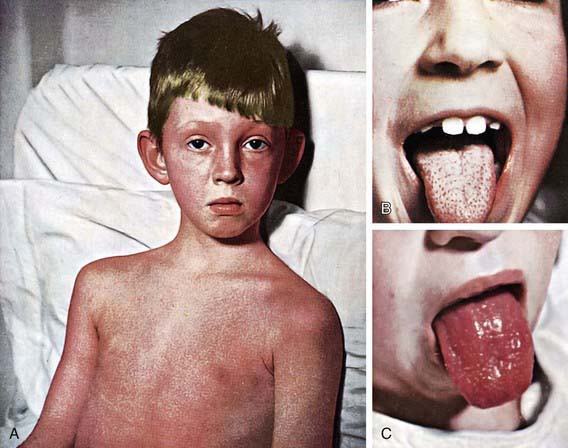

The rash appears within 24-48 hours after onset of symptoms, although it may appear with the first signs of illness (Fig. 176-1A). It often begins around the neck and spreads over the trunk and extremities. It is a diffuse, finely papular, erythematous eruption producing a bright red discoloration of the skin, which blanches on pressure. It is often more intense along the creases of the elbows, axillae, and groin. The skin has a goose-pimple appearance and feels rough. The face is usually spared, although the cheeks may be erythematous with pallor around the mouth. After 3-4 days, the rash begins to fade and is followed by desquamation, 1st on the face, progressing downward, and often resembling a mild sunburn. Occasionally, sheetlike desquamation may occur around the free margins of the fingernails, the palms, and the soles. Examination of the pharynx of a patient with scarlet fever reveals essentially the same findings as with GAS pharyngitis. In addition, the tongue is usually coated and the papillae are swollen (Fig. 176-1B). After desquamation, the reddened papillae are prominent, giving the tongue a strawberry appearance (Fig. 176-1C).

Impetigo

Impetigo (or pyoderma) has traditionally been classified into 2 clinical forms: bullous and nonbullous (Chapter 657). Nonbullous impetigo is the more common form and is a superficial infection of the skin that appears first as a discrete papulovesicular lesion surrounded by a localized area of redness. The vesicles rapidly become purulent and covered with a thick, confluent, amber-colored crust that gives the appearance of having been stuck on the skin. The lesions may occur anywhere but are more common on the face and extremities. If untreated, nonbullous impetigo is a mild but chronic illness, often spreading to other parts of the body, but occasionally is self-limited. Regional lymphadenitis is common. Nonbullous impetigo is generally not accompanied by fever or other systemic signs or symptoms. Impetiginized excoriations around the nares are seen with active GAS infections of the nasopharynx particularly in young children. However, impetigo is not usually associated with an overt streptococcal infection of the upper respiratory tract.

Vaginitis

GAS is a common cause of vaginitis in prepubertal girls (Chapter 543). Patients usually have a serous discharge with marked erythema and irritation of the vulvar area, accompanied by discomfort in walking and in urination.

Severe Invasive Disease

Invasive GAS infection is defined by isolation of GAS from a normally sterile body site and includes 3 overlapping clinical syndromes. The 1st is GAS toxic shock syndrome, which is differentiated from other types of invasive GAS infections by the presence of shock and multiorgan system failure early in the course of the infection (Table 176-1). The second is GAS necrotizing fasciitis characterized by extensive local necrosis of subcutaneous soft tissues and skin. The third is the group of focal and systemic infections that do not meet the criteria for toxic shock syndrome or necrotizing fasciitis and includes bacteremia with no identified focus, meningitis, pneumonia, peritonitis, puerperal sepsis, osteomyelitis, suppurative arthritis, myositis, and surgical wound infections.

Table 176-1 DEFINITION OF STREPTOCOCCAL TOXIC SHOCK SYNDROME

Clinical criteria

Hypotension plus 2 or more of the following:

Renal impairment

Coagulopathy

Hepatic involvement

Adult respiratory distress syndrome

Generalized erythematous macular rash

Soft tissue necrosis

Definite case

Clinical criteria plus group A streptococcus from a normally sterile site

Probable case

Clinical criteria plus group A streptococcus from a nonsterile site

Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

GAS is the most common cause of bacterial pharyngitis, accounting for 15-30% of the cases of acute pharyngitis in children. Groups C and G β-hemolytic streptococcus (Chapter 178) also produce acute pharyngitis in children. Arcanobacterium haemolyticum and Fusobacterium necrophorum are additional less common causes. Neisseria gonorrhoeae can occasionally cause acute pharyngitis in sexually active adolescents. Other bacteria such as Francisella tularensis and Yersinia enterocolitica as well as mixed infections with anaerobic bacteria (Vincent angina) are rare causes of acute pharyngitis. Chlamydia pneumoniae and Mycoplasma pneumoniae have been implicated as causes of acute pharyngitis, particularly in adults. Corynebacterium diphtheriae (Chapter 180) can cause pharyngitis but is rare because of universal immunization. Although other bacteria such as Staphylococcus aureus, Haemophilus influenzae, and Streptococcus pneumoniae are frequently cultured from the throats of children with acute pharyngitis, their etiologic role in pharyngitis has not been established.

Complications

Acute rheumatic fever (Chapter 176.1) and acute poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis (Chapter 505.1) are both nonsuppurative sequelae of infections with GAS that occur after an asymptomatic latent period. They are both characterized by lesions remote from the site of the GAS infection. Acute rheumatic fever and acute glomerulonephritis differ in their clinical manifestations, epidemiology, and potential morbidity. In addition, acute glomerulonephritis can occur after a GAS infection of either the upper respiratory tract or the skin, but acute rheumatic fever can occur only after an infection of the upper respiratory tract.

Pediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorders Associated with Streptococcus pyogenes (PANDAS)

PANDAS describes a group of neuropsychiatric disorders (particularly obsessive-compulsive disorders, tic disorders, and Tourette syndrome) for which a possible relationship with GAS infections has been suggested (Chapter 22). It has been demonstrated that patients with Sydenham chorea (a manifestation of acute rheumatic fever) frequently have obsessive-compulsive symptoms and that a subset of patients with obsessive-compulsive and tic disorders will have chorea as well as acute exacerbations following GAS infections. Therefore, it has been proposed that this subset of patients with obsessive-compulsive and tic disorders produce autoimmune antibodies in response to a GAS infection that cross react with brain tissue similar to the autoimmune response believed to be responsible for the manifestations of Sydenham chorea. It has also been suggested that secondary prophylaxis that prevents recurrences of Sydenham chorea might also be effective in preventing recurrences of obsessive-compulsive and tic disorders in these patients. Because of the proposed autoimmune mechanism, it has also been suggested that these patients may benefit from immunoregulatory therapy such as plasma exchange or intravenous immunoglobulin therapy. The possibility that PANDAS could represent an extension of the spectrum of acute rheumatic fever is intriguing, but it should be considered only as a yet-unproven hypothesis. Until carefully designed and well-controlled studies have established a causal relationship between PANDAS and GAS infections, routine laboratory testing for GAS to diagnose, long-term antistreptococcal prophylaxis to prevent, or immunoregulatory therapy (e.g., intravenous immunoglobulin, plasma exchange) to treat exacerbations of this disorder are not recommended (Chapter 22).

Barash J, Mashiach E, Navon-Elkan P, et al. Differentiation of post-streptococcal reactive arthritis from acute rheumatic fever. J Pediatr. 2008;153:696-699.

Bisno AL, Stevens DL. Streptococcal infections of skin and soft tissues. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:240-245.

Chan KH, Kraai TL, Richter GT, et al. Toxic shock syndrome and rhinosinusitis in children. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;135:538-542.

Choby BA. Diagnosis and treatment of streptococcal pharyngitis. Am Fam Physician. 2009;79:383-390.

Dale JB. Current status of group A streptococcal vaccine development. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2008;609:53-63.

Gerber MA, Baltimore RS, Eaton CB, et al. Prevention of rheumatic fever and diagnosis and treatment of acute streptococcal pharyngitis: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease Committee of the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young. Circulation. 2009;119:1541-1551.

Gerber MA, Shulman ST. Rapid diagnosis of pharyngitis caused by group A streptococci. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2004;17:571-580.

Jeng A, Beheshti M, Li J, et al. The role of β-hemolytic streptococci in causing diffuse, nonculturable cellulitis. Medicine. 2010;89(4):217-226.

Kaul R, McGeer A, Norby-Teglund A, et al. Intravenous immunoglobulin therapy in streptococcal toxic shock syndrome—a comparative observational study. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;28:800-807.

Kurlan R, Kaplan EL. The pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections (PANDAS) etiology for tics and obsessive-compulsive symptoms: hypothesis or entity? Practical considerations for the clinician. Pediatrics. 2004;113:883-886.

Lennon DR, Farrell E, Martin DR, et al. Once-daily amoxicillin versus twice-daily penicillin V in group A β-haemolytic streptococcal pharyngitis. Arch Dis Child. 2008;93:474-478.

Malhotra-Kumar S, Lammens C, Coenen S, et al. Effect of azithromycin and clarithromycin therapy on pharyngeal carriage of macrolide-resistant streptococci on healthy volunteers: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Lancet. 2007;369:482-490.

The Medical Letter. Extended release amoxicillin for strep throat. Med Lett. 2009;51:17.

Navarini S, Erb T, Schaad UB, et al. Randomized, comparative efficacy trial of oral penicillin versus cefuroxime for perinanal streptococcal dermatitis in children. J Pediatr. 2008;153:799-802.

Shulman ST, Tanz RR, Dale JB, et al. Seven-year surveillance of North American pediatric group A streptococcal pharyngitis isolates. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:78-84.

Stevens DL. Streptococcal toxic shock syndrome associated with necrotizing fasciitis. Annu Rev Med. 2000;51:271-288.

176.1 Rheumatic Fever

Clinical Manifestations and Diagnosis

Because no clinical or laboratory finding is pathognomonic for acute rheumatic fever, T. Duckett Jones in 1944 proposed guidelines to aid in diagnosis and to limit overdiagnosis. The Jones criteria, as revised in 1992 by the American Heart Association (AHA) (Table 176-2) are intended only for the diagnosis of the initial attack of acute rheumatic fever and not for recurrences. There are 5 major and 4 minor criteria and an absolute requirement for evidence (microbiologic or serologic) of recent GAS infection. The diagnosis of acute rheumatic fever can be established by the Jones criteria when a patient fulfills 2 major criteria or 1 major and 2 minor criteria and meets the absolute requirement. Even with strict application of the Jones criteria, overdiagnosis as well as underdiagnosis of acute rheumatic fever may occur. There are 3 circumstances in which the diagnosis of acute rheumatic fever can be made without strict adherence to the Jones criteria. Chorea may occur as the only manifestation of acute rheumatic fever. Similarly, indolent carditis may be the only manifestation in patients who 1st come to medical attention months after the onset of acute rheumatic fever. Finally, although most patients with recurrences of acute rheumatic fever fulfill the Jones criteria, some may not.

Table 176-2 GUIDELINES FOR THE DIAGNOSIS OF INITIAL ATTACK OF RHEUMATIC FEVER (JONES CRITERIA, UPDATED 1992)

| MAJOR MANIFESTATIONS* | MINOR MANIFESTATIONS | SUPPORTING EVIDENCE OF ANTECEDENT GROUP A STREPTOCOCCAL INFECTION |

|---|---|---|

| Carditis Polyarthritis Erythema marginatum Subcutaneous nodules Chorea |

Clinical features: Arthralgia Fever |

Positive throat culture or rapid streptococcal antigen test Elevated or increasing streptococcal antibody titer |

| Laboratory features: Elevated acute phase reactants: |

||

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate | ||

| C-reactive protein | ||

| Prolonged PR interval |

* The presence of 2 major or of 1 major and 2 minor manifestations indicates a high probability of acute rheumatic fever if supported by evidence of preceding group A streptococcal infection.

From Jones criteria, updated 1992. JAMA 268:2069–2073, 1992. Copyright American Medical Association.

Major Manifestations

Carditis

Carditis and resultant chronic rheumatic heart disease are the most serious manifestations of acute rheumatic fever and account for essentially all of the associated morbidity and mortality. Rheumatic carditis is characterized by pancarditis, with active inflammation of myocardium, pericardium, and endocardium (Chapter 432). Cardiac involvement during acute rheumatic fever varies in severity from fulminant, potentially fatal exudative pancarditis to mild, transient cardiac involvement. Endocarditis (valvulitis) is a universal finding in rheumatic carditis, whereas the presence of pericarditis or myocarditis is variable. Myocarditis and/or pericarditis without evidence of endocarditis is rarely due to rheumatic heart disease. Most cases consist of either isolated mitral valvular disease or combined aortic and mitral valvular disease. Isolated aortic or right-sided valvular involvement is uncommon. Serious and long-term illness is related entirely to valvular heart disease as a consequence of a single attack or recurrent attacks of acute rheumatic fever. Valvular insufficiency is characteristic of both acute and convalescent stages of acute rheumatic fever, whereas valvular stenosis usually appears several years or even decades after the acute illness. However, in developing countries where acute rheumatic fever often occurs at a younger age, mitral stenosis and aortic stenosis may develop sooner after acute rheumatic fever than in developed countries and can occur in young children.

Clinically, rheumatic carditis is almost always associated with a murmur of valvulitis. Several investigators and advisory groups have suggested that subclinical valvular regurgitation be accepted as evidence of rheumatic carditis. Subclinical valvular regurgitation is echocardiographically identified pathological mitral or aortic regurgitation inaudible to skilled auscultation. Although controversial, subclinical valvular regurgitation is not currently accepted as either a major or minor Jones criterion by the AHA in the guidelines for the diagnosis of acute rheumatic fever (Chapter 432).

Erythema Marginatum

Erythema marginatum is a rare (<3% of patients with acute rheumatic fever) but characteristic rash of acute rheumatic fever. It consists of erythematous, serpiginous, macular lesions with pale centers that are not pruritic (Fig. 176-2). It occurs primarily on the trunk and extremities, but not on the face, and it can be accentuated by warming the skin.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnoses of rheumatic fever include many infectious as well as noninfectious illnesses (Table 176-3). When children present with arthritis, a collagen vascular disease must be considered. Rheumatoid arthritis in particular must be distinguished from acute rheumatic fever. Children with rheumatoid arthritis tend to be younger and usually have less joint pain relative to their other clinical findings than those with acute rheumatic fever. Spiking fevers, lymphadenopathy, and splenomegaly are more suggestive of rheumatoid arthritis than acute rheumatic fever. The response to salicylate therapy is also much less dramatic with rheumatoid arthritis than with acute rheumatic fever. Systemic lupus erythematosus can usually be distinguished from acute rheumatic fever on the basis of the presence of antinuclear antibodies with systemic lupus erythematosus. Other causes of arthritis such as gonococcal arthritis, malignancies, serum sickness, Lyme disease, sickle cell disease, and reactive arthritis related to gastrointestinal infections (e.g., Shigella, Salmonella, Yersinia) should also be considered.

| ARTHRITIS | CARDITIS | CHOREA |

|---|---|---|

| Rheumatoid arthritis | Viral myocarditis | Huntington chorea |

| Reactive arthritis (e.g., Shigella, Salmonella, Yersinia) | Viral pericarditis | Wilson disease |

| Serum sickness | Infective endocarditis | Systemic lupus erythematosus |

| Sickle cell disease | Kawasaki disease | Cerebral palsy |

| Malignancy | Congenital heart disease | Tics |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | Mitral valve prolapse | Hyperactivity |

| Lyme disease (Borrelia burgdorferi) | Innocent murmurs | |

| Gonococcal infection (Neisseria gonorrhoeae) |

Complications

The arthritis and chorea of acute rheumatic fever resolve completely without sequelae. Therefore, the long-term sequelae of rheumatic fever are usually limited to the heart (Chapter 432).

The AHA has published updated recommendations regarding the use of prophylactic antibiotics to prevent infective endocarditis (Chapter 431). The AHA recommendations do not suggest routine prophylaxis any longer for patients with rheumatic heart disease. However, the maintenance of optimal oral health care remains an important component of an overall health care program. For the relatively few patients with rheumatic heart disease in whom IE prophylaxis remains recommended, such as those with prosthetic valves or prosthetic material used in valve repair, the current AHA recommendations should be followed (Chapter 431). These recommendations advise using an agent other than a penicillin to prevent IE in those receiving penicillin prophylaxis for rheumatic fever because oral α-hemolytic streptococci are likely to have developed resistance to penicillin.

Prevention

Secondary Prevention

The regimen of choice for secondary prevention is a single intramuscular injection of benzathine penicillin G (600,000 IU for children ≤60 lb and 1.2 million IU for those >60 lb) every 4 wk (Table 176-4). In certain high-risk patients, and in certain areas of the world where the incidence of rheumatic fever is particularly high, use of benzathine penicillin G every 3 wk may be necessary because levels of penicillin may decrease to marginally effective amounts after 3 wk. In the USA, the administration of benzathine penicillin G every 3 wk is recommended only for those who have recurrent acute rheumatic fever despite adherence to a 4-wk regimen. In compliant patients, continuous oral antimicrobial prophylaxis can be used. Penicillin V given twice daily and sulfadiazine given once daily are equally effective when used in such patients. For the exceptional patient who is allergic to both penicillin and sulfonamides, a macrolide (erythromycin or clarithromycin) or azalide (azithromycin) may be used. The duration of secondary prophylaxis is noted in Table 176-5.

Table 176-4 CHEMOPROPHYLAXIS FOR RECURRENCES OF ACUTE RHEUMATIC FEVER

| DRUG | DOSE | ROUTE |

|---|---|---|

| Penicillin G benzathine | 600,000 U for children, ≤60 lb 1.2 million U for children >60 lb, every 4 wk* |

Intramuscular |

| OR | ||

| Penicillin V | 250 mg, twice a day | Oral |

| OR | ||

| Sulfadiazine or sulfisoxazole | 0.5 g, once a day for patients ≤60 lb | Oral |

| 1.0 g, once a day for patients >60 lb | ||

| FOR PEOPLE WHO ARE ALLERGIC TO PENICILLIN AND SULFONAMIDE DRUGS | ||

| Macrolide or azalide | Variable | Oral |

* In high-risk situations, administration every 3 weeks is recommended.

From Gerber MA, Baltimore RS, Eaton CB, et al: Prevention of rheumatic fever and diagnosis and treatment of acute streptococcal pharyngitis: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease Committee of the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, Circulation 119:1541–1551, 2009.

Table 176-5 DURATION OF PROPHYLAXIS FOR PEOPLE WHO HAVE HAD ACUTE RHEUMATIC FEVER: RECOMMENDATIONS OF THE AMERICAN HEART ASSOCIATION

| CATEGORY | DURATION |

|---|---|

| Rheumatic fever without carditis | 5 yr or until 21 yr of age, whichever is longer |

| Rheumatic fever with carditis but without residual heart disease (no valvular disease*) | 10 yr or until 21 yr of age, whichever is longer |

| Rheumatic fever with carditis and residual heart disease (persistent valvular disease*) | 10 yr or until 40 yr of age, whichever is longer, sometimes lifelong prophylaxis |

* Clinical or echocardiographic evidence.

From Gerber MA, Baltimore RS, Eaton CB, et al: Prevention of rheumatic fever and diagnosis and treatment of acute streptococcal pharyngitis: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease Committee of the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, Circulation 119:1541–1551, 2009.

Carapetis JR, McDonald M, Wilson NJ. Acute rheumatic fever. Lancet. 2005;366:155-168.

Dajani AS, Ayoub E, Bierman FZ, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis of rheumatic fever: Jones criteria, 1992 update. JAMA. 1992;268:2069-2073.

Gerber MA, Baltimore RS, Eaton CB, et al. Prevention of rheumatic fever and diagnosis and treatment of acute streptococcal pharyngitis: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease Committee of the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young. Circulation. 2009;119:1541-1551.

Lennon D. Acute rheumatic fever in children. Paediatr Drugs. 2004;6:363-373.

Marijon E, Ou P, Celermajer DS, et al. Prevalence of rheumatic heart disease detected by echocardiographic screening. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:470-476.

Martin JM, Barbadora KA. Continued high caseload of rheumatic fever in western Pennsylvania: possible rheumatogenic EMM types of Streptococcus pyogenes. J Pediatr. 2006;149:58-63.

Miyake CY, Gauvreau K, Tani LY, et al. Characteristics of children discharged from hospitals in the United States in 2000 with the diagnosis of acute rheumatic fever. Pediatrics. 2007;120:503-508.

Shulman ST, Stollerman G, Beall B, et al. Temporal changes in streptococcal M protein types and the near-disappearance of acute rheumatic fever in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:441-447.

Tani LY, Veasy LG, Minich LL, et al. Rheumatic fever in children younger than 5 years: is the presentation different? Pediatrics. 2003;112:1065-1068.

Walker AR, Tani LY, Thompson JA, et al. Rheumatic chorea: relationship to systemic manifestations and response to corticosteroids. J Pediatr. 2007;151:679-683.

Zomorrodi A, Wald ER. Sydenham’s chorea in Western Pennsylvania. Pediatrics. 2006;117:e675-e679.

of the hospital beds in the USA were occupied by patients with acute rheumatic fever or its complications. By the 1940s, the annual incidence of acute rheumatic fever had decreased to 50/100,000, and over the next 4 decades, the decline in incidence accelerated rapidly. By the early 1980s, the annual incidence in some areas of the USA was as low as 0.5/100,000 population. This sharp decline in the incidence of acute rheumatic fever has been observed in other industrialized countries as well.

of the hospital beds in the USA were occupied by patients with acute rheumatic fever or its complications. By the 1940s, the annual incidence of acute rheumatic fever had decreased to 50/100,000, and over the next 4 decades, the decline in incidence accelerated rapidly. By the early 1980s, the annual incidence in some areas of the USA was as low as 0.5/100,000 population. This sharp decline in the incidence of acute rheumatic fever has been observed in other industrialized countries as well.