Chapter 628 General Considerations and Evaluation

Physical Examination

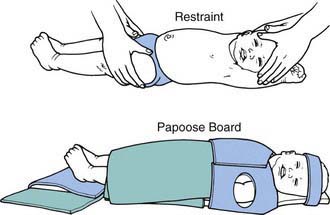

The position of the patient for examination of the ear, nose, and throat depends on the patient’s age and ability to cooperate, the clinical setting, and the examiner’s preference. The child can be examined on an examination table or in the parent’s lap. The presence of a parent or assistant usually is necessary to minimize movement and provide better examination results (Fig. 628-1). An examining table may be desirable for uncooperative older infants or when a procedure, such as microscopic evaluation or tympanocentesis, is performed. Wrapping the child in a sheet or using a papoose board can help to minimize movement. Lap examination is adequate and preferable in most infants and young children; the parent may assist in restraining the child by folding the child’s wrists and arms over the child’s own abdomen with one hand and holding the child’s head against the parent’s chest with the other hand. If necessary, the child’s legs can be held between the parent’s knees. To avoid ear trauma with movement, the examiner should hold the otoscope with the hand placed firmly against the child’s head or face, so that the otoscope moves with the head. Pulling up and out on the pinna straightens the ear canal and allows better exposure of the TM.

Figure 628-1 Methods of restraining an infant for examination and for procedures such as tympanocentesis or myringotomy.

(From Bluestone CD, Klein JO: Otitis media in infants and children, ed 2, Philadelphia, 1995, WB Saunders, p 91.)

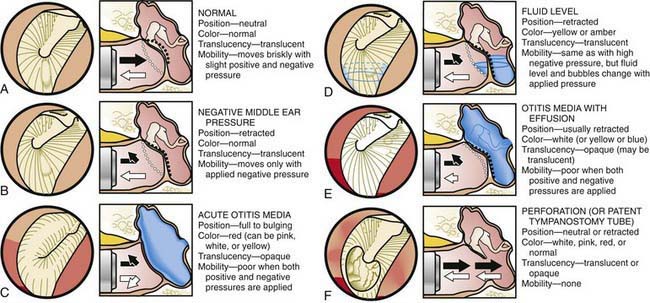

The normal TM has a silvery-gray, “waxed paper” appearance (Fig. 628-2). A white or yellow TM can indicate a middle-ear effusion. A red TM alone might not indicate pathology, because the blood vessels of the membrane may be engorged as a result of crying, sneezing, or nose blowing. A normal TM is translucent, allowing the observer to visualize the middle-ear landmarks: incus, promontory, round window niche, and, often, the chorda tympani nerve. If a middle-ear effusion is present, an air-fluid level or bubbles may be visible (see Fig. 628-2). Inability to visualize the middle-ear structures indicates opacification of the drum, usually caused by thickening of the TM, a middle-ear effusion, or both. Assessment of the light reflex often is not helpful, because a middle ear with effusion reflects light as well as a normal ear.

Figure 628-2 A-F, Common conditions of the middle ear, as assessed with the otoscope.

(From Bluestone CD, Klein JO: Otitis media in infants and children, ed 3, Philadelphia, 2001, WB Saunders, p 131.)

TM mobility is helpful in assessing middle ear pressures and the presence or absence of fluid (see Fig. 628-2). To best perform pneumatic otoscopy, a speculum of adequate size is used to obtain a good seal and allow air movement in the canal. A rubber ring around the tip of the speculum can help to obtain a better canal seal. Normal middle-ear pressure is characterized by a neutral TM position and brisk TM movement to both positive and negative pressures.

Eardrum retraction is most common when negative middle-ear pressure is present; with even moderate negative middle-ear pressure there is no visible inward movement with applied positive pressure in the ear canal (see Fig. 628-1). However, negative canal pressure, which is produced by releasing the rubber bulb of the pneumatic otoscope, can cause the TM to bounce out toward the neutral position. The TM can retract in both the presence and absence of middle-ear fluid, and if the middle-ear fluid is mixed with air, the TM might still have some mobility. Outward eardrum movement is less likely in the presence of severe negative middle-ear pressure or middle-ear effusion.

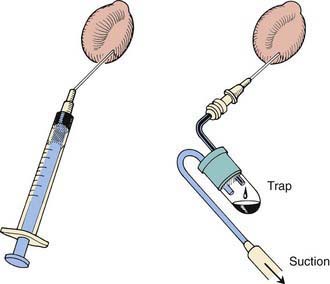

Tympanocentesis, or aspiration of the middle ear, is the definitive method of verifying the presence and type of a middle-ear effusion and is performed by inserting, through the inferior portion of the TM, an 18-gauge spinal needle attached to a syringe or a collection trap (Fig. 628-3). Culturing of the ear canal and alcohol cleansing should precede tympanocentesis and culture of the middle-ear aspirate; a canal culture is taken first to help determine whether organisms cultured from the middle ear are contaminants from the external canal or true middle ear pathogens.

Further diagnostic studies of the ear and hearing include audiometric evaluation, impedance audiometry (tympanometry), acoustic reflectometry, and specialized eustachian tube function studies. Diagnostic imaging studies, including CT and MRI, often provide further information about anatomic abnormalities and the extent of inflammatory processes or neoplasms. Specialized assessment of labyrinthine function should be considered in the evaluation of a child with a suspected vestibular disorder (Chapter 633).

Johnson KC. Audiologic assessment of children with suspected hearing loss. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2002;35:711-732.

McDivitt K. The pediatric tympanic membrane: see it, describe it, treat it. ORL Head Neck Nurs. 2003;21:14-17.

Neilan RE, Roland PS. Otalgia. Med Clin North Am. 2010;94:961-971.

Rothman R, Owens T, Simel DL. Does this child have acute otitis media? JAMA. 2003;290:1633-1640.

Shaikh N, Hoberman A, Kaleida PH, et al. Videos in clinical medicine. Diagnosing otitis media–otoscopy and cerumen removal. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:e62.