82 Genitourinary Trauma

• Evaluate suspected genitourinary tract injuries in retrograde fashion; check for urethral disruption before bladder rupture and bladder rupture before ureteral or kidney injury.

• Suspect urethral injury in blunt trauma patients with a significant pelvic fracture, blood at the urethral meatus, gross hematuria, absent or abnormally positioned prostate on digital rectal examination, and ecchymosis or hematoma involving the penis, scrotum, or perineum.

• Evaluate urethral integrity by retrograde urethrography when urethral injury is suspected and a urinary catheter cannot easily be placed with a single gentle attempt.

• Suspect bladder rupture in blunt trauma patients with pelvic trauma and gross hematuria and in those sustaining a significant pelvic fracture.

• Suspect upper tract (kidney or ureter) injury in blunt trauma patients with gross hematuria or with microscopic hematuria when the patient has sustained a significant decelerating mechanism or exhibits hypotension.

• Suspect genitourinary involvement when any penetrating injury is inflicted in proximity to the genitourinary system.

Pathophysiology

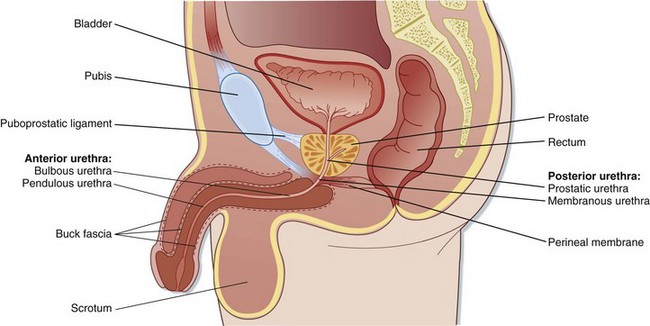

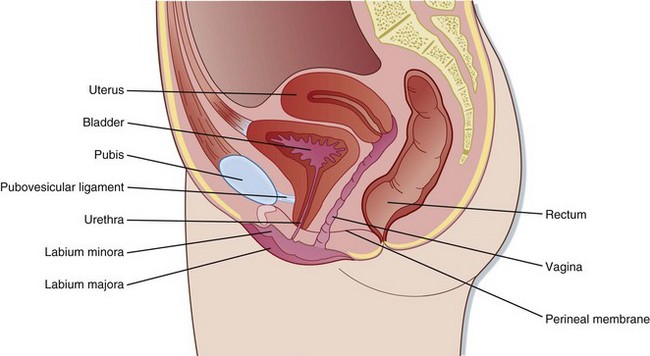

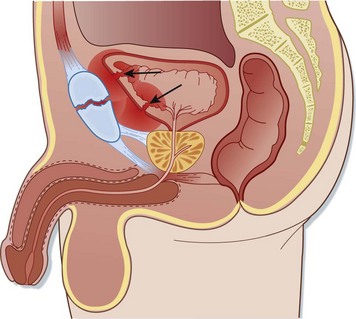

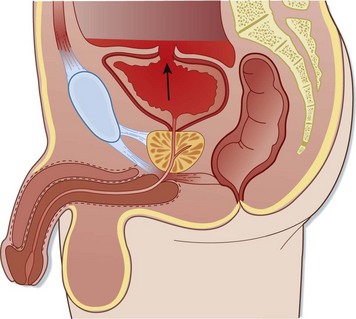

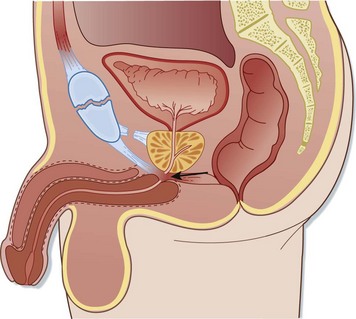

Anatomically, the genitourinary system is divided into lower and upper tracts. This division is clinically important because specific mechanisms tend to injure different parts of the genitourinary system. The lower genitourinary tract consists of the external genitalia, urethra, and bladder (Figs. 82.1 and 82.2). The upper genitourinary tract consists of the ureters and kidneys.

Urethra

The male urethra is divided into anterior (bulbous and pendulous) and posterior (prostatic and membranous) portions. Traditionally, this division has been described at the level of the urogenital diaphragm; however, recent work has questioned the existence of this structure, as classically taught.1–3 Regardless, the weakest point of the posterior urethra is the bulbomembranous junction, and it is the area where the majority of posterior urethral disruptions occur.1

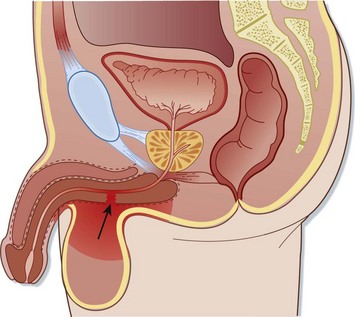

Injuries to the anterior urethra occur from direct blows, straddle injuries, or instrumentation or in conjunction with a penile fracture (Fig. 82.3). By contrast, posterior urethral injuries usually occur in the setting of significant pelvic fractures, often caused by motor vehicle collisions (Fig. 82.4). Penetrating injuries may be inflicted by gunshot wounds, knives, or other sharp objects. Urethral injuries are much less common in women because the female urethra is short and relatively mobile and lacks significant attachment to the pubis.

Fig. 82.4 Posterior urethral injury.

Note the displacement of the prostate by the hematoma at the site of injury (arrow).

Overall, urethral disruption accompanies pelvic fracture in approximately 5% of cases in women and up to 25% of cases in men.1,4 However, the risk for urethral injury varies with the type of pelvic fracture. High-risk fractures include concomitant fractures of all four pubic rami (straddle fractures; Fig. 82.5) or fractures of both ipsilateral rami accompanied by massive posterior disruption through the sacrum, sacroiliac joint, or ilium. Low-risk injuries include single ramus fractures and ipsilateral ramus fractures without disruption of the posterior ring. The risk for urethral injury approaches zero with isolated fractures of the acetabulum, ilium, and sacrum.1 Posterior urethral disruption occurs when a significant pelvic fracture causes upward displacement of the bladder and prostate. Avulsion of the puboprostatic ligament is followed by stretching of the membranous urethra and subsequent partial or complete disruption at the anatomic weak point, the bulbomembranous junction.1

Ureters

Ureteral injury is rare and occurs in less than 1% of all genitourinary injuries.5 In adults, penetrating injuries account for approximately 90% of cases, most commonly inflicted by gunshot wounds.6 In children, the most common mechanism is blunt avulsion at the ureteropelvic junction as a result of a motor vehicle collision or a fall from a height. This injury pattern is thought to be due to the increased mobility of the pediatric vertebral column, which allows extreme hyperextension that results in upward displacement of the kidney and separates it from the relatively immobile ureter.

Kidneys

Significant force is required to injure the kidney. Motor vehicle collisions, falls, direct blows, and lower rib fractures are common mechanisms. Significant decelerating force may cause avulsion of the renal pedicle. In children, bicycle accidents represent a prominent mechanism of renal injury.7 Penetrating injuries may be inflicted by gunshot wounds, knives, or other sharp objects.

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

External Genitalia Injuries

Penile fracture is often accompanied by an audible snapping sound and is followed immediately by severe pain, detumescence, swelling, and ecchymosis. The corpus spongiosum is involved in 20% to 30% of cases, and urethral injury occurs in 10% to 20%. If the Buck fascia remains intact, the swelling and ecchymosis are confined to the penile shaft. If not, blood and urine may dissect into the scrotum, perineum, and suprapubic spaces.8,9

In patients with penetrating mechanisms, a careful and complete physical examination should be conducted to search for associated or additional occult injuries. In one series, gunshot wounds involving the penis were associated with injury to other organ structures in 80% of cases.10 Violation of the corpora cavernosa requires operative intervention and is heralded by an expanding penile hematoma, significant bleeding from a wound to the penile shaft, or a palpable corporal defect.

Injuries to the female genitalia are often associated with pelvic fractures. Important mechanisms include physical or sexual assault, consensual intercourse, and penetrating injuries. In the presence of a pelvic fracture or blood at the introitus, meticulous vaginal examination is mandated. Complications of missed vaginal injuries include infection, fistula formation, and significant hemorrhage.11,12 In one series, 25% of women sustaining injury to the external genitalia required red blood cell transfusion because of blood loss from the genital injury alone.11

Ureteral Injuries

Hematuria (gross or microscopic) is not a reliable predictor of ureteral injury because the findings on urinalysis are normal approximately 25% of the time.7,13 The diagnosis is frequently missed on the initial evaluation because the signs and symptoms are minimal and nonspecific. Delayed findings include fever, flank pain, and a palpable flank mass (urinoma). Ureteral injury should be considered in patients with any penetrating injury that has a trajectory in proximity to the ureter.

Digital Rectal Examination

Classic teaching has held that digital rectal examination provides useful clinical information in the evaluation of a blunt trauma patient who has sustained a pelvic fracture or in whom a urethral injury is suspected. The technique described includes evaluation for an absent or high-riding prostate, the presence of which may be associated with posterior urethral disruption and the need for prompt investigation for urethral integrity. However, multiple studies have now demonstrated a relative lack of utility of digital rectal examination for the detection of urethral injuries.14–16 Accordingly, the decision to evaluate for urethral injury should not rely solely on the findings of digital rectal examination but instead should consider additional clinical features, including the mechanism of injury, physical examination findings such as a scrotal or perineal hematoma or blood at the urethral meatus, and the presence and type of any associated pelvic fracture.

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

External Genitalia

Ultrasonography is used to evaluate testicular blood flow in cases of suspected torsion and to supplement the physical examination in cases of testicular trauma. However, this modality has only modest sensitivity and specificity in detecting testicular rupture and is quite operator dependent.9,17

Urethra

After the initial history and physical examination, an anteroposterior (AP) pelvic radiograph should be obtained to assess for fracture. In cases of suspected urethral injury, classic teaching has held that it is imperative to evaluate the integrity of the urethra with a retrograde urethrogram before attempting to place a urinary catheter to avoid worsening a partial urethral disruption. Although the literature on this topic is sparse, one small retrospective review of 13 cases of urethral injury demonstrated no evidence that a blind attempt to insert a urinary catheter worsened the initial injury.18 Consequently, in the presence of gross hematuria without other signs of urethral injury, it is reasonable to make one attempt at passing a Foley catheter. If resistance is encountered, the attempt should be aborted and urethral integrity evaluated by retrograde urethrography. This procedure should be deferred if pelvic angiography is indicated because extravasation of contrast material from a urethral injury may obscure computed tomography (CT) and angiography images and complicate attempts to control significant pelvic hemorrhage by vascular embolization.19

Retrograde Urethrography Procedure

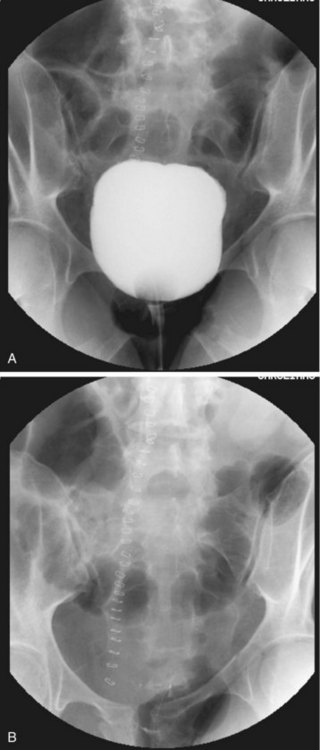

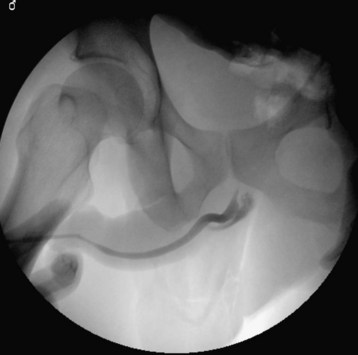

Alternatively, a Foley catheter can be inserted a few centimeters into the urethra and the balloon inflated to ensure a snug fit within the fossa navicularis; next, attach a catheter-tip syringe filled with contrast material as described previously. Inject 50 to 60 mL (0.6 mL/kg in children) of contrast agent and obtain a KUB radiograph simultaneously with infusion of the final 10 mL. Lack of urethral extravasation with filling of the bladder indicates a normal study. Partial disruption is indicated by urethral extravasation accompanied by partial filling of the bladder. Complete disruption results in urethral extravasation with no filling of the bladder (Fig. 82.6).

Fig. 82.6 Retrograde urethrogram showing complete urethral rupture at the level of the membranous urethra.

If urethral injury is suspected, obtain a retrograde urethrogram first to ensure urethral integrity before placement of a Foley catheter. Once urethral injury is excluded and a Foley catheter has been placed, evaluate for bladder rupture in all patients with gross hematuria and in those who have sustained a significant pelvic fracture. This is accomplished by retrograde cystography or retrograde CT cystography. Additional relative indications for bladder imaging include gross hematuria without pelvic fracture and microscopic hematuria with pelvic fracture.20

Retrograde Cystography Procedure

The most common reason for false-negative cystographic results is failure to instill enough contrast material. Once the bladder is filled, clamp the catheter and obtain a KUB radiograph (Fig. 82.7). After ensuring adequacy of the contrast film, unclamp the catheter, allow the bladder to drain, and obtain a postevacuation film. Extraperitoneal rupture appears as a flamelike area of contrast material confined to the pelvis, often extending lateral to the bladder (Fig. 82.8). In cases of intraperitoneal rupture, contrast material outlines the bowel and other structures in the peritoneal cavity (Fig. 82.9). Using the baseline film for comparison, carefully scrutinize the postevacuation film for any subtle areas of extravasation not seen on the contrast-distended view.

For retrograde CT cystography, the bladder is filled in an identical manner. Do not simply clamp the Foley catheter and rely on passive filling of the bladder by intravenously administered contrast material for CT cystography. Multiple studies have demonstrated missed injuries with this approach.21–24 A postevacuation film is not necessary with retrograde CT cystography.

Ureter

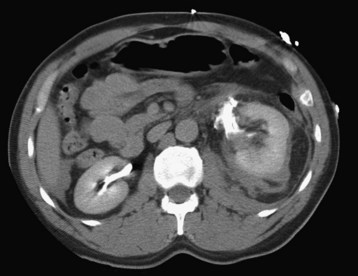

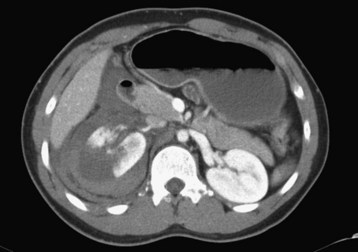

The diagnosis of ureteral injury is elusive. Intravenous pyelography has long been the test of choice, although its reported sensitivity is highly variable.6,13,25 CT imaging has gained popularity of late and is often indicated for identification of related injuries. In cases of suspected ureteral or renal pelvis disruption, additional delayed CT images (obtained 10 minutes after injection of contrast agent) are indicated to allow time for the intravenous contrast material to be excreted by the kidneys (Fig. 82.10). If operative exploration is indicated, the ureters may be directly evaluated in the surgical suite. When the diagnosis remains in doubt, retrograde pyelography may be useful.

Kidney

Renal imaging is indicated in all patients with penetrating trauma proximate to the kidneys and in those with blunt injuries and gross hematuria or microscopic hematuria with shock (defined as systolic blood pressure lower than 90 mm Hg). Additional relative indications include a significant decelerating mechanism, such as a high-speed motor vehicle collision or a fall from a height.26,27 The imaging study of choice is CT scanning with intravenous contrast enhancement. If injury to the collecting system is suspected, additional cuts should be obtained 10 minutes after injection of the contrast agent. Intravenous pyelography has been used extensively in the past but has largely been supplanted by CT.

In an unstable patient requiring immediate laparotomy, a “one-shot” intravenous pyelogram obtained in the operating room has some utility. Although this limited study does not provide sufficient sensitivity to exclude all clinically important renal injuries, it will demonstrate major renal disruption and confirm the presence of a functioning contralateral kidney. This study is accomplished by obtaining a KUB radiograph 10 minutes after rapid intravenous bolus injection of contrast material (2 mL/kg).27,28 Angiography performed on an emergency basis can be both diagnostic and therapeutic, but it is time-consuming and impractical in many centers. Ultrasonography lacks sensitivity in visualizing renal trauma and should not be relied on to exclude significant injury.

![]() Documentation

Documentation

Note the presence or absence of any abnormalities that suggest genitourinary injury. In blunt trauma patients, such abnormalities include the following:

In patients with penetrating trauma, note whether the injury trajectory occurs in proximity to the genitourinary tract.

Document the presence or absence of hematuria in the initial urine specimen.

![]() Priority Actions

Priority Actions

Because genitourinary injuries are rarely life-threatening, initial assessment of a multiply injured patient is focused on rapid identification of potentially life-threatening injuries with prompt intervention to preserve life.

During the initial resuscitation, note any findings, such as gross hematuria or an unstable pelvic fracture, that may herald genitourinary injury so that the appropriate investigation may be undertaken once the patient has been stabilized.

Treatment

External Genitalia Injuries

Traumatic testicular torsion and displacement are treated surgically. All but the most superficial penetrating injuries to the external genitalia require operative exploration, especially those that violate the corpora cavernosa. Prompt surgical exploration plus repair of penile fractures minimizes the late complications of penile curvature, erectile dysfunction, and dyspareunia.8,9 Likewise, in patients with testicular rupture, early operative intervention maximizes the rate of testicular salvage.9 Reimplantation of an amputated penis should be performed as expeditiously as possible but has been successful after 16 hours of cold ischemia.17 The majority of women with vaginal injuries will require operative repair or washout to prevent significant morbidity and mortality.11

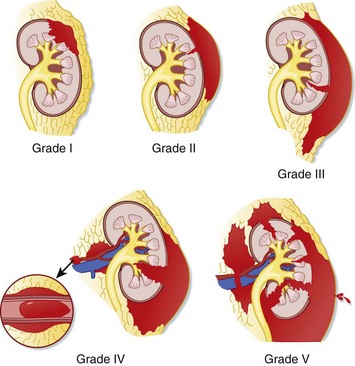

Kidney Injuries

The need for operative intervention correlates with the severity of injury as classified by the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma organ injury severity scale for the kidney (Fig. 82.11 and Table 82.1). Most grade I and II injuries can be managed nonoperatively, and nearly all grade V injuries (Fig. 82.12) require nephrectomy, which may be lifesaving in the rare case of exsanguinating hemorrhage from a renal vascular injury. Delayed nephrectomy may be indicated in the small subset of patients in whom hypertension or symptomatic renal infarction develops.27

| GRADE† | TYPE | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|---|

| I | Contusion | Microscopic gross hematuria, urologic studies normal |

| Hematoma | Subcapsular, nonexpanding hematoma without parenchymal laceration | |

| II | Hematoma | Nonexpanding perirenal hematoma confined to the renal retroperitoneum |

| Laceration | <1-cm parenchymal depth of the renal cortex without urinary extravasation | |

| III | Laceration | >1-cm parenchymal depth of the renal cortex without collecting system rupture or urinary extravasation |

| IV | Laceration | Parenchymal laceration extending through the renal cortex, medulla, and collecting system |

| Vascular | Main renal artery or vein injury with contained hemorrhage | |

| V | Laceration | Completely shattered kidney |

| Vascular | Avulsion of the renal hilum with devascularization of the kidney |

AAST, American Association for the Surgery of Trauma.

Pediatric Considerations

It is somewhat controversial whether the criteria used to determine the need for renal imaging after blunt trauma in adults may be applied to children. One issue is whether the presence of microscopic hematuria in children warrants imaging even in the absence of shock. Some authors have recommended imaging in children when urine microscopy reveals more than 50 RBCs/HPF.29,30

Certainly, the criterion of shock as defined by a systolic blood pressure lower than 90 mm Hg is unhelpful in the pediatric population. Even age-specific definitions of hypotension are of little utility because children manifest shock differently than do adults. A recent study reviewing 720 consecutive pediatric patients with suspected renal trauma concluded that using the criteria of gross hematuria, shock, and significant deceleration injury can identify all cases of renal injury.31 However, like the definition of shock, “significant deceleration injury” was not well defined in this study.

For now, consensus guidelines recommend that hemodynamically stable children with blunt trauma undergo imaging if they have gross hematuria (i.e., more than 50 RBCs/HPF) on urine microscopy.31 All children with penetrating trauma in proximity to the kidneys warrant imaging.

Follow-Up, Next Steps in Care, and Patient Education

![]() Facts and Formulas

Facts and Formulas

Pediatric Contrast Agent Dosage

The pediatric dose of a contrast agent for a retrograde urethrogram is 0.6 mL/kg to a maximum of 60 mL.

In patients younger than 11 years, calculate the appropriate amount of contrast agent in milliliters for retrograde cystography by using the formula (age in years + 2) × 30 to a maximum of 400 mL.

Tips and Tricks

If a urethral injury is suspected subsequent to successful placement of a Foley catheter, a retrograde urethrogram may be obtained by injecting the contrast agent through a small feeding tube inserted alongside the catheter.

Cautions for the emergency physician:

Ball CG, Jafri M, Kirkpatrick AW, et al. Traumatic urethral injuries: does the digital rectal examination really help us? Injury. 2009;40:984–986.

Netto FACS, Hamilton P, Kodama R, et al. Retrograde urethrocystography impairs computed tomography diagnosis of pelvic arterial hemorrhage in the presence of a lower urologic tract injury. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206:322–327.

Santucci RA, Langenburg SE, Zachareas MJ. Traumatic hematuria in children can be evaluated as in adults. J Urol. 2004;171:822–825.

Santucci RA, Wessells H, Bartsch G, et al. Evaluation and management of renal injuries: consensus statement of the renal trauma subcommittee. BJU Int. 2004;93:937–954.

Shlamovitz GZ, McCullough L. Blind urethral catheterization in trauma patients suffering from lower urinary tract injuries. J Trauma. 2007;62:330–335.

1 Koraitim MM. Pelvic fracture urethral injuries: the unresolved controversy. J Urol. 1999;161:1433–1441.

2 Andrich DE, Mundy AR. The nature of urethral injury in cases of pelvic fracture urethral trauma. J Urol. 2001;165:1492–1495.

3 Dorschner W, Biesold M, Schmidt F, et al. The dispute about the external sphincter and the urogenital diaphragm. J Urol. 1999;162:1942–1945.

4 Chapple CR, Png D. Contemporary management of urethral trauma and the post-traumatic stricture. Curr Opin Urol. 1999;9:253–260.

5 Siram SM, Gerald SZ, Greene WR, et al. Ureteral trauma: patterns and mechanisms of injury of an uncommon condition. Am J Surg. 2010;199:566–570.

6 Elliott SP, McAninch JW. Ureteral injuries from external violence: the 25-year experience at San Francisco General Hospital. J Urol. 2003;170:1213–1216.

7 Gerstenbluth RE, Spirnak JP, Elder JS. Sports participation and high grade renal injuries in children. J Urol. 2002;168:2575–2578.

8 Gottenger EE, Wagner JR. Penile fracture with complete urethral disruption. J Trauma. 2000;49:339–341.

9 Morey AF, Metro MJ, Carney KJ, et al. Consensus on genitourinary trauma: external genitalia. BJU Int. 2004;94:507–515.

10 Hall SJ, Wagner JR, Edelstein RA, et al. Management of gunshot injuries to the penis and anterior urethra. J Trauma. 1995;38:439–443.

11 Goldman HB, Idom CB, Jr., Dmochowski RR. Traumatic injuries of the female external genitalia and their association with urological injuries. J Urol. 1998;159:956–959. [erratum appears in J Urol 1998;159:1650]

12 Lev RY, Mor Y, Golomb J, et al. Missed female urethral injury complicated by myonecrosis of the thigh. J Urol. 2001;165:1216.

13 Carver BS, Bozeman CB, Venable DD. Ureteral injury due to penetrating trauma. South Med J. 2004;97:462–464.

14 Shlamovitz GZ, Mower WR, Bergmen J, et al. Poor test characteristics for the digital rectal examination in trauma patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;50:25–33.

15 Esposito TJ, Ingraham A, Luchette FA, et al. Reasons to omit digital rectal exam in trauma patients: no finger, no rectum, no useful additional information. J Trauma. 2005;59:1314–1319.

16 Ball CG, Jafri M, Kirkpatrick AW, et al. Traumatic urethral injuries: does the digital rectal examination really help us? Injury. 2009;40:984–986.

17 Bandi G, Santucci RA. Controversies in the management of male external genitourinary trauma. J Trauma. 2004;56:1362–1370.

18 Shlamovitz GZ, McCullough L. Blind urethral catheterization in trauma patients suffering from lower urinary tract injuries. J Trauma. 2007;62:330–335.

19 Netto FACS, Hamilton P, Kodama R, et al. Retrograde urethrocystography impairs computed tomography diagnosis of pelvic arterial hemorrhage in the presence of a lower urologic tract injury. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206:322–327.

20 Morey AF, Iverson AJ, Swan A, et al. Bladder rupture after blunt trauma: guidelines for diagnostic imaging. J Trauma. 2001;51:683–686.

21 Gomez RG, Ceballos L, Coburn M, et al. Consensus statement on bladder injuries. BJU Int. 2004;94:27–32.

22 Hsieh CH, Chen RJ, Fang JF, et al. Diagnosis and management of bladder injury by trauma surgeons. Am J Surg. 2002;184:143–147.

23 Haas CA, Brown SL, Spirnak JP. Limitations of routine spiral computerized tomography in the evaluation of bladder trauma. J Urol. 1999;162:51–52.

24 Vaccaro JP, Brody JM. CT cystography in the evaluation of major bladder trauma. Radiographics. 2000;20:1373–1381.

25 Perez-Brayfield MR, Keane TE, Krishnan A, et al. Gunshot wounds to the ureter: a 40-year experience at Grady Memorial Hospital. J Urol. 2001;166:119–121.

26 Mee SL, McAninch JW, Robinson AL, et al. Radiographic assessment of renal trauma: a 10-year prospective study of patient selection. J Urol. 1989;141:1095–1098.

27 Santucci RA, Wessells H, Bartsch G, et al. Evaluation and management of renal injuries: consensus statement of the renal trauma subcommittee. BJU Int. 2004;93:937–954.

28 Morey AF, McAninch JW, Tiller BK, et al. Single shot intraoperative excretory urography for the immediate evaluation of renal trauma. J Urol. 1999;161:1088–1092.

29 Morey AF, Bruce JE, McAninch JW. Efficacy of radiographic imaging in pediatric blunt renal trauma. J Urol. 1996;156:2014–2018.

30 Perez-Brayfield MR, Gatti JM, Smith EA, et al. Blunt traumatic hematuria in children. Is a simplified algorithm justified? J Urol. 2002;167:2543–2546.

31 Santucci RA, Langenburg SE, Zachareas MJ. Traumatic hematuria in children can be evaluated as in adults. J Urol. 2004;171:822–825.