Chapter 497 Gonadal and Germ Cell Neoplasms

Pathogenesis

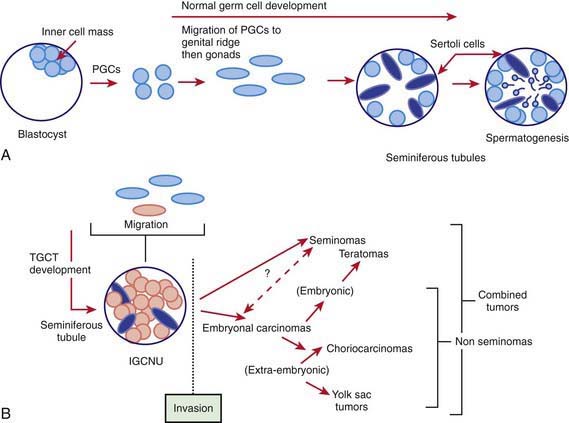

The GCTs and non-GCTs arise from primordial germ cells and coelomic epithelium, respectively. Testicular and sacrococcygeal GCTs arising during early childhood characteristically have deletions at chromosome arms 1p and 6q and gains at 1q, and lack the isochromosome 12p that is highly characteristic of malignant GCTs of adults. Testicular GCT also may demonstrate loss of imprinting. Ovarian GCTs from older girls characteristically have deletions at 1p and gains at 1q and 21. Because GCTs may contain benign and mixed malignant elements in different areas of the tumor, extensive sectioning is essential to confirm the correct diagnosis. The many histologically distinct subtypes of GCTs include teratoma (mature and immature), endodermal sinus tumor, and embryonal carcinoma (Fig. 497-1). Non-GCTs of the ovary include epithelial (serous and mucinous) and sex cord–stromal tumors; non-GCTs of the testicle include sex cord/stromal tumors (e.g., Leydig cell, Sertoli cell).

Clinical Manifestations and Diagnosis

The clinical presentation of germ cell neoplasms depends on location. Ovarian tumors often are quite large by the time they are diagnosed. Extragonadal GCTs occur in the midline, including the suprasellar region, pineal region, neck, mediastinum, and retroperitoneal and sacrococcygeal areas. Symptoms relate to mass effect, but the intracranial GCTs often present with anterior and posterior pituitary deficits (Chapter 491).

Cushing B, Giller R, Cullen JW, et al. Randomized comparison of combination chemotherapy with etoposide, bleomycin, and either high-dose or standard-dose cisplatin in children and adolescents with high risk malignant germ cell tumors: a pediatric intergroup study—Pediatric Oncology Group 9049 and Children’s Cancer Group 8882. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2691-2700.

Einhorn LH, Williams SD, Chamness A, et al. High-dose chemotherapy and stem-cell rescue for metastatic germ-cell tumors. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:340-348.

Feldman DR, Bosl GJ, Sheinfeld J, et al. Medical treatment of advanced testicular cancer. JAMA. 2008;299:672-684.

Horwich A, Shipley J, Huddart R. Testicular germ-cell cancer. Lancet. 2006;367:754-764.

Kanetsky PA, Mitra N, Vardhanabhuti S, et al. Common variation in KITLG and at 5q31.3 predisposes to testicular germ cell cancer. Nat Genet. 2010;41:811-815.

Marina N, London WB, Frazier L, et al. Prognostic factors in children with extragonadal malignant germ cell tumors: a pediatric intergroup study. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2544-2548.

Rapley EA, Turnbull C, Olama AAA, et al. A genome-wide association study of testicular germ cell tumor. Nat Genet. 2001;41:807-810.

Rogers PC, Olson TA, Cullen JW, et al. Treatment of children and adolescents with stage I testicular and stages I or II ovarian malignant germ cell tumors: a pediatric intergroup study—Pediatric Oncology Group 9048 and Children’s Cancer Group 8891. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:563-569.

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Recommendation statement—screening for testicular cancer. http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/3rduspstf/testicular/testiculrs.pdf. Accessed August 24, 2010

Young JL, Wu XC, Roffers SD, et al. Ovarian cancer in children and young adults in the United States, 1992–1997. Cancer. 2003;97:2694-2700.