Chapter 2 General Approach to Trauma Patients

3 How is the airway managed in trauma patients?

Airway management is discussed thoroughly in Chapter 14, but trauma patients can pose a unique set of airway management challenges. Maxillofacial, laryngotracheal, and neck injury; intracranial hypertension; hemodynamic instability; thermal injury to the airway; and the need for maintaining in-line cervical spine stabilization are common conditions that can complicate airway management in trauma.

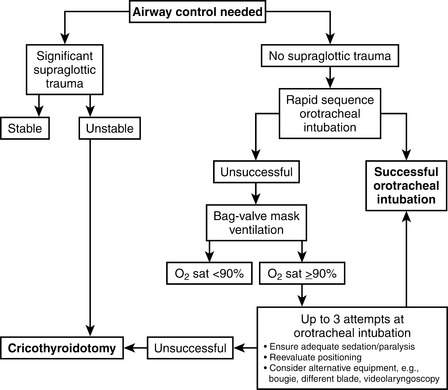

All trauma care providers should have experience with airway evaluation and management from manual airway maneuvers (e.g., jaw thrust, chin lift), to the use of mechanical airway devices (oropharyngeal and nasopharyngeal airways), to bag-mask ventilation, to rapid-sequence endotracheal intubation, to the use of airway adjuncts such as the bougie or laryngeal mask airway, to establishing a surgical airway. A general algorithm for trauma airway management is shown in Figure 2-1.

6 What is the role of the FAST examination in evaluating the trauma patient with hemodynamic instability?

14 How is closed-head injury managed?

The following are the key management principles for patients with closed-head injury:

15 What are the options for treating massive bleeding from pelvic fractures?

Pelvic immobilization, which can be temporarily obtained in the trauma bay by wrapping the pelvis with a sheet, but is definitively achieved by surgical internal or external fixation.

Preperitoneal pelvic packing, a damage control technique in which the extraperitoneal pelvis is packed with laparotomy pads to compress bleeding vessels. These are removed at a second operation when bleeding is controlled.

Angiographic embolization, which can directly address pelvic arterial bleeding and may help to stop venous bleeding by reducing pelvic vascular inflow.

16 When is chemical deep venous thrombosis (DVT) prophylaxis safe in traumatically injured patients?

Key Points General approach to trauma patients

1. Untreated airway compromise is a major cause of preventable death in trauma. Secure the airway early.

2. Bleeding is the most common cause of hypotension in the trauma patient.

3. Sources of major bleeding can be identified within minutes in the emergency department by using a combination of physical examination, bedside ultrasound scan, and radiographs.

4. In the bleeding patient, fluid infusion should be minimized until control of hemorrhage is obtained.

5. Massively bleeding patients should undergo transfusion by use of a protocol with a fixed ratio of FFP to PRBC to platelets.

1 Alam H.B. Advances in resuscitation strategies. Int J Surg. 2011;9:5–12.

2 American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma. Advanced Trauma Life Support Course Manual, 8th ed. Chicago: American College of Surgeons; 2008.

3 An G., West M.A. Abdominal compartment syndrome: a concise clinical review. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:1304–1310.

4 Bickell W.H., Wall M.J.Jr. Pepe PE, et al: Immediate versus delayed fluid resuscitation for hypotensive patients with penetrating torso injuries. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:1105–1109.

5 Bracken M.B., Shepard M.J., Holford T.R., et al. Administration of methylprednisolone for 24 or 48 hours or tirilazad mesylate for 48 hours in the treatment of acute spinal cord injury. Results of the Third National Acute Spinal Cord Injury Randomized Controlled Trial. National Acute Spinal Cord Injury Study. JAMA. 1997;277:1597–1604.

6 Brain Trauma Foundation. American Association of Neurological Surgeons; Congress of Neurological Surgeons: Guidelines for the management of severe traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2007;24(1 Suppl):S1–106.

7 Burlew C.C., Moore E.E., Smith W.R., et al. Preperitoneal pelvic packing/external fixation with secondary angioembolization: optimal care for life-threatening hemorrhage from unstable pelvic fractures. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;212:628–635. discussion 635-637

8 Cooper D.J., Rosenfeld J.V., Murray L., et alDECRA Trial Investigators. Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society Clinical Trials Group: Decompressive craniectomy in diffuse traumatic brain injury. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1493–1502.

9 Geerts W.H., Bergqvist D., Pineo G.F., et alAmerican College of Chest Physicians. Prevention of venous thromboembolism: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th ed). Chest. 2008;133(6 Suppl):381S–453S.

10 Gruen R.L., Jurkovich G.J., McIntyre L.K., et al. Patterns of errors contributing to trauma mortality: lessons learned from 2,594 deaths. Ann Surg. 2006;244:371–380.

11 Langeron O., Birenbaum A., Amour J. Airway management in trauma. Minerva Anestesiol. 2009;75:307–331.

12 Lee J.C., Peitzman A.B. Damage-control laparotomy. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2006;12:346–350.

13 Patel N.Y., Riherd J.M. Focused assessment with sonography for trauma: methods, accuracy, and indications. Surg Clin North Am. 2011;91:195–207.

14 Sanddal T.L., Esposito T.J., Whitney J.R., et al. Analysis of preventable trauma deaths and opportunities for trauma care improvement in Utah. J Trauma. 2011;70:970–977.

15 Schoenfeld A.J., Bono C.M., McGuire K.J., et al. Computed tomography alone versus computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging in the identification of occult injuries to the cervical spine: a meta-analysis. J Trauma. 2010;68:109–113.

16 Seamon M.J., Feather C., Smith B.P., et al. Just one drop: the significance of a single hypotensive blood pressure reading during trauma resuscitations. J Trauma. 2010;68:1289–1294.