Chapter 3 General principles of botany

morphology and systematics

‘Pick-a-cheese’ may be a widely distributed garden plant and weed known also as ‘common mallow’ which has the botanical name of Malva sylvestris or it may be some other botanical species known under the same common name.

‘Pick-a-cheese’ may be a widely distributed garden plant and weed known also as ‘common mallow’ which has the botanical name of Malva sylvestris or it may be some other botanical species known under the same common name.

Upon your request the patient brings you a branch of the plant and with the help of the scientific (botanical) literature you make a positive identification of this plant as Malva sylvestris. The identification is based on the features of the plant (leaves, fruit, flowers) that you are able to observe.

Upon your request the patient brings you a branch of the plant and with the help of the scientific (botanical) literature you make a positive identification of this plant as Malva sylvestris. The identification is based on the features of the plant (leaves, fruit, flowers) that you are able to observe.

In checking the active constituents (especially polysaccharides) you come to the conclusion that the plant is unlikely to contribute to the symptoms as they were reported by the patient. The plant is widely used as a local food item (also, for example, in Mediterranean France) and as a household remedy. Toxic natural products seem to be absent. Therefore, the search for a cause of the hypokalaemia continues…

In checking the active constituents (especially polysaccharides) you come to the conclusion that the plant is unlikely to contribute to the symptoms as they were reported by the patient. The plant is widely used as a local food item (also, for example, in Mediterranean France) and as a household remedy. Toxic natural products seem to be absent. Therefore, the search for a cause of the hypokalaemia continues…

[For further information on Norfolk country remedies readers are referred to Hatfield G 1994 Country remedies. The Boydell Press, Woodbridge.]

Plants and drugs

In the context of pharmacy a botanical drug is a product that is either:

• derived from a plant and transformed into a drug by drying certain plant parts, or sometimes the whole plant, or

• obtained from a plant, but no longer retains the structure of the plant or its organs and contains a complex mixture of biogenic compounds (e.g. fatty and essential oils, gums, resins, balms).

The large majority of botanical drugs in current use are derived from leaves or aerial parts.

Taxonomy

Example of Botanical Classification

The opium poppy, Papaver somniferum L.

Binomial: this is the genus and species names, plus the authority. Thus, in this example, Papaver somniferum is the binomial (the basic unit of taxonomy and systematics). It is followed by a short acronym (in this case ‘L.’), which indicates the botanist who provided the first scientific description of the species and who assigned the botanical name [in this example, ‘L.’ stands for Carl von Linnaeus (or Linné), a Swedish botanist (1707–1778) who developed the binomial nomenclature].*

Species: somniferum, here meaning ‘sleep-producing’.

Genus: Papaver (a group of species, in this case poppies, which are closely related).

Family: Papaveraceae (a group of genera sharing certain traits, named after one of the genera).

Subphylum: Magnoliphytina (seed-bearing plants with covered seeds).

Division (= Phylum): Spermatophyta (seed-bearing plants).

Kingdom: Plantae (the plants), one of three kingdoms, the others being the animals and fungi.

* In some cases, there is first a name in parentheses, followed by a second name not in parentheses. For example, in the case of the common aloe, Aloe vera (L.) Burm. f., the name in parentheses indicates the author (Linnaeus) who first described the species but assigned it to a different genus. The second name in this case, Burm. f., stands for the 18th century botanist Nicolaas Laurens Burman; f. stands for filius (son), since he is the son of another well-known botanist who provided numerous first descriptions of botanical species.

Morphology and anatomy of higher plants (spermatophyta)

Flower

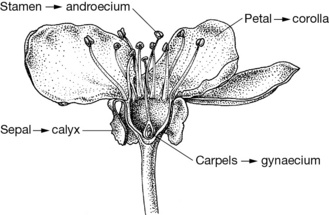

The flower (Fig. 3.1) is the essential reproductive organ of a plant. It is frequently very showy in order to attract pollinators, but in other instances the flowers are minute and difficult to distinguish from the neighbouring organs or from other flowers.

• The calyx, with individual sepals, generally serves as an outer protective cover during the budding stage of the flower. It is often greenish in colour, can be either fused or separate, and may sometimes drop off at the beginning of the flowering phase (e.g. Chelidonium majus L., greater celandine).

• The corolla, with individual petals, serves as an important element to attract the pollinator in animal-pollinated flowers. It is either fused or separate and may be very reduced, for example in plants pollinated with the help of the wind. Most commonly, the number of petals is regarded as a key feature and can vary from a well-defined number (e.g. four, five or six) to a large number that is no longer counted (written as ∞). The colour of the petals is not a good characteristic generally, since it may vary within a genus or even within a species. All of these features – i.e. the number and form of the petals, whether they are fused or not and their size – are important information for identifying a plant.

• The androecium, with its individual stamens (also known as ‘stamina’) which produce the pollen, forms a ring around the innermost part of the flower. In some species, the anther is restricted to only some of the flowers on a plant (whereas the others only have a gynaecium). In other species, androecium-bearing flowers are restricted to some plants, whereas the others bear flowers with only a gynaecium. Again, their number is important for identifying a plant.

• Gynaecium (pl. gynaecia; also called gynoecium) with individual carpels. This develops into the fruit (i.e. the seed covered by the pericarp) and includes the ovules (the part of the fruit bearing the reproductive organs which develop into the seeds).

• The stigma and style – together with the gynaecium – form the pistil. Their size and form are important differences between species.

Inflorescences

The way in which flowers are arranged to form an inflorescence is another useful feature for recognizing (medicinal) plants, but this is beyond the scope of this introduction (see Heywood 1993).

Fruit and seed

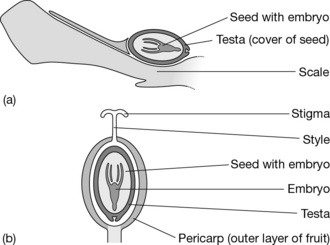

In the angiosperms, the ovule and, later, the seed are covered with a specialized organ (the carpels) which in turn develops into the pericarp (Fig. 3.2). This, the outer layer of the fruit, can either be hard as in nuts, all soft as in berries (dates, tomatoes), or hard and soft as in a drupe (cherry, olives). Drugs from the fruit thus have to be derived from an angiosperm species.

• simple (developed from a single carpel)

• aggregate (several carpels of one gynaecium are united in one fruit, as in raspberries and strawberries)

• multiple (gynaecia of more than one flower form the fruit).

Drugs

Fruits and seeds have yielded important phytotherapeutic products, including:

Leaves

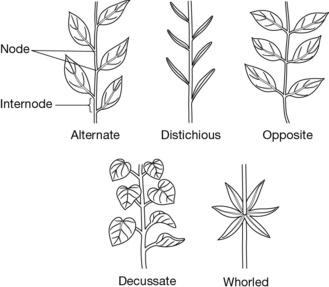

The nodes (or ‘knots’) are the parts of the stem where the leaves and lateral buds join; the intermediate area is called the internodium. A key characteristic of a species is the way in which the leaves are arranged on the stem. For example, they may be (Fig. 3.3):

• alternate: the leaves form an alternate or helical pattern around the stem, also called spiral

• distichous: there is a single leaf at each node, and the leaves of two neighbouring nodes are disposed in opposite positions

• opposite: the leaves occur in pairs, with each leaf opposing the other at the nodes

• decussate: this is a special case of opposite, where each successive pair of leaves is at a right angle to the previous pair (typical for the mint family)

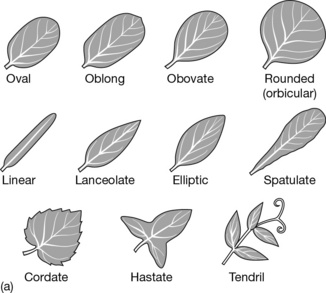

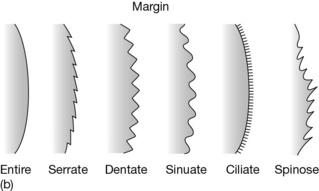

Another important characteristic is the form of the leaves. Typically, the main distinction is between simple or compound. Simple leaves have blades that are not divided into distinct morphologically separate leaflets, but form a single blade, which may be deeply lobed. In compound leaves, there are two or more leaflets, which often have their own small petioles (called petiolules). The form and size of leaves are essential characteristics (Fig. 3.4a). For example, leaves may be described as oval, oblong, rounded, linear, lanceolate, ovate, obovate, spatulate or cordate. The margin of the leaf is another characteristic feature. It can be entire (smooth), serrate (saw-toothed), dentate (toothed), sinuate (wavy) or ciliate (hairy) (Fig. 3.4b). Also, the base and the apex often have a very characteristic form.

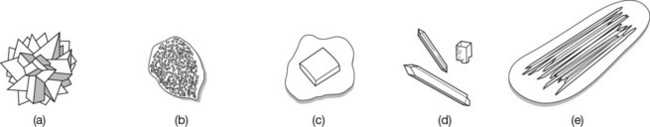

The powdered leaves of several members of the nightshade family (Solanaceae), which yield some botanical drugs that are important for the industrial extraction of the alkaloid atropine, cannot be distinguished using normal chemical methods since they all contain similar alkaloids. On the other hand, they can easily be distinguished microscopically by the presence of different forms of crystals formed by the different species and deposited in the cells (see Fig. 3.5).

Shoots (= stem, leaves and reproductive organs)

Drugs: bark

Drugs: aerial parts (= stem, leaves plus flowers/fruit)

• Ephedra, Ephedra sinica Stapf (Ephedra herba)

• Hawthorn, Crataegus monogyna Jacquin and C. laevigata (Poiret) DC. (syn. C. oxycantha) (Crataegi herba or Crataegi folium cum flore)

• Passion flower, Passiflora incarnata L. (Passiflora herba)

• Wormwood, Artemisia absinthium L. (Absinthii herba); in Africa and Asia, sweet or annual wormwood (Artemisia annua L.) is used in the treatment of malaria.

Root

Three functions of a typical root are of particular importance to a plant:

• It provides an anchor in the ground or any other substrate and thus allows the development of the plant’s above-ground organs (anchorage).

• It is the main organ for the uptake of water and inorganic nutrients (absorption and conduction).

• It often serves to store surplus energy, generally in the form of polysaccharides such as starch and inulin (storage).

Rootstock and specialized underground organs

Rhizome and root (radix) drugs

• Devil’s claw, Harpagohytum procumbens DC. ex Meissner (Harpagophyti radix, thickened roots)

• Korean ginseng, Panax ginseng C. A. Meyer (Ginseng radix)

• Tormentill, Potentilla erecta (L.) Raeuschel (syn. P. tormentilla, Potentillae radix)

• Echinacea, Echinacea angustifolia DC., E. pallida Nuttall and E. purpurea (L.) Moench (Echinacea radix)

• Siberian ginseng, Eleutherococcus senticosus Maximimowicz (Eleutherococci radix)

• Kava-kava, Piper methysticum Forster f. (kava-kava rhizoma)

• Chinese foxglove root, Rehmannia glutinosa Libosch (Rehmannia radix)

• Rhubarb, Rheum palmatum L. and Rh. officinale Baillon, as well as their hybrids (Rhei radix, thickened roots)

• Sarsaparilla, Smilax regelii Killip & Morton and Smilax spp. (Sarsaparillae radix).