Chapter 8 Groin, scrotum and abdominal wall problems

8.1 Introduction

History

Groin or scrotal lumps are the most common symptoms of inguinoscrotal pathology. Pain is a variable, sometimes the sole, symptom. Severe persistent pain and local tenderness suggest ischaemia (from torsion or strangulation) or inflammation under tension. Local pain is not, however, a constant symptom of strangulation, which can be silent with few local manifestations, especially in femoral hernia.

Many patients present with a groin lump following a lifting strain at work. Risk factors for hernia, apart from manual exertion, include chronic cough and obstructive airways disease, chronic bladder neck obstruction, constipation and abdominal distension from ascites (Box 8.1). Larger hernias are usually of longer standing and may produce a confluent inguinoscrotal lump. Benign scrotal lumps are common and must be differentiated from hernias and malignancies.

Physical examination

Examination: patient standing

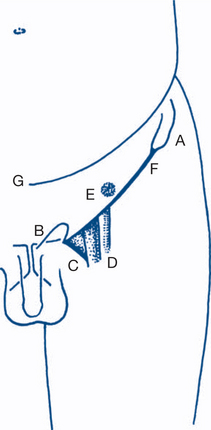

The region is inspected with the examiner sitting facing the patient, who is then asked to cough or to perform a Valsalva manoeuvre. Any lumps are noted, as are their position in relation to skin creases, bony prominences and other landmarks (Fig 8.1). Lumps are provisionally catalogued as inguinal, scrotal or inguinoscrotal. Any expansile impulse is observed and its direction noted.

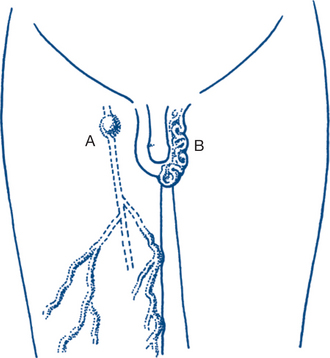

Two conditions of venous origin become immediately obvious on standing and can only be diagnosed in this position (Fig 8.2).

They should be checked first by considering the question: Is a varicocele or saphena varix present?

Varicoceles are usually easy to identify. They present as tortuous, soft, subcutaneous worm-like vascular swellings of the scrotal neck and upper scrotum that are prominent on standing, are usually left-sided and subside rapidly on lying down. They are separate from the testis and epididymis and may extend up along the cord. A venous thrill is sometimes palpable on coughing, but the soft vascular thrill is easily distinguishable from the cough impulse of an indirect inguinal hernia and is never truly expansile. It is usually also recognisable by its prominence during a Valsalva manoeuvre.

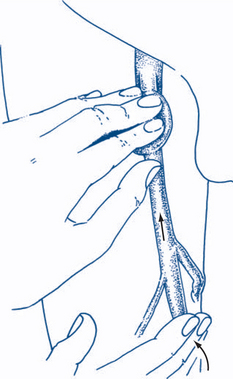

Its continuity with the long saphenous vein is additionally demonstrated by percussion over the saphenous vein in the thigh or at the knee, which transmits an impulse to a finger held over the groin lump above (Fig 8.3).

Figure 8.3 Saphena varix

Percussion over the saphenous vein in the thigh produces a transmitted impulse in the varix above.

Eight subsequent questions should be answered from inspection and palpation.

2 Is the hernia inguinal or femoral?

Differentiation is almost always possible by identifying whether the hernial sac emerges from the external inguinal ring above and medial to the pubic tubercle (inguinal hernia) or from the femoral canal and its opening into the thigh just above the saphenous vein, below and lateral to pubic tubercle (femoral hernia) (Fig 8.4).

More precisely, the external inguinal ring can be examined in males by invaginating the scrotum. This procedure is uncomfortable for the patient and must be performed gently and with consideration. If the hernia is not easily reducible while standing, this part of the examination is best reserved until the patient lies down. The examiner’s index finger of the same side as that being examined is placed at the lowest point of the scrotum and gently invaginates the scrotum upwards towards the ring. When sufficient slack has been invaginated so that the examining finger is in front of the pubis, the finger is pronated so that its pulp comes to lie over the external inguinal ring, with enough free play so that the finger can be gently moved without undue discomfort. It is then easy to palpate the pubic crest and the pubic tubercle at its lateral edge and to define precisely the superior and inferior crura of the external ring and the ring itself. Asking the patient to cough or to lift the head and shoulders from the couch tenses the margins of the ring and makes them easier to define. The superficial inguinal ring normally will not admit the index finger tip: if it is enlarged enough to admit the finger into the inguinal canal, an inguinal hernia is almost certainly present. The finding of an enlarged external ring in the absence of a lump is helpful in confirming the diagnosis when the patient’s history of hernia is unequivocal, but no lump is palpable or elicitable on examination. Usually the expansile impulse of the protruding sac when the patient coughs or strains is unmistakable and diagnosis of an inguinal hernia (or its exclusion) can be made with certainty. Separation of inguinal from femoral hernias is facilitated by contrasting an empty and normal inguinal ring with the femoral hernial sac emerging below and lateral to the finger.

Examination: patient supine

4 Is the hernia strangulated?

Strangulation (impairment of the blood supply of the hernial contents) is a serious complication requiring urgent surgery and is more likely to occur in irreducible hernias with narrow necks. Strangulation usually is attended by symptoms of persisting pain and irreducibility over the hernia. Abdominal pain, distension, vomiting and constipation due to bowel obstruction will also be present if the sac contents include the bowel. Strangulation may, however, give no local symptoms referable to the herni, hence the importance of checking hernial orifices in all patients presenting with symptoms of bowel obstruction (Ch 7.8).

6 Can one get above the scrotal lump?

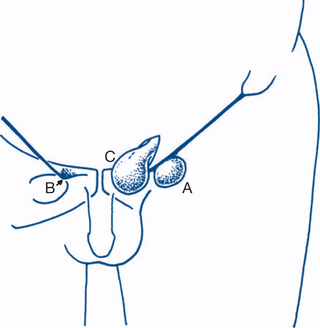

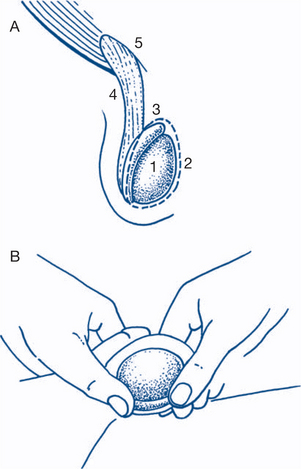

The body of the testis, the tunica vaginalis, the epididymis and the cord back to the inguinal ring are systematically examined to determine the origins of the scrotal lump (Fig 8.5).

8 Does the lump arise from the coverings or from appendages?

Lymph node swellings are common. They are usually easy to diagnose from their position and consistency and the presence of a focal lesion in the drainage area. A solitary node over the lower part of the femoral canal (gland of Cloquet) can be difficult to distinguish from an irreducible or strangulated femoral hernia. Absence of tenderness is suggestive of lymph node swelling and the draining lymph node areas should be very carefully rechecked, particularly the genitalia, toes and feet, perineum and anal canal.

8.2 Inguinoscrotal lumps

Scrotal lumps

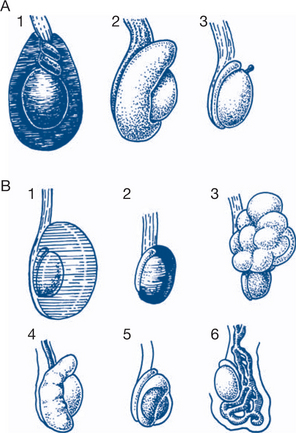

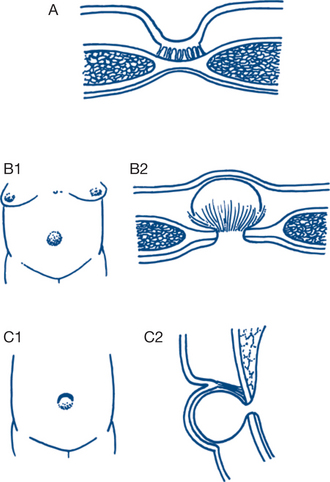

Both acute and chronic scrotal swelling have a number of causes (Fig 8.6).

Clinical assessment, diagnostic and treatment plans

Acute scrotal swelling

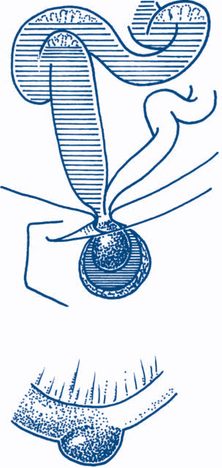

1 Torsion of testis

Presentation is an acutely swollen, painful, high-riding testis that is exquisitely tender, with a secondary hydrocele. Signs of surrounding inflammation and of systemic toxicity (fever, tachycardia) may be present. It is important to realise that this condition is a surgical emergency, that differentiation from acute epididymo-orchitis up to the age of 35 is difficult or impossible and that immediate exploration to confirm or exclude the diagnosis is the safest course. Special tests such as ultrasound or isotope scanning can enhance diagnosis but are time wasting and not specific or sensitive enough to override this important surgical principle. Delays in exploration and de-torsion will invariably increase the risk of ischaemia and necrosis. Often a history of previous episodes is present. Sometimes it is possible after analgesic premedication to reduce the torsion manually, but surgery should still proceed and aims to fix both testes operatively through a midline scrotal incision. The affected testis is first explored, untwisted and fixed (orchidopexy) by two or more sutures joining the tunica albuginea and dartos. If the testis is clearly necrotic orchidectomy is performed. The other testis, which often shows the same abnormality, must be fixed at the same time.

Chronic scrotal swellings

2 Haematocele

Acute local injury, such as a fall astride, can result in a painful acute haematocele, associated with local swelling and bruising. The main problem in such cases is to exclude urethral or testicular injury. The haematoma is usually treated conservatively, or evacuated if surgery is required for ruptured urethra or testis. If testicular injury has occurred it can often be managed conservatively; however, in major ruptures direct testicular repair may be required with or without orchidectomy.

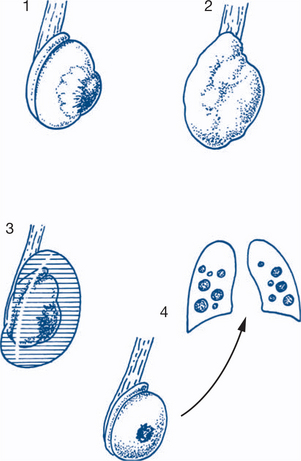

5 Testicular neoplasm

All solid lumps of the testis itself should be regarded as neoplasms until proven otherwise. Testicular neoplasms in young men are commonly germ cell tumours (90–95%, seminoma and non-seminoma) and uncommonly non-germ cell tumours (sertoli and Leydig cell tumours). In older males presenting with testicular tumours, lymphoma is by far the most common tumour, with an occasional spermatocytic seminoma. Testicular neoplasms usually present as progressive painless enlargement of the testis (Fig 8.7). There may be an accompanying clear or bloodstained secondary hydrocele — occasionally this is large and the primary tumour is occult. Metastases occur most commonly to the retroperitoneal nodes and lungs but can affect any organs including bone, liver and brain. Hormonal effects of feminisation or gynaecomastia occasionally occur. Two important local variations that can cause diagnostic difficulty are:

Important principles to apply are:

Helpful investigations in both these instances are:

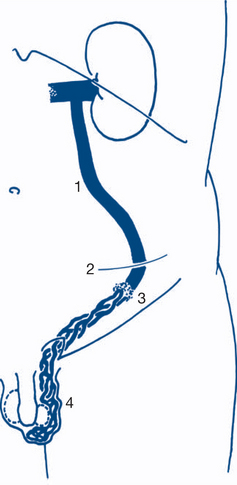

6 Varicocele

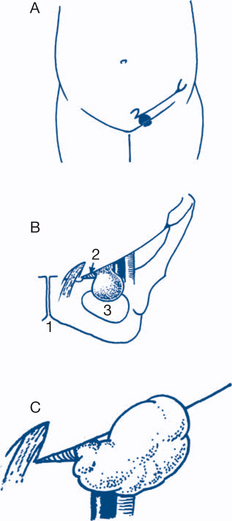

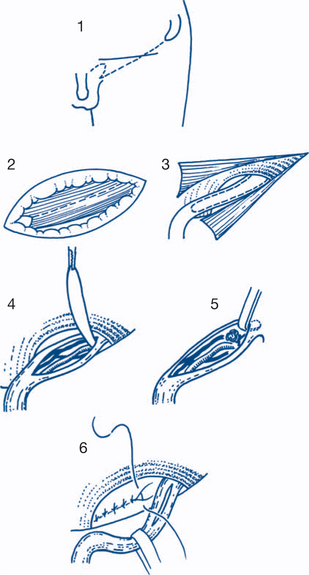

Treatment of varicocele is usually unnecessary; most patients need only reassurance. Symptomatic ones (dull discomfort, concern regarding appearance or associated infertility) are best treated by surgical ligation of the testicular veins. This is done either at the deep inguinal ring by a groin approach or in the retroperitoneum by a left-sided McBurney extraperitoneal approach and can be done laparoscopically (Fig 8.8).

Groin and inguinoscrotal lumps

Figure 8.9 depicts the common causes of inguinoscrotal lumps.

Clinical assessment and treatment plan

The differentiation of inguinal and femoral hernias is usually straightforward and has been discussed under clinical assessment (Box 8.3).

Box 8.3

Clinical features of inguinal hernia

Indirect hernia

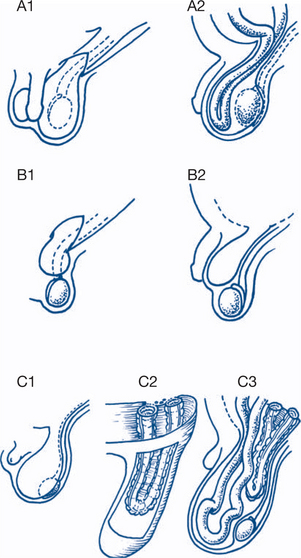

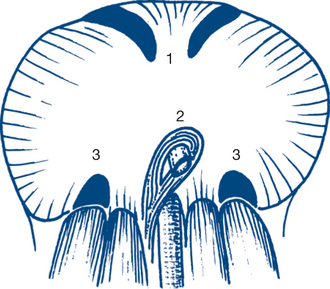

Inguinal hernias are much more common than femoral hernias and males are more commonly affected than women. Inguinal hernias may be direct or indirect (Fig 8.10).

Indirect (oblique) inguinal hernia. The peritoneal sac originates at the deep inguinal ring and is thus carried out the external ring within the spermatic cord in males. The coverings of the sac are those of the cord and comprise a component from each layer of the parietes. Large hernias follow the cord and descend into the scrotum. At operation the neck of the sac can be followed to the deep inguinal ring. Indirect hernias can enter a congenital or acquired sac. In infants and children a congenital sac is the usual pathology. In adults the oblique sac may be either acquired or congenital.

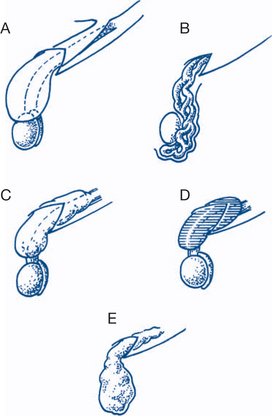

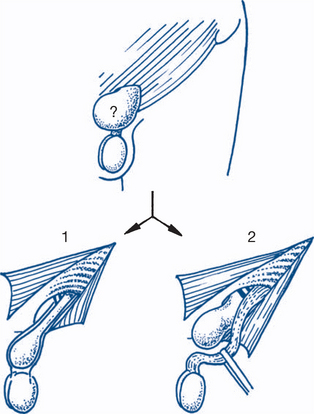

Indirect hernias are classified anatomically as shown in Figure 8.11.

Hernia magna is a condition in which the sac is in continuity with the tunica vaginalis and thus certainly congenital. The hernial contents can descend to the bottom of the scrotum alongside the testis; strangulation is a constant danger (Fig 8.12).

A variant of direct inguinal hernia is the direct funicular hernia (Ogilvie’s hernia), in which the defect is a small split in the fascia transveralis or conjoint tendon and the sac is oblique and funicular. These are more common in young patients after a strain and are subject to complications such as strangulation.

Femoral hernia. Femoral hernias are more common in women than men, but as inguinal hernias are very much more common than femoral hernias, the commoner of the two hernias in women is still the inguinal hernia. The sac of a femoral hernia has a recurved and sinuous course through the femoral ring and canal, saphenous opening and groin (Fig 8.13). Thus strangulation frequently occurs and is an ever-present danger in femoral hernias. The sac of a femoral hernia consists mainly of fat so the cough impulse is often less apparent than with inguinal hernias. A strangulated femoral hernia may present with bowel obstruction or septicaemia due to omental necrosis and yet have no overt symptoms referable to the hernia. The tense and tender groin lump is always apparent on careful examination but can be buried in folds of groin fat in the obese.

Richter’s hernia is a variant of strangulated hernia when only part of the circumference of the bowel is entrapped and is common as a complication of femoral hernia (Fig 8.14).

Interparietal (interstitial) hernias. These hernias run between planes and are more likely to occur with recurrent hernias. Recurrent hernias after repair are usually clearly inguinal or femoral but sometimes the origins of a recurrent hernia are difficult to determine except by operation. Spigelian hernia is an interparietal hernia at the lateral rectus edge.

Management plan

Surgical repair of inguinal hernias in young children can be by simple sac excision (herniotomy). In all other instances, repair should combine herniotomy with repair of the internal ring (herniorrhaphy) and of the posterior wall of the canal (hernioplasty), traditionally by some variant of the Bassini repair, with suture of conjoint tendon to inguinal ligament (Fig 8.15).

Saphena varix and lymph node swellings have already been discussed (Ch 8.1 and 8.2). Other causes of groin swellings include femoral artery aneurysm, maldescent of testis, psoas abscess, encysted hydrocele of the cord (or canal of Nuck in a female), lipomatosis of the cord and, rarely, a testicular neoplasm infiltrating the cord. Careful physical examination will separate those other causes from hernias.

8.3 Abdominal wall problems

Umbilical discharge

Clinical features and treatment plan

3 Intertrigo, umbilical concretions or granulomas

These are associated with a deep umbilical dimple or crevice and with poor hygiene.

Umbilical swellings and defects

Clinical features and treatment plan

2 Umbilical hernias

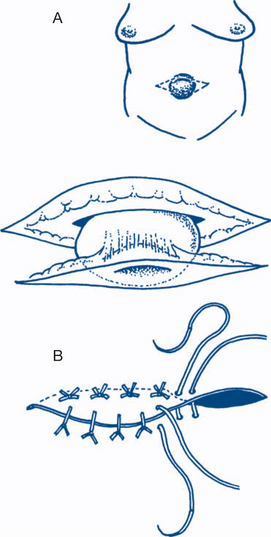

Secondary (acquired) umbilical hernias are most common in middle-aged women associated with multiparity and obesity and in patients with ascites. The defect is often just above the umbilical cicatrix and the umbilical skin scar comes to lie eccentrically on the inferior aspect of the skin lump (Fig 8.16).

These umbilical (or paraumbilical) hernias can grow to a large size and often contain omentum, small bowel and transverse colon. Complications of irreducibility and strangulation are quite common; most should be repaired as soon as possible after presentation. Mayo’s overlapping repair gives excellent results (Fig 8.17) for small umbilical hernias but larger ones are best repaired using prolene mesh in a tension- free fashion. Umbilical hernias can sometimes be the presenting sign of ascites from an intra-abdominal malignancy.

Swellings of the abdominal wall

Clinical features and treatment plan

2 Abdominal wall hernias

Hernias are focal protrusions or malpositions of the contents of a confined space or compartment.

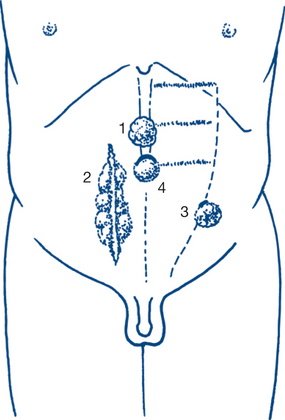

External hernias form localised protrusions through a defect in the abdominal wall. Groin hernias (inguinal, femoral) are the most common type. Other external abdominal hernias are umbilical hernia, incisional (ventral) hernia, epigastric hernia, Spigelian hernia and lumbar hernia (Fig 8.18).

Internal hernias occur through defects of the internal linings relevant to the compartment or by internal entrapment. Common internal abdominal hernias are through the oesophageal hiatus, through developmental defects via the foramina of Morgagni or Bochdalek (Fig 8.19), through the obturator or sciatic foramina, through the perineal floor or through congenital or acquired intraperitoneal recesses and foramina (e.g. foramen of Winslow). Intraperitoneal entrapments most commonly follow operations (e.g. paracolostomy hernia after excision of the rectum, postgastrectomy internal hernias and postoperative adhesions). Developmental peritoneal fossae and recesses are most common around the duodenum (superior and inferior duodenal recesses, mesentericoparietal recess of Waldeyer) and appendix and caecal areas.

Incisional hernia. Wound infection is the most common cause of incisional hernias, which are more common in vertical incisions than in transverse ones. Incisional hernias often grow progressively and are best repaired early if symptomatic and if the patient’s general status allows. Some incisional hernias can be very large and repair may require an implanted mesh prosthesis of nonabsorbable material.

Rarer forms of internal hernia include: