Gross Description and Processing of Specimens

General Aspects of Gross Decription and Cutting in of Specimens

Endometrial Biopsies and Curettings

Uterus Removed for Benign or Functional Disease

Introduction

The surgical pathologist reports the histopathologic diagnosis and specific information relating to prognosis and treatment. Therefore, one must have sufficient familiarity with the management of gynecologic and obstetric disorders to assure that the pathology report communicates the clinically relevant information. This chapter provides an approach to the processing of gynecologic and obstetric tissue specimens. The techniques of gross examination and the method of reporting the pathologic findings are guided by the clinical principles on which patient management is based. Several textbooks are now devoted entirely to this topic.1–3

The main purpose of a biopsy is to provide a histologic diagnosis that will guide management. Since biopsy specimens tend to be small and without specific gross features, the major pathology resides in the histology. The gross description is important mainly to ensure that what is received in the pathology laboratory and submitted for microscopic examination matches the slides returned from the histology laboratory for the pathologist to examine. Disparity between the findings on a slide and those expected based on the gross description is often the only clue that a slide or block may have been mislabeled. A good gross description therefore should be precise and brief. Examples of good descriptions are ‘3 ovoid fragments 2 to 4 mm in diameter,’ ‘multiple shreds of tissue 5 cm in aggregate,’ or the exact size given in three dimensions. For some specimens, it is also useful to note whether it is largely blood, mucin, or tissue.

Section Codes and the Report

Location of Section Codes in the Report

Most pathologists prefer a section code summary at the end of the gross text while some prefer entering block codes within the gross text. In either case, the report must be clear, both to the pathologist and to any person who at a later time will need to utilize the report. Block summaries, if used, may duplicate substantial parts of the gross, but cannot be used in its place. Including the block submission within the body of the gross description may be easier and more efficient for the person cutting in the specimen: ‘The borders in one region are sharp and distinct from the surrounding myometrium (Block B10) while elsewhere it blends into the adjacent myometrium (Block B11).’ However, having a section key at the end of the dictation may make histologic examination easier and more efficient. If the block codes are listed sequentially at the end of the report, the specific site and feature identified require presentation in sufficient detail so that the reader can easily link the gross description with the slide. Using the example above, it would be inappropriate for the coding block at the end to state that B10 and B11 are myometrium as it is unclear which section has the sharp borders and which has blurred borders. A section code at the end might better read, ‘B10 Myometrium, sharply circumscribed medial border, B11 Myometrium, blurred indistinct borders.’

General Aspects of Gross Decription and Cutting in of Specimens

Gross Description

The gross description, especially of small specimens, should conclude by stating how much of the tissue has been processed for microscopic examination. This is especially important in the case of endometrial curettings removed for a suspected intrauterine pregnancy where neither chorionic villi nor other tissues of fetal origin are found and all of the tissue has been submitted. Specify the number of each type of block sampled and from where each was obtained. An example of a useful gross description is ‘The endometrium, which is 2 mm thick, discloses no obvious tumor. The entire endometrium including the superficial myometrium is blocked and submitted in toto.’

Synoptic Checklists

As the complexity of information contained in reports increases and tumor cases are accessioned into trials with specific entry criteria, checklists are being used with increasing frequency to record and evaluate the details of operative and pathologic findings consistently. A full listing of College of American Pathologists specimen processing protocols, including synoptic checklists, is available online at www.cap.org.

Vulva

Excisional Biopsies

Biopsies of the vulva should be handled like skin biopsies. Assess the deep and lateral resection margins. If the surgeon has placed a suture for orientation, inking (often in several colors) facilitates recognition on microscopic examination.4

Wide Local Excision

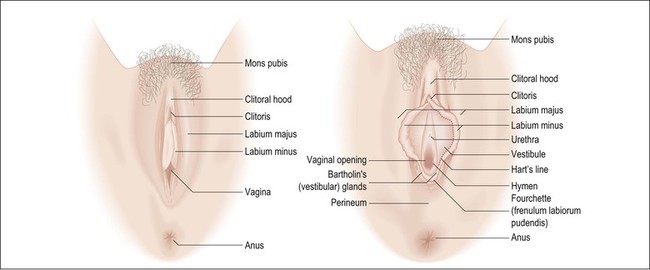

In general, wide local excisions are performed for noninvasive neoplasms such as vulvar intraepithelial neoplasm (VIN) 3 or Paget disease of the vulva, as well as superficially invasive (less than 1 mm) stage 1 carcinomas. Lymph node dissections are added for stage 1B carcinomas (greater than 1 mm invasive). Orientation is critical in these specimens and, if not clearly indicated, consultation with the surgeon may be required. Operative specimens often include labia minora and majora, clitoris, perineal body, and perianal tissue (Figure 35.1). Describe and measure the lesions, distances to resection margins, and the anatomic structures involved. Examine the coloration and surface texture carefully as intraepithelial lesions are subtle, typically red-brown to white and roughened.

As intraepithelial lesions are often multifocal and difficult to discern macroscopically, all surgical peripheral and deep resection margins should be evaluated microscopically. Sections parallel to margins (‘tangential’) may be taken to evaluate the excision lines; however, one difficulty commonly encountered in parallel sections for evaluation of margins is to determine if tumor found in the slide truly involves the margin or was from the inner face, and therefore not a true representation of the margin.

For discrete tumors, such as squamous cell carcinoma, multiple full thickness sections perpendicular to the skin surface and radiating outward from the lesion are advantageous as the central lesion, margins, and intervening areas can be included in one slide and tumor close to the margin is easy to evaluate (Figure 35.2). Facilitate sectioning by pinning the specimen on a corkboard or a block of paraffin and fix for several hours or overnight. Diagrams or photographs are often useful.

Simple (or Total) Vulvectomy

This includes the entire vulva and subcutaneous fat (dissection to deep fascia). It is typically performed for noninvasive neoplasms that widely involve the vulva. Pin, fix, and section the specimen at 0.5 cm intervals to evaluate for invasive carcinoma. Typically, the extent of Paget disease exceeds that visible macroscopically as occult foci are often present within normal-appearing skin. The resection margins must be thoroughly evaluated.2,5

Radical Vulvectomy

Radical vulvectomy consists of vulva excised to the deep fascia of the thigh, the periosteum of the pubis, and the inferior fascia of the urogenital diaphragm. It is most commonly performed together with at least an inguinal lymph node dissection, which may be included en bloc with the vulvectomy. Total radical vulvectomies have largely been replaced in favor of more limited excisions, but sufficient to completely excise the primary tumor with a minimum 2 cm margin. Radical total vulvectomies are now performed primarily for large and/or aggressive tumors. The gross description should include the size, location, depth of invasion, and all resection margins, including perianal and vaginal margins. Sections should include the tumor, showing the maximum depth of invasion, labia majora and minora, clitoris, distal urethra, resection margins including the vaginal margin, and all lymph nodes. Separate lymph nodes into superficial and deep groups, and submit all lymph nodes entirely for histologic examination (unless grossly positive; in that case a representative section is sufficient). Invasive vulvar neoplasms are typically solitary in contrast to intraepithelial lesions, which are often multifocal. Consequently, evaluation of resection margins can be largely limited to the margins closest to the tumor. The report should include microscopic diagnosis, tumor grade, dimensions, location and maximum depth of invasion, presence of lymphatic invasion, number and location of involved lymph nodes, and distance to resection margins. Diagrams and/or photographs may be useful aids.

Cervix

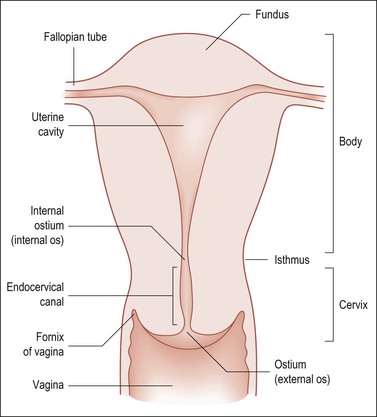

The cervix may be sampled as punch biopsies, endocervical curettages, or cone biopsies (various methods), or removed entirely in total hysterectomy specimens or radical hysterectomy specimens.6

Cervical Cone Biopsy/Excision and Trachelectomy

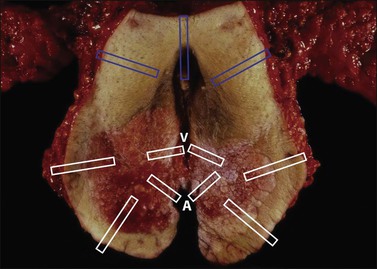

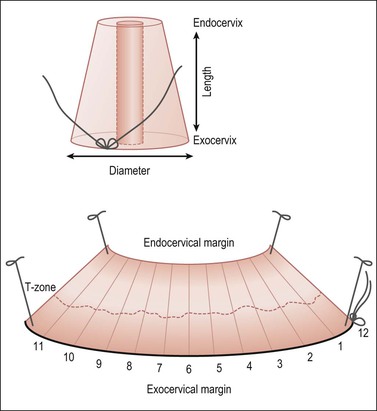

The surgical pathologist can limit the gross description to the measurements of the specimen and any obvious lesion. The measurements should include the cranial–caudal distance (the height or length of the cone specimen), the diameter if the specimen is not opened (Figure 35.3), or circumference and thickness if received opened. For a trachelectomy specimen, the presence of vaginal cuff should be documented and measured.

Figure 35.3 Cervical cone biopsy. The craniocaudal length and exocervix (portio) diameter should be measured. The exocervical and endocervical margins need to be separately assessed (with differential inking). Open the cone along its length through the canal, at the 12 o’clock position marked by the surgeon with a suture, or a random starting point if not oriented. Block in the entire specimen sequentially cut so each piece represents the canal lining, and surgical margins. The specimen is shown here endocervical mucosa up, with a dashed line marking the T-zone.

Blot dry the tissue and apply ink sparingly. Open the specimen at 12 o’clock, and pin the tissue on a corkboard with the mucosa facing up. Fixation for 3 hours before cutting is usually adequate. Serially cut sections should be sequentially submitted in cassettes numbered consecutively. Submit the entire specimen in a clockwise direction beginning at 12 o’clock (Figure 35.3). Convenience and economy dictate placing two or three sections per cassette.

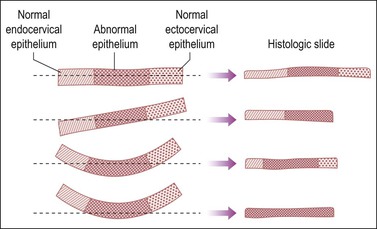

Both the ectocervical and endocervical edges of the cone specimen need to be assessed. This can prove to be problematic if a specimen is bowed and cut tangentially (Figure 35.4).

Uterine Corpus

Endometrial Biopsies and Curettings

Tissue from an endometrial biopsy (curettage or outpatient sample) should be submitted in its entirety. The gross description should estimate the aggregate volume. The cassettes should be packed loosely to permit proper fixation and dehydration. Wrap specimens in fine Shandon mesh/tea bags or equivalent and document in the dictation that the whole specimen is included.7

Uterus Removed for Benign or Functional Disease

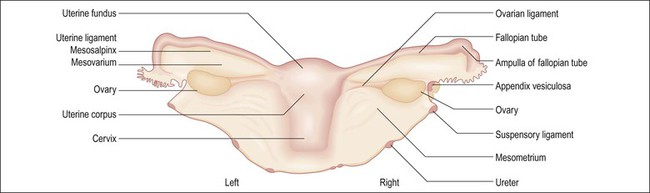

List specimens received, including whether the adnexae are attached or separate. Several methods are available for orientation. One easy method to determine laterality is to lift the specimen by the two ovaries, which will be posterior to the fallopian tubes (Figure 35.5). Another method that is useful in the absence of adnexae is to observe the peritoneal reflections. The posterior uterine peritoneal surface covers a larger area and extends farther down toward the cervix in a V-shaped configuration, whereas, anteriorly, it ends higher over the bladder and in a more flat or smooth U shaped reflection edge.

Figure 35.5 The uterus and adnexa, posterior aspect. One easy method for determining laterality is to suspend the two ovarian ligaments, which are posterior to the fallopian tube and therefore define right from left.

Weigh the specimen without adnexae (i.e., subtract the estimated adnexal weight). Nomenclature is given in Figure 35.6.

Examine the uterine serosa, particularly the posterior surface, for adhesions or brown hemosiderin deposits, so-called ‘powder burns,’ which may indicate endometriosis, and small vesicles or gritty implanted foci suggestive of borderline serous tumor, endosalpingiosis, ovarian cancer, or psammoma body implants. Examine the exocervix for lacerations, scarring, ulcerations, and nabothian cysts.

Before opening the uterus, probe the cervical canal and endometrial cavity to establish the canal’s patency; this also facilitates opening the uterus. With scissors cut from the cervical os to the cornu along one lateral margin to the fundal top and then repeat on the opposite side. Another option is to pass a pair of long fine forceps through the cervical os all the way to the fundus and cut the uterus open by using a long knife between the forceps blades. These methods ensure that the endometrial cavity will be exposed, with the anterior and posterior endomyometrium intact.

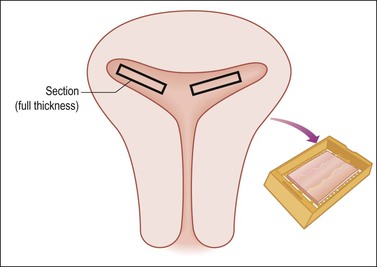

Measure the average thickness of the endometrium and assess whether it is atrophic, polypoid, lush, or hemorrhagic, and smooth or rough surfaced. Record polyp measurements and location (fundic, anterior/posterior, near LUS, etc.). Evaluate the myometrium and state its average and maximum thickness. Focally or asymmetrically thickened myometrium, small cysts, or hemorrhage suggests adenomyosis. For a normal cervix, usually one section is adequate if it includes the entire wall to involve the endocervix, squamocolumnar junction, exocervix, and paracervical soft tissue. Some pathologists prefer one section each of the anterior and posterior lips. The section through the endometrium, if the lesion is benign, should be 2 cm long and include the full endometrial thickness and a wedge of myometrium with serosa if not too thick. Generally, two sections, one each from the anterior and posterior (or right and left) corpus, suffice if the woman is in reproductive years and one if the uterus is atrophic and the woman is in the postmenopausal years (Figure 35.7). If there is no apparent pathology and the preoperative diagnosis is pain or dysfunctional uterine bleeding, then increase the number of sections to at least four that are full thickness, and include a posterior LUS section with peritoneal reflection. It is surprising how frequently adenomyosis is confined to only a single area in a single slide.

Figure 35.7 Sampling of the uterine body for complaint of bleeding where no obvious gross disease is present (e.g., occult adenomyosis). Two full thickness sections anteriorly and two posteriorly (shown here) extensively and efficiently sample the endometrium and myometrial wall.

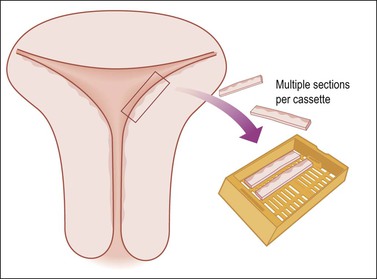

Uteri removed for endometrial hyperplasia or precancerous lesions require multiple sections of the endomyometrium to exclude carcinoma. For example, six sections, each 2 cm long and cut as wedges, can usually fit into two or three cassettes (Figure 35.8). If the uterus is not enlarged, this number of sections often samples 75% of the endometrium. Some pathologists prefer to block in the entire endometrium with sections through to the serosa so as not to miss the possibility of invasive cancer and be able to measure the depth of invasion.

Figure 35.8 Efficient but extensive sampling of the uterine body for endometrial hyperplasia or endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia.

Uteri removed for leiomyomas should have documented the number of leiomyomas present, their location (submucosal, intramural, subserosal) and size (e.g., ‘ten measuring ≤ 1 cm and two measuring 13 and 18 cm in diameter’). If submucosal, state whether the tumor distorts the endometrial cavity or protrudes into the lower uterine canal or cervix. Each leiomyoma should be sectioned and examined grossly, but not necessarily microscopically. If all are small, white, firm, whorled, with well-circumscribed margins, and lack areas that are soft, necrotic, or hemorrhagic, even one block can be sufficient. Routine microscopic examination of every typical leiomyoma is unnecessary. Conversely, as leiomyosarcomas generally grow as a single nodule or mass and exhibit soft and degenerative areas, any suspicious areas should be thoroughly sampled. As a rule, of the suspicious regions take one microscopic section per 1 cm of the nodule’s greatest dimension, for these areas usually yield more useful information. The transition between smooth muscle tumors and surrounding myometrium is the preferred site for histologic sampling. ‘Random’ sections of grossly typical leiomyomas generally are of little use. For myomectomy specimens, transect each leiomyoma and take one section of each if the number is not excessive, or more if any areas are suspicious. More commonly, hysterectomies for benign conditions are being performed laparoscopically with morcellation. In this situation, the morcellated uterus should be weighed and examined to identify fragments with endometrium, serosa, cervix if present, and lesional tissue (leiomyomas, adenomyosis, etc.), and a conservative number of blocks submitted.

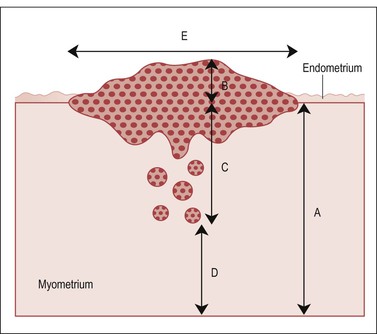

Malignant Uterine Disease

The gross description must include the size, location, distribution (focal or diffuse), and shape (sessile or polypoid) of the lesion. For example, ‘a 6 × 5 cm sessile anterior endometrial tumor involves the anterior LUS but not the endocervix. The tumor grossly invades 5 mm and maximally 10 mm into a 23 mm thick wall (approximately 45% of the myometrial thickness).’ If the tumor is polypoid and protrudes into the endometrial cavity, identify the borders of the adjacent normal endometrium, draw an imaginary line between, and then report measurements above and below the line. Thus the 1 cm thick tumor, which protrudes 7 mm into the endometrial cavity, penetrates 3 mm into the superficial myometrium (Figure 35.9). Describe and sample the uninvolved endometrium, including its relationship with the tumor and adjacent myometrium. At least one microscopic section should permit measurement of the greatest depth of tumor invasion, and may be submitted as two blocks if the full myometrial thickness does not fit in one cassette (Figure 35.10). For intramural tumors, describe and sample the interface between the tumor and myometrium (circumscribed, irregular, or infiltrative) and note any worm-like extrusions of tumor in surrounding tissues that could represent grossly involved lymphatic/vascular channels (seen most commonly in endometrial stromal sarcomas and intravenous leiomyomatosis). An endometrium previously ablated for precancerous disease need not be entirely submitted; representative sections in addition to any grossly identifiable lesion should be submitted for microscopic examination.

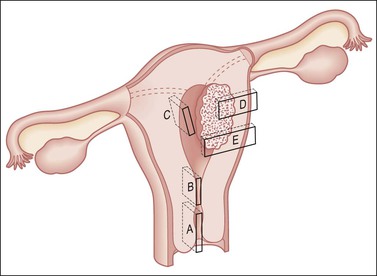

Figure 35.9 Measurements of depth to which tumor invades. A, full thickness of myometrial wall, measured from the native endometrial–myometrial junction. This landmark may require examination of the endometrium–myometrium interface adjacent to the tumor. B, component of tumor exophytic and rising above an imaginary line drawn between adjacent normal endometrium. C, depth of invasion. D, tumor-free zone. E, width of tumor. We generally report a tumor as measuring n × n × n and ‘invading through X percentage of the myometrial thickness’ (percentage of myoinvasion = 100 × C/A).

Figure 35.10 Technique for sectioning the uterus. The sampling shown is for the posterior half, and would be mirrored in the anterior half, producing double the number of sections. It includes cervix (A); margins adjacent and deep to a cancer (D, E); LUS and uppermost endocervix (B), for example, to determine whether an endometrial cancer involves the cervix, thus upstaging it; the wall for adenomyosis (C); and endometrium with areas partially or totally seemingly free of tumor. In sampling the LUS, a posterior midline section extending to include the peritoneum (B) will enable evaluation of potential ‘drop metastases’ within the cul-de-sac peritoneal reflection.

Lymphadenectomy may be included in the staging of endometrial carcinoma. Studies have shown that higher numbers of removed pelvic and para-aortic lymph nodes (12 or greater) are more prognostically powerful, particularly when negative.8 Thus, careful dissection of lymphadenectomy specimens, with submission of all possible lymph nodes, is necessary.

Fallopian Tube

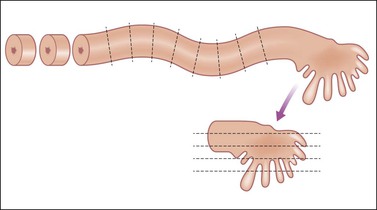

Many fallopian tube specimens (salpingectomy) are performed in conjunction with oophorectomy and hysterectomy, especially in older women in whom it is no longer necessary to preserve fertility. Typically in these cases, there is no grossly identifiable lesion in the fallopian tubes. The overall length and diameter of the tube should be measured. Peritubal cysts and adhesions should be documented. The fimbriae should be examined for thickening or irregularities. Small, grossly undetectable carcinomas have been shown to occur in the fimbriated end of the fallopian tube not infrequently. For this reason, regardless of the indication for salpingectomy, portions of the fimbria should be included in microscopic sampling. If there is significant concern for an occult tubal carcinoma, the entire fimbriated end can be submitted for histologic examination according to the SEE-FIM (sectioning and extensively examining the fimbriated end) protocol (Figure 35.11).6

Figure 35.11 SEE-FIM protocol for cutting in a fallopian tube where comprehensive sampling is desired to assess possible occult epithelial lesions, such as those seen in BRCA patients. Cross sections cut at ~3 mm intervals of the length of the tube, and the fimbriated end amputated and cut in the longitudinal axis at 1–2 mm intervals. The entire fimbria is submitted.

Prophylactic Salpingectomy (with or Without Oophorectomy)

Another increasingly common indication for salpingectomy is prophylaxis for patients who have BRCA1/2 mutations, a personal history of breast cancer, or strong family history of breast and/or tubo-ovarian cancer. Typically the specimen is grossly unremarkable; however, these fallopian tubes, along with the corresponding ovaries, should be submitted entirely for histologic examination according to the SEE-FIM protocol.9 The proximal fallopian tube is serially sectioned at ~3 mm intervals, stopping approximately 1 cm before the distal-most portion of the fallopian tube. The fimbria should be sectioned longitudinally to maximize fimbrial plicae histologic examination (Figure 35.11).

Tubal Neoplasm

Recent studies have shown that tubal cancer is more common than was initially appreciated, partly due to the fact that fallopian tubes historically were not thoroughly sampled for histologic examination.9 Tubal carcinomas behave similarly to ovarian carcinoma and frequently appear as a solid mass in the wall of a grossly dilated tube, but may sometimes only be identified upon microscopic examination. When grossly identifiable, its size, location, and extent, with reference to other pelvic structures, should be documented. Transverse sections through the full tubal wall permit determination of the depth of penetration/invasion, which is an essential component to the pathology report.

Ovary

The pathologist may receive ovarian tissue from patients in a variety of clinical circumstances, each of which determines the manner in which the specimen is handled. If oophorectomy is performed in association with a hysterectomy with no expectation or realization of ovarian pathology, a simple ‘routine’ pathologic examination will usually suffice. In contrast, ovaries excised for prophylaxis or suspected or proven neoplasms may require several different specialized analyses in addition to histologic assessment. In some circumstances, e.g., ovarian failure, it may be appropriate to have a preoperative consultation to discuss the appropriate site and size of the biopsy and its immediate handling in the operating room in order to optimize analysis of the clinical problem.10

General Rules

• The specimen should be examined fresh or at most fixed for a short period.

• It should be weighed and measured.

• The external surface should be inspected for adhesions, excrescences, hemorrhage, or hemosiderin.

• Sections should be taken perpendicularly through the adhesions to include the capsule and parenchyma to determine whether or not the adhesions are due to inflammation or neoplasm. Note the presence of a corpus luteum, cystic follicles (if excessive in number), or cysts. Their combined absence may indicate an otherwise unexpected diffuse metastasis.

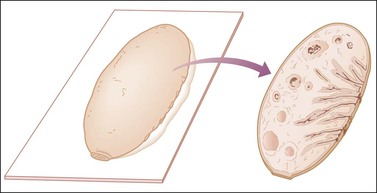

• Residual uninvolved ovary should be incised by parallel transverse cuts (Figure 35.12).

Figure 35.12 Technique for sectioning ovary in the absence of abnormalities. The cross section shows cortex, medulla, and hilum.1

• One block is sufficient from a macroscopically normal ovary, but this should include cortex, medulla, and hilus, conveniently sampled by a single section through the middle of the ovary. An exception to this rule is in prophylactic bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy specimens, in which case the entire specimen should be submitted for histologic examination.

Microscopic Sections

Ink can be useful to document the tumor’s serosal surface. The best blocks of tumor are where the tissue is viable. Generally, about one block per 2 cm of greatest tumor dimension will suffice to document the tumor process. It is common in cystic mucinous neoplasms for any single tumor to have large areas that are benign or borderline, with only few areas that are unequivocally malignant. Commonly, areas with multilocular thin-walled cysts are benign, or at most of borderline malignancy. Areas that are more solid are usually borderline and sometimes frankly malignant. Quite commonly, only 10% of solid areas may show unequivocal malignancy, which in a 10 cm tumor translates to only two slides with malignancy out of 20 sampled. Search diligently for solid areas and sample them thoroughly. Unilocular cysts with a smooth inner-wall lining may be large, but require few sections. Membrane rolls composed of extensive quantities of cyst wall tissue can be examined if the wall is made into a membrane roll and a cross-section slide prepared (Figure 35.13).

Germ cell tumors should be sampled extensively, especially if they appear grossly heterogeneous. If there is a history or clinical suspicion of intersex an X-ray for calcifications may indicate an area of gonadoblastoma. These regions should be sampled thoroughly. All variations in the gross appearance such as foci of hemorrhage or necrosis should be specifically sampled as they may represent different tumor types, e.g., foci of embryonal carcinoma or yolk sac tumor (YST) arising in association with a dysgerminoma.

Staging Operations

1. Evaluate the ovarian mass to exclude metastasis from colon, stomach, or elsewhere. Note penetration through capsule and biopsy areas of adherence.

2. Obtain ascitic fluid or saline washings for cytology.

3. Inspect all peritoneal surfaces. Prove that apparent implants are malignant by frozen section, or submit multiple samples for permanent section, or both. Inspect the diaphragm, with biopsy of visible lesions or scrapings for cytology.

4. Confirm accuracy of apparent stage 1 or 2 disease by generous omental biopsy and biopsy of palpable pelvic and para-aortic nodes.

5. After excision, mark the specimen, indicating for the pathologist the site of rupture and/or area(s) of adherence. Record residual disease location and estimate extent.

Specimens submitted for pathologic examination are likely to include the following:

• Uterus with attached or separately submitted adnexa, preferably delivered fresh to the pathologist immediately. Carefully examine the whole specimen noting the excisional margins if necessary. Complete the assessment of the ovaries as recommended previously. Before fixation, open the uterine cavity, keeping in mind the possibility of a coexisting endometrial carcinoma or hyperplasia. Scrutinize the uterine serosal surface for tumor deposits and section any adhesions to exclude microscopic metastases (since these will raise the International Federation of Gynecologists and Obstetricians stage from at least stage 1 to at least stage 2A).

• Omentum. Slice finely, looking for tumor deposits and block these. If none is found, sample any unusually firm areas (usually fibrous adhesions which may or may not be associated with microscopic tumor deposits). One or two blocks should be sufficient. In over 20% of cases, the grossly normal omentum will disclose microscopic foci of tumor.

• Pelvic and/or para-aortic lymph nodes. Submit all lymphoid tissue.

• Peritoneal biopsies. These are often very small and should be handled accordingly, using a mesh bag if necessary.

• Peritoneal washings. The surgeon collects these by saline irrigation from the left and right paracolic gutters, subdiaphragmatic region, and pouch of Douglas. These fluids should be processed by cytology; evaluation of cytospins, smears, liquid-based cytology techniques (e.g. ThinPrep), and cell block as deemed appropriate by the laboratory. Ascitic fluid is treated similarly.

Fetus and Placenta

Second Trimester Fetus

In many institutions, special permission is required to examine a fetus nearing viability. Statutes variously define the cut-off as a fetus older than 20 weeks’ gestation, greater than 15 cm crown–rump length, or greater than 300 g weight. Regardless of gestational age, the placenta can be submitted as a surgical pathology specimen.11

Physical integrity (intact, fragmented) and autolytic state (well preserved, macerated) of the fetus should be recorded. Extent of fetal maceration may be helpful in documentation of the time frame of fetal demise. Measure and record the fetal weight, crown–heel length, crown–rump length, and head circumference. Other common measurements include foot length, thorax, and abdominal circumferences. Sex can usually be determined by external examination. If the genitalia are ambiguous, then describe them as such. Never give a ‘best guess’ for sex assignments. Look for obvious external anomalies, and if present consider whether they may be part of a multi-feature syndrome that requires targeted examination of visceral abnormalities. More subtle ones are difficult to observe in early gestation. Measure the attached cord length and state the number of blood vessels. Describe the skin surface and, after the body is opened, observe the organs in situ. Determine situs and note any obvious abnormalities. Retrieve the gonads and place them in a mesh bag at this point. Take sections of various organs. Weighing organs that are part of a fragmented surgical specimen is often a futile exercise. Microscopic sampling should include each lobe of lung, both gonads, and small sections of every other organ including stomach and other various parts of gastrointestinal tract and skin. Macerated fetuses are difficult to sample adequately because of the severe softening of the tissues; submit sections of more solid tissue (lungs, heart, kidneys). Often the entire examination consists of no more than three cassettes filled with tissue.

Placenta

Abnormalities of the placenta are frequently associated with adverse outcomes in either the fetus or the mother.11,12 Examination of the placenta is not routinely performed in most institutions unless specific indications are present. The CAP practice guidelines include recommendations of indications for placental examination (Table 35.1). To determine which placentas should be examined, remember the three funnies: funny mother, funny infant, funny disease. This should lead to the examination of about one in three placentas, although in practice fewer are examined (about one in five).11

Table 35.1

Recommended Maternal Indications (General Agreement)

Systemic disorders with clinical concerns for mother or infant (e.g., severe diabetes, impaired glucose metabolism, hypertensive disorders, collagen disease, seizures, severe anemia; <9 g)

Premature delivery ≤34 weeks’ gestation

Peripartum fever and/or infection

Unexplained third trimester bleeding or excessive bleeding >500 cm3

Clinical concern for infection during this pregnancy (e.g., human immunodeficiency virus, syphilis, cytomegalovirus, primary herpes, toxoplasma, rubella)

Severe oligohydramnios

Unexplained or recurrent pregnancy complication (e.g., intrauterine growth retardation, stillbirth, spontaneous abortion, premature birth)

Invasive procedures with suspected placental injury

Abruption

Non-elective pregnancy termination

Thick and/or viscous meconium

Other Maternal Indications (Less General Agreement)

Premature delivery >34–37 weeks’ gestation

Severe unexplained polyhydramnios

History of substance abuse

Gestational age ≥42 weeks

Severe maternal trauma

Prolonged (>24 hours) rupture of membranes

Recommended Fetal/Neonatal Indications

Admission or transfer to other than a level 1 nursery

Stillbirth or perinatal death

Compromised clinical condition defined as any of the following: cord blood pH, <7.0; Apgar score, ≤6 at 5 minutes; ventilatory assistance, >10 minutes; or severe anemia, hematocrit <35%

Hydrops fetalis

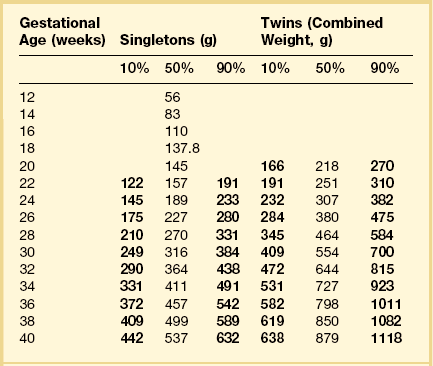

Birthweight <10th percentile

Seizures

Infection or sepsis

Major congenital anomalies, dysmorphic phenotype, or abnormal karyotype

Discordant twin growth >20% weight difference

Multiple gestation with same-sex infants and fused placentas

Other Fetal/Neonatal Indications (Less General Agreement)

Birthweight >95th percentile

Asymmetric growth

Multiple gestation without other indication

Vanishing twin beyond the first trimester

Recommended Placental Indications

Physical abnormality (e.g., infarct, mass, vascular thrombosis, retroplacental hematoma, amnion nodosum, abnormal coloration, or opacification, malodor)

Small or large placental size or weight for gestational age

Umbilical cord lesions (e.g., thrombosis, torsion, true knot, single artery, absence of Wharton’s jelly)

Total umbilical cord length <32 cm at term

Other Placental Indications (Less General Agreement)

Abnormalities of placental shape

Long cord (>100 cm)

Marginal or velamentous cord insertion

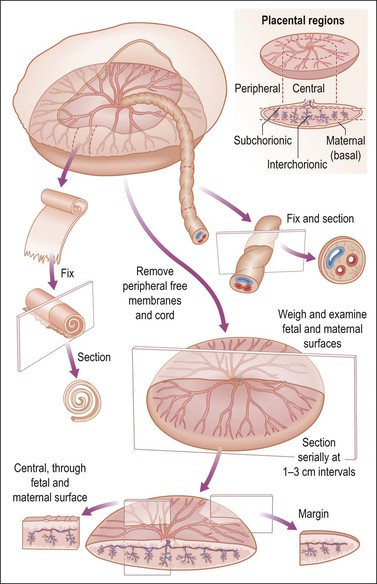

Remove the free membranes and cord, leaving the fetal side of the disc undisturbed, and weigh the placenta (Table 35.2). Measure the disc diameter. Systematically describe all parts (Figure 35.14).

Figure 35.14 Placental examination. Adequate sampling for histologic study includes membrane roll, cross section of cord, and full thickness placental parenchyma, specifically cut to display fetal and maternal surfaces.1

• Fetal surface. Describe the color, surface characteristics (smooth, roughened, opaque, etc.), vascularity. Note the margins. Are the membranes inserted in the usual manner? Is there thickening, circummarginate or circumvallate insertion, etc.? If present, estimate the percentage of circumference affected.

• Umbilical cord. Describe insertion (central, eccentric, marginal, velamentous); measure length and cross-sectional diameter (state as average or range); state number of blood vessels. Look for varicosities, excessive coiling, false knots, true knots, edema, discoloration, thrombosis, hemorrhage, etc.

• Membranes. The amnion is the layer adjacent to the fetus. Usually the chorion and amnion are loosely fused (easily separated), but may be completely separate. Look for thickening, opacity, and adherent blood clot. Describe color, clarity, edema, etc. Make a membrane roll to include the area of rupture. There are several methods of membrane rolling, of which one is to:

1. Cut a 10 cm long strip to include both chorion and amnion extending from the edge that was attached to the placenta to the edge where the rupture occurred.

2. Grasp the placental edge with non-toothed forceps and roll the membranes around the forceps with the amnion (which is smoother) on the outside of the roll.

3. Relax the grip on the forceps slightly and use the blunt side of a knife blade to remove the roll from the forceps.

4. Pin the membrane roll onto cork and cut sections with a sharp blade, or fix the membrane roll overnight and cut sections the next day.

• Maternal surface. Is the surface intact or disrupted? If disrupted, estimate whether all tissue is present. Record and describe any subchorionic fibrin, calcification, or blood clot. Describe well-defined depressions. Give the average thickness of the placental disc. Describe any succenturiate (accessory) lobes. Cross section the specimen and look for and describe lesions, infarcts, blood clots, masses, etc. For any abnormality identified, estimate the percentage of the area involved.

• Tissue sections. It is our preference to submit at least three sections for microscopic examination: (1) cross section of the umbilical cord; (2) membrane roll; and (3) cross section of full thickness normal parenchyma somewhere centrally. Other sections should be taken as appropriate.

Twin Placenta

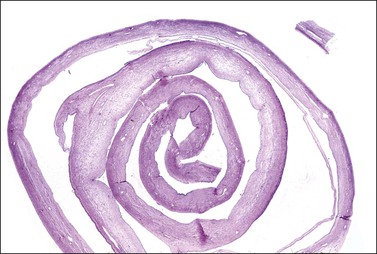

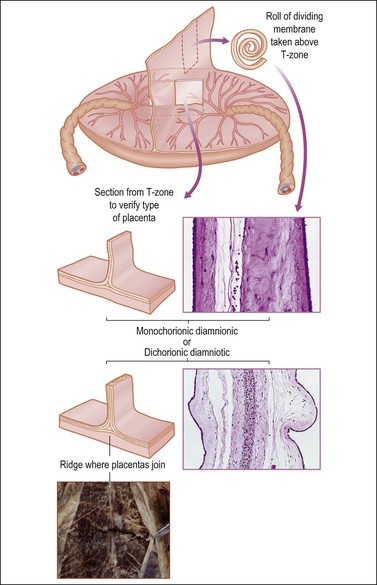

Determine the type of twin placenta, i.e., dichorionic diamniotic, monochorionic diamniotic, and monochorionic monoamniotic. Unless it is a monochorionic monoamniotic placenta, take a strip of the dividing membranes, roll it, fix, and then section (Figure 35.15). Sections of membrane away from the dividing membranes should also be rolled, fixed, and submitted. Examine, weigh, and cut the placenta (or placentas if not fused) as for a singleton placenta. If the placentas are fused, estimate the percentage each placenta constitutes of the total area, and note any differences in color between each placenta.

References

1. Lester, SC. Manual of surgical pathology, 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2010.

2. Schmidt, WA. Principles and techniques of surgical pathology. Menlo Park: Addison-Wesley; 1983.

3. Westra, WH, Hruban, RH, Phelps, TH, Isacson, C. Surgical pathology dissection: an illustrated guide. New York: Springer; 2003.

4. Greene, LA, Branton, P, Montag, A, et al. Protocol for the examination of specimens from patients with carcinoma of the vulva. http://www.cap.org/apps/docs/committees/cancer/cancer_protocols/2012/Vulva_12protocol_3101.pdf, 2012. [>/;].

5. Black, D, Tornos, C, Soslow, RA, et al. The outcomes of patients with positive margins after excision for intraepithelial Paget’s disease of the vulva. Gynecol Oncol. 2007; 104:547–550.

6. Kalof, AN, Dadmanesh, F, Longacre, TA, et al. Protocol for the examination of specimens from patients with carcinoma of the uterine cervix. http://www.cap.org/apps/docs/committees/cancer/cancer_protocols/2012/Cervix_12protocol.pdf, 2012.

7. Movahedi-Lankarani, S, Gilks, CB, Soslow, R, et al. Protocol for the examination of specimens from patients with carcinoma of the endometrium. http://www.cap.org/apps/docs/committees/cancer/cancer_protocols/2012/Endometrium_12protocol.pdf, 2012.

8. Lutman, CV, Havrilesky, LJ, Cragun, JM, et al. Pelvic lymph node count is an important prognostic variable for FIGO stage I and II endometrial carcinoma with high-risk histology. Gynecol Oncol. 2006; 102:92–97.

9. Crum, CP, Drapkin, R, Miron, A, et al. The distal fallopian tube: a new model for pelvic serous carcinogenesis. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2007; 19:5.

10. Oliva, E, Branton, PA, Scully, RE. Protocol for the examination of specimens from patients with carcinoma of the ovary. http://www.cap.org/apps/docs/committees/cancer/cancer_protocols/2012/Ovary_12protocol.pdf, 2012.

11. Kraus, FT. Introduction: the importance of timely and complete placental and autopsy reports. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2007; 24:1–4.

12. Curtin, WM, Krauss, S, Metlay, LA, Katzman, PJ. Pathologic examination of the placenta and observed practice. Obstet Gynecol. 2007; 109:35–41.