62 Glomerulonephritis

Etiology and Pathogenesis

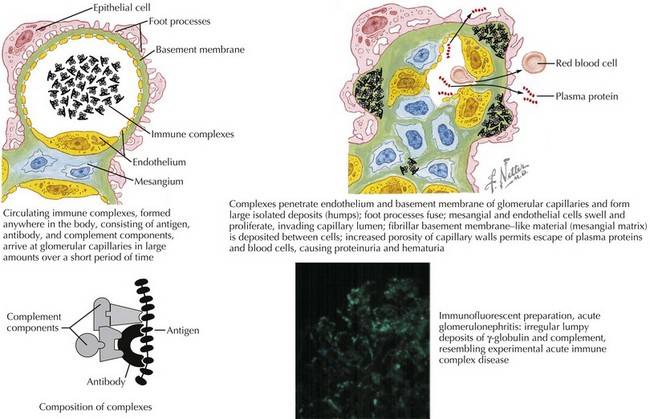

Most glomerulonephritides result from either circulating immune complex deposition within the glomerulus or in situ immune complex formation. This activates complement, as well as cellular and humoral pathways of inflammation. Within the glomerulus, there can be endothelial, epithelial, and mesangial hypercellularity, infiltration of leukocytes, thickening or duplication of the glomerular basement membrane, and necrosis (Figure 62-1). This results in loss of capillary integrity and obstruction of blood flow through the glomerular capillary loops. This capillary injury and obstruction of glomerular blood flow leads to the fluid overload, oligoanuric renal failure, hematuria, and RBC casts.

Differential Diagnosis

Acute Postinfectious Glomerulonephritis

Acute poststreptococcal GN (APSGN) is the most common cause of APIGN in children and has a higher incidence in developing countries (Figure 62-2). APSGN is caused by nephritogenic forms of Lancefield group A streptococci. In most cases, there is clinical or laboratory evidence of antecedent streptococcal infection. APSGN must be confirmed or ruled out before looking for less common causes of post infectious GN (Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus viridans).

By light microscopy, findings in APSGN include glomerular enlargement, mesangial cell expansion and proliferation, and neutrophil exudation (see Figure 62-2). Electron microscopy (EM) reveals discrete subepithelial deposits.

Henoch-Schönlein Purpura Nephritis

HSP nephritis is a small vessel vasculitis caused by IgA deposition within the glomeruli in the context of systemic HSP. Renal manifestations may present weeks after the onset of systemic HSP; rarely is it the first feature manifested in this syndrome. Prevalence of renal manifestations is subject to observer bias. Pediatric nephrology centers report that 50% of children with HSPN have hematuria and proteinuria, 8% have acute GN (AGN), 13% have nephrotic syndrome, and 29% have a mixed nephritic and nephrotic syndrome. Treatment of HSP nephritis is controversial because of a high rate of spontaneous remission and the lack of rigorous studies regarding treatment. Prognostic features are noted in Table 62-1.

Table 62-1 Poor Prognostic Features of Selected Glomerulonephritides and Recommended Treatment

| Disease | Poor Prognostic Features | First-Line Treatment |

|---|---|---|

| IgAN | Proteinuria >1 g/24 h, hypertension, azotemia, interstitial fibrosis, sclerotic glomeruli | If medical treatment,- corticosteroid ACEI |

| HSP | Presence of nephritic or nephrotic syndrome, renal failure, nephrotic-range ongoing proteinuria, interstitial fibrosis, sclerotic glomeruli | If medical treatment needed, corticosteroids, immunosuppressive agents |

| SLE | Diffuse proliferative GN (WHO Class IV), ↑ creatinine, persistent HTN, chronic anemia, nephrotic-range proteinuria | Corticosteroid therapy, cyclophosphamide, azathioprine, MMF |

| ANCA+ vasculitis or pauci-immune GN | Crescents on biopsy, frequent relapses | Corticosteroid therapy, azathioprine, MMF, cyclophosphamide |

| MPGN | Type II disease, nephrotic-range proteinuria | Corticosteroid therapy |

ANCA, antineutrophilic cytoplasmic antibody; AZA, azathioprine; CCS, corticosteroids; GN, glomerulonephritis; HSP, Henoch-Schönlein purpura; HTN, hypertension; IgAN, IgA nephropathy; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; MPGN, membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; WHO, World Health Organization.

Evaluation

Other Symptoms and Review of Systems

Physical Examination

Other Physical Examination Findings

Physical examination findings that may indicate specific etiologies of AGN are detailed in Table 62-2.

Table 62-2 Types of Glomerulonephritis with Possible Associated Physical Examination Findings

| Disease | Notable Physical Examination Findings |

|---|---|

| ASPGN | Pharyngitis, healing or healed impetigo or ecthyma |

| IgAN | Coryza, congestion, pharyngitis, cough |

| HSP | Abdominal pain, palpable purpura |

| SLE | Malar or discoid rash, painless oral ulcers, neurologic changes, arthritis, serositis |

| ANCA positive: pauci-immune GN | Weight loss, fever, myalgias, sinusitis, hemoptysis (pulmonary–renal syndrome) |

| HUS: Shiga toxin positive Pneumococcal |

Bloody diarrhea Lobar pneumonia |

ANCA, antineutrophilic cytoplasmic antibody; APSGN, acute poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis; HSP, Henoch-Schönlein purpura; HUS, hemolytic-uremic syndrome; IgAN, IgA nephropathy; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus.

Laboratory Evaluation

Laboratory evaluation is required to assess renal function and serum electrolyte concentrations, evaluate for the presence of GN, and determine the etiology of the glomerular inflammation. The presence of RBC casts should be determined in a fresh urine specimen examined by microscopy. The serum C3 concentration helps differentiate among the many causes of GN. A low serum C3 concentration is present in APSGN and MPGN. Patients with SLE may have low serum concentrations of C3 and C4. In those with IgAN, SVV, HUS, Alport syndrome, and HSP nephritis, the serum C3 concentration is normal. The serum C3 concentration should return to normal in 6 to 8 weeks in children with APSGN. If this does not occur and the patient remains symptomatic, then a biopsy should be considered to evaluate for MPGN. Studies used to differentiate among the glomerulonephritides are detailed in Table 62-3.

Table 62-3 Laboratory Tests Important in Distinguishing Etiology of Glomerulonephritis

| Disease | Laboratory Evaluation |

|---|---|

| APSGN | C3, ASOT, Streptozyme, rapid strep or throat culture |

| IgAN | Glycosylated IgA1, renal biopsy |

| SLE | C3, C4, ANA, anti-Smith, anti dsDNA, and renal biopsy |

| ANCA+ Vasculitis/Pauci-Immune glomerulonephritis | ANCA titers, anti-PR3 Ab, anti-MPO Ab, and renal biopsy |

| HUS | Stool culture for Escherichia coli O157, stool Shiga toxin |

| MPGN | C3, C4, hepatitis panel (secondary causes of MPGN) |

| Alport’s syndrome | Genetic test for mutations in type IV collagen gene COL4A5 and renal biopsy |

ANCA, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody; ANA, antinuclear antibodies; APSGN, acute poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis; ASOT, antistreptolysin titer; C3/4, complement 3/4; HSP, Henoch-Schönlein purpura; HUS, hemolytic-uremic syndrome; IgAN, IgA nephropathy; MPGN, membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis; PR3, serine protease 3; MPO, myeloperoxidase; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus.

Management

Therapies Targeting the Underlying Glomerulonephritis

The therapies described in this chapter are nonspecific and treat the homeostatic derangements directly attributable to the GN. Strategies in use that target the underlying glomerular inflammation include corticosteroids, cyclophosphamide, and plasmapheresis. Table 62-1 lists prognostic features for the different types of GN along with suggestions for first-line treatment.

Kaplan BS, Meyers KEC. Pediatric Nephrology and Urology; The Requisites in Pediatrics, ed 1. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2004.

National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents. The Fourth Report on the Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents. Pediatrics. 2004;114:555-576.