GENERAL PRINCIPLES AND CONCEPTS OF SELECTED MOVEMENTS AND SPECIAL TESTS

Principles of Movement Examination

• Before beginning the physical examination, the examiner should have a working hypothesis on which to base the assessment. If you cannot make a preliminary diagnosis from the history, supplemented by observation, before you begin the examination, either you have not asked enough questions or you have not asked the right questions.

• Communication and rapport are essential to gaining a patient’s trust. The patient has the right to be informed about all aspects of the examination process. Be sure to tell the patient what you are doing and to explain clearly what you want the patient to do and why it is necessary.

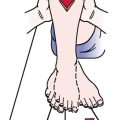

• Unless bilateral movement is required, you should test the normal (uninvolved) side first. Testing the normal side first allows the examiner to establish a baseline for normal movement of the joint being tested. It also demonstrates to the patient what to expect, which increases the patient’s confidence and eases the patient’s apprehension when the injured side is tested.

• In comparing the normal and injured limbs, you must use the same testing methods for both limbs. This means using the same initial starting position and applying the same amount of gentle force at the same point or throughout the range. You should note the position at which any changes occur.

• The patient performs active movements before you perform passive movements. Passive movements are followed by resisted isometric movements. This approach gives the examiner a better idea of what the patient thinks he or she can do before the structures are fully tested.

• You should perform any movements that are painful last, if possible, to prevent an overflow of painful symptoms to the next movement, which actually may be symptom free.

• During active movements, if the range of motion (ROM) is full, you may apply overpressure carefully to determine the end feel of the joint. This often negates the need to do passive movements.

• If active ROM is not full, you may apply overpressure but only with extreme care to prevent an exacerbation of symptoms.

• You may repeat each active, passive, or resisted isometric movement several times or hold (sustain) the contraction for a certain amount of time to see whether:

A different pattern of movement results

A different pattern of movement results

Weakness increases or indications of possible vascular insufficiency are noted

Weakness increases or indications of possible vascular insufficiency are noted

• This repetitive or sustained activity is especially important if the patient has complained that repetitive movement or sustained postures alter symptoms.

• You should do resisted isometric movements with the joint in a neutral or resting position so that stress on the inert tissues is minimal. Any symptoms produced by the movement then are more likely to be caused by problems with contractile tissue.

• For passive ROM or ligament testing, it is important that you determine not only the degree (i.e., amount) of movement, but also the quality (i.e., end feel) of the movement.

• When you are testing the ligaments, apply the appropriate stress gently and repeat this several times. The stress is increased up to but not beyond the point of pain, thereby demonstrating maximum instability without causing muscle spasm.

• When testing myotomes (i.e., groups of muscles supplied by a single nerve root), you should hold each contraction for a minimum of 5 seconds to see whether weakness becomes evident. Myotomal weakness takes time to develop, because the muscles are supplied by more than one nerve root.

• A thorough examination often involves stressing and aggravating different tissues. At the completion of an assessment, you must warn the patient that symptoms may be exacerbated as a result of the assessment. This prevents the patient from thinking that any initial treatment may have made the condition worse, which in turn might make the patient hesitant to return for further treatment.

• Clinical decision making is a continuous process of communication, hypothesis generation, assessment, and hypothesis revision. During the examination, you will look for subjective signs and symptoms (i.e., what the patient feels) and objective signs and symptoms (i.e., what you deduce from the various tests the patient performs) and then use this information to shape your hypothesis and subsequent decisions.

• A quick scanning examination is not meant to rule in or out a particular pathologic condition. Rather, it is performed to determine whether a more thorough examination of a region is needed. A scanning examination is used in the following circumstances:

To rule out signs and symptoms referred distally from the spine, spinal cord, or nerve roots to other parts of the body (e.g., sciatica)

To rule out signs and symptoms referred distally from the spine, spinal cord, or nerve roots to other parts of the body (e.g., sciatica)

To help rule out problems in the spine that may be causing signs and symptoms elsewhere

To help rule out problems in the spine that may be causing signs and symptoms elsewhere

To determine the level of the spine that is affected

To determine the level of the spine that is affected

When signs and symptoms are felt in a peripheral joint or one of the limbs but the patient has no history of injury in that area

When signs and symptoms are felt in a peripheral joint or one of the limbs but the patient has no history of injury in that area

When radicular signs are present

When radicular signs are present

When the patient has no history of injury or overuse

When the patient has no history of injury or overuse

When trauma with radicular signs is present

When trauma with radicular signs is present

When altered sensation in a limb is present

When altered sensation in a limb is present

When spinal cord (“long track”) signs are present

When spinal cord (“long track”) signs are present

• When testing movement, you must determine whether pain or restriction is the predominant problem.

Active Movements

• When and where pain occurs during each movement

• Whether movement changes the intensity and quality of the pain

• The patient’s reaction to pain

Does there appear to be neural control?

Does there appear to be neural control?

Are the proper muscles recruited and in the proper sequence?

Are the proper muscles recruited and in the proper sequence?

Does the movement occur at the correct speed?

Does the movement occur at the correct speed?

• The rhythm and quality of movement

• The amount of observable restriction (i.e., freedom of movement)

Resisted Isometric Movements

• Whether the contraction is painful

• The strength of the contraction

• The type of contraction that causes symptoms (e.g., concentric, eccentric)

• The patient’s ability to control movement (i.e., the ability to do the movement correctly)

• The way the muscle is functioning (e.g., as an agonist or a synergist)

• Whether the muscle is weak and long (phasic) or tight and strong (weak and long muscles are often considered phasic and strong; and shortened muscles are considered postural/tonic)

Special Diagnostic Tests

Special diagnostic tests are designed to confirm a diagnosis. As such, they may:

• Test specific structures (e.g., stability tests)

• Differentiate between tissues (e.g., for thoracic outlet syndrome)

• Provoke symptoms (e.g., provocative or neurodynamic tests)

Points to remember about special diagnostic tests include the following:

• They depend on (1) the examiner’s ability to perform the test, (2) the examiner’s skill in doing the test; and (3) the patient’s ability to relax.

• They should never be used alone or in isolation. As an examiner, you will use these tests in conjunction with other testing to confirm a diagnosis.

• They are most accurate (1) immediately after an injury (because of tissue shock); (2) when the patient is under anesthesia; and (3) in chronic conditions.

Special tests should be used with caution in the presence of: