Chapter 561 Goiter

561.1 Congenital Goiter

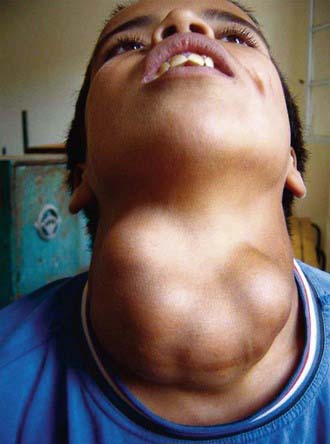

Enlargement of the thyroid at birth may occasionally be sufficient to cause respiratory distress that interferes with nursing and can even cause death. The head may be maintained in extreme hyperextension. When respiratory obstruction is severe, partial thyroidectomy rather than tracheostomy is indicated (Fig. 561-1).

Goiter is almost always present in the infant with neonatal Graves’ disease. These goiters usually are not large; the infant manifests clinical symptoms of hyperthyroidism. The mother often has a history of Graves disease, although discovery of neonatal hyperthyroidism can lead to the diagnosis of maternal Graves’ disease. Thyroid enlargement results from transplacental passage of maternal thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulin (Chapter 562.1). TSH receptor-activating mutations are also a recognized cause of congenital goiter and hyperthyroidism.

When no causative factor is identifiable, a defect in synthesis of thyroid hormone should be suspected. Neonatal screening programs find congenital hypothyroidism caused by such a defect in 1/30,000-50,000 live births. It is advisable to treat immediately with thyroid hormone and to postpone more-detailed studies for later in life. If a specific defect is suspected, genetic tests to identify a mutation may be undertaken (Chapter 559). Because these defects are transmitted by recessive genes, a precise diagnosis is helpful for genetic counseling. Monitoring subsequent pregnancies with ultrasonography can be useful in detecting fetal goiters (Chapter 90).

When the “goiter” is lobulated, asymmetric, firm, or large to an unusual degree, a teratoma within or in the vicinity of the thyroid must be considered in the differential diagnosis (Chapter 563).

Bizhanova A, Kopp P. Minireview: the sodium-iodide symporter NIS and pendrin in iodide homeostasis of the thyroid. Endocrinol. 2009;150:1084-1090.

Caron P, Moya CM, Malet D, et al. Compound heterozygous mutations in the thyroglobulin gene (1143delC and 6725G → A [R2223H]) resulting in fetal goitrous hypothyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:3546-3553.

Hashimoto H, Hashimoto K, Suehara N. Successful in utero treatment of fetal goitrous hypothyroidism: case report and review of the literature. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2006;21:360-365.

Koksal N, Akturk B, Saglan H, et al. Reference values for neonatal thyroid volumes in a moderately iodine-deficient area. J Endocrinol Invest. 2008;31:642-646.

Moreno JC, Klootwijk W, van Toor H, et al. Mutations in the iodotyrosine deiodinase gene and hypothyroidism. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1811-1818.

Remuzzi G, Garattni S. Elimination of iodine-deficiency disorders in Tibet. Lancet. 2008;371:1980-1981.

Teng W, Shan Z, Teng X, et al. Effect of iodine intake on thyroid diseases in China. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2782-2893.

Zimmernamm MB, Jooste PL, Pandav CS. Iodine-deficiency disorders. Lancet. 2008;372:1251-1262.

561.3 Endemic Goiter and Cretinism

Clinical Manifestations

If the deficiency of iodine is mild, thyroid enlargement does not become noticeable except when there is increased demand for the hormone during periods of rapid growth, as in adolescence and during pregnancy. In regions of moderate iodine deficiency, goiter observed in school children can disappear with maturity and reappear during pregnancy or lactation. Iodine-deficient goiters are more common in girls than in boys. In areas where iodine deficiency is severe, as in the hyperendemic highlands of Papua New Guinea, nearly half the population has large goiters, and endemic cretinism is common (Fig. 561-2).

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of the myxedematous syndrome leading to thyroid atrophy is more bewildering. Searches for additional environmental factors that might provoke continuing postnatal hypothyroidism have led to incrimination of selenium deficiency, goitrogenic foods, thiocyanates, and Yersinia (Table 561-1). Studies from western China suggest that thyroid autoimmunity might play a role. Children with myxedematous cretinism with thyroid atrophy, but not children with euthyroid cretinism, were found to have thyroid growth-blocking immunoglobulins of the kind found in infants with sporadic congenital hypothyroidism. Others are skeptical about any role of thyroid growth-blocking immunoglobulins to explain these findings.

| GOITROGEN | MECHANISM |

|---|---|

| FOODS | |

| Cassava, lima beans, linseed, sorghum, sweet potato | Contain cyanogenic glucosides that are metabolized to thiocyanates that compete with iodine for uptake by the thyroid |

| Cruciferous vegetables such as cabbage, kale, cauliflower, broccoli, turnips, rapeseed | Contain glucosinolates; metabolites compete with iodine for uptake by the thyroid |

| Soy, millet | Flavonoids impair thyroid peroxidase activity |

| INDUSTRIAL POLLUTANTS | |

| Perchlorate | Competitive inhibitor of the sodium-iodine symporter, decreasing iodine transport into the thyroid |

| Others (e.g., disulfides from coal processes) | Reduce thyroidal iodine uptake |

| Smoking | An important goitrogen; smoking during breast-feeding is associated with reduced iodine concentrations in breast milk; high serum concentration of thiocyanate due to smoking might compete with iodine for active transport into the secretory epithelium of the lactating breast |

| NUTRIENTS | |

| Selenium deficiency | Accumulated peroxides can damage the thyroid, and deiodinase deficiency impairs thyroid hormone synthesis |

| Iron deficiency | Reduces heme-dependent thyroperoxidase activity in the thyroid and might blunt the efficacy of iodine prophylaxis |

| Vitamin A deficiency | Increases TSH stimulation and goiter through decreased vitamin A–mediated suppression of the pituitary TSH-β gene |

TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone.

From Zimmernamm MB, Jooste PL, Pandav CS: Iodine-deficiency disorders, Lancet 372:1251–1262, 2008.

Benmiloud M, Chaouki ML, Gutekunst R, et al. Oral iodized oil for correcting iodine deficiency: optimal dosing and outcome indicator selection. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1994;79:20-24.

Boyages SC, Halpern JP, Maberly GF, et al. A comparative study of neurological and myxedematous endemic cretinism in western China. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1988;67:1262-1271.

Caldwell KL, Jones R, Hollowell JG. Urinary iodine concentration: United States National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2001-2002. Thyroid. 2005;15:692-699.

DeLange F. Iodine deficiency as a cause of brain damage. Postgrad Med J. 2001;77:217-220.

Delange F, de Benoist B, Pretell E, et al. Iodine deficiency in the world: where do we stand at the turn of the century? Thyroid. 2001;11:437-447.

Fuse Y, Saito N, Tsuchiya T, et al. Smaller thyroid gland volume with high urinary iodine excretion in Japanese schoolchildren: normative reference values in an iodine-sufficient area and comparison with the WHO/ICCIDD reference. Thyroid. 2007;17:145-155.

Maberly GF, Haxton DP, van der Haar F. Iodine deficiency: consequences and progress toward elimination. Food Nutr Bull. 2003;24(Suppl):S91-S98.

Remuzzi G, Garattini S. Elimination of iodine-deficiency disorders in Tibet. Lancet. 2008;371:1980-1981.

World Health Organization, United Nations Children’s Fund, and International Council for the Control of Iodine Deficiency Disorders. Assessment of the iodine deficiency disorders and monitoring their elimination. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001.

561.4 Acquired Goiter

Most acquired goiters are sporadic and develop from a variety of causes; patients are usually euthyroid but may be hypothyroid or hyperthyroid. The most common cause of acquired goiter is lymphocytic thyroiditis (Chapter 560). A rare cause in children is subacute thyroiditis (De Quervain disease) (Chapter 560). Other causes include excess iodide ingestion and certain drugs, including amiodarone and lithium. Intrinsic biochemical defects in the synthesis of thyroid hormone are almost always associated with goiter; milder defects occur later in childhood. The occurrence of the disorder in siblings, onset in early life, and possible association with hypothyroidism (goitrous hypothyroidism) are important clues to the diagnosis.

Simple Goiter (Colloid Goiter)

A few children with euthyroid goiters have simple goiters, a condition of unknown cause not associated with hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism and not caused by inflammation or neoplasia. The condition predominates in girls and has a peak incidence before and during the pubertal years. Histologic examination of the thyroid either is normal or reveals variable follicular size, dense colloid, and flattened epithelium. The goiter may be small or large. It is firm in half the patients and occasionally is asymmetric or nodular. Levels of TSH are normal or low, scintiscans are normal, and thyroid antibodies are absent. Differentiation from lymphocytic thyroiditis might not be possible without a biopsy, but biopsy is usually not indicated. Therapy with thyroid hormone can help prevent progression to a large multinodular goiter, although it is difficult to separate any treatment effects from the natural history, which is for the goiter to decrease in size. Patients should be reevaluated periodically, because some have antibody-negative lymphocytic thyroiditis and therefore are at risk for changes in thyroid function (Chapter 560).

Akcurin S, Turkkahraman D, Tysoe C, et al. A family with a novel TSH receptor activating germline mutation (p. Ala485Val). Eur J Pediatr. 2008;167:1231-1237.

Brix TH, Kyvik KO, Hegedus L. Major role of genes in the etiology of simple goiter in females: A population-based twin study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:3071-3075.

Daneman D, Davy T, Mancer K, et al. Association of multinodular goiter, cystic renal disease, and digital anomalies. J Pediatr. 1985;107:270-272.

De Vries L, Bulvik S, Phillip M. Chronic autoimmune thyriditis in children and adolescents: at presentation and during long-term follow-up. Arch Dis Child. 2009;94:33-37.

Feuillan PP, Shawker T, Rose SR, et al. Thyroid abnormalities in the McCune-Albright syndrome: Ultrasonography and hormonal studies. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1990;71:1596-1601.

Gopalakrishnan S, Chugh PK, Chhillar M, et al. Goitrous autoimmune thyroiditis in a pediatric population: a longitudinal study. Pediatrics. 2008;122:e670-e674.

Jaruratanasirkul S, Leethanaporn K, Suchat K. The natural clinical course of children with an initial diagnosis of simple goiter: A 5-year longitudinal follow-up. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2000;13:1109-1113.