33 Genetic Counseling in Congenital Heart Defects

I. INTRODUCTION

B. Counseling for congenital heart diseases

a. Obtain a family history and pregnancy history.

b. Discuss the fetal ultrasound findings.

d. Discuss the options available.

2. Throughout this process, the family should be made to feel secure that they will be supported by the health care professionals involved in their care, regardless of any decision they make.

II. THE PROCESS OF COUNSELING

A. Obtaining a family history

1. A three-generation family history should be obtained that contains critical medical data and biological relationships.

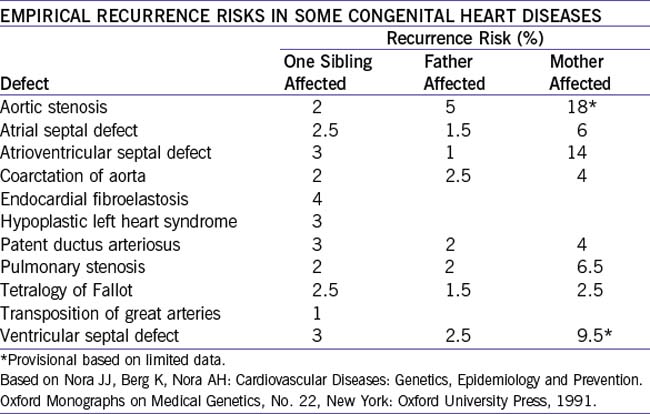

2. The risk is much greater if it is the mother rather than the father who has the heart defect.

3. Information regarding family members with congenital abnormalities, recurrent miscarriages, stillbirths, mental retardation, inherited conditions, and consanguinity should be recorded.

4. The family pedigree is a tool for:

a. Making a medical diagnosis.

b. Deciding on testing strategies.

c. Establishing the pattern of inheritance.

d. Identifying at-risk family members.

f. Determining reproductive options.

g. Distinguishing genetic from other risk factors.

h. Making decisions on medical management and surveillance.

i. Developing patient rapport.

j. Educating the patient and exploring the patient’s understanding.

C. Discussing the cardiac abnormalities

1. The cardiac abnormalities should be discussed in the context of the other abnormalities detected in the fetus or newborn. For example, the cardiac abnormality may be minor, and yet the overall prognosis can be grim because of major brain abnormalities.

2. In cases with isolated cardiac abnormality or when the extracardiac abnormalities are minimal, the information regarding the prognosis and the surgical procedures should be provided mainly by the cardiologist.

3. When multiple abnormalities are detected or a specific condition is detected, the counseling should be given by a multidisciplinary group that includes everyone involved in the child’s care.

D. Providing support

1. The diagnosis of a fetal or newborn cardiac abnormality can be a time of crisis for the family.

2. The crisis can be exacerbated by not being able to secure an accurate diagnosis or by the unpredictability of the findings and prognosis.

3. This crisis can lead to a feeling of loss of control for the family.

4. Providers of genetic counseling should bear this in mind, and the session should be tailored to support the personal interests, beliefs, and coping mechanisms of the family.

III. ETIOLOGIC CATEGORIES IN CONGENITAL HEART DISEASES

A. Incidence

1. The majority of isolated cardiac abnormalities are multifactorial (85%).

2. Chromosome abnormalities are associated with 8% to 10%.

3. Single-gene disorders are found in 3% to 5% (Table 33-1).

TABLE 33-1 ETIOLOGIC DISTRIBUTION OF CONGENITAL HEART DISEASE

| Etiology | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Multifactorial | 85% |

| Chromosome abnormalities | 8–10% |

| Single gene disorders | 3–5% |

| Maternal disease (IDDM, PKU, SLE etc.) | 1% |

| Maternal exposures (infections, teratogens etc.) | 1% |

B. Mode of inheritance

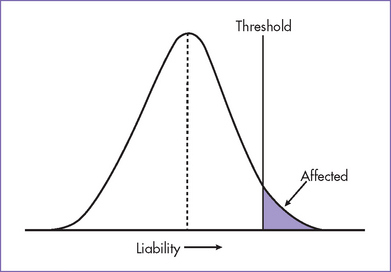

1. Multifactorial inheritance (Fig. 33-1).

a. Multifactorial inheritance is the result of interactions of many genes (genes on different chromosomes and involved in a certain function) and environmental factors.

b. The sum of the genetic and environmental contribution determines the person’s liability to develop a disorder.

c. This liability has a bell-shaped curve in the general population, where most of the population is in the mean and unaffected, and a small portion of the population past the threshold and expresses the clinical manifestations.

d. This mode of inheritance is the most common cause of genetic disorders and is responsible for the greatest number of patients who will need special care or hospitalization because of genetic diseases, including congenital heart disease.

e. Up to 10% of newborn children express a multifactorial disease at some time in their lives, such as atopic reactions, diabetes, cancer, spina bifida, anencephaly, pyloric stenosis, cleft lip, cleft palate, congenital hip dysplasia, club foot, and congenital heart disease, among others. Some of these diseases occur more frequently in female patients (scoliosis, congenital dislocation of the hips) and some are more common in male patients (pyloric stenosis).

f. Hallmarks for multifactorial inheritance.

. Thus, the lower the incidence of a condition in the population, the greater the relative increased risk for siblings (e.g., cleft lip). Environmental factors as well as genetic factors are involved.

. Thus, the lower the incidence of a condition in the population, the greater the relative increased risk for siblings (e.g., cleft lip). Environmental factors as well as genetic factors are involved.g. Empirical risk for some congenital cardiac abnormalities is outlined in Table 33-2.

a. Chromosome abnormalities are detected in about 10% of newborns with congenital heart disease (Ferencz et al, 1989).

b. The incidence in fetuses with prenatally diagnosed congenital heart disease is most probably threefold higher (Berg et al, 1988).

c. Because specific congenital heart diseases are known to be associated with certain chromosome abnormalities, we can assume that the gene or genes associated with these abnormalities must have a major role in cardiac development (Table 33-3).

d. This is emphasized in contiguous-gene disorders where a specific gene known to have a major role in the development of the heart is deleted and results in specific cardiac abnormalities (Table 33-4).

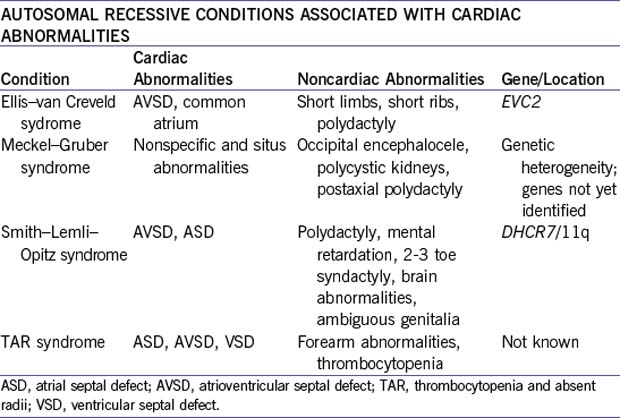

a. Autosomal recessive inheritance and conditions.

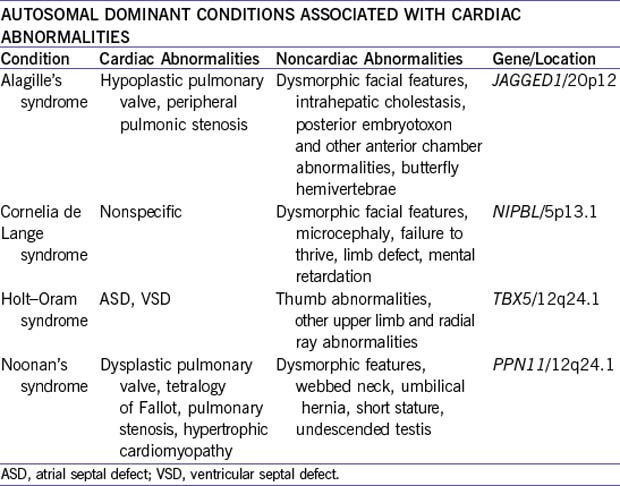

b. Autosomal dominant inheritance and conditions.

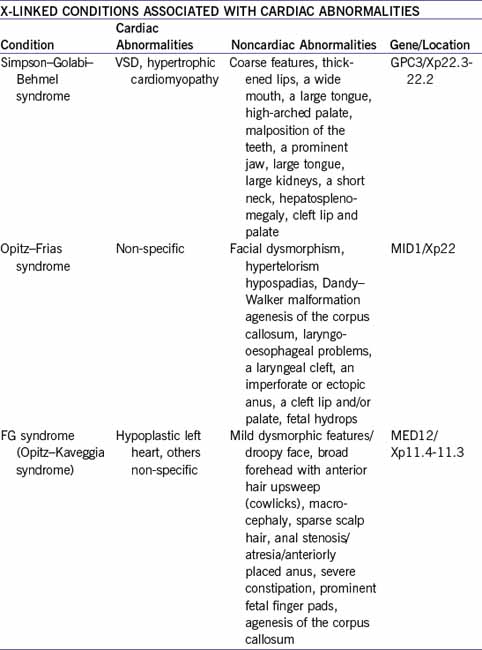

c. X-linked inheritance and conditions

Fig. 33-1 Model of multifactorial inheritance in common disorders including congenital heart disease.

TABLE 33-3 CONGENITAL HEART DISEASE AND SYNDROMES ASSOCIATED WITH CHROMOSOME ABNORMALITIES

| Chromosome Abnormality | Cardiac Abnormalities | % with CHD |

|---|---|---|

| Trisomy 18 | VSD, dysplastic valves | 100 |

| Trisomy 13 | VSD, DORV, tetralogy of Fallot, transposition of great arteries | 80 |

| Trisomy 21 | AVSD | 40 |

| Trisomy or tetrasomy 22p (cat eye syndrome) | TAPVC | 40 |

| 45, X | Bicuspid aortic valve, coarctation of aorta, HLHS | 35 |

| 18q- | Heterotaxia, nonspecific | 20 |

AVSD, atrioventricular septal defect; CHD, congenital heart disease; DORV, double-outlet right ventricle; HLHS, hypoplastic left heart syndrome; TAPVC, total anomalous pulmonary venous connection; VSD, ventricular septal defect.

TABLE 33-4 CONTIGUOUS GENE DISORDERS ASSOCIATED WITH CONGENITAL HEART DISEASE

| Condition | Cardiac Abnormalities | Chromosome Deletion |

|---|---|---|

| Miller–Dieker syndrome | Miscellaneous | del(17p13.3) |

| Velocardiofacial syndrome | Ventricular septal defect, tetralogy of Fallot | del(22q11.2) |

| Williams’ syndrome | Supravalvar aortic stenosis, supravalvar pulmonic stenosis | del (7q11.2) |

The X-linked condition can be the result of a new mutation in the X chromosome in the egg or sperm. When the new mutation happens in the egg, the male carrying this mutation will be affected and the females will usually be carriers and unaffected. If the new mutation occur in the sperm, only females will inherit this X chromosome and will usually be carriers and unaffected. These females will have a 25% risk for having an affected son in each of their pregnancies. Relatively common CHD with autosomal dominant inheritance are listed in Table 33-7.

IV. MATERNAL EXPOSURES AND DISEASES

For an expanded discussion of maternal exposures and diseases, see Chapter 2.

A. Exposures

1. Exposure to teratogens during embryogenesis can result in a specific pattern of abnormalities that can also involve the heart.

b. Peripheral pulmonary artery stenosis.

c. Pulmonary valve stenosis (less common).

3. Exposure to alcohol results in miscellaneous congenital heart disease in 40% of patients.

4. Exposure to retinoic acid results in congenital heart disease in 25% of patients.

B. Diseases

1. Uncontrolled maternal insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus results in congenital heart disease in 5% to 8% of patients.

2. The most common cardiac abnormalities are ventricular septal defect (VSD) and TGA.

3. Untreated maternal phenylketonuria (PKU) results in congenital heart disease in 15% to 20% of the cases. The most common cardiac abnormalities are VSD, atrial septal defect (ASD), patent ductus arteriosus, and TOF.

V. DISCUSSING THE OPTIONS AVAILABLE

A. Informed choice

1. There is a growing tendency to consider informed choice as being based on relevant knowledge consistent with the decision maker’s values and as being behaviorally implemented.

2. Once the cardiac and noncardiac abnormalities are identified, an attempt should be made to identify the etiology (if possible) and thus the risks to future pregnancies so that the mother or couple can make informed decisions.

B. Making the decision

1. After discussing the findings and the risks, if available, the family may choose the treatment.

2. In rare severe cases, the family might decide not to provide any treatment and, in prenatally diagnosed cases, might decide to terminate the pregnancy.

3. Regardless of the decision the family makes, they should be made to feel secure that they will be supported by all counselors and responsible caregivers involved.

4. Often, a family has difficulties with reaching a decision, especially when there is limited time. In this case it is our role to help in the decision-making process by exploring what the outcome of each decision would be in the context of the family’s belief systems.

VI. SPECIFIC ANOMALIES AND SYNDROMES

A. Ventricular septal defect

1. VSDs are the commonest form of congenital heart disease detected in infancy and account for more than 30% of the total cases of congenital heart disease. The incidence is 2 in 1000 live births.

2. The risk to the offspring seems to be higher (about 9.5%) if the mother is affected. The concordance rate with VSD recurring in first-degree relatives varies from 30% to 60%.

3. The most common discordant lesion in humans is ventricular septal defect followed by pulmonary stenosis, TGA, and tricuspid atresia.

B. Atrial septal defect

1. The vast majority of ASDs follow a multifactorial inheritance. Some families show autosomal dominant inheritance (one form has been mapped to chromosome 1).

2. ASD is also part of the autosomal dominant syndrome associations such as Holt–Oram syndrome, cases of familial Noonan’s syndrome, and ASD with atrioventricular conduction defects.

3. Concordance in siblings and first-degree relatives of patients with an ASD is about 50% in combined series.

C. Hypoplastic left heart syndrome

1. The spectrum of left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) obstruction consists of hypoplastic left heart or left ventricle, aortic valve stenosis, bicuspid aortic valve, hypoplastic aortic arch, and coarctation of the aorta.

2. The overall recurrence risk is about 3.2%. This is higher than what is predicted for multifactorial inheritance alone.

3. Only about 25% of recurrence involves hypoplastic left heart syndrome; the remainder includes other cardiac anomalies including VSD and ASD.

4. In the case of parental consanguinity or in families with two or more affected children, autosomal recessive inheritance should be considered.

D. Pulmonary stenosis

1. About 10% of patients with pulmonary stenosis have Noonan’s syndrome. This disorder is an autosomal dominant dysmorphic syndrome characterized by short stature and congenital heart diseases.

2. If Noonan’s syndrome is suspected in a patient with pulmonary stenosis, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and other left-sided heart lesions should be sought.

3. Many patients have no family history, but there are many cases of autosomal dominant inheritance, and in those cases the risk to the offspring is 50%. One gene locus has been assigned to chromosome 12q22, and mutations in the SHP2 gene have been identified in some patients.

1. Velocardiofacial syndrome (VCFS) or DiGeorge’s syndrome.

a. Patients with VCFS (also called Shprintzen’s syndrome) have a wide range of phenotypic abnormalities including short stature, velopharyngeal incompetence and hypernasal speech, cardiac anomalies (in 75%-80% of patients), typical facies, and learning disabilities. Hypernasal speech is often the finding that brings these children to attention.

b. In classic DiGeorge’s syndrome, thymic aplasia and hypocalcemia complicate the picture.

c. Evidence suggests that VCFS and DiGeorge’s syndrome might result from mutations in the same genes. Mutations in the TBX1 gene have been identified in patients with VCFS.

d. Cardiac malformations are mainly conotruncal abnormalities, but other lesions, such as TGA and TOF, do occur.

e. Male-to-male transmission established autosomal dominant inheritance, and most patients represent new mutations on the basis of microdeletion of chromosome 22q11. Inherited deletions occur in 25% to 30% of patients. A second gene locus is located on chromosome 10.

f. The microdeletions are rarely visible by conventional cytogenic analysis.

g. The disorder can be detected by fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH).

h. FISH analysis has become a routine diagnostic tool in both prenatal and postnatal diagnosis.

a. Williams’ syndrome is an autosomal dominant disorder characterized by elfin face, mental and statural deficiency, characteristic dental malformation, infantile hypercalcemia, and congenital heart disease. The cardiovascular malformations include supravalvar aortic stenosis, multiple peripheral pulmonary artery stenosis, pulmonary valve stenosis, and VSD.

b. Other arterial anomalies, such as renal anomalies, are also common.

c. Most patients represent sporadic cases within otherwise normal families. Parent-to-child transmission is not common.

d. Both inherited and sporadic cases are caused by a small deletion including the elastin gene located within chromosome 7q11. This microdeletion can be deselected by FISH.

VII. HETEROTAXY SYNDROME

A. Overview

1. A number of names are used to describe this condition: isomerism sequence, asplenia syndrome, Ivemark’s syndrome, polysplenia syndrome, situs ambiguous, heterotaxia, partial situs inversus, and laterality sequence.

2. The severity of the condition depends on the type of isomerism, the associated structural and conductive cardiac defect, and the extracardiac abnormalities.

D. Recurrence risk

1. Most cases of laterality disturbance are sporadic, although some of the cases are inherited.

a. Inheritance is mainly autosomal recessive, such as the one caused by DNAI1 gene mutation.

b. Some inheritance is X linked, such as the one caused by ZIC3 gene mutation.

2. In a sporadic case, the recurrence risk is about 5%.

3. In autosomal recessive cases, the recurrence risk is 5%.

4. In familial X-linked cases, each of the mother’s daughters has a 50% chance of being a carrier, and each of her sons has a 50% chance of being affected. Because female carriers have no abnormalities, in most cases, a female carrier can only be detected by mutation analysis if the gene is known.

5. In a sporadic case where an X-linked condition is suspected but not proved by mutation analysis, the only prenatal tool available is fetal ultrasound and fetal echocardiography.

6. The incidence of chromosome abnormalities, including deletion of 22q11.2 in cases with laterality disorder, is low. However, cases with deletion at 22q11, 18p-, and 7q- associated with laterality disorder have been reported.

VIII. TBX5 GENE

A. Genetics

1. The TBX5 gene belongs to the Drosophila optomotor-blind (omb) gene family and the murine brachyury or T gene.

2. Members of the T-box gene family act as transcription factors, and the conserved T-box domain serves as a DNA-binding domain that codes for a DNA-binding protein.

3. These genes share a common DNA-binding motif (T-box). The TBX5 gene was named in line with their mouse homologue, contains 9 exons, spans more than 47 kb, and was mapped to 12q24.1.

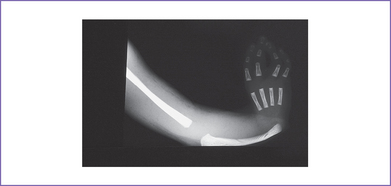

4. The TBX5 gene has a role in forelimb and heart development, and a mutation in this gene results in Holt–Oram syndrome (Figs. 33-2 and 33-3).

B. Characteristics

1. Holt–Oram syndrome is characterized by upper-extremity malformations involving radial, thenar, or carpal bones.

2. The most common malformations are thumb abnormalities, including digitalized, absent, hypoplastic, triphalangeal or (rarely) bifid thumbs. The other fingers might be involved as well.

3. The other major component of Holt–Oram syndrome is heart abnormality; 75% of patients with Holt–Oram syndrome have a congenital heart malformation.

4. The patient typically has a personal and/or family history of congenital heart malformation, predominantly ostium secundum ASD or, more rarely, a VSD, but other lesions have also occurred, including HLHS and cardiac conduction disease.

IX. INVASIVE PRENATAL TESTING

A. Chromosomal anomalies and heart disease

1. Fetal cardiac disease and extracardiac abnormalities (mainly of the central nervous, gastrointestinal, and genitourinary systems) are strongly associated with aneuploidies (Allan et al, 2004).

2. The incidence of chromosomal abnormalities in fetuses with congenital heart disease ranges from 17% to 48% (Allan et al, 2004; Paladini et al, 1993; Raymond et al, 1997; Touati et al, 1988), but only 5% to 10% of infants with congenital heart disease have a chromosomal abnormality (Yates et al, 1996).

3. Extracardiac abnormalities are more commonly found in association with cardiac abnormalities: 19% prenatally and 13% at birth (Fesslova et al, 1999). The differences between the prenatal and postnatal figures are the result of the high incidence of miscarriages and stillbirths associated with cardiac abnormalities in general and the one associated with extracardiac abnormalities in particular.

4. Finding a cardiac abnormality on echocardiography (isolated or associated with other abnormalities) is an indication for detailed fetal ultrasound as well as invasive prenatal testing, such as chorionic villous sampling or amniocentesis, to determine the fetal karyotype.

B. Testing

1. In view of the high association between cardiac abnormalities and deletion at 22q11.2, FISH analysis for 22q11.2 should be considered whenever the patient decides to have an invasive prenatal test for fetal cardiac abnormality. The risk of a miscarriage associated with each of the procedures should be discussed with the patient.

2. When the cardiac abnormality is suspected or known (in an at-risk family) to be part of a single-gene disorder, the fetal DNA obtained from the genetic testing can be used for mutation analysis.

X. TAKE-HOME MESSAGE

1. Considerable progress has been made in the ability to diagnose congenital heart diseases and delineate their etiologies and prognosis.

2. Making a diagnosis of congenital heart disease in a fetus and providing the family with accurate information regarding the prognosis and the risk of recurrence can be a major challenge that requires a multidisciplinary approach involving the cardiologist, perinatologist, medical geneticists, neonatologist, and other specialties as indicated.

3. If the decision to terminate the pregnancy is undertaken or when the baby dies before or after surgery and a consent for an autopsy is given, a thorough investigation should be performed, including chromosome analysis (plus FISH) and saving fetal DNA and cells for further investigation.

4. The stored DNA and cells might provide the family with prenatal diagnosis options for future pregnancies because the gene mutations associated with different genetic conditions are being discovered rapidly.

5. Genetic counseling needs to continue to be an integral component of prenatal and postnatal diagnosis in general, but it is particularly critical in the prenatal detection of fetal abnormalities.

Allan L, Huggon IC. Counselling following a diagnosis of congenital heart disease. Prenat Diagn. 2004;24:1136-1143.

Allan LD, Sharland GK, Milburn A, et al. Prospective diagnosis of 1,006 consecutive cases of congenital heart disease in the fetus. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1994;23:1452-1458.

Berg KA, Clark EB, Astemborski JA, et al. Prenatal detection of cardiovascular malformations by echocardiography: an indication for cytogenetic evaluation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1988;159:477-481.

Brick DH, Allan LD. Outcome of prenatally diagnosed congenital heart disease: An update. Pediatr Cardiol. 2002;23(4):449-453.

Digilio MC, Marino B, Giannotti A, et al. Heterotaxy with left atrial isomerism in a patient with deletion 18p. Am J Med Genet. 2000;94(3):198-200.

Ferencz C, Neill CA, Boughman JA, et al. Congenital cardiovascular malformations associated with chromosome abnormalities: an epidemiologic study. J Pediatr. 1989;114:79-86.

Fesslova V, Nava S, Villa L. Evolution and long term outcome in cases with fetal diagnosis of congenital heart disease: Italian multicentre study. Fetal Cardiology Study Group of the Italian Society of Pediatric Cardiology. Heart. 1999;82:594-599.

Graham JMJr, Otto C. Clinical approach to prenatal detection of human structural defects. Clin Perinatol. 1990;17(3):513-546.

Harper PS. Practical Genetic Counselling, 5th ed. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann, 1998.

Nora JJ. Causes of congenital heart diseases: Old and new modes, mechanisms, and models. Am Heart J. 1993;125(5 Pt 1):1409-1419.

Nora JJ, Berg K, Nora AH. Cardiovascular Diseases: Genetics, Epidemiology and Prevention. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991.

Nora JJ, Nora AH. Familial risk of congenital heart defect. Am J Med Genet. 1988;29(1):231-233.

Nora JJ, Nora AH. Maternal transmission of congenital heart diseases: New recurrence risk figures and the questions of cytoplasmic inheritance and vulnerability to teratogens. Am J Cardiol. 1987;59(5):459-463.

Nora JJ, Nora AH. Update on counseling the family with a first-degree relative with a congenital heart defect. Am J Med Genet. 1988;29(1):137-142.

O’Connor A, O’Brian-Pallas LL. Decisional conflict. In: McFarlane GK, Macfarlane EA, editors. Nursing Diagnosis and Intervention. Toronto: Mosby; 1989:486-496.

Paladini D, Calabrò R, Palmieri S, et al. Prenatal diagnosis of congenital heart disease and fetal karyotyping. Obstet Gynecol. 1993;81:679-682.

Raymond FL, Simpson JM, Sharland GK, Ogilvie Mackie CM. Fetal echocardiography as a predictor of chromosomal abnormality. Lancet. 1997;350:930.

Touati GD, Fermont L, Neveux JY, et al. Effects of a systematic fetal detection on the outcome of severe congenital heart disease. Circulation. 1988;78:396.

Yates RW, Raymond FL, Cook A, Sharland GK. Isomerism of the atrial appendages associated with 22q11 deletion in a fetus. Heart. 1996;76(6):548-549.

E.

E.