2 General patient examination and differential diagnosis

General examination of a patient

Physique and nutrition

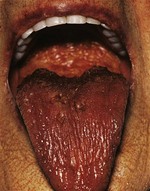

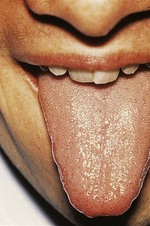

The nutritional state of a patient may provide an important indicator of disease, and prompt correction of a deficient nutritional state may improve recovery. The more detailed methodologies available for nutritional assessment and management in the context of complex gastrointestinal disease are covered in Chapter 12. In the general survey, note if the patient is cachectic, slim, plump or obese. If obese, is it generalised or centrally distributed? Wasting of the temporalis muscle leads to a gaunt appearance and recent weight loss may result in prominence of the ribs. Other clues to poor nutrition include cracked skin, loss of scalp and body hair and poor wound healing. Malnutrition accompanying illness results in blood albumin being low leading to oedema, making overall body weight an unreliable marker of malnutrition. A smooth, often sore tongue without papillae (atrophic glossitis, Fig. 2.1) suggests important vitamin B deficiencies. Angular stomatitis (cheilosis, a softening of the skin at the angles of the mouth followed by cracking) may occur with a severe deficiency of iron or B vitamins (Fig. 2.1). Niacin deficiency, if profound, may cause the typical skin changes of pellagra (Fig. 2.2).

Hands

Examine the hands carefully as diagnostic information from a variety of pathologies may be evident. The strength of the patient’s grip may be informative with regard to underlying neurological or musculoskeletal disorders. Characteristic patterns of muscular wasting may accompany various neuropathies and radiculopathies (see Ch. 14). Make note of any tremor, taking care to distinguish the fine tremor of thyrotoxicosis or recent beta-adrenergic therapy, from the rhythmical ‘pill rolling’ tremor of parkinsonism (see Ch. 14), and from the coarse jerky tremor of hepatic or uraemic failure (sufficiently slow to be referred to as a metabolic ‘flap’).

Feel for Dupuytren’s contracture in both hands, the first sign of which is usually a thickening of tissue over the flexor tendon of the ring finger at the level of the distal palmar crease. With time, puckering of the skin in this area develops, together with a thick fibrous cord, leading to flexion contracture of the metacarpophalangeal and proximal interphalangeal joints. Flexion contracture of the other fingers may follow (Fig. 2.3).

Figure 2.3 Dupuytren’s contracture.

(From Forbes and Jackson 2002 Color Atlas and Text of Clinical Medicine, 3rd edn, Mosby, Edinburgh. Reproduced by kind permission.)

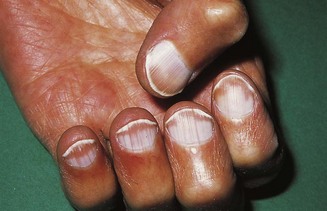

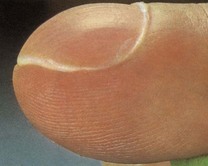

In clubbing of the fingers, the tissues at the base of the nail are thickened and the angle between the base of the nail and the adjacent skin of the finger is lost. The nail becomes convex both transversely and longitudinally and, in gross cases (usually due to severe cyanotic heart disease, bronchiectasis or empyema), the volume of the finger pulp increases (Fig. 2.4). Lesser degrees of clubbing may be seen in bronchial carcinoma, fibrosing alveolitis, inflammatory bowel disease and infective endocarditis. The last of these may also be associated with Osler’s nodes – transient, tender swellings due to dermal infarcts from septic cardiac vegetations (Fig. 2.5). Splinter haemorrhages (Fig. 2.6) and nail-fold infarctions (Fig. 2.7) may be signs of a vasculitic process, but may also be the result of trauma in normal individuals and are therefore rather non-specific.

Figure 2.4 Clubbing of the fingers. This case is very marked.

(From Forbes and Jackson 2002 Color Atlas and Text of Clinical Medicine, 3rd edn, Mosby, Edinburgh. Reproduced by kind permission.)

Figure 2.5 Small dermal infarcts in infective endocarditis.

(From Forbes and Jackson 2002 Color Atlas and Text of Clinical Medicine, 3rd edn, Mosby, Edinburgh. Reproduced by kind permission.)

Figure 2.6 Splinter haemorrhages.

(From Forbes and Jackson 2002 Color Atlas and Text of Clinical Medicine, 3rd edn, Mosby, Edinburgh. Reproduced by kind permission.)

Figure 2.7 Nail-fold infarction.

(From Forbes and Jackson 2002 Color Atlas and Text of Clinical Medicine, 3rd edn, Mosby, Edinburgh. Reproduced by kind permission.)

Trophic changes may be evident in the skin in certain neurological diseases and in peripheral circulatory disorders such as Raynaud’s syndrome, in which vasospasm of the digital arterioles causes the fingers to become white and numb, followed by blue/purple cyanosis and then redness due to arteriolar dilatation and reactive hyperaemia (Fig. 2.8).

Figure 2.8 Raynaud’s syndrome in the acute phase with severe blanching of the tip of one finger.

(From Forbes and Jackson 2002 Color Atlas and Text of Clinical Medicine, 3rd edn, Mosby, Edinburgh. Reproduced by kind permission.)

In koilonychia the nails are soft, thin, brittle and the normal convexity replaced by a spoon-shaped concavity (Fig. 2.9). It is usually due to longstanding iron-deficient anaemia. Leuconychia (opaque white nails) may occur in chronic liver disease and other conditions associated with hypoalbuminaemia (Fig. 2.10).

Lymph glands and lymphadenopathy

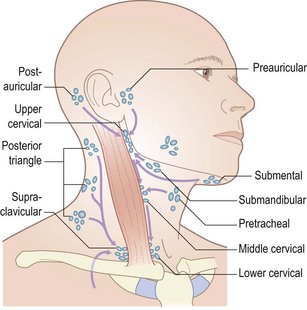

Details pertaining to the examination of specific lymph node groups may be found in the relevant chapters (e.g. Ch. 20 for cervical lymphadenopathy). Here, the principles of palpating for lymphadenopathy will be covered. Lymph nodes are interposed along the course of lymphatic channels and their enlargement should always be noted. Lymph from the arm drains into the axillary nodes. These should be routinely examined, but particularly in conjunction with examination of the breast (see below). Lymph from the lower limbs drains via deep and superficial inguinal nodes, although only the latter can be palpated and, in turn, comprise a vertical and horizontal group. The vertical inguinal nodes lie close to the upper part of the long saphenous vein and drain the leg. The horizontal group lies above the inguinal ligament and drains the lower abdominal skin, anal canal, external genitalia (excluding the testes), buttocks and lower vagina.

Examination of lymph nodes involves inspection and palpation. Inflammation of the overlying skin and associated pain usually implies an infective aetiology, whereas malignant lymphadenopathy is usually non-tender. To palpate for lymphadenopathy, use the pulps of your fingers (usually the index and middle but, for large nodes, the ring as well) to move the skin overlying the potentially enlarged node(s). Determine the size, position, shape, consistency, mobility, tenderness and whether it is an isolated lymph node or whether several coalesce. For the head and neck nodes, it is often helpful to tilt the head slightly towards the side of examination in order to relax the overlying muscles. Feel for each of the groups shown in Figure 2.11 in whatever order you find most efficient and reliable. Muscles and arteries in the neck and groin may be mistaken for lymph nodes. If in doubt, try to move the structure in question in two directions (laterally and superior to inferior). It should be possible to move a lymph node in two directions, but not an artery or muscle.

Determining whether a lymph node is pathological can be difficult and requires practice and experience. In general, small, mobile, discrete lymph nodes are frequently found in normal individuals, particularly those who are slim and have little overlying adipose tissue. The finding of an enlarged lymph node should prompt the question ‘Is this consequent upon local pathology, for example infection or malignancy, or is it part of a more generalized abnormality of the reticuloendothelial system (including other lymph node groups, liver and spleen)?’ (Fig. 2.12).

Axillae

Most information from examination of the axillae comes from palpation for possible lymphadenopathy (Fig. 2.13), but inspection may reveal an absence/paucity of secondary sexual hair in either gender (most commonly in association with chronic liver disease, but also in certain endocrinopathies), abnormal skin colouring, such as the dark velvety appearance of acanthosis nigricans, or (very rarely and almost always in the presence of café au lait spots elsewhere) the characteristic freckling of von Recklinghausen’s disease.

Skin

Examination of the skin with respect to specific dermatological diagnoses is covered in Chapter 15. In the context of the general examination, the most important features relate to temperature, hydration, pallor, colour/pigmentation and cyanosis. Use the back of your fingers to assess the temperature of the skin. This complements rather than replaces the formal measurement with a thermometer. There may be generalized warmth in febrile illness or thyrotoxicosis, or localized warmth if there is regional inflammation. Cold skin may be localized, such as when a limb is deprived of its blood supply, or generalized in states of circulatory failure, when the skin feels clammy and sweaty.

Lift a fold of skin and make note of its thickness, mobility and how easily it returns to its original position (turgor). The skin on the back of the hand is often thin and fragile in elderly patients, may show decreased mobility in scleroderma (Fig. 2.14) or in oedematous states, and have reduced turgor in the presence of dehydration. The skin of acromegalic patients is typically thick and greasy.

Figure 2.14 Advanced scleroderma.

(From Forbes and Jackson 2002 Color Atlas and Text of Clinical Medicine, 3rd edn, Mosby, Edinburgh. Reproduced by kind permission.)

An important determinant of skin colour is the relative amount of oxyhaemoglobin and deoxyhaemoglobin. Oxyhaemoglobin is a bright red pigment. An increase in its flow beneath thinned facial skin causes the characteristic plethora of Cushing’s syndrome (Fig. 2.15), whereas a decrease in flow causes pallor. As blood passes through the capillary bed, oxygen is given up to metabolizing tissues to produce deoxyhaemoglobin. This has a darker, less red, more bluish pigment and its presence in peripheral blood vessels in increased amounts causes the clinical sign of cyanosis. There are two physiological types of cyanosis: peripheral and central. Peripheral cyanosis is associated with increased extraction of oxygen from capillaries when peripheral blood flow is slowed, often due to vasospasm caused by cold, heart failure or anxiety. The cyanosed extremity is usually cold and the tongue is unaffected. Any condition causing slowing of the peripheral circulation may lead to peripheral cyanosis as there is more time for oxygen extraction. Central cyanosis is caused by inadequate oxygenation of blood, in turn due to heart failure, serious respiratory disease or mixing of venous and arterial blood across a right to left cardiac shunt. In the latter situation, blood passes directly from the right to the left side of the heart, without passing through the pulmonary circulation, thereby failing to become oxygenated. Central cyanosis is generalized and the peripheries are often warm. At least 5 g/dl of reduced haemoglobin is necessary to produce central cyanosis, and it is therefore less marked in anaemic patients. The cyanosis of heart failure is often due to both peripheral and central causes. The presence of central cyanosis is best appreciated at the lips, mucous membranes and conjunctivae, where the keratinized skin is thinnest (Fig. 2.16).

Pulses

Arterial pulses are detected by compressing the relevant vessel against a firm underlying structure, usually a bone. Details of the characteristic pulse abnormalities that help in the diagnosis of various cardiac disorders are described in Chapter 11, but palpation of all the peripheral pulses should form part of the general examination of all patients. Some may be difficult to feel and you may need to vary the degree of pressure in order to pick up the relevant pulsation. On occasion, you may confuse the patient’s pulse with your own. Count your own heart rate and compare it with the patient’s as they will usually be different.

Legs and feet

Examination of the legs requires adequate exposure from the groins and buttocks to the toes. Note the colour and texture of the skin. Peripheral vascular disease often makes the skin shiny and hair does not grow on ischaemic legs or feet (Fig. 2.17). Pressure on the toes of ischaemic feet will cause blanching of the characteristic purple colour with subsequent slow return. Passive elevation of an ischaemic leg leads to marked pallor of the foot as perfusion against gravity falls. Painless trophic lesions, often with deep ulceration, may be seen in diabetic peripheral neuropathy. The posterior aspect of the heels is a particularly important area to inspect in elderly, emaciated or neurologically impaired patients, all of whom are vulnerable to pressure sores caused by obliteration of arteriolar and capillary blood flow to the skin.

Figure 2.17 Peripheral vascular disease. There is pallor, loss of hair and early ulceration on the dorsum of three toes.

(From Forbes and Jackson 2002 Color Atlas and Text of Clinical Medicine, 3rd edn, Mosby, Edinburgh. Reproduced by kind permission.)

Inspect the legs for obvious oedema and examine for pitting oedema. Press firmly but gently for around 5 seconds behind the medial malleolus, over the dorsum of the foot and on the shin. If oedema is present, a depression/concavity will form (Fig. 2.18).

Varicose veins should be examined for with the patient standing (Fig. 2.19). Superficial varicosities are generally obvious in this position, whereas the efficiency of the valves of the long saphenous vein should be assessed by Trendelenburg’s test. With the patient lying, the saphenous vein is emptied by elevating the leg. Occlude the upper end of the vein by finger pressure on the saphenous vein opening (alternatively use a tourniquet) and ask the patient to stand while maintaining this pressure. If the valves are incompetent, the veins will rapidly fill from above when the pressure is released.

Putting it all together

General

Overall appearance (well, unwell, severely ill; neglected or well-cared for).

Overall appearance (well, unwell, severely ill; neglected or well-cared for).

Skin colour, cyanosis, jaundice, anaemia.

Skin colour, cyanosis, jaundice, anaemia.

Skin lesions (spider naevi, vitiligo, purpura, petechiae).

Skin lesions (spider naevi, vitiligo, purpura, petechiae).

Body hair (distribution, quantity).

Body hair (distribution, quantity).

Vital signs (temperature, pulse, respiration rate).

Vital signs (temperature, pulse, respiration rate).

Obvious features of endocrine disease (e.g. Cushing’s, acromegaly, hyperlipidaemia).

Obvious features of endocrine disease (e.g. Cushing’s, acromegaly, hyperlipidaemia).

Cardiovascular and respiratory (anterior, patient semi-recumbent)

Abdomen

Inspection: size, distension, asymmetry, scars, abdominal wall movements, dilated vessels, visible peristalsis, pulsations, pubic hair, spider naevi.

Inspection: size, distension, asymmetry, scars, abdominal wall movements, dilated vessels, visible peristalsis, pulsations, pubic hair, spider naevi.

Palpation: tenderness, rigidity, hyperaesthesia, masses, organomegaly, hernial orifices, inguinal lymphadenopathy, genitalia, digital rectal (where relevant).

Palpation: tenderness, rigidity, hyperaesthesia, masses, organomegaly, hernial orifices, inguinal lymphadenopathy, genitalia, digital rectal (where relevant).

Documentation and communication

Mr JW, aged 32, manual labourer, married, 2 children.

Generally in excellent health and symptom free. Keen sportsman.

No relevant past medical history.

Sudden-onset right-sided chest pain.

Sudden-onset right-sided chest pain.

Associated severe breathlessness; unable to get comfortable.

Associated severe breathlessness; unable to get comfortable.

No cough or sputum or haemoptysis.

No cough or sputum or haemoptysis.

Mr JW, aged 32, manual labourer, married, 2 children.

Generally in excellent health and symptom free. Keen sportsman.

Sudden-onset right-sided chest pain.

Sudden-onset right-sided chest pain.

Associated severe breathlessness; unable to get comfortable.

Associated severe breathlessness; unable to get comfortable.

No cough or sputum or haemoptysis.

No cough or sputum or haemoptysis.

Many patients have had medical and surgical episodes in their history that are essentially ‘closed events’, for example cataract removal, hernia repair or tonsillectomy as a child. Although they may seem irrelevant to the current problem, they may, subsequently, provide important useful information and it is important to document them meticulously. For example, knowing that a bilateral oophorectomy was performed at the time of a hysterectomy is helpful information in the assessment of a woman with ascites. The past medical history (if accurate) makes a diagnosis of carcinoma of the ovary highly improbable. Documentation of any surgical procedures, however minor, can provide reassuring or helpful anticipatory information in patients likely to undergo general anaesthesia. Recording of the history concludes with the full list of drugs, doses and dosing intervals, any adverse reactions to previously prescribed medicines and documentation of the review of systems (see Ch. 1).

Details of the physical examination should be documented in a clear, structured framework. Start with a general, non-judgemental comment about the patient’s overall appearance, such as ‘well man with moderate generalized adiposity’ or ‘drawn, anxious woman, breathless on undressing’. Record important positive and negative features on general examination, for example jaundice, clubbing, rash, fever, lymphadenopathy. The remainder of the examination should be documented under bodily systems: cardiovascular, respiratory, gastrointestinal (often referred to as abdominal), nervous system, skin, limbs and joints. Negative findings are often as pertinent as positive ones. Simple line drawings are often particularly effective. A concise summary of the findings in the cardiovascular system might read as in Box 2.1.

Constructing a differential diagnosis

In patients who are severely ill, the measured approach in which subjective and objective clinical information is moulded into a comprehensive differential diagnosis has to give way to a more direct, ‘functional’ approach in which the imperative is emergency correction of abnormal physiological parameters, for example hypotension, hypoxia or safeguarding an airway/cervical spine. This more urgent, focused style of clinical method is described in Chapter 8.

Some helpful principles to follow include the following:

Make a list of the patient’s major symptoms and the signs you have elicited on examination.

Make a list of the patient’s major symptoms and the signs you have elicited on examination.

Where possible, try to localize the clinical and anatomical findings. In some cases, this may be straightforward (e.g. a painful, swollen, hot, red knee) but in others this may be more diffuse (e.g. abdominal pain without abnormal examination findings) or not possible at all (e.g. weight loss and fatigue).

Where possible, try to localize the clinical and anatomical findings. In some cases, this may be straightforward (e.g. a painful, swollen, hot, red knee) but in others this may be more diffuse (e.g. abdominal pain without abnormal examination findings) or not possible at all (e.g. weight loss and fatigue).

Start with the most specific findings to formulate your clinical hypothesis. If a patient reports fatigue, abdominal pain, weight loss and you find an abdominal mass on examination, then focus your differential diagnosis around the mass rather than the fatigue which is a less specific feature.

Start with the most specific findings to formulate your clinical hypothesis. If a patient reports fatigue, abdominal pain, weight loss and you find an abdominal mass on examination, then focus your differential diagnosis around the mass rather than the fatigue which is a less specific feature.

Think about possible pathological and/or physiological causes that might explain your patient’s symptoms. This will become easier as you read more about disease processes, but a helpful, frequently used ‘thinking framework’ is given in Box 2.2. Using this, try to correlate the combination of subjective and objective data with your list of possibilities. Certain features will help eliminate certain causes, e.g. the age of the patient and the time course of the illness, but at the start of your learning it is helpful to rehearse in your mind a wide range of possible causes.

Think about possible pathological and/or physiological causes that might explain your patient’s symptoms. This will become easier as you read more about disease processes, but a helpful, frequently used ‘thinking framework’ is given in Box 2.2. Using this, try to correlate the combination of subjective and objective data with your list of possibilities. Certain features will help eliminate certain causes, e.g. the age of the patient and the time course of the illness, but at the start of your learning it is helpful to rehearse in your mind a wide range of possible causes.

Try, at least initially, to account for the patient’s symptoms and findings by one disease process (the principle of Occam’s razor: entia non sunt multiplicanda praeter necessitatem; one should not increase, beyond what is necessary, the number of entities required to explain anything).

Try, at least initially, to account for the patient’s symptoms and findings by one disease process (the principle of Occam’s razor: entia non sunt multiplicanda praeter necessitatem; one should not increase, beyond what is necessary, the number of entities required to explain anything).

Always try to explain the totality of the patient’s complaints. For example, the diagnosis of typical dyspeptic symptoms associated with use of over-the-counter non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may be straightforward, but why was it necessary to take the NSAIDs in the first place? In such a situation, a more complete diagnostic possibility would be ‘probable osteoarthritis, leading to excessive use of NSAIDs with consequent non-ulcer dyspepsia/peptic ulceration’.

Always try to explain the totality of the patient’s complaints. For example, the diagnosis of typical dyspeptic symptoms associated with use of over-the-counter non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may be straightforward, but why was it necessary to take the NSAIDs in the first place? In such a situation, a more complete diagnostic possibility would be ‘probable osteoarthritis, leading to excessive use of NSAIDs with consequent non-ulcer dyspepsia/peptic ulceration’.

Always go through the mental discipline of challenging ‘established’ diagnoses before you ascribe the current problem to an evolution/complication of a previous one. For example, if a patient with a sternotomy and saphenous vein harvesting scars from previous coronary artery bypass grafting reports a familiar chest discomfort on exercise last experienced prior to surgery, such a scenario is eminently ‘logical’ and likely to need little further diagnostic enquiry. However, if a young patient, without obvious risk factors for ischaemic heart disease, reports that he has chest pain similar to several other ‘heart attacks’ but has a completely normal clinical examination and electrocardiogram, it may be that he has had a series of limited myocardial infarctions, but another possibility is that he has misunderstood or misremembered the outcome of previous episodes and that alternative explanations should be explored.

Always go through the mental discipline of challenging ‘established’ diagnoses before you ascribe the current problem to an evolution/complication of a previous one. For example, if a patient with a sternotomy and saphenous vein harvesting scars from previous coronary artery bypass grafting reports a familiar chest discomfort on exercise last experienced prior to surgery, such a scenario is eminently ‘logical’ and likely to need little further diagnostic enquiry. However, if a young patient, without obvious risk factors for ischaemic heart disease, reports that he has chest pain similar to several other ‘heart attacks’ but has a completely normal clinical examination and electrocardiogram, it may be that he has had a series of limited myocardial infarctions, but another possibility is that he has misunderstood or misremembered the outcome of previous episodes and that alternative explanations should be explored.

Always consider the possibility that some, if not all, of the patient’s symptoms may relate to the side effects of prescribed or non-prescribed medications (particularly in the elderly).

Always consider the possibility that some, if not all, of the patient’s symptoms may relate to the side effects of prescribed or non-prescribed medications (particularly in the elderly).

Always include in your list of possibilities potentially serious and treatable conditions, because the consequences of a delayed or missed diagnosis are severe for the patient, and sometimes for the doctor also (e.g. subarachnoid haemorrhage in a patient with acute severe headache).

Always include in your list of possibilities potentially serious and treatable conditions, because the consequences of a delayed or missed diagnosis are severe for the patient, and sometimes for the doctor also (e.g. subarachnoid haemorrhage in a patient with acute severe headache).

The beginnings of a management plan

The word ‘management’ in this context refers to a clinical strategy that is a combination of monitoring, selection of further informative diagnostic tests and treatment. It may therefore be thought of as the clinical process whereby the patient is taken from the point of initial assessment through to final diagnosis and appropriate treatment, the outcome of which may vary from full recovery to death. In general practice or the outpatient clinic, the emphasis, initially, is likely to be on selecting informative investigations, although these may be accompanied at the same time by simple recommendations for treatment that will be applicable whatever the final diagnosis, such as lifestyle changes (weight loss, smoking cessation) or blood pressure control. In acutely ill patients, monitoring and emergency treatment are likely to feature more than investigations, at least until the situation is more stable. A good example of this is acute pulmonary oedema, in which measures to relieve breathlessness and monitoring for cardiac arrhythmias (sitting the patient up, provision of high-flow oxygen, intravenous opiates, connection to an ECG monitor) are needed urgently. Diagnostically informative echocardiography can usually follow in the subsequent hours or days. In general, Box 2.3 suggests an order of tasks to follow when constructing your provisional management plan. In some patients (particularly the elderly), it may also be appropriate to detail any additions/improvements to the social support network that exists, in preparation for the patient’s discharge.

Box 2.3 Order of tasks to follow when constructing a provisional management plan

1 List the monitoring/nursing recommendations that are imperative to the patient’s immediate comfort, wellbeing and safety

2 List the investigations that need to be done immediately (e.g. blood cultures and malaria film in a patient returning from overseas with a fever of unknown origin)

3 Document the medications you propose to prescribe, including the doses and frequency of administration (this includes intravenous fluid therapy)

4 List the investigations that may need to be done at some stage in order to provide further diagnostic information

Selecting appropriate investigations

Ask yourself the following questions when considering which investigations to request:

Will this test confirm/complement the information derived from the history and examination?

Will this test confirm/complement the information derived from the history and examination?

Will this test provide new information (such as a chest X-ray in a patient with a productive cough and weight loss but no physical findings on examination)?

Will this test provide new information (such as a chest X-ray in a patient with a productive cough and weight loss but no physical findings on examination)?

Could this test provide useful information over a period of time as a marker of disease progression (e.g. the inflammatory markers erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) in a patient with infective endocarditis. Neither test is specific for the diagnosis but changes in both values may be useful markers of disease progression)?

Could this test provide useful information over a period of time as a marker of disease progression (e.g. the inflammatory markers erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) in a patient with infective endocarditis. Neither test is specific for the diagnosis but changes in both values may be useful markers of disease progression)?

What are the possibilities of this test yielding clinically irrelevant/distracting information compared to a diagnostically informative result? A good example of this would be the indiscriminate use of cranial computed tomography (CT) scans in patients with ill-defined neurological symptoms (such as dizziness) before a detailed neurological examination has been performed. Meningiomas (benign tumours arising from the meninges) are not-infrequent findings in patients undergoing cranial imaging. In a patient with dizziness without other neurological symptoms or signs, such a finding is likely to be irrelevant and, because the meningioma will need routine surveillance, is likely to cause unnecessary anxiety. In contrast, the finding of a meningioma in a patient with a carefully taken history of focal seizures is likely to be highly relevant (and, in fact, a reassuring finding for many patients as the differential diagnosis includes many other, more aggressive, brain tumours with a bleak outlook).

What are the possibilities of this test yielding clinically irrelevant/distracting information compared to a diagnostically informative result? A good example of this would be the indiscriminate use of cranial computed tomography (CT) scans in patients with ill-defined neurological symptoms (such as dizziness) before a detailed neurological examination has been performed. Meningiomas (benign tumours arising from the meninges) are not-infrequent findings in patients undergoing cranial imaging. In a patient with dizziness without other neurological symptoms or signs, such a finding is likely to be irrelevant and, because the meningioma will need routine surveillance, is likely to cause unnecessary anxiety. In contrast, the finding of a meningioma in a patient with a carefully taken history of focal seizures is likely to be highly relevant (and, in fact, a reassuring finding for many patients as the differential diagnosis includes many other, more aggressive, brain tumours with a bleak outlook).

What are the potential risks and discomfort to the patient of the proposed test (including the risk of unnecessary anxiety generated by an irrelevant finding demanding further evaluation)? In the case of routine haematological and biochemical tests requiring straightforward venepuncture, the immediate risk (aside from minor discomfort) is low. In the case of coronary angiography, the risk of death is around 0.1% and of serious complication (myocardial infarction, stroke, arrhythmia, cardiac perforation) approximately 1.7%. Following a kidney biopsy, the risk of a haemorrhage sufficiently severe to require an emergency nephrectomy is around 0.0003% (1 in 3000). In these, and other, situations, the clinician must balance benefit and risk. The benefit can be diagnostic information leading to targeted treatment of a serious illness, or excluding problems for which the treatment has significant risk. The risk is that of the investigation itself, or of the anxiety or distress that it may provoke.

What are the potential risks and discomfort to the patient of the proposed test (including the risk of unnecessary anxiety generated by an irrelevant finding demanding further evaluation)? In the case of routine haematological and biochemical tests requiring straightforward venepuncture, the immediate risk (aside from minor discomfort) is low. In the case of coronary angiography, the risk of death is around 0.1% and of serious complication (myocardial infarction, stroke, arrhythmia, cardiac perforation) approximately 1.7%. Following a kidney biopsy, the risk of a haemorrhage sufficiently severe to require an emergency nephrectomy is around 0.0003% (1 in 3000). In these, and other, situations, the clinician must balance benefit and risk. The benefit can be diagnostic information leading to targeted treatment of a serious illness, or excluding problems for which the treatment has significant risk. The risk is that of the investigation itself, or of the anxiety or distress that it may provoke.

What information does the laboratory and/or radiology department require to make this test maximally useful? A biopsy or surgical specimen sent to the pathology laboratory is likely to yield much more diagnostic information when accompanied by clinical details and a specific question than if delivered, speculatively, without either.

What information does the laboratory and/or radiology department require to make this test maximally useful? A biopsy or surgical specimen sent to the pathology laboratory is likely to yield much more diagnostic information when accompanied by clinical details and a specific question than if delivered, speculatively, without either.

If the diagnosis is not apparent after some effort at investigation, at some point clinicians should stop to ask themselves the questions listed in Box 2.4.

If the diagnosis is not apparent after some effort at investigation, at some point clinicians should stop to ask themselves the questions listed in Box 2.4.

Box 2.4 What to think about if the diagnosis is not apparent after some degree of investigation

1 Has a serious problem been sufficiently excluded and could empirical treatment be tried, or is the patient reassured enough to ‘live with his symptoms’?

2 Could a common diagnosis have been missed, and therefore one or more tests should be repeated?

3 Is there a need for an ongoing search for rarer diagnoses with more detailed investigation?