Chapter 19 Female genital tract

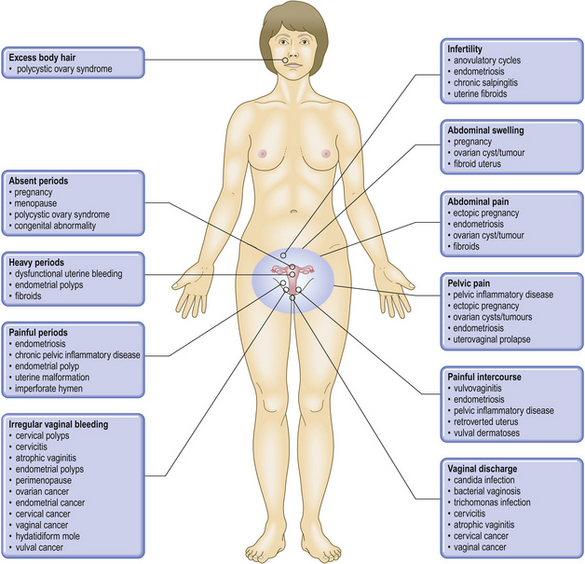

COMMON CLINICAL PROBLEMS FROM FEMALE GENITAL TRACT DISEASE

Pathological basis of signs and symptoms in the female genital tract

| Sign or symptom | Pathological basis |

|---|---|

| Vaginal bleeding | |

Haemorrhage from placenta (e.g. placenta praevia), placental bed (e.g. miscarriage) or decidua (e.g. ectopic pregnancy)

Haemorrhage from lesion on cervix (e.g. carcinoma)

Haemorrhage from uterine lesion (e.g. polyp, carcinoma)Abnormal menstruation (timing or volume of loss)

Pain

Abdominal distension

Diseases of the female genital tract include inflammation, neoplasia, hormonal disturbances and complications of pregnancy. The commonest disorders are discussed here on a topographical basis.

NORMAL DEVELOPMENT

Female sexual development

Female development does not require the presence of a gonad, and the ovary plays no part in primary sexual development. This means that a neuter embryo will always develop along female lines. The testis-determining factor is the SRY gene carried in the sex-determining region of the Y chromosome. The indifferent gonad develops into an ovary when no Y chromosome is present, although two functional X chromosomes are usually required for normal ovarian differentiation. Disorders of female sexual development are listed in Table 19.1.

Table 19.1 Abnormalities of female sexual development

| Sex chromosomes | Gonads | Possible abnormalities |

|---|---|---|

| Normal XX | Bilateral normal ovaries | Congenital adrenal hyperplasia |

| Maternal androgen or progestagen administration in pregnancy | ||

| Maternal virilising tumour in pregnancy | ||

| Normal XX or XY | Abnormal (streak gonads)∗ | Gonadal dysgenesis |

| Ovaries (XY) or testes (XX)∗ | Inappropriate gonads for chromosomes | |

| Abnormal | Turner’s syndrome | |

| Mixed gonadal dysgenesis | ||

| True hermaphroditism |

∗ Diagnosis of a specific type of intersex requires histological confirmation of gonadal status; ovotestis can look macroscopically exactly like a normal ovary, or the patient could have one macroscopically normal testis on one side and an ovary on the other.

Embryological development

Germ cells arise in the wall of the yolk sac, and migrate to the region of the coelomic germinal epithelium. In the sixth week cords of cells appear within the indifferent gonad, but it is not until after the seventh week that ovarian differentiation is apparent and by 14 weeks these cell cords surround the primordial follicles.

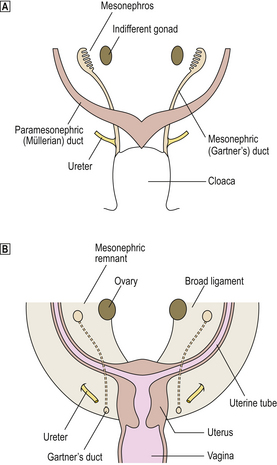

The paired paramesonephric Müllerian ducts arise as an invagination of the coelomic epithelium of the mesonephric ridge lateral to the mesonephric duct. The paramesonephric duct follows the mesonephric duct. Near the cloaca, the paramesonephric ducts cross from the lateral to the medial side of the mesonephric ducts (Fig. 19.1A); together they carry with them some mesoderm from the side walls of the pelvis to create the transverse bar which helps to form the septum dividing the rectum from the urogenital sinus.

Fig. 19.1 Development of the female genital tract.  Frontal view of the posterior wall of 7-week embryo showing the mesonephric and paramesonephric ducts during the indifferent stage of development.

Frontal view of the posterior wall of 7-week embryo showing the mesonephric and paramesonephric ducts during the indifferent stage of development.  Female genital tract in a newborn infant.

Female genital tract in a newborn infant.

At the 30-mm stage (8 weeks), fusion of the parameso-nephric ducts creates the utero-vaginal canal, which ultimately forms the uterus and proximal part of the vagina (Fig. 19.1B); the unfused parts form the uterine tubes. The trans-pelvic bar, which is a continuation of the mesonephric mesentery, forms the broad ligament; the ovary, projecting medially from the mesonephric ridge in the early stage, comes to lie posterior to the broad ligament. The inferior free end of the fused paramesonephric ducts (utero-vaginal canal) is still solid, and the sino-vaginal bulbs grow out from the posterior wall of the urogenital sinus to fuse with it and, later, give rise to the lower part of the vagina. The hymen occupies the position where the sino-vaginal bulb and urogenital sinus meet. The gonads are at first elongated and lie in the long axis of the embryo. Later, each gonad assumes a transverse lie. The gubernaculum is formed in the inguinal fold as a fibromuscular band which burrows from the gonad to gain attachment to the genital swelling; thus the caudal pole of the gonad becomes relatively fixed. The gubernaculum persists as the round ligament of the uterus. The ovaries retain attachment to the posterior aspect of the broad ligament. The genital swellings form the labia majora, the genital folds form the labia minora, and the genital tubercle forms the clitoris.

VULVA

A variety of skin disorders, including inflammatory lesions, may manifest themselves in the vulva. Candidal infection may occur, particularly in diabetics. These disorders are discussed in Chapter 24. Vulval condylomata (viral warts) are discussed below.

Herpes virus infection

Sexually transmitted herpes virus infection is usually due to herpes simplex type 2, and produces painful ulceration of the vulval skin. Histologically, intra-epithelial blisters are seen, accompanied by specific cytopathic effects characterised by intranuclear viral inclusions and eosinophilic cytoplasmic swelling.

Syphilis

Primary and secondary syphilitic lesions may affect the vulva. The condyloma latum of secondary syphilis is characterised by oedematous, acutely inflamed, hyperplastic epithelium with underlying chronic inflammation, including prominent plasma cells. Hypertrophy of endothelial cells (‘endarteritis obliterans’) may occur. A silver stain may be used to demonstrate spirochaetes.

Granuloma inguinale (donovanosis)

This sexually transmitted disease caused by the Gram-negative bacillus Calymmatobacterium granulomatis is found throughout the tropics. It commonly causes chronic vulval ulceration but may spread to other sites in the female genital tract. Characteristically, large macrophages with clear or foamy cytoplasm containing bacilli (Donovan bodies) are seen, demonstrated with the help of Giemsa or silver stains.

Lymphogranuloma venereum

This sexually transmitted disease is caused by Chlamydia trachomatis and is most prevalent in the tropics. The earliest lesion is a vesicle which breaks down to form a punched-out painless ulcer. The primary lesion may become secondarily infected with abundant granulation tissue, fibrosis, fistula formation and lymphatic obstruction characterising the chronic form of the disease. Necrotising granulomas may occur in inguinal lymph nodes.

Candidiasis

Candida may cause chronic irritation and inflammation of the vulva that may be associated with vaginitis. The diagnosis may be made by microscopic examination of skin scrapings or culture. The histological features are non-specific, although the fungi may be identified within the keratin layer or superficial epithelium with the use of silver stains.

Cysts and tumours

Any benign cyst or tumour of the skin may be seen in the vulva. Two uncommon benign tumours are worthy of comment because of their distinct histological appearance: papillary hidradenoma and granular cell tumour.

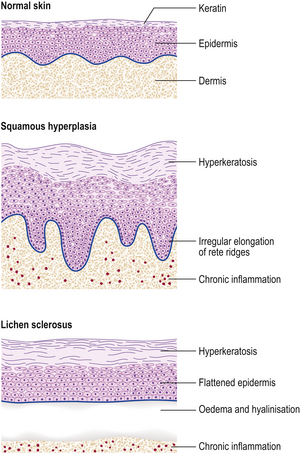

NON-NEOPLASTIC EPITHELIAL DISORDERS

The term ‘non-neoplastic epithelial disorders’ (Fig. 19.2) encompasses a group of vulval disorders of uncertain aetiology which affect all age groups, although predominantly peri- and post-menopausal women. In the past, these disorders have been given a confusing variety of clinical labels. They often appear clinically as ‘leukoplakia’, a term that refers to the white appearance of the skin and which should never be used in a pathological context. The clinical appearance of ‘leukoplakia’ is due to hyperkeratosis. In about 5% of cases there is a risk of squamous carcinoma, so that the presence or absence of cytological atypia (vulval intra-epithelial neoplasia) in biopsies should always be reported. There are two basic types of non-neoplastic epithelial disorder of the vulva: squamous hyperplasia and lichen sclerosus; these may sometimes co-exist.

Squamous hyperplasia

Vulval squamous hyperplasia is characterised by hyperkeratosis, irregular thickening of the epidermal rete ridges, and chronic inflammation of the superficial dermis.

Lichen sclerosus

Lichen sclerosus, like hyperplasia, shows hyperkeratosis, but there is thinning of the epidermis with flattening of the rete ridges. The most characteristic feature is a broad band of oedema and hyalinised connective tissue in the superficial dermis. Beneath this, there may be mild chronic inflammation. Lichen sclerosus has a lower neoplastic potential than squamous hyperplasia.

NEOPLASTIC EPITHELIAL DISORDERS

Intra-epithelial neoplasia

The term intra-epithelial neoplasia refers to the spectrum of pre-invasive neoplastic change affecting the vulva. Its classification is the same as that of similar lesions in the cervix, although it may be incorrect to draw too close an analogy with the cervix as far as natural history is concerned. It is a condition that predominantly affects young women, and is associated with high-risk human papillomavirus infection (see below). In severe cases, there may be extensive involvement of the perineum, including the peri-anal area. The incidence of malignant change occurring in these lesions is low compared with that for the cervix. There is a tendency for intra-epithelial neoplasia to occur multifocally, with synchronous or metachronous involvement of vulva, vagina and cervix.

Squamous carcinoma

Squamous carcinoma (Fig. 19.3) is a tumour predominantly affecting elderly women in whom it is not usually associated with human papillomavirus infection. The recognition of associated intra-epithelial neoplasia may be difficult as it may occur in a so-called ‘differentiated’ form. The appearances are those of squamous carcinoma in any site; thus the tumour may be well, moderately or poorly differentiated. The prognosis is determined by the size, depth of invasion and degree of histological differentiation of the tumour, and the presence and extent of lymph node metastases, which predominantly affect the inguinal lymph nodes.

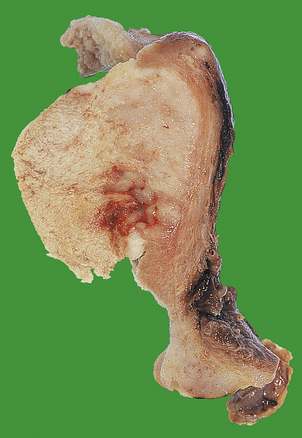

Fig. 19.3 Vulval squamous carcinoma. Surgical resection showing a large, fungating and invasive tumour on the vulva of an elderly patient.

In contrast to squamous carcinoma of the cervix, even minimally invasive disease in the vulva is associated with a risk of local lymph node metastasis, although this risk seems to be negligible for carcinoma invading to a depth of less than 1 mm. Tumour thickness greater than 5 mm and positive lymph nodes are associated with a poor prognosis.

Paget’s disease

The rare occurrence of mucin-containing adenocarcinoma cells within the squamous epithelium of the vulva is analogous to Paget’s disease of the breast (Ch. 18). Paget’s disease of the vulva tends to be chronic, with multiple recurrences. It may be indicative of an underlying invasive adenocarcinoma (in about 25% of cases), usually of skin adnexal origin, although, unlike the equivalent breast lesion, this is not usual. Adenocarcinomatous differentiation within the squamous epithelium has also been proposed as a possible explanation.

VAGINA AND CERVIX

The commonest diseases affecting the vagina and cervix are infections, many of which are transmitted sexually. Tumours and pre-neoplastic lesions of the cervix, of which squamous cell carcinoma is the most important, are associated with human papillomavirus infection.

Infections

Vaginal infections are common and often sexually transmitted. The organisms of most importance are: Gardnerella vaginalis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Candida albicans and Trichomonas vaginalis.

Vaginal adenosis

The occurrence of glands within the subepithelial connective tissue of the vagina is uncommon, and is believed to be due to a defect in embryological development. The lining of these glands is usually a mucinous cuboidal epithelium which may undergo squamous metaplasia. Vaginal adenosis particularly affected young females who were exposed to diethylstilbestrol in utero. This synthetic oestrogenic agent was used in the 1950s in the treatment of threatened miscarriage in the USA and, to a lesser extent, in the UK. Clear cell adenocarcinoma of the vagina may rarely complicate adenosis.

Vaginal intra-epithelial neoplasia

Vaginal intra-epithelial neoplasia is much less common than cervical intra-epithelial neoplasia but the same diagnostic criteria are applied. The lesion may co-exist with similar lesions of the vulva and cervix (reflecting the multicentric origin of squamous neoplasia).

Vaginal squamous carcinoma

Vaginal squamous carcinoma is an uncommon tumour predominantly occurring in older women. Pathologically, the tumour resembles squamous carcinoma of the cervix but it has a propensity to local invasion and radical surgery may be necessary.

Cervicitis

Non-specific acute and/or chronic inflammation is common in the cervix, particularly in the presence of an intra-uterine contraceptive device, ectopy (see below) or prolapse.

Chlamydiae are obligate intracellular organisms containing DNA and RNA, and are larger than viruses. Chlamydia trachomatis is a common sexually transmitted infection which is often recognised by its persistence following treatment for gonorrhoea in males (post-gonococcal urethritis). Chlamydiae can be isolated from the cervices of about 50% of asymptomatic female partners of these infected males and from women with chronic cervicitis. Chlamydial infection may produce subepithelial reactive lymphoid follicles, a condition sometimes given the label of ‘follicular cervicitis’.

Cervical polyps

Benign polyps of the cervix are common. They are composed of columnar mucus-secreting epithelium and oedematous stroma. Vessels may be prominent and there may be acute or chronic inflammation of varying severity. These polyps have no malignant potential.

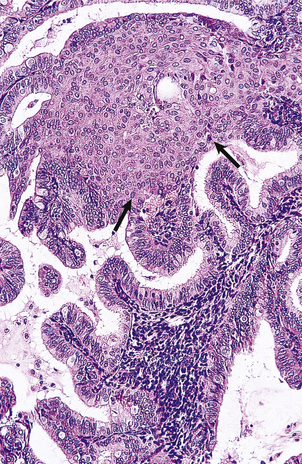

Cervical microglandular hyperplasia

Cervical microglandular hyperplasia is a commonly seen complex glandular proliferation that may be confused with carcinoma. Small, tightly packed glands, lined by low columnar or cuboidal epithelium, may form polypoid projections into the endocervical canal. Accompanying acute inflammation and reserve cell hyperplasia (see below) are often seen. These changes may be seen in pregnancy and in users of the oral contraceptive pill, where they are the result of high levels of progestogen. Microglandular hyperplasia may also rarely be seen in post-menopausal women. It appears to have no malignant potential.

CERVICAL SQUAMOUS NEOPLASIA

Aetiology

Squamous neoplasia of the cervix is associated with sexual activity; early age at first intercourse, frequency of intercourse and number of sexual partners are all risk factors. The sexual behaviour of the male partner is probably also of importance. There is probably no one single cause of cervical cancer or pre-cancer, but epidemiological evidence points to a sexually transmitted agent or agents. There is now compelling evidence that human papillomaviruses are implicated in the aetiology of cervical squamous neoplasia. Cigarette smoking is an independent risk factor; some contents of cigarette smoke, which can be detected in cervical mucus, may act as co-carcinogenic agents. The polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in cigarette smoke form damaging adducts with DNA; these have been demonstrated in cervical tissue at higher levels in current smokers.

Human papillomaviruses and neoplasia of the lower female genital tract

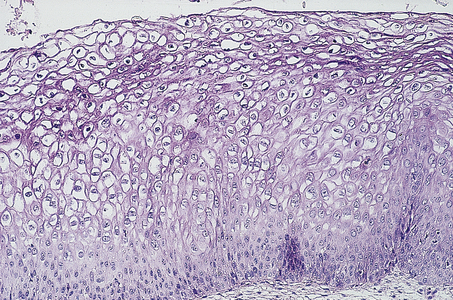

Genital warts or condylomata have been recognised for centuries. Only comparatively recently, however, has their viral aetiology been established. Electron microscopy showed the presence of viral particles, and immunohistochemistry (using antibodies to viral capsid antigen) and in situ hybridisation (using DNA probes) also confirmed their viral nature. Warts may affect the vulva but may also involve the cervix (Fig. 19.4). Moreover, it is now appreciated that human papillomaviruses (HPV) may infect the vulva, vagina and cervix in a non-condylomatous manner. Such infections show characteristic morphological features; most important of these is a specific cytoplasmic vacuolation called koilocytosis (Fig. 19.5). The features associated with human papillomavirus infection are:

Fig. 19.5 Koilocytosis. Cytoplasmic vacuolation and pyknotic nuclei indicative of human papillomavirus infection of the cervix.

These morphological features are also common accompaniments of vulval, vaginal and cervical intra-epithelial neoplasia.

There are now more than 100 subtypes of human papillomavirus recognised and certain of these show a particular predilection for the lower female genital tract, notably HPV 6, 11, 16 and 18. HPV 6 and 11 are found in benign condylomata and are only rarely implicated in malignant transformation. HPV 16 and, to a lesser extent, 18 are found in cervical intra-epithelial neoplasia and in nearly 100% of cervical carcinomas. Other types, such as HPV 31 and 33, have also been reported in carcinoma. These are the oncogenic HPV types. Infection of the male genitalia by HPV is also seen; similar lesions to those seen on the cervix occur on the glans penis and prepuce, and may also be associated with neoplastic change.

Papillomavirus DNA may be present either extrachromosomally (episomal) or integrated into the host DNA. Integration of the viral genome into host DNA is usual in high-grade cervical intra-epithelial neoplasia (see below) and invasive cervical squamous carcinoma. The protein coding sequences of the viral early (E) or late (L) open reading frames appear to have a major role in oncogenesis. Most interestingly, the E6 protein of HPV type 16 is capable of binding to the cellular p53 protein to form a complex that neutralises the normal response of cervical epithelial cells to DNA damage (apoptosis mediated by p53), which may thereby allow the accumulation of genetic abnormalities. E6 protein of low-risk HPV types (e.g. 6 and 11) does not appear to form a complex with p53.

These events may explain why, unlike many other solid tumours, mutation of the p53 gene is an uncommon event in cervical carcinogenesis, as there is an alternative mechanism for its inactivation.

HPV 16 and 18 E7 proteins also have the ability to bind to the product of the retinoblastoma gene (RB1), thus affecting its tumour suppressor role.

HPV vaccination is now being implemented in many countries. The vaccine comprises virus-like particles produced by recombinant DNA technology.

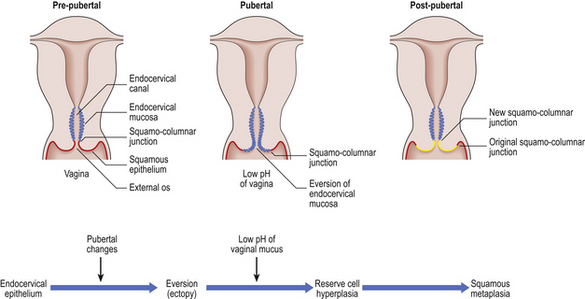

Physiological and neoplastic changes in the cervical transformation zone

Before puberty, the squamo-columnar junction lies within the endocervical canal (Fig. 19.6). With the onset of puberty and in pregnancy, there is eversion of the columnar epithelium of the endocervix so that the squamo-columnar junction comes to lie beyond and on the vaginal aspect of the external os. This produces the clinical appearance of a cervical ‘erosion’, an unfortunate term, as the change is physiological. The term ectopy is more appropriate. The columnar epithelium is then exposed to the low pH of the vaginal mucus and undergoes squamous metaplasia. This is a physiological phenomenon, and takes place through the stages of reserve cell hyperplasia and immature squamous metaplasia. Reserve cells undermine the columnar mucus-secreting cells and multiply. This labile epithelium is called the transformation zone and is the predominant site for the development of cervical neoplasia.

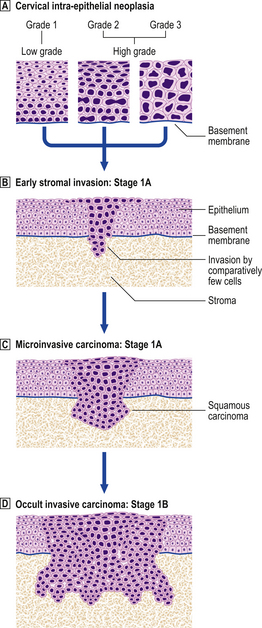

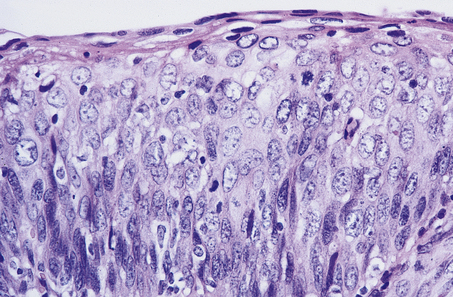

Cervical intra-epithelial neoplasia (CIN) refers to the spectrum of epithelial changes that take place in squamous epithelium as the precursors of invasive squamous carcinoma. The severity of the lesion is assessed subjectively as grade (CIN) 1 (low grade), 2 or 3 (high grade), according to the level in the epithelium at which cytoplasmic maturation is taking place (Fig. 19.7). Abnormal nuclei are present throughout the thickness of the epithelium, and mitotic figures are not confined to the basal cell layer (Fig. 19.8). Any grade of cervical intra-epithelial neoplasia is potentially invasive, although the risk of invasion becomes greater as the severity of the lesion increases. The rate at which these intra-epithelial lesions progress and the proportion of cases that would progress if left untreated is uncertain, but probably about 11% of CIN 1 cases will progress to CIN 3 within 3 years. More than 12% of cases of CIN 3 would progress to invasion if left untreated; about 30% of cases would regress. The presence of abnormal mitotic figures is associated with progression. It is also the case that, in some young women, the lesions progress to invasive carcinoma more quickly (3 years or less). The categorisation of cervical neoplasia into low (CIN 1) and high (CIN 2 and 3) grade intra-epithelial neoplasia reflects the clinical management of the disease.

Fig. 19.7 Cervical intra-epithelial neoplasia (CIN) and invasive squamous carcinoma.  Cervical intra-epithelial neoplasia. The concept of CIN refers to the level in the epithelium at which cytoplasmic maturation occurs. Grade 1 represents mild dysplasia; nuclear abnormalities throughout the epithelium, and cytoplasmic differentiation in the upper two-thirds are present. Grade 2 represents moderate dysplasia, with differentiation in the upper third of the epithelium. Grade 3 represents severe dysplasia and carcinoma in situ.

Cervical intra-epithelial neoplasia. The concept of CIN refers to the level in the epithelium at which cytoplasmic maturation occurs. Grade 1 represents mild dysplasia; nuclear abnormalities throughout the epithelium, and cytoplasmic differentiation in the upper two-thirds are present. Grade 2 represents moderate dysplasia, with differentiation in the upper third of the epithelium. Grade 3 represents severe dysplasia and carcinoma in situ.  Early stromal invasion. Invasion is < 1mm and there is a negligible risk of lymph node spread.

Early stromal invasion. Invasion is < 1mm and there is a negligible risk of lymph node spread.  Microinvasive carcinoma. Invasion is <3 mm in depth and the maximum horizontal dimension of the tumour is < 7 mm. There is still < 1% risk of lymph node spread. The presence of tumour within local lymphatic or vascular channels does not affect this definition.

Microinvasive carcinoma. Invasion is <3 mm in depth and the maximum horizontal dimension of the tumour is < 7 mm. There is still < 1% risk of lymph node spread. The presence of tumour within local lymphatic or vascular channels does not affect this definition.  Occult invasive carcinoma. Invasion is > 500 mm3 and there is some risk of lymph node spread, but the tumour is still clinically undetectable.

Occult invasive carcinoma. Invasion is > 500 mm3 and there is some risk of lymph node spread, but the tumour is still clinically undetectable.

Fig. 19.8 Cervical intra-epithelial neoplasia (CIN) grade 3. Note that there is minimal surface differentiation.

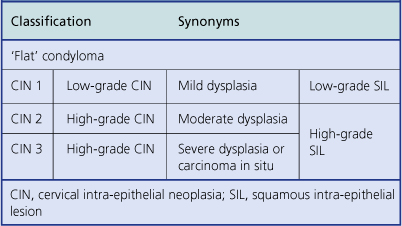

The terms low-grade and high-grade squamous intra-epithelial lesion (SIL) are used in some countries, notably the USA (Table 19.2).

Cytology screening programmes

Cytology screening programmes are sometimes referred to erroneously as cervical cancer screening. This is incorrect because the aim is to detect atypical cells by cervical cytology in the pre-invasive stage of the disease. The abnormal epithelium can then be eradicated by local measures, such as diathermy large loop excision of the transformation zone (LLETZ).

Cervical cytology is a simple, safe, non-invasive method of detecting precancerous changes in the cervix. The majority of specimens submitted to the pathology laboratory are taken from asymptomatic women as part of a national screening programme. The incidence of and mortality from invasive cervical cancer has fallen dramatically in communities where intensive screening has been carried out. The rates of cervical cancer would be at least 50% greater if there was no screening programme; attendance for regular screening prevents up to 90% of cervical cancer.

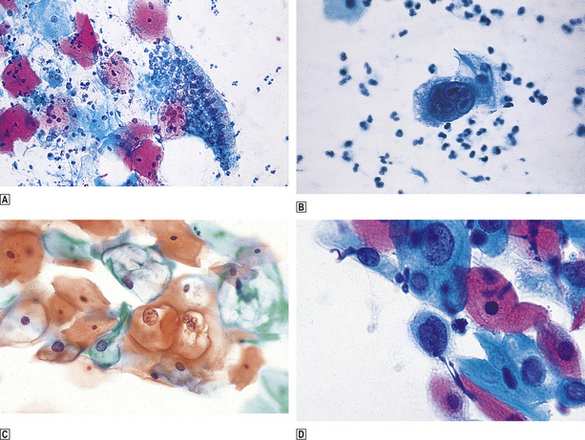

The examination of a cervical cytology specimen relies on the identification of abnormal (dyskaryotic) nuclei (Fig. 19.9). The degree of abnormality may be mild, moderate or severe, but does not always correlate with subsequent histological findings in a biopsy specimen. Therefore, even women with mildly dyskaryotic cervical cytology specimens should be referred for colposcopy (Table 19.3). Cytology is not a reliable means of detecting an invasive tumour; the diagnosis of invasive carcinoma of the cervix is largely clinical and is confirmed by biopsy of suspicious areas of the cervix. The morphological abnormalities of the nucleus (dyskaryosis) in cervical cytology specimens are:

Fig. 19.9 Cervical cytology.  Normal.

Normal.  Herpes virus infection; note the large multinucleated cell.

Herpes virus infection; note the large multinucleated cell.  Koilocytosis; the sharply defined perinuclear pallor indicates HPV infection.

Koilocytosis; the sharply defined perinuclear pallor indicates HPV infection.  Dyskaryosis; enlarged nuclei with a coarse chromatin pattern. Papanicolaou staining; hence ‘Pap’ test.

Dyskaryosis; enlarged nuclei with a coarse chromatin pattern. Papanicolaou staining; hence ‘Pap’ test.

Table 19.3 Clinical consequences of cervical cytology

| Cytological finding | Clinical consequence |

|---|---|

| Unsatisfactory | Repeat immediately |

| Normal | 3- or 5-yearly recall |

| ‘Borderline’ changes or mild dyskaryosis | Repeat in 6 months |

| Persistent ‘borderline’ changes or mild dyskaryosis | Refer for colposcopy |

| Moderate/severe dyskaryosis | Refer for colposcopy |

In many centres liquid-based cytology (LBC), in which cells are received by the laboratory suspended in fluid and prepared as a near monolayer on a slide and stained, has replaced the smearing of cells onto a glass slide from a spatula.

Invasive squamous carcinoma

The earliest sign of malignancy is early stromal invasion when small foci (less than 1 mm) are seen to arise from the basal epithelium and to breach the integrity of the basement membrane (Fig. 19.7). The concept of a microinvasive carcinoma is one in which there is a negligible risk of lymph node metastasis so that conservative management is appropriate. The tumour spreads by local and lymphatic invasion. The two principal factors that determine the prognosis of cervical carcinoma are:

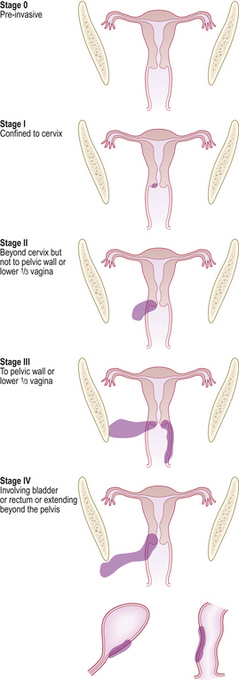

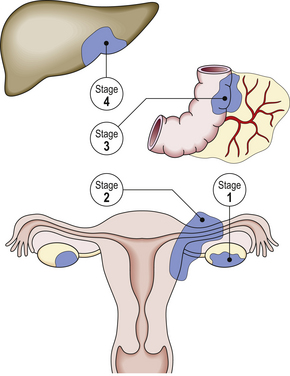

The staging of cervical cancer is based on clinical and pathological assessment. Stage I cervical cancer is strictly confined to the cervix, stage II cancer extends beyond the cervix but has not extended onto the pelvic wall. It involves the vagina but not the lower third. Stage III cancer may extend onto the pelvic wall and involves the lower third of the vagina, and stage IV implies extension outside the reproductive tract. Tumour may then involve the adjacent organs, e.g. the mucosa of the bladder or rectum (Fig. 19.10).

Fig. 19.10 Stages of cervical carcinoma. The staging is based on the anatomical extent of the tumour within and beyond the cervix. Accurate staging ensures that the woman receives optimal treatment. Stage 0: Pre-invasive. Stage I: Confined to cervix. Stage II: Beyond cervix but not to pelvic wall or lower one-third of vagina. Stage III: To pelvic wall or lower one-third of vagina. Stage IV: Involving bladder or rectum or extending beyond the pelvis.

Involvement of para-aortic nodes is associated with a uniformly poor prognosis. The degree of histological differentiation of squamous carcinoma (whether it is well, moderately or poorly differentiated) is also an important factor.

GLANDULAR NEOPLASIA OF THE CERVIX

Glandular neoplasia of the cervix occurs less commonly than squamous neoplasia, but its incidence is increasing. Cervical glandular intra-epithelial neoplasia (CGIN) is recognised as the precursor of invasive adenocarcinoma and is being recognised more frequently. It occurs at a younger age than malignant glandular neoplasia. The recognition of neoplastic glandular cells in a cervical cytology specimen can be difficult. The long-term use of oral hormonal contraceptive preparations may be implicated in the aetiology of glandular neoplasia.

The mode of spread of the malignant tumour is the same as that of squamous carcinoma. It is increasingly recognised that a significant proportion of cervical cancers (perhaps as high as 25%) are mixed adenosquamous carcinomas. This is understandable if one considers that ‘atypical’ reserve cells may differentiate along squamous or glandular lines to give pure or mixed tumours.

OTHER MALIGNANT TUMOURS

Small cell (neuroendocrine) carcinoma of the cervix is an uncommon, but highly malignant, tumour at this site analogous to small cell carcinoma of the lung (Ch. 14). Other malignant tumours of the cervix are rare; they include sarcoma, malignant melanoma and lymphoma.

UTERINE CORPUS

Diseases affecting the uterine corpus (body of the uterus) may arise primarily within the endometrial lining (e.g. adenocarcinoma) or the myometrial wall (e.g. ‘fibroids’). Pathological complications of pregnancy may also affect the uterus, but these conditions are dealt with in a separate section.

CONGENITAL ABNORMALITIES

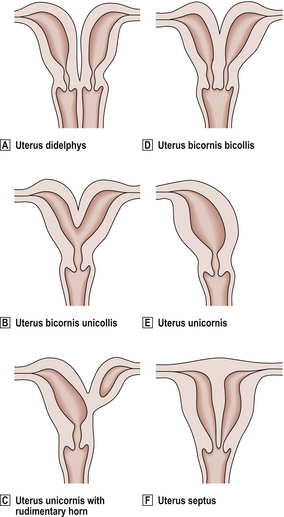

Atresias and aplasias of the female genital tract are rare, with the exception of imperforate hymen. The majority of congenital abnormalities result from a partial or complete failure of the paramesonephric (Müllerian) ducts to fuse (Fig. 19.11). The major problems associated with these anomalies relate to pregnancy, with miscarriage and obstetric complications being the most common.

THE NORMAL ENDOMETRIUM AND MENSTRUAL CYCLE

At the onset of puberty, the first signs of oestrogenic stimulation of the endometrium appear and are soon followed by the first menstrual cycles, most of which are anovulatory.

The following discussion relates to a normal menstrual cycle of 28 days. The normal endometrium responds to the cyclical production of hormones by the ovary. During the follicular or proliferative phase of the cycle, rising levels of pituitary follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) stimulate the ovary to produce oestrogens, which in turn stimulate the endometrium to proliferate. There is growth of endometrial glands and stroma, both of which show mitotic activity, and vessels become increasingly coiled. Following ovulation at about day 14 of the cycle (mediated by pituitary luteinising hormone and a further output of FSH) the follicle is transformed into a corpus luteum, which continues to secrete oestrogens and also large quantities of progesterone. This post-ovulatory or luteal phase is associated with secretory changes in the endometrium which can be recognised in three stages:

These changes prepare the endometrium for implantation of the blastocyst following fertilisation. If this does not occur there is functional decline as the corpus luteum atrophies, with falling levels of oestrogens and progesterone. This leads to the stromal haemorrhage and crumbling of the menstrual phase endometrium, which is quite variable in duration. Further proliferative activity is initiated with the development of a new follicle.

ABNORMALITIES OF THE ENDOMETRIUM

Disorders of the menstrual cycle leading to abnormal appearances of the endometrium will be discussed, followed by iatrogenic changes, polyps, endometrial hyperplasia and neoplasia. It must be remembered that many cases of abnormal uterine bleeding show a morphologically normal uterus. Defects in local haemostasis and hormonal dysfunction are important causes of bleeding in this context.

Luteal phase insufficiency

In some cases of primary or secondary infertility, endometrium examined in the secretory or luteal phase of the cycle shows inadequate secretory maturation for the appropriate estimated post-ovulatory day. Glandular and stromal maturation may also appear to be out of phase (so-called ‘irregular ripening’). These changes are usually due to diminished production of progesterone by the corpus luteum.

Irregular shedding

Irregular shedding presents with abnormal uterine bleeding, and a confusing combination of secretory, menstrual and proliferative changes are seen in endometrial biopsy specimens. The changes are the result of a persistent corpus luteum.

Arias-Stella phenomenon

The Arias-Stella phenomenon is a hypersecretory response of the endometrium to high levels of circulating progesterone. It is characterised by cytoplasmic vacuolation and cytological atypia. The presence of the Arias-Stella phenomenon in the absence of other evidence of intra-uterine pregnancy (i.e. trophoblast—see below) suggests the possibility of extra-uterine pregnancy.

Endometritis

It is unusual for the endometrium to be the site of inflammation. The commonest situation in which this occurs is after intra-uterine pregnancy, when the appearances are of non-specific acute or chronic inflammation. This may follow instrumentation or the retention of products of conception. Inflammation may also result from the presence of an intra-uterine contraceptive device (see below).

Two important specific infections of the endometrium are chlamydial infection and tuberculosis.

Chlamydial infection

Chlamydial infection produces a severe acute inflammation or chronic endometritis, with an extensive lymphocytic infiltrate and lymphoid follicle formation.

Tuberculosis

Secondary tuberculous infection of the endometrium may occur. Typical caseating or non-caseating granulomas are best seen in the secretory phase of the menstrual cycle. Definitive diagnosis rests on the demonstration of acid–alcohol-fast bacilli by the Ziehl–Neelsen technique. Endometrial infection may be associated with other evidence of pelvic or peritoneal tuberculosis.

Iatrogenic changes in the endometrium

Changes may be induced in the endometrium as a result of:

Oral contraceptive preparations

There are two main types of oral contraceptive ‘pill’:

The commoner pill now in use is the combined preparation: low doses of oestrogen and progestogen are currently used. The commonest appearance in the endometrium is that of small, tubular, relatively inactive glands in a poorly developed stroma. Long-term use of the contraceptive pill in women over the age of 35 (particularly smokers) may be associated with hypertension, subarachnoid haemorrhage, thrombo-embolic phenomena and gallstones.

For the purpose of contraception, progestogens alone may be administered as a long-term intramuscular injection or as a daily oral preparation. Glandular atrophy and stromal pseudo-decidualisation are the usual changes produced. Oral progestogen given for the treatment of uterine bleeding secondary to ovarian dysfunction or endometrial hyperplasia produces similar effects.

Hormone replacement therapy

Exogenous oestrogen is used in the treatment of peri- and post-menopausal symptoms. It is of great potential benefit in the prevention of post-menopausal osteoporosis. There is, however, a risk of endometrial hyperplasia (20% after 1 year of treatment) and adenocarcinoma (relative risk 2.3) with unopposed exogenous oestrogen so that post-menopausal hormone replacement therapy in the presence of a uterus should involve a combination of oestrogen and progestogen. The progestogen opposes the potentially deleterious effects of oestrogen on the endometrium. The two hormones may be taken as ‘sequential’ or ‘continuous combined’ preparations. Oestrogens may also be delivered as an impregnated skin patch.

Intra-uterine devices

The precise mode of action of intra-uterine contraceptive devices is uncertain (Fig. 19.12). They may act by preventing fertilisation or blastocyst implantation, or by inducing very early miscarriage of an implanted pregnancy. The following pathological changes related to the presence of an intra-uterine device may be seen in the endometrium:

Fig. 19.12 An intra-uterine contraceptive device (Copper-7). Hysterectomy specimen opened to expose the device.

Not all of these changes produce symptoms. Pelvic infection with Actinomyces-like organisms may occur with any of these devices.

Some intra-uterine devices contain a progestogen preparation, in which case the endometrial changes associated with exogenous progestogen administration (see above) are also seen.

Tamoxifen

Tamoxifen is an anti-oestrogenic agent used in the treatment of breast cancer. Paradoxically, it also has oestrogenic effects and endometrial abnormalities may occur following its long-term use; these include endometrial polyps and adenocarcinomas. The risk of developing endometrial cancer in patients treated with tamoxifen is still low (1.2 per 1000 person-years).

Endometrial polyps

Endometrial polyps are common in peri-menopausal and post-menopausal endometrium, and may be single or multiple. They are the result of the inappropriate reaction of foci of endometrium to oestrogenic stimulation. They are composed of variably sized glands, which are often cystic and are set in a cellular stroma which characteristically contains thick-walled blood vessels. The epithelium lining the glands may show variable metaplasia, and secondary inflammatory changes may occur. Malignant change is possible, although uncommon.

Endometrial hyperplasia

The endometrium undergoes hyperplasia in response to unopposed oestrogenic stimulation. The source of oestrogenic stimulation may be endogenous, such as an ovarian tumour, the polycystic ovary syndrome (see below) or exogenous. Obesity is an important cause of a hyperoestrogenic state, as there is increased peripheral conversion of androstenedione to oestrone by the enzyme, aromatase, in fat cells. The various types of endometrial hyperplasia discussed below are associated with a variable risk of malignant change. The precise factors that determine which type will develop in a particular patient are unknown.

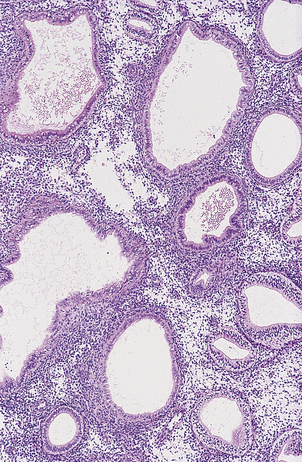

Simple hyperplasia

Simple hyperplasia is a diffuse abnormality affecting the whole of the endometrium. Many of the glands are dilated, and the epithelium shows increased nuclear stratification. The stroma also shows increased mitotic activity but there is no nuclear atypia (Fig. 19.13). This form of hyperplasia is associated with no increased risk of malignancy.

Complex hyperplasia

Complex hyperplasia is usually a focal architectural change in the endometrium. Characteristically, the glands are crowded and irregularly branched (Fig. 19.14). There is a low risk of malignant change (3%).

Atypical hyperplasia

In atypical hyperplasia (endometrial intra-epithelial neoplasia) architectural and cytological changes are combined. The nuclei of the epithelial cells may show a variable degree of cytological atypia (Fig. 19.15). There is a close correlation between the risk of malignant change and the severity of the atypia. Thus, for atypical hyperplasia showing a severe degree of cytological atypia, the risk is probably about 25% after 3 years.

Endometrial adenocarcinoma

There are two clinicopathological types of endometrial adenocarcinoma.

The first type is endometrioid adenocarcinoma and is usually due to unopposed oestrogenic stimulation and arises from endometrial intra-epithelial neoplasia (EIN). This type of tumour characteristically occurs in young women with the polycystic ovary syndrome or in association with obesity. It also affects peri-menopausal women, and may complicate post-menopausal oestrogen replacement therapy. It is generally associated with a good prognosis.

The second type of endometrial adenocarcinoma is non-endometrioid, affects elderly post-menopausal women, is not associated with oestrogenic stimulation, and probably arises on the basis of a pre-existing inactive or atrophic endometrium. High-grade serous and clear cell carcinoma are in this category and are associated with a poor prognosis.

Recently it has been shown that the molecular profiles of these two basic types of endometrial adenocarcinoma (endometrioid and non-endometrioid) are quite different (Table 19.4). The lack or presence of p53 mutation is the most important distinguishing molecular feature.

Table 19.4 Molecular profile of endometrial carcinoma

| Endometrioid | Serous | |

|---|---|---|

| ER/PR | + | – |

| p53 mutation | – | + |

| Microsatellite instability | ++ (20–30%) | + (11%) |

| PTEN mutation | + (34–83%) | – |

| k-ras mutation | + (10–30%) | – |

| Beta-catenin mutation | + (28–35%) | – |

Endometrial adenocarcinoma may be confined to the endometrium. Since the endometrium is composed of glands and stroma, it is possible for a carcinoma to invade its own stroma and still be intra-endometrial. Alternatively, there may be invasion of the myometrium (Fig. 19.16). The extent of myometrial invasion at the time of diagnosis is the single most important prognostic factor. Involvement of the endocervix also has an adverse effect on prognosis. Thereafter, spread of the tumour occurs via the lymphatic and venous routes to the vagina and pelvic and para-aortic lymph nodes.

Endometrial stromal sarcoma

Neoplastic change can occur in the endometrial stroma as well as the endometrial glands, but stromal neoplasms are much less common. Low-grade stromal sarcoma occurs in the uterus of peri- and post-menopausal women and may be diagnosed as an incidental finding in a hysterectomy specimen or following a clinical diagnosis of fibroids. Nodules of bland-looking stroma infiltrate the myometrium, with little or no mitotic activity. The natural history of these tumours is one of local recurrence, sometimes after many years. Histologically, these recurrences resemble the original tumour. High-grade uterine sarcoma is a highly malignant tumour which may show extensive invasion of the myometrium at the time of diagnosis, with high mitotic activity and focal necrosis.

Mixed Müllerian neoplasia

Not only do both glandular and stromal components of the endometrium have the propensity to undergo neoplastic change, but they may do so concurrently. This gives rise to the spectrum of mixed Müllerian (mesodermal) neoplasia. Either component may be benign or malignant. Several variants are recognised, but carcinosarcoma or malignant mixed Müllerian tumour is the most important type and is discussed in more detail below.

Malignant mixed Müllerian tumour (carcinosarcoma)

Malignant mixed Müllerian tumour is a highly malignant tumour with a poor prognosis that occurs in elderly women. Clinically, it presents in the same way as endometrial adenocarcinoma, but the tumour is usually advanced with extensive myometrial invasion at the time of diagnosis. Diagnosis can usually be made on an endometrial biopsy or curettage specimen, where obviously malignant glands and stroma are characterised by cellular pleomorphism, increased mitotic activity and abnormal mitoses. The tumours are usually polypoid and fill the endometrial cavity (Fig. 19.17). If the tumour shows only those components derived from endometrium or myometrium, it is of homologous type. Often, other components foreign to the uterus are seen, including cartilage and bone; it is then of heterologous type. Recent molecular genetic evidence suggests a monoclonal origin of these tumours, which should probably be regarded as ‘metaplastic carcinomas’.

ABNORMALITIES OF THE MYOMETRIUM

Adenomyosis

Adenomyosis is a common finding in hysterectomy specimens and refers to the presence of endometrial glands and stroma deep within the myometrium. It characteristically occurs in peri-menopausal multiparous women and is of uncertain aetiology. It may be regarded as a form of ‘diverticulosis’, as there is continuity between adenomyotic foci and the lining endometrium of the uterine cavity. Neoplastic change may occur within these foci but should not be regarded as evidence of myometrial invasion.

Smooth muscle tumours

The commonest tumour of the female genital tract is the benign fibroid or leiomyoma. These commonly present in later reproductive life and around the time of the menopause. They are associated with low parity, although it is uncertain whether this is a common cause or an effect. The precise aetiology of leiomyomas is unknown. They may present clinically with:

Characteristically, they are multiple, round, well-circumscribed tumours varying in diameter from 5 mm to, in some cases, 200mm or more (Fig. 19.18). They may show cystic change or focal necrosis. On section, they have a white, whorled appearance. Histologically, they are composed of complex interlacing bundles of smooth muscle fibres showing little or no mitotic activity. Sometimes, nodules of tumour may be seen within veins (intravenous leiomyomatosis); this is not a sinister feature. Smooth muscle tumours contain steroid hormone receptors, and at least a proportion are oestrogen-dependent.

Fig. 19.18 Benign fibroid or leiomyoma. Note the typical white whorled appearance of its cut surface. This is an enormous example, 160 mm in diameter; the remaining uterus is small by comparison.

The crucial factor in the assessment of malignancy in smooth muscle tumours is their mitotic activity. There is a very good correlation between clinical behaviour and the mitotic count but malignancy is always associated with other features, including nuclear pleomorphism, an irregular tumour margin, haemorrhage and necrosis. The mitotic count is usually expressed in terms of numbers of mitoses per 10 high-power fields (hpf) of the microscope (the field area should always be stated). Leiomyomas contain 0–3 mitoses/10 hpf. If there are 10 or more in association with nuclear pleomorphism, then a tumour must be regarded as a leiomyosarcoma and will behave as a malignant tumour, with all the risks of recurrence and metastases. If there are between 3 and 10 mitoses/10 hpf, the behaviour of smooth muscle tumours is unpredictable. They are referred to as ‘smooth muscle tumours of uncertain malignant potential’, and the patients must be placed under periodic surveillance. Although these criteria may appear arbitrary, their application has proved useful in practice.

OVARY

Ovarian lesions present either with pain due to inflammation or swelling of the organ, or with the remote effects of an endocrine secretion.

OVARIAN CYSTS

Ovarian cysts may be non-neoplastic or neoplastic; many ovarian tumours are partially cystic. The various types of non-neoplastic cyst are:

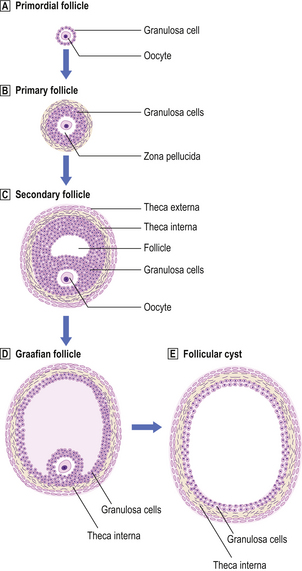

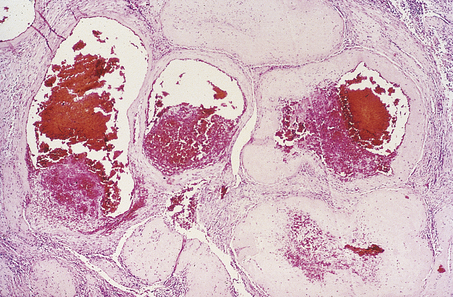

Inclusion cysts occur in the ovarian cortex probably as a result of surface trauma at the time of ovulation; they may be lined by original peritoneal mesothelium or metaplastic epithelium. This is discussed in more detail below. The nature and origin of many of the non-neoplastic cysts that occur in the ovary can only be appreciated with knowledge of the normal histology of the ovary, as well as of the development of the follicle (Fig. 19.19) and corpus luteum.

Fig. 19.19 Follicle development in the ovary and the origin of a follicular cyst.  Primordial follicle.

Primordial follicle.  Primary follicle. The primordial follicle responds to follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) to form a primary follicle comprising the oocyte, a mucopolysaccharide layer (zona pellucida) and proliferating granulosa cells.

Primary follicle. The primordial follicle responds to follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) to form a primary follicle comprising the oocyte, a mucopolysaccharide layer (zona pellucida) and proliferating granulosa cells.  and

and  Secondary and Graafian follicles. With continuing FSH stimulation a secondary or Graafian follicle is produced, comprising an eccentrically placed oocyte, a cavity containing clear liquid (the antrum), surrounding granulosa cells and condensed ovarian stromal cells, the theca interna and theca externa. The maximum diameter should be 25–30 mm.

Secondary and Graafian follicles. With continuing FSH stimulation a secondary or Graafian follicle is produced, comprising an eccentrically placed oocyte, a cavity containing clear liquid (the antrum), surrounding granulosa cells and condensed ovarian stromal cells, the theca interna and theca externa. The maximum diameter should be 25–30 mm.  Follicular cysts, which are probably due to disordered hormonal function, are larger than 30 mm.

Follicular cysts, which are probably due to disordered hormonal function, are larger than 30 mm.

Polycystic ovary syndrome

The polycystic ovary syndrome is the association of amenorrhoea, hyperoestrogenism and multiple follicular cysts of the ovary. There is usually stromal hyperplasia and little evidence that ovulation has occurred. The syndrome, which is related to defective insulin metabolism, is an important cause of infertility, endometrial hyperplasia and, rarely, endometrial adenocarcinoma in young women.

Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome

This may be induced by gonadotrophins or clomifene used in the treatment of infertility. It is characterised by bilateral ovarian enlargement due to multiple luteinised follicular cysts. The condition may be complicated by ascites and pericardial effusion, hypovolaemic shock and renal failure.

OVARIAN STROMAL HYPERPLASIA AND STROMAL LUTEINISATION

The stroma of the ovary is unlike stromal tissue at other sites because, in addition to a general metabolic and supportive function, the cells may also be directly involved in the endocrine activity of the organ. Ovarian stromal hyperplasia is a proliferative change seen to some extent in the ovaries of many peri- and post-menopausal women. It is characterised by the non-neoplastic proliferation of stromal cells resulting in varying degrees of bilateral ovarian enlargement. In old age there is a tendency towards atrophy. Atrophic ovaries tend to be small, wrinkled, hard and pearly white.

Hyperplastic ovarian stroma is associated with increased levels of androgens and oestrogens. Thus there is an association between stromal hyperplasia and endometrial hyperplasia, carcinoma and polyps. Other steroidogenic cells may be scattered throughout the stroma; such ‘luteinised’ cells may secrete androgens and may cause virilism. Stromal hyperplasia and luteinisation may also be observed in ovaries containing primary or secondary neoplasms.

ENDOMETRIOSIS

Endometriosis is the presence of endometrial glands and stroma in sites other than the uterine corpus. It is a very important cause of morbidity in women and may be responsible for pelvic inflammation, infertility and pain. The common sites include the pouch of Douglas, the pelvic peritoneum and the ovary. Endometriosis may also involve the serosal surface of the uterus, cervix, vulva and vagina, and extragenital sites such as the bladder and the small and large intestines. The occurrence of endometriosis in extra-abdominal sites is very rare.

The aetiology of endometriosis is unknown, but retrograde menstruation into the peritoneal cavity along the fallopian tube, and metaplasia of mesothelium to Müllerian-type epithelium, are possible explanations. The glands and stroma are usually subject to the same hormone-induced changes that occur in the endometrium. Thus, haemorrhage in endometriotic foci may cause pain. In the ovary especially, recurrent haemorrhage may produce cysts containing altered blood, so-called ‘chocolate cysts’. Uncommonly, hyperplastic or atypical changes may be seen in the epithelial component, with appearances similar to those that affect the endometrium. At least a proportion of endometrioid tumours of the ovary (see below) arise from pre-existing foci of endometriosis. Recently, similar patterns of chromosomal abnormalities (loss of heterozygosity) have been demonstrated in endometriosis and endometrioid adenocarcinoma. Individual endometriotic foci have been shown to be monoclonal.

OVARIAN NEOPLASMS

Ovarian tumours may be divided into five broad categories:

The further subdivisions of these categories are shown in Table 19.5.

Table 19.5 Classification of ovarian neoplasms

| Origin | Tumour | |

|---|---|---|

| Types | Subtypes | |

| Epithelium | Serous | |

| Mucinous | Benign, borderline or malignant | |

| Endometrioid∗ | ||

| Transitional cell | ||

| Germ cells | Dysgerminoma | |

| Teratoma | Mature cystic, immature solid or monodermal (e.g. carcinoid, struma ovarii) | |

| Extraembryonic | Yolk sac (endodermal sinus tumour), choriocarcinoma | |

| Malignant mixed germ cell tumours | ||

| Sex cord stroma | Thecoma | |

| Granulosa cell tumour | ||

| Sertoli–Leydig cell tumour | ||

| Mixed germ cell stromal tumour (gonadoblastoma) | ||

| Steroid cell tumour | ||

| Metastatic | Various (most commonly from the gastrointestinal tract) | |

| Miscellaneous | Haemangioma, lipoma, etc. | |

∗ Clear cell carcinoma is a variant of endometrioid tumour.

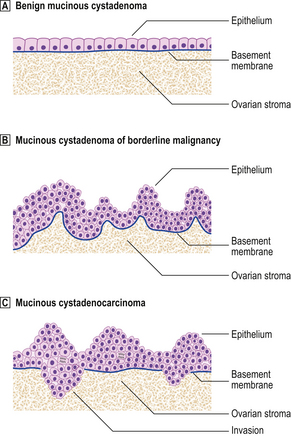

Epithelial tumours

Epithelial tumours are believed to arise from the mesothelial cell layer covering the peritoneal surface of the ovary and associated inclusion cysts. This mesothelium has the propensity to undergo metaplasia to Müllerian epithelium, as, indeed, does the entire mesothelial lining of the peritoneal cavity. Thus, differentiation may take place to resemble tubal mucosa (serous tumours), endocervical mucosa (mucinous tumours) or endometrium (endometrioid tumours). Transitional cell tumours do not fit neatly into this histogenetic theory as they resemble the transitional epithelium of the bladder. Each of these tumours may be benign or malignant (Fig. 19.20), but there is a third category of borderline tumour. These tumours show some of the features associated with malignancy, such as irregular architecture, nuclear stratification and pleomorphism and mitotic activity, but lack the most important criterion of invasion. Their biological behaviour is intermediate between that of clearly benign and overtly malignant tumours (Figs 19.21 and 19.22).

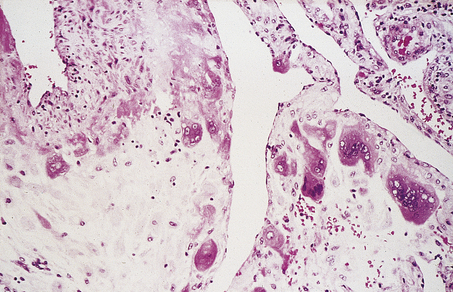

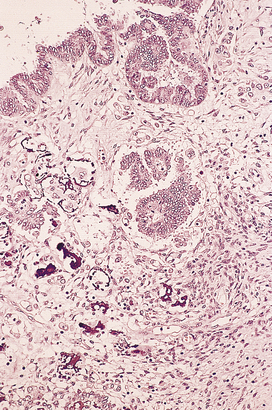

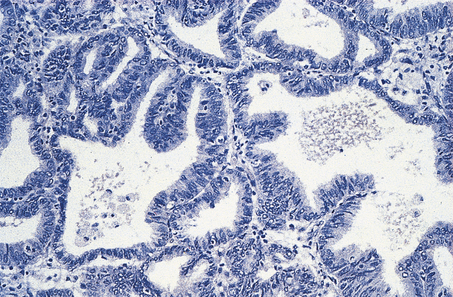

Fig. 19.20 Papillary serous adenocarcinoma. Note the presence of microcalcification (psammoma body formation).

Fig. 19.21 Epithelial morphology of ovarian mucinous neoplasms.  Benign mucinous cystadenoma. Note the monolayer of cuboidal mucinous cells and basally located nuclei.

Benign mucinous cystadenoma. Note the monolayer of cuboidal mucinous cells and basally located nuclei.  Mucinous cystadenoma of borderline malignancy. There is irregular architecture, multilayering of cells and mitotic activity, but the basement membrane is intact.

Mucinous cystadenoma of borderline malignancy. There is irregular architecture, multilayering of cells and mitotic activity, but the basement membrane is intact.  Mucinous cystadenocarcinoma. There is invasion through the original basement membrane.

Mucinous cystadenocarcinoma. There is invasion through the original basement membrane.

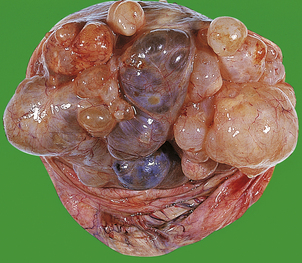

Fig. 19.22 Serous cystadenoma of borderline malignancy. An ovarian cyst containing abundant papillary tumour that was found on subsequent histological examination to be a serous borderline tumour.

Aneuploid tumours are more likely to behave in a malignant manner. A significant proportion of mucinous tumours, particularly in the borderline category, contain intestinal-type rather than endocervical-type epithelium. These tumours may be complicated by peritoneal implants producing copious amounts of mucus (pseudomyxoma peritonei). This condition has a poor prognosis and is often complicated by intestinal obstruction. However, recent evidence suggests that when pseudomyxoma peritonei is associated with appendiceal and ovarian disease, the peritoneal and ovarian lesions are, in fact, metastases from a primary appendiceal tumour.

The diagnosis of borderline tumour is made on the primary tumour but associated peritoneal implants may be borderline or invasive. The latter are associated with an adverse prognosis (60–70% 5-year survival).

Benign mucinous and serous tumours are commonly smooth-walled and cystic (Fig. 19.23), while benign transitional cell (Brenner) tumours are solid but may show cystic areas. Endometrioid tumours of the ovary may show the full range of mixed Müllerian neoplasia already referred to in the context of uterine tumours, such as endometrioid adenofibroma and carcinosarcoma.

The aetiology of epithelial ovarian cancer remains uncertain but certain facts are known. First, ovarian cancer is a disorder of developed societies and shows a higher incidence among women of higher social classes. Second, the oral contraceptive pill and pregnancy offer a protective effect; these probably act by reducing ovulation, although the reduced risk conferred by one pregnancy is much greater than would be expected. Thus, repeated ovulatory trauma to the surface epithelium seems to be a crucial factor.

Studies of ovarian cancer in families have shown that sisters and mothers of affected individuals have an approximately five-fold increased risk of ovarian cancer. Among all of the common cancers this is the largest excess risk to relatives and implies genetic susceptibility. Family studies also show that first-degree relatives are at an increased risk of breast cancer. Mutations of a rare dominant gene, BRCA1, localised on chromosome 17q, increase the risk of cancer at both sites. Familial ovarian cancer related to BRCA1 accounts for only 5–10% of ovarian cancers; they are predominantly of serous type. There is growing awareness that similar familial tumours can arise from the fallopian tube rather than the ovary.

Ovarian cancers show complex genetic abnormalities with a high incidence of p53 point mutations. Loss of heterozygosity has been demonstrated at a number of other chromosomal sites close to known tumour suppressor genes. Amplification of the erbB-2 (HER-2/neu) oncogene is associated with a poor prognosis.

Ovarian cancer is responsible for more deaths than any other gynaecological malignancy (Table 19.6). This is largely because it often presents at an advanced stage, due to its anatomically obscure site. Malignant tumours may be solid and/or cystic and there may be areas of haemorrhage and necrosis, with the tumour projecting into the lumen of a cyst or projecting exophytically into the peritoneal cavity. Tumour spread occurs predominantly intra-abdominally. The clinical staging of ovarian cancer is shown in Figure 19.24. The ovarian cancer-related protein CA125 is used routinely as a serum tumour marker, particularly to aid in the recognition of early relapse.

Table 19.6 Gynaecological cancer in the UK

| Cases∗ | Deaths† | |

|---|---|---|

| Ovary | 6615 | 4447 |

| Uterus | 6438 | 1637 |

| Cervix | 2726 | 1061 |

| Vulva | 1022 | 332 |

| Vagina | 246 | 107 |

Data from Cancer Research UK (http://info.cancerresearchuk.org/cancerstats)

Germ cell tumours

A potentially confusing range of tumours may arise from germ cells in the ovary. These may be benign or malignant.

Dysgerminoma

The fundamental or undifferentiated female ovarian germ cell tumour is the dysgerminoma, which is the exact counterpart of the seminoma arising in the male testis. It is a rare malignant tumour arising predominantly in young females; it is usually confined to one ovary and has a fleshy cut surface. Histologically, it shows a uniform appearance of germ cells admixed with lymphocytes. Occasional giant cells containing human chorionic gonadotrophin may be present, but these do not imply a poorer prognosis. These tumours are highly radiosensitive.

Teratomas

When germ cells differentiate along embryonic lines they give rise to teratomas, that is, a tumour that contains elements of all three germ cell layers—ectoderm, endoderm and mesoderm.

Mature cystic teratoma

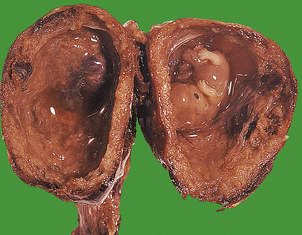

The commonest germ cell tumour and, indeed, the commonest ovarian tumour, is the benign or mature cystic teratoma (dermoid cyst). The majority of ovarian mature cystic teratomas arise from an oocyte that has completed the first meiotic division, in a manner analogous to parthenogenesis. It may present at any age, although usually in younger patients, as a smooth-walled, unilateral ovarian cyst. These tumours characteristically contain hair, sebaceous material and teeth (Fig. 19.25). Histologically, they show a wide range of tissues which, although haphazardly arranged, are indistinguishable from those seen in the normal adult. Squamous epithelium, bronchial epithelium, cartilage and intestinal epithelium may all be seen. These tumours are benign, although in elderly women malignancy (usually squamous carcinoma) may develop very rarely.

Immature teratoma

In contrast to the mature cystic type, teratomas may also be predominantly solid and composed of immature tissues similar to those seen in the developing embryo. These tumours are potentially malignant, and the predominant components are immature neural tissue and immature mesenchyme. They occur in young patients, and the prognosis is related to the amount of immature neural tissue present. Such tumours may metastasise to the peritoneum, where the assessment of tissue maturity is crucial, particularly in assessing response to chemotherapy. Immature neural tissue within the peritoneum may mature, or mature glial tissue may be present from the outset (gliomatosis peritonei).

Monodermal teratoma

Germ cell tumours may be composed entirely, or almost entirely, of tissue derived from one germ cell layer; these are monodermal teratomas. The best known examples are struma ovarii, composed of thyroid tissue which may be benign or malignant and rarely cause thyrotoxicosis, and carcinoid tumours, which are similar to carcinoid tumours arising in the gut. The carcinoid syndrome may occur even with benign tumours, as metabolic products are released directly into the systemic circulation and are therefore not denatured by hepatic enzymes.

Extra-embryonic germ cell tumours

Differentiation of germ cells may take place along extra-embryonic (as opposed to embryonic) lines to form the neoplastic counterparts of the non-fetal parts of the conceptus (the primitive yolk sac and the trophoblast of the placenta). These elements may give rise to yolk sac tumours (also known as endodermal sinus tumours because of their resemblance to the endodermal sinuses of Duval in the developing rat placenta) and choriocarcinoma. These are highly malignant tumours which may be associated with other germ cell elements.

Yolk sac tumours

Yolk sac tumours usually affect young females below the age of 30 years. The tumours are cystic and solid and often haemorrhagic. Histologically, characteristic structures (Duval–Schiller bodies), composed of central vessels with a rosette of tumour cells, may be seen. Alpha-fetoprotein may be demonstrated immunohistochemically and is used as a serum marker. Intra-abdominal metastasis occurs, and the prognosis for untreated patients is poor. Modern combination chemotherapy, however, has considerably improved the outlook for patients with this tumour, and subsequent pregnancy following conservative surgery and chemotherapy is now possible.

Choriocarcinoma

Pure choriocarcinoma of the ovary is extremely rare and is associated with beta human chorionic gonadotrophin production. Theoretically, it could occur either as a germ cell tumour or as a primary or secondary gestational neoplasm (see below), in which case the tumour would contain the paternal haplotype on chromosomal analysis. When choriocarcinoma is seen, it is more usually one component of a malignant mixed germ cell tumour.

Sex cord-stromal tumours

During the fourth month of fetal life and onwards cell cords grow down from the surface epithelium of the ovary to surround the primordial follicles. Sex cord-stromal tumours comprise a range of ovarian neoplasms which frequently produce steroid hormones and are considered to arise from the cells that are the adult derivatives of these primitive sex cords in the fetal ovary. The detailed classification of these tumours is complex, but there are five broad groups (see Table 19.5).

Thecoma

Thecoma is the commonest sex cord-stromal tumour. It presents in the reproductive years as an abdominal mass, and is a benign tumour of the ovarian stroma. It is usually unilateral and well-circumscribed with a pale, fleshy cut surface. Histologically, it is a cellular, spindle-celled tumour containing abundant lipid. Its particular importance clinically is that it may be associated with the production of oestrogens.

Granulosa cell tumour

Granulosa cell tumour can occur at any age and all cases are potentially malignant, although there is a close correlation between large size at presentation and malignant behaviour. It is particularly associated with oestrogenic manifestations, and may therefore give rise to abnormal uterine bleeding, endometrial hyperplasia or, uncommonly, endometrial adenocarcinoma. (It should, however, be remembered that granulosa cells do not synthesise oestrogens, but merely convert hormonal precursors to oestrogens.) They present as unilateral multicystic tumours that may be focally haemorrhagic or necrotic. Histologically, they are composed of nests and cords of granulosa cells with characteristically grooved nuclei. Often, cells surround a central space containing eosinophilic hyaline material; this structure is called the Call–Exner body. Granulosa cell tumours are characterised by their propensity for late recurrence, in some cases many years after removal of the original tumour. Granulosa cells produce inhibin which is used as a serum or immunohistochemical marker for the tumour.

Sertoli–Leydig cell tumours

Sertoli–Leydig cell tumours are rare tumours composed of a variable mixture of cell types normally seen in the testis. Pure Sertoli and Leydig cell tumours may also occur. The tumours may be well, moderately or poorly differentiated and may present with androgenic signs and symptoms. Leydig cells may be identified by the presence of Reinke’s crystals within their cytoplasm.

Gonadoblastoma

Gonadoblastoma is a rare lesion, which may not be a true neoplasm, in which primitive germ cells and sex cord-stromal derivatives are present. The latter usually resemble immature Sertoli cells and granulosa cells. These lesions typically develop in the dysgenetic streak gonads of phenotypic females carrying a Y chromosome. The germ cell component may undergo malignant change, usually to form a dysgerminoma.

Steroid cell tumours

Steroid cell tumours are uncommon and are usually benign and unilateral. In many cases the patient presents with virilisation due to androgen production (Fig. 19.26). Microscopically, the tumour is well circumscribed and composed of cells that resemble adrenal cortical cells and contain abundant intracellular lipid. The precise origin of these tumours is still debated. Although other sex cord-stromal tumours may secrete steroids, the term ‘steroid cell tumour’ is conventionally reserved for this particular variant.

Metastatic tumours

Tumour metastatic to the ovary may be genital or extragenital. Endometrial adenocarcinoma may spread to the ovary, but it should be remembered that primary endometrial adenocarcinoma may co-exist with primary endometrioid adenocarcinoma of the ovary and be associated with a favourable prognosis. Large intestine, stomach and breast adenocarcinomas are the most important extragenital tumours. Metastatic colonic adenocarcinoma may be confused with primary mucinous cystadenocarcinoma or endometrioid adenocarcinoma. The term ‘Krukenberg tumour’ refers to bilateral ovarian neoplasms composed of malignant, mucin-containing, signet-ring cells, usually of gastric origin. Breast carcinoma frequently metastasises to the ovary, but usually these metastases do not manifest themselves clinically. Metastatic malignant melanoma may first present as an ovarian tumour.

FALLOPIAN TUBES

The fallopian tubes may be the site of inflammation, pregnancy, cysts or neoplasia. Inflammatory lesions and tubal ectopic pregnancies commonly present clinically with acute lower abdominal pain, mimicking, for example, acute appendicitis. Loss of tubal patency is an important cause of female infertility.

Inflammation (salpingitis)

Inflammation of the fallopian tube (salpingitis) is usually secondary to endometrial infection or the presence of an intra-uterine device; it may be acute or chronic. Chlamydial infection is now an important cause of chronic inflammation and subsequent secondary infertility due to loss of tubal patency. Anaerobic organisms, such as Bacteroides, are also important as causes of salpingitis, whereas gonococcal infection is uncommon. Infection may be complicated by the accumulation of pus within the lumen of the tube (pyosalpinx). Longstanding chronic inflammation may lead to distension of the tube, loss of mucosa and the accumulation of serous fluid within the lumen (hydrosalpinx).

Cysts and tumours

Benign fimbrial cysts and paratubal cysts are common. They are usually lined by tubal-type epithelium. Rarely, benign papillary serous neoplasms may arise in paratubal or para-ovarian cysts.

Tumours of the fallopian tube are uncommon. Of most clinical importance is primary adenocarcinoma of the fallopian tube epithelium which, in some cases, may have a familial basis related to inherited BRCA1 mutation. This tumour has a similar appearance to that of papillary serous adenocarcinoma of the ovary, for which it may be mistaken. The mode of spread is via lymphatics and the peritoneum. The tumour usually has a poor prognosis.

PATHOLOGY OF PREGNANCY

There is a high rate of fetal loss in early pregnancy, and many early miscarriages are subclinical. Clinical miscarriage is usually the result of chromosomal abnormalities (Ch. 3). The chorionic villi of the immature placenta may be oedematous (hydropic change), or the stroma may be fibrotic, which is an involutional change following fetal death.

HYDATIDIFORM MOLE

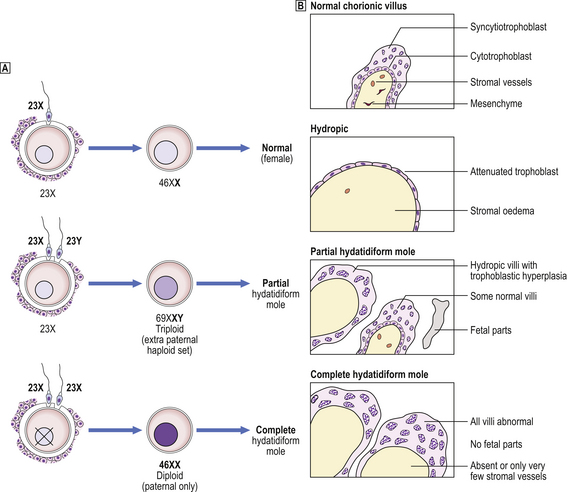

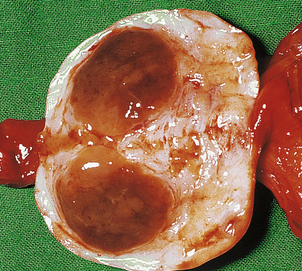

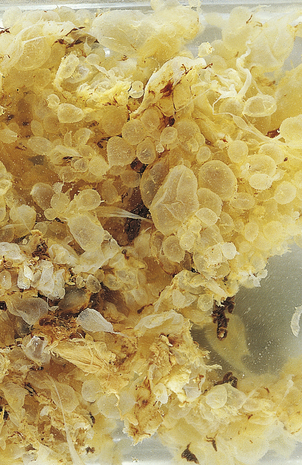

Hydatidiform mole is a disorder of pregnancy affecting approximately 1 in 1000 pregnancies in the Western world and is much commoner in the Far East. It is characterised by swollen, oedematous chorionic villi, trophoblastic hyperplasia and the irregular distribution of villous trophoblast. Macroscopically, the placenta appears to be composed of multiple cystic, ‘grape-like’ structures (Fig. 19.27). A hydatidiform mole usually grows faster than a normal pregnancy, and the patient may present either with a ‘large for dates’ pregnant uterus, or with bleeding in early pregnancy. If an ultrasound scan is performed, the abnormal cysts can be clearly seen and uterine evacuation is indicated. There are two types of hydatidiform mole—complete mole and partial mole (Fig. 19.28)—which are genetically quite different.

Fig. 19.28 Hydatidiform mole.  Genetic analysis. Partial moles are triploid and result from fertilisation of one ovum by two spermatozoa. Complete moles are diploid, but comprise only paternal chromosomes.

Genetic analysis. Partial moles are triploid and result from fertilisation of one ovum by two spermatozoa. Complete moles are diploid, but comprise only paternal chromosomes.  Morphology. See text for details.

Morphology. See text for details.

Partial mole

The partial mole is triploid, and may not be diagnosed clinically but only identified histologically in miscarriage material. Most contain one maternal and two paternal haploid sets of chromosomes, with all three sex chromosome patterns possible (XXY, XXX and XYY). It must be remembered, however, that not all triploids are partial moles. A fetus may be present and only a proportion of the villi are abnormal; the rest may be fibrotic or may simply be hydropic without trophoblastic hyperplasia. Stromal vessels are present.

Complete mole

The chromosomal constitution of the complete mole is androgenetic (i.e. of paternal origin), characteristically 46XX, and is probably due to the fertilisation of an anucleate ovum either by a spermatozoon carrying an X chromosome which is then replicated or by two X-bearing spermatozoa. Grossly, the placenta is obviously abnormal with swollen villi. Histologically, the oedema is confirmed; there is an absence of stromal vessels and circumferential trophoblastic hyperplasia affecting all villi. The constituent trophoblast may show varying degrees of cytological atypia.

p57kip2

p57kip2 is a maternally expressed imprinted gene. Its protein product is expressed by the villous cytotrophoblast of partial moles but not androgenetic complete moles.

Complications

The importance of correctly diagnosing hydatidiform mole is that, in a small number of cases, the disorder may be complicated by gestational trophoblastic neoplasia (persistent trophoblastic disease). This term encompasses two main pathological entities with similar clinical manifestations, diagnosed by persistently elevated or rising urinary hCG levels following evacuation of molar tissue.

Cases of hydatidiform mole are monitored by estimation of the serum and urinary hCG. If the level rises, or does not fall, then the patient will receive chemotherapy irrespective of the precise pathological diagnosis. The role of the pathologist in the management of gestational trophoblastic neoplasia is thus limited. The neoplastic potential of complete mole is greater than that of partial mole. Therefore, all cases of molar disease are followed up, although this may prove to be unnecessary in many cases. Patients are advised not to become pregnant during follow-up as this would cause a confusing rise in hCG levels.

PATHOLOGY OF THE FULL-TERM PLACENTA

The pathology of the full-term placenta is a large complex topic, the details of which are beyond the scope of this book. Only the commoner and/or clinically significant lesions are mentioned here. These may be considered under the following headings:

Fascinatingly, long-term follow-up of offspring whose placental weights were accurately recorded in the early to mid 20th century has shown a strong correlation between low placental weight and subsequent adult (e.g. cardiovascular) disease.

Abnormalities of placentation

Abnormalities of placental shape are usually of no clinical significance. Placenta accreta is an abnormality of implantation.

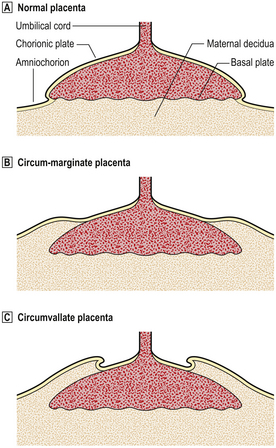

Extrachorial placentation

Extrachorial placentation is a developmental abnormality in which the fetal surface of the placenta from which the chorionic villi arise (the chorionic plate) is smaller than the maternal surface attached to the uterine decidua (the basal plate). Thus, the border between the extravillous chorionic membrane and chorionic villi is not at the placental margin but is present circumferentially on the fetal surface of the placenta (Fig. 19.29). This border may be flat (‘circum-marginate’) or raised (‘circumvallate’). Circum-marginate placentation is of no clinical significance, but circumvallate placentation is associated with a higher incidence of low birthweight babies, although the causal relationship between the two is still obscure.

Accessory lobe

An accessory lobe to the placenta is usually of no clinical importance, but occasionally the lobe may be retained in utero after delivery of the main placenta.

Placenta accreta

Placenta accreta is a rare disorder in which the chorionic villi are immediately adjacent to, or penetrate, the myometrium to a varying degree. This is associated with a deficiency of decidua, and may be the result of previous operative intervention, such as curettage or caesarean section, infection or uterine malformation. The main clinical significance is the risk of ante-partum bleeding. Post-partum bleeding may also occur due to a failure of placental separation resulting from the abnormally adherent chorionic villi.

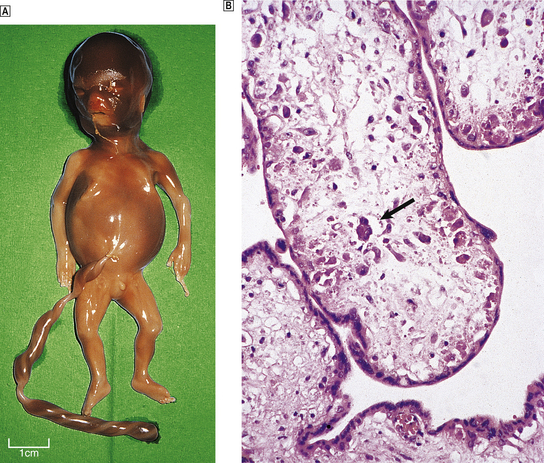

Inflammation

Inflammation of the placental tissues may involve either the chorionic villi (villitis) or the extraplacental membranes (chorioamnionitis). Inflammation of chorionic villi is usually due to infection through the maternal blood stream. Specific infections, such as listeriosis, toxoplasmosis or cytomegalovirus, are responsible for only a small proportion of cases (Fig. 19.30). Most examples are of unknown aetiology, and are seen in approximately 5% of all pregnancies as a focal infiltrate of lymphocytes and histiocytes. Villitis is associated with an increased incidence of fetal intra-uterine growth retardation but, again, the pathogenesis is unclear.

Vascular lesions

Several vascular lesions may occur in the placenta. They are usually of no clinical significance.

Perivillous fibrin deposition

Perivillous fibrin deposition occurs to some extent in all placentae and quite commonly is macroscopically apparent as a firm white plaque. The lesion is of no clinical significance.

Fetal artery thrombosis

Thrombosis of a fetal villous stem artery will produce a well-circumscribed area of avascular chorionic villi, which may be apparent macroscopically as an area of pallor. The inter-villous space appears normal. The aetiology is unknown, although there is an association with maternal diabetes mellitus. Although usually of no clinical significance, extensive thrombosis of fetal villous stem vessels can, rarely, be responsible for fetal death.

Placental infarct

A placental infarct is a localised area of ischaemic villous necrosis due to thrombotic occlusion of a maternal uteroplacental (spiral) artery. (It must be remembered that chorionic villi have a dual blood supply.) Macroscopically, fresh infarcts are red but progressively undergo fibrosis. When extensive, placental infarction is a manifestation of maternal vascular disease and is thus particularly associated with hypertensive disorders of pregnancy.

Haemangioma

Haemangiomas are uncommon tumours that occur as well-circumscribed, dark nodules. They are of no clinical significance except when large or multiple. They may then be associated with polyhydramnios, premature labour and intra-uterine growth retardation due to diversion of blood through the tumour rather than through normal placental tissue.

Immaturity of villous development