Genitourinary Trauma

Renal Injury

Overview: The kidney is the third most frequently injured abdominal viscus in children and accounts for 1.3% to 15% of injuries in children who suffer blunt abdominal trauma. Children are more susceptible to renal injury during blunt trauma compared with adults because of the relatively increased mobility of the pediatric kidney, less perinephric fat, and reduced protection by a more compliant chest wall. Preexisting renal abnormalities such as a horseshoe kidney (Fig. 124-1) or pelvic kidney, hydronephrosis, cystic renal disease, and tumors may increase the size or alter the location of the kidney leading to an increased susceptibility to injury.1

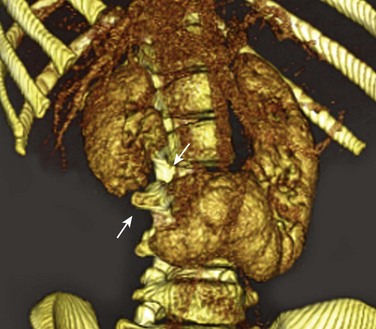

Figure 124-1 Laceration in horseshoe kidney.

Oblique three-dimensional volume reconstruction of contrast-enhanced computed tomography shows complete transection (arrows) of a horseshoe kidney.

Most children with clinically significant renal injury present with hematuria; the risk of underlying renal injury is markedly higher in patients with gross hematuria (22%) compared with those with lesser amounts of urinary blood (8%). However, the presence of asymptomatic microscopic hematuria is a low-yield sign for the presence of underlying renal injury.2

Imaging: Computed tomography (CT) is the preferred modality for initial assessment of hemodynamically stable children with suspected renal injury because of its wide availability, rapid image acquisition, and accuracy. The use of intravenous contrast material is essential for the evaluation of the kidney, and scanning during the mixed venous phase of opacification is recommended. A delayed scan may be helpful for the detection of urinary extravasation. Noncontrast scans are not generally helpful, and they unnecessarily increase radiation dose to the patient. Unstable patients who require immediate evaluation may be examined with ultrasonography at the bedside prior to complete resuscitation or surgery. Routine follow-up imaging can be performed with grey-scale and color Doppler ultrasonography in most patients, and CT can be reserved for selected patients with other associated injury or ambiguous findings on serial ultrasonography.3

The most common type of renal injury is parenchymal contusion, which manifests on CT as a focal or diffuse region of absent or delayed contrast enhancement (Fig. 124-2). The contusion is characterized by microscopic areas of hemorrhage and surrounding edema. The involved kidney may also appear larger on CT as a result of the associated edema.

Figure 124-2 Renal contusion.

A contrast-enhanced coronal computed tomography image shows markedly diminished enhancement of the upper pole of the left kidney with preservation of renal contour.

Renal collecting system injury results in urinary extravasation of intravenous contrast medium (Fig. 124-3). Urine leakage that remains encapsulated in the perirenal space is termed a urinoma. Occasionally, hemorrhage or urinary extravasation may extend into the pelvis owing to direct communication between the perirenal space in the abdomen and the prevesical extraperitoneal space in the pelvis.1

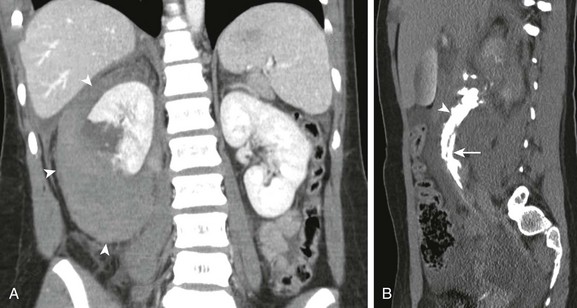

Figure 124-3 Grade IV renal laceration.

A, Coronal contrast-enhanced computed tomography shows complete transection of right kidney and large perinephric hematoma (arrowheads). B, A delayed sagittal-reformatted computed tomography scan shows extravasation of contrast-containing urine (arrowhead) along the right ureter (arrow).

The American Association for the Surgery of Trauma has developed an injury scale to categorize the increasing severity of renal injury (Table 124-1). Grade I to grade III injuries are considered low grade, and account for between 69% to 99% of all renal injuries.

Table 124-1

| Injury Grade | Renal Injury |

| I | Renal contusion, small, nonexpanding subcapsular hematoma |

| II | Superficial renal laceration not involving collecting system or deep medulla, nonexpanding perinephric hematoma |

| III | Deep renal laceration without involvement of renal collecting system, nonexpanding perinephric hematoma |

| IV | Laceration of renal collecting system, involvement of vascular pedicle |

| V | Shattered kidney, multiple lacerations, renal fragmentation |

Treatment: The great majority of renal injuries (69%–99%) are treated nonsurgically with great success. Even in high-grade injuries, no surgical intervention is necessary in 60% to 70%. Early ureteral stent placement may be considered in patients with high-grade injuries who do not demonstrate contrast material in the ipsilateral ureter.4

Bladder Injury

Overview: Blunt injuries to the bladder typically result from a blow to the lower abdomen when the bladder is distended or when the pelvis is fractured. Fortunately, the incidence of lower urinary tract injury in children is quite low, estimated at 0.2% of pediatric trauma admissions. Although approximately 50% of children with bladder tears have a pelvic fracture, only 0.5% to 3.7% of children with pelvic fractures have associated bladder injuries.5 High-yield indications for CT cystography include gross hematuria, pelvic fracture, and high-risk mechanisms of injury such as motor vehicle crashes and the presence of a seatbelt ecchymosis. Bladder injuries may be classified as intraperitoneal rupture, extraperitoneal rupture, and combined lesions.

Imaging: Standard abdominal trauma CT scanning protocols may miss important bladder injuries because of incomplete bladder distention. CT cystography is the preferred technique for the detection of bladder tears with a reported sensitivity and specificity of 95% and 100% respectively.6 The bladder is filled by low-gravity drip infusion of dilute water-soluble contrast material (125 milliliters [mL] of 60% water-soluble contrast agent in 375 mL of saline) using an age-based estimate of bladder capacity (4.5 × age (0.40) = capacity in ounces).7

Intraperitoneal rupture occurs when the bladder is acutely compressed resulting in a sudden increase in pressure and a tear of the dome of the bladder. This results in extravasation of contrast-containing urine into the peritoneum where it fills the cul-de-sac, surrounds the bowel, often extending into the paracolic gutters and subhepatic space (Fig. 124-4 and e-Fig 124-5). In children, intraperitoneal rupture accounts for up to 60% of all bladder tears.

Figure 124-4 Intraperitoneal bladder rupture.

An axial computed tomography cystogram image through the pelvis shows extravasation of contrast-containing urine into the cul de sac (arrows). See e-Figure 124-5.

e-Figure 124-5 Intraperitoneal bladder rupture.

Computed tomography through sacral promontory shows extravasated contrast surrounding bowel loops.

Extraperitoneal rupture is less common in children than in adults, accounting for approximately 40% of all bladder perforations. They are often associated with pelvic fractures that distort and shear the bladder at its attachments near the trigone, below the peritoneal reflection. On CT cystography, extravasation is usually confined to the perivesical soft tissues (Fig. 124-6 and e-Fig. 124-7), but may extend into the scrotum, superiorly along the anterior abdominal wall or up through retroperitoneal spaces to the level of the kidney.1,8

Figure 124-6 Extraperitoneal bladder rupture.

A coronal computed tomography cystogram image shows contained extravasation of contrast-containing urine into the perivesical spaces. See e-Figure 124-7 for the sagittal view.

Treatment: Intraperitoneal ruptures require immediate surgical repair, whereas extraperitoneal ruptures are usually treated by catheter drainage alone. Combined intraperitoneal and extraperitoneal injuries are uncommon in children and usually identified during surgical exploration. Bladder tears generally have a highly favorable outcome, unless the injury extends longitudinally through the bladder base into the proximal urethra. These injuries frequently lead to incontinence and the need for multiple additional surgeries (Fig. 124-8 and e-Fig 124-9).9

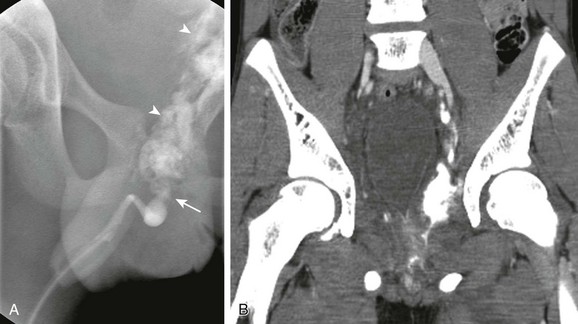

Figure 124-8 Bladder neck and urethral tear.

A, An oblique retrograde urethrogram shows complete transection (arrow) of posterior urethra and bladder neck with extraperitoneal extravasation of contrast (arrowheads). B, A coronal contrast-enhanced computed tomography image of the pelvis shows elevated bladder base, perivesical “sentinel” hematoma, and extravasated contrast. See e-Figure 124-9 for the sagittal view.

Urethral Injury

Overview: Urethral injuries can be divided into posterior and anterior urethral injuries. Most posterior urethral injuries are caused by direct blows to the perineum, falls, or motor vehicle accidents, and occur frequently in the setting of pelvic fractures. These injuries usually involve the membranous urethra and are caused by shearing and rupture of the puboprostatic ligaments. Anterior urethral injuries are usually straddle-type injuries that are rarely associated with pelvic fractures (see Fig. 124-8 and e-Fig. 124-9). Although any grade of hematuria may be associated with urethral injury, the strongest clinical sign is the presence of blood at the meatus. No urethral instrumentations should be performed in patients with suspected urethral injury until a retrograde urethrogram is performed to evaluate the integrity of the entire urethra. Attempts to catheterize the bladder may convert a partial urethral tear into a complete transection.10

Imaging: Retrograde urethrography is performed by inserting the tip of a Foley catheter into the distal urethra. The balloon is slowly inflated in the fossa navicularis, and water-soluble contrast material is injected via a syringe, with the patient positioned in the steep oblique or lateral position. Urethral injuries are manifested by irregular narrowing of the affected urethra and extravasation of contrast into the surrounding tissues (Fig. 124-10).

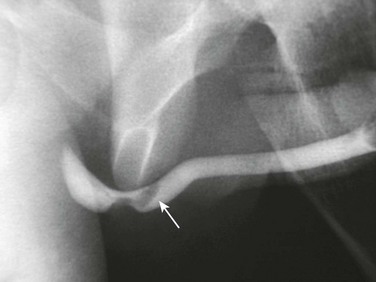

Figure 124-10 Straddle injury, membranous urethra.

An oblique retrograde urethrogram shows focal urethral narrowing and intraluminal hematoma (arrow).

Although retrograde urethrography is the preferred method of evaluating the urethra, placement of a urinary catheter is common in patients with multiple trauma, and retrograde urethrography may be initially considered only after a CT scan has already been performed. Therefore, familiarity with CT findings associated with urethral injuries is important. These include obliteration of the fat plane around the urogenital diaphragm, obscured contours of the prostate, and obturator internus muscle (see Fig. 124-8 and e-Fig. 124-9).11

Scrotal Injury

Overview: The majority of blunt injuries to the scrotum occur in older boys and are the result of a direct blow to the groin during sport activities (50%), motor vehicle crashes (9%–17%), falls, or straddle injuries. Typical indications for imaging include an acute, painful, or ecchymotic scrotum, and a nonpalpable testis. Although common, scrotal injuries rarely need surgical intervention. Fortunately, over 80% of ruptured testes can be successfully salvaged if surgical repair is performed within 72 hours of injury.10

Imaging: Ultrasonography is the most effective method of assessing the injured scrotum. High-frequency (7–14 megahertz) linear array transducers should be used to evaluate both testes with grey-scale and color or power Doppler to determine the location and extent of injury. Ultrasonography plays a key role in the identification of testicular rupture allowing for immediate surgical exploration and repair.

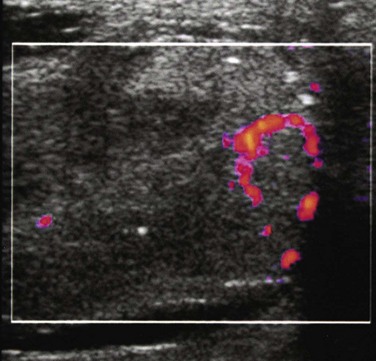

Hematomas and hematoceles are the most common findings after scrotal injury. They may be single or multiple and may have a wide range of echogenicities, depending on the time interval between injury and imaging (Fig. 124-11 and e-Fig. 124-12). With time, the contained hemorrhage becomes less echogenic, and the fluid may become more typical of hydrocele.

Figure 124-11 Scrotal hematoma.

Transverse ultrasonogram of the right scrotum shows an intact testis (arrows) surrounded by heterogeneous peritesticular hematoma. See e-Figure 124-12 for the sagittal view.

e-Figure 124-12 Scrotal hematoma.

A sagittal ultrasonogram of the right scrotum shows an intact testis (arrows) surrounded by heterogeneous peritesticular hematoma.

Testicular fractures may also occur when a break occurs in the testicular parenchyma alone or is associated with a tear in the tunica albuginea (testicular rupture). On ultrasonography, heterogeneous echogenicity to the testicular parenchyma, caused by infarction and hemorrhage is seen. Irregularity of the normally smooth testicular border and, occasionally, nonvisualization of any normal testicular parenchyma are also encountered. Ultrasonographic findings of an abnormal testicular contour and heterogeneous echotexture caused by hemorrhage and extrusion of seminiferous tubules have a high sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of testicular rupture (Fig. 124-13 and e-Fig. 124-14).

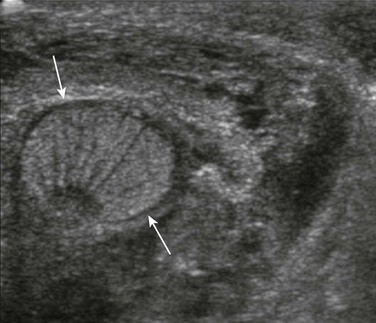

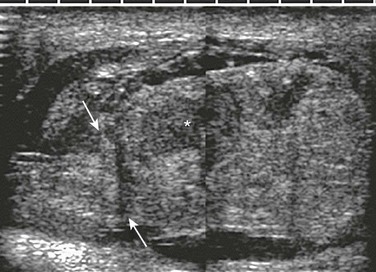

Figure 124-13 Testicular rupture.

A sagittal composite scrotal ultrasonogram shows a heterogeneous testis with intratesticular hematoma (asterisk) and extrusion of testicular contents through a tear in the tunica albuginea (arrows). See e-Figure 124-14.

e-Figure 124-14 Testicular rupture.

A power Doppler ultrasonogram of the same patient shown in Figure 124-13 shows only minimal flow in the remaining viable testis.

One must be wary of the possibility that a bizarre heterogeneous echogenicity in a traumatized scrotum may actually be a hematoma that has superiorly displaced a normal testis into the inguinal canal.10–12 Other extratesticular findings include reactive hydroceles, posttraumatic epididymitis, and testicular torsion.

Adu-Frimpong, J. Genitourinary trauma in boys. Clin Ped Emerg Med. 2009;10:45.

Bixby, SD, Callahan, MJ, Taylor, GA. Imaging in pediatric blunt abdominal trauma. Semin Roentgenol. 2008;43:72.

Gomez, RG, Ceballos, L, Coburn, M, et al. Consensus statement on bladder injuries. Br J Urol Int. 2004;94:27.

Harris, AC, Zwirewich, CV, Torreggiani, WC, et al. CT findings in blunt renal trauma. Radiographics. 2001;21:S201–S214.

Ramchandani, P, Buckler, PM. Imaging of genitourinary trauma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192:1514.

References

1. Bixby, SD, Callahan, MJ, Taylor, GA. Imaging in pediatric blunt abdominal trauma. Semin Roentgenol. 2008;43:72.

2. Taylor, GA, Eichelberger, MR, Potter, BM. Hematuria: a marker of abdominal injury in children after blunt trauma. Ann Surg. 1988;208:688.

3. Eeg, KR, Khoury, AE, Halachmi, S, et al. Single center experience with application of the ALARA concept to serial imaging studies after blunt renal trauma in children—is ultrasound enough? J Urol. 2009;181:1834.

4. Henderson, CG, Sedberry-Ross, S, Pickard, R, et al. Management of high grade renal trauma: 20-year experience at a pediatric level I trauma center. J Urol. 2007;178:246.

5. Gomez, RG, Ceballos, L, Coburn, M, et al. Consensus statement on bladder injuries. Br J Urol Int. 2004;94:27.

6. Quagliano, PV, Delair, SM, Malhotra, AK. Diagnosis of blunt bladder injury: a prospective comparative study of computed tomography cystography and conventional retrograde cystography. J Trauma. 2006;61:410.

7. Kaefer, M, Zurakowski, D, Bauer, SB, et al. Estimating normal bladder capacity in children. J Urol. 1997;158:2261.

8. Sivit, CJ, Cutting, JP, Eichelberger, MR. CT diagnosis and localization of rupture of the bladder in children with blunt abdominal trauma: significance of contrast material in the pelvis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1995;164:1243.

9. Routh, JC, Husmann, DA. Long-term continence outcomes after immediate repair of pediatric bladder neck lacerations extending into the urethra. J Urol. 2007;178:1816.

10. Adu-Frimpong, J. Genitourinary trauma in boys. Clin Ped Emerg Med. 2009;10:45.

11. Ramchandani, P, Buckler, PM. Imaging of genitourinary trauma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192:1514.

12. Bhatt, S, Dogra, VS. Role of US in testicular and scrotal trauma. Radiographics. 2008;28:1617.