General Approach to the Pediatric Patient

Perspective

Emergency medicine providers should be comfortable assessing and treating pediatric patients from the newly born through adolescence. Of the 124 million annual U.S. emergency visits, 23 million are for children younger than 15 years.1 Twenty percent of children have at least one emergency department visit per year.2 The age group with the highest emergency department use per capita is infants, with 85.5 visits per 100 infants.1 Although some hospitals have separate pediatric emergency departments, most pediatric patients are seen in general emergency departments. Several recent surveys found that more than 80% of pediatric patients are seen in general emergency departments.3,4 Therefore, all emergency providers need to be prepared to provide definitive treatment for many pediatric illnesses and injuries and to provide initial stabilization and treatment to critically ill and injured pediatric patients.

Distinguishing Principles of Disease

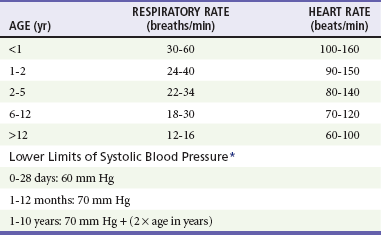

In most patients, the first step in assessment is a review of vital signs. Normal ranges for vital signs vary significantly by age. Early recognition of abnormal vital signs will help the emergency provider detect physiologic decompensation in its earliest stages. Normal vital signs by age are listed in Table 166-1. Abnormal vital signs should be repeated, and persistently abnormal vital signs should not be ignored.

Table 166-1

*From American Heart Association Emergency Cardiovascular Care (ECC) Guidelines, 2000.

From Dieckmann R, Brownstein D, Gausche-Hill M (eds): Pediatric Education for Prehospital Professionals. Sudbury, Mass, Jones & Bartlett, 2000, pp 43-45.

Airway

The pediatric airway differs in a number of ways from an adult airway.5 Numerous characteristics of the pediatric airway predispose to obstruction. Infants and young children have relatively large tongues, which may lead to airway obstruction during seizures or periods of altered mental status. Use of nasopharyngeal airways can be helpful in bypassing obstruction due to a relatively large tongue. The small airways of children are more easily obstructed with secretions. In addition, young infants preferentially breathe through their noses and can have significant respiratory distress from nasal secretions. For these reasons, airway suctioning can dramatically diminish an infant’s work of breathing. Infants and young children also have large occiputs, causing neck flexion and potential airway obstruction in the supine position. A shoulder roll can be used to properly position young patients; it may significantly decrease respiratory distress and improve intubating conditions (Fig. 166-1).

Immunologic

Young infants are at increased risk of serious bacterial infections because of their immature immune system. Febrile infants younger than 1 month are an especially high-risk group and have an approximately 10% rate of serious bacterial infection.6 For this reason, the evaluation of infants with fever differs from the evaluation of older children and adults, and the workup varies by the age and vaccination status of the infant.

Pharmacologic

Pediatric patients are particularly prone to medication errors for multiple reasons, including the fact that medications for children are calculated using weight-based dosing with attention to the adult maximum medication dose.7 Most calculation-based dosing errors occur in pediatric patients.7 Suggested safeguards include pharmacy review of medication orders, computerized order entry and use of templated order forms, resuscitation calculators, and length-based resuscitation tapes. One easily remedied potential error is the inadvertent calculation of a drug dose on the basis of weight in pounds, not kilograms, leading to a more than twofold overdose. For this reason, emergency department scales should be programmed to report weight in kilograms, not pounds, and weight in pounds should not be written in the medical chart.

Developmental

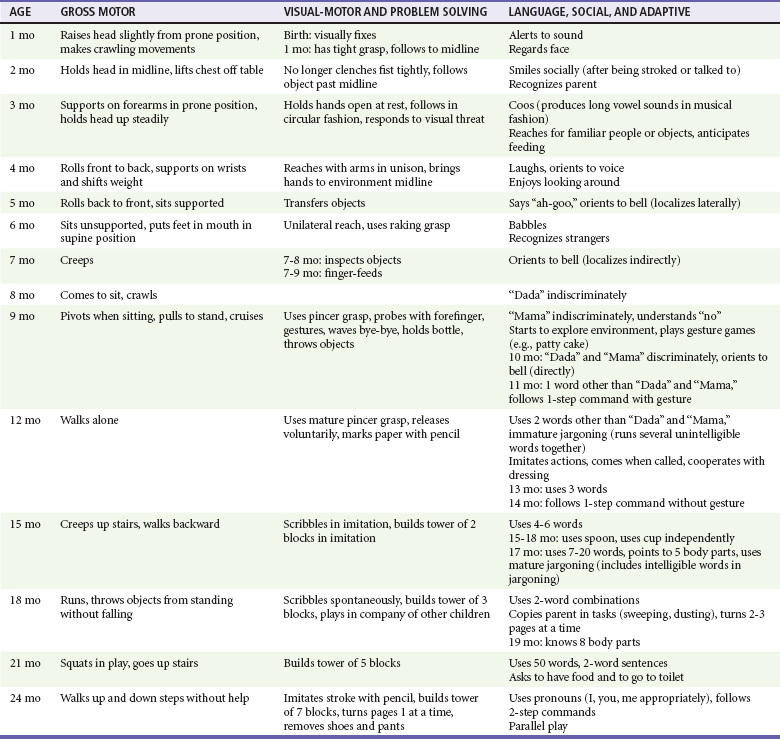

Assessment of pediatric patients requires some understanding of normal developmental milestones. Table 166-2 lists basic developmental milestones in the first 2 years of life. There will be variation in the rate at which children develop. Therefore, the parent’s report of the child’s developmental history and normal behavior is extremely important.

Table 166-2

Developmental Milestones in Children Younger Than 2 Years

Modified from Gunn KL, Nechyba C (eds): The Harriet Lane Handbook, 16th ed. St Louis, CV Mosby, 2003.

Evaluation

Triage systems with pediatric modifications include the Emergency Severity Index, the pediatric Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale, the Manchester Triage System, and the Australasian Triage Scale.8 All of these systems are five-level triage systems. In five-level triage systems, level 1 patients require immediate intervention. Level 2 patients are emergent and should be seen within 10 to 15 minutes. Level 3 patients are considered urgent and should be seen within 30 to 60 minutes, depending on the triage system. Level 4 and level 5 are thought to be stable patients. The Emergency Severity Index classifies patients by acuity and number of resources expected to be required.9 A flowchart specific to pediatric patients with fever has been added. In the Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale, specific criteria for various presenting complaints are used to assign triage levels.10 The pediatric modification includes pediatric-specific presenting complaints and determination of acuity by use of pediatric-specific vital signs. The Manchester Triage System contains flowcharts based on presenting complaint, with some pediatric-specific flowcharts.11 The Australasian Triage Scale is mostly a general triage scale but has several pediatric-specific criteria.12

No triage system is clearly demonstrated to be superior, and data on reliability and validity are limited for all triage systems. The Emergency Severity Index, the Manchester Triage System, and the pediatric Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale have been demonstrated to be valid in pediatric patients.8,13,14 Reliability is good for the Manchester Triage System and moderate for the Emergency Severity Index and pediatric Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale.8,14 The Australasian Triage Scale appears to have lower reliability than the other triage systems.8

History

In critically ill or injured patients, the SAMPLE history can be used as a way to quickly obtain a focused history (Box 166-1). The SAMPLE history reminds providers to ask for Signs and symptoms, Allergies, Medications, Past medical history, Last meal, and Events surrounding the illness or injury.

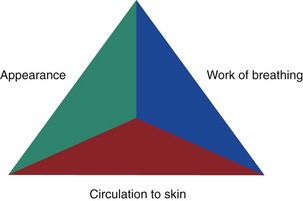

Pediatric Assessment Triangle

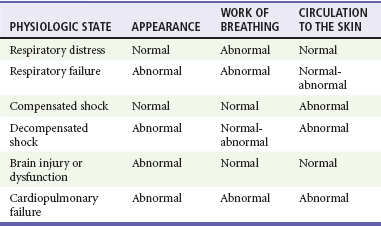

Rapid recognition of the critically ill child or the child at risk for rapid decompensation is a critical skill for the emergency medicine provider. One tool that has been developed to assist providers in quickly assessing children is the pediatric assessment triangle (PAT) (Fig. 166-2).15,16 It is an orderly approach that helps clinicians formulate an initial impression of the overall status of the child from the door of the examination room. The three components of the PAT are appearance, work of breathing, and circulation. On the basis of the initial PAT, the clinician is able to rapidly distinguish the “sick” from “well” child. Table 166-3 summarizes the findings that may be noted on each of the three arms of the triangle, and Table 166-4 summarizes the interpretation of the triangle.

Table 166-3

Pediatric Assessment Triangle Findings

| APPEARANCE | WORK OF BREATHING | CIRCULATION TO THE SKIN |

| Tone | Abnormal sounds: stridor, grunting, snoring, wheezing | Pallor |

| Irritable, interactive | Abnormal positioning: sniffing, tripoding, refusal to lie down | Mottling |

| Consolable | Retractions | Cyanosis |

| Look/gaze | Head bobbing | Petechiae |

| Speech/cry | Nasal flaring |

Modified from Dieckmann R, Brownstein D, Gausche-Hill M (eds): Pediatric Education for Prehospital Professionals. Sudbury, Mass, Jones & Bartlett, 2000, pp 36-40.

Table 166-4

Interpretation of the Pediatric Assessment Triangle

Modified from Dieckmann R, Brownstein D, Gausche-Hill M (eds): Pediatric Education for Prehospital Professionals. Sudbury, Mass, Jones & Bartlett, 2000, pp 30-57.

Figure 166-2 Pediatric assessment triangle.

Appearance.: Observation of the child from a distance allows the provider to assess the patient’s overall status without upsetting the child. The mnemonic TICLS (tone, interactiveness, consolability, look/gaze, and speech/cry) summarizes the components of the assessment of overall appearance. Observation of the infant or child interacting with his or her parents gives many clues about the child’s overall status. An infant with a vacant or glazed look can be distinguished from an alert infant who attends to environmental stimuli. An infant who is awake but lying motionless on a gurney is much more concerning than an active infant moving all extremities. Irritability is an early sign of inadequate brain perfusion. This may be followed by lethargy and then coma as the poor perfusion continues.

Work of Breathing.: The work of breathing should be observed initially from a distance because it is difficult to adequately assess work of breathing in a crying child. The position of the child can be a clue to the level of respiratory distress. Infants and children with respiratory distress may assume the sniffing position in an attempt to decrease their work of breathing. Tripoding is an ominous sign of severe respiratory distress.

For adequate assessment for the presence of retractions and abdominal breathing, the infant or young child will ideally be observed without a shirt. Retractions may be seen in the suprasternal, supraclavicular, intercostal, and subcostal areas and are indicative of increased work of breathing (Fig. 166-3). Nasal flaring is an attempt to decrease airway resistance and is a sign of severe respiratory distress (Fig. 166-4). Head bobbing occurs when infants use neck muscles to assist respiration and is another sign of severe respiratory distress. Seesaw breathing, an ineffective breathing pattern in which the abdomen moves outward and the chest moves inward during inspiration, is a sign of impending respiratory failure. As the child tires and nears complete respiratory failure, the respiratory rate can fall and the work of breathing may be diminished.

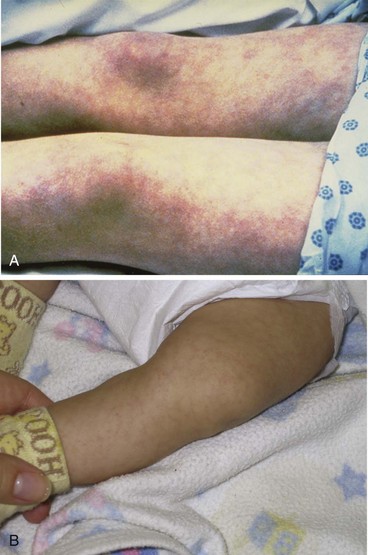

Circulation.: Visual inspection of the skin can provide clues to the overall cardiovascular status. Early compensated shock is characterized by peripheral vasoconstriction and shunting of blood to the brain and other vital organs. At this stage, pallor may be appreciated. If the shock state is not corrected, the patient may become mottled (Fig. 166-5A). Mottling is a random pattern of vasoconstriction and vasodilation in adjacent areas of the skin. This may be confused with cutis marmorata, a lacy pattern on the skin caused by vascular instability (Fig. 166-5B). Cutis marmorata is a normal finding in young infants in cool environments. In contrast to infants with mottling, infants with cutis marmorata will be otherwise well appearing, and the skin findings will diminish or disappear if the infant is bundled or placed in a warm environment. Cyanosis may be present normally in children with congenital heart disease, but if cyanosis is a new finding for the patient, it is indicative of respiratory failure or decompensated shock.

Physical Examination

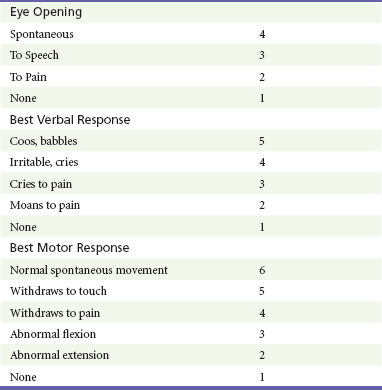

The Glasgow Coma Scale is a useful way to objectively document the mental status examination and serves as an easy way to communicate the mental status to other providers. The pediatric modification for the Glasgow Coma Scale is shown in Table 166-5. A less comprehensive way to communicate the mental status is AVPU, or Alert, responsive to Verbal commands, responsive to Painful stimuli, or Unresponsive.

Table 166-5

Glasgow Coma Scale Modified for Preverbal Pediatric Patients*

*Total score key: severe, <9; moderate, 9-13; mild, 14-15.

Modified from James HE: Neurologic evaluation and support in the child with an acute brain insult. Pediatric Ann 15:16-22, 1986.

As in adults, the physical examination in critically ill or injured children will focus initially on airway, breathing, and circulation with correction of abnormalities in these systems before a complete physical examination is performed. In less critically ill infants and young children, auscultation of the heart and lungs should be performed before proceeding to frightening or uncomfortable parts of the examination. In general, the ears and oropharynx should be examined last because many children will cry, making the remainder of the physical examination difficult. Parents can hold frightened young children for ear examinations by holding the child in the lap with one arm around the head and one arm around the child’s body and arms (Fig. 166-6). This allows the child to be held by the parent during an unpleasant part of the examination while having the head and arms adequately restrained to allow visualization of the tympanic membranes and avoidance of injury. When necessary, external examination of the vagina in young girls can be facilitated by having them sit in a frog-leg position in the parent’s lap.

Specific Disorders

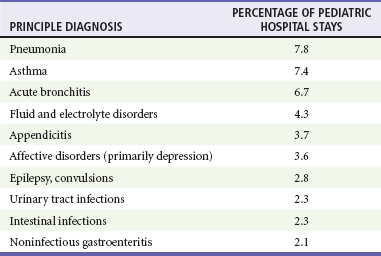

Fortunately, most pediatric visits to the emergency department are for minor illnesses and injuries, but emergency medicine providers needs to be prepared to care for critically ill and injured children as well. The most common reasons for infants and children to be seen in emergency departments are respiratory illness, fever, and injury.17 Table 166-6 lists the most common emergency department diagnoses for infants and children in California, and Table 166-7 lists the most common reasons for hospitalization of pediatric patients in the United States. Causes of serious illness and injury vary by age. Respiratory illnesses are the most common causes of infant hospitalization after the immediate neonatal period.18 Asthma and appendicitis are the most common reasons for hospitalization of school-age children, and affective disorders are the most common cause of adolescent hospitalizations.

Table 166-6

Top Five Emergency Department Diagnoses by Age in California

| INFANTS YOUNGER THAN 1 YEAR | CHILDREN 1-17 YEARS |

| Acute upper respiratory infection | Acute upper respiratory infection |

| Fever | Otitis media |

| Otitis media | Open wounds of head |

| Unspecified viral and chlamydial infections | Contusions |

| Pneumonia | Upper extremity fractures |

Modified from McConville S, Lee H: Emergency department care in California. Who uses it and why? California Counts Population Trends and Profiles 10:1-23, 2008.

Table 166-7

Top 10 Reasons for Pediatric Hospitalization (Excluding Neonatal and Maternity Care)

Modified from Owens PL, Thompson J, Elixhauser A, Ryan K: Care of Children and Adolescents in U.S. Hospitals. HCUP Fact Book No. 4. AHRQ Publication No. 04-0004. Rockville, Md, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2003. Available at www.ahrq.gov/data/hcup/factbl4/. Accessed April 2011.

Children with Special Health Care Needs

However, relying on the parent’s knowledge and recollection of detailed medical information can be a problem, especially during times of high stress. Parents may forget medication names or concentrations. One solution is the use of an Emergency Information Form (EIF) for children with special health care needs.19 The form summarizes chronic medical conditions, medications, medical devices, and other critical information and is available at www.aap.org/advocacy/blankform.pdf. When they are accessible, these forms can quickly provide critical information to the emergency department provider, assisting in the early management and stabilization of the child until more detailed records are accessed or the specialist is contacted. Emergency departments can request that specialists affiliated with their hospitals provide EIFs for complex patients to facilitate rapid and appropriate emergency treatment.

Altered Mental Status

Although many of the possible causes of altered mental status are the same in adults and children, a few considerations in the differential are unique to pediatrics. A mnemonic for causes of altered mental status in children is AEIOUTIPS (Box 166-2). The postictal state, central nervous system infection, and ingestions cause altered mental status in both adults and children. However, child abuse, intussusception, and inborn errors of metabolism are pediatric-specific causes of altered mental status that should also be considered.

Seizures

Febrile seizures are another diagnosis unique to pediatrics. Simple febrile seizures are brief generalized seizures occurring no more often than once in a 24-hour period in children between the ages of 6 months and 5 years. Simple febrile seizures require no specific treatment and in an otherwise well-appearing, vaccinated child do not by themselves necessitate further workup.20

Trauma

Pediatric patients with blunt trauma have injury patterns different from those of adults. Children have relatively large heads in relation to their bodies, predisposing them to head trauma. They also have relatively elastic cervical spines and can have spinal cord injuries without radiologic evidence of injury. Therefore, any history of paresthesias, weakness, or other neurologic symptoms necessitates further investigation even if symptoms have resolved by the time of emergency department evaluation. Traumatic aortic injuries are less common in children than in adults.21 In children with tension pneumothorax, the mediastinum is more mobile, resulting rapidly in an obstructive form of shock. Children have less intraperitoneal fat than adults do, and their solid abdominal organs are relatively large compared with the abdominal cavity, predisposing to splenic and liver lacerations. The kidneys lack perirenal fat and are relatively mobile, predisposing to renal trauma. The bladder is an abdominal organ and is less protected by the pelvis in young children.

Child Abuse

Nonaccidental trauma should be a consideration for all patients presenting with injuries or with certain otherwise unexplained medical complaints, such as altered mental status and apparent life-threatening events. Many children with abusive injuries are not diagnosed as being the victims of abuse at initial health care encounters, leaving them at risk for more serious injuries and death.22,23 Historical clues to nonaccidental trauma include a mechanism inconsistent with the injury and a history inconsistent with the developmental level of the child (Box 166-3). Physical examination clues to abuse include bruises in young infants and bruises on certain areas of the body, such as the ear and trunk24 (Box 166-4). Fractures in children younger than 18 months without a significant witnessed trauma mechanism are especially concerning.25

The Pediatric-Ready Emergency Department

Preparation to care for infants and children of all ages requires not only emergency department staff training but also pediatric medication formulations, intravenous fluids, and equipment and supplies in sizes appropriate for the premature neonate to the large adolescent. The American College of Emergency Physicians, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Emergency Nurses Association developed joint guidelines for care of children in the emergency department.26,27 The guidelines include recommendations on necessary personnel, protocols, medications, equipment, and supplies. Surveys have found that emergency departments frequently lack items recommended in the guidelines.3,28 One strong recommendation in the guidelines is the appointment of physician and nurse coordinators of pediatric emergency care.26,27

The Pediatric-Friendly Emergency Department

One topic that has received increasing attention in recent years is pain and anxiety management in pediatric patients. Procedural pain is frequently undertreated in infants.29,30 Appropriate use of sedation, anesthesia, analgesia, and nonpharmacologic methods of pain management can increase the patient’s cooperation and increase visit satisfaction for the child and parent. Children have significant anxiety and fear surrounding medical procedures, leading to additional challenges in successful performance of procedures. In addition to reducing pain and anxiety in the acute visit, adequate pain control is likely to have long-term benefits. Multiple studies have demonstrated that inadequate pain control can have long-term deleterious consequences, leading to increased pain perception with future painful procedures.31

A variety of options are available to minimize pain associated with drawing of blood and starting of intravenous lines, including vapocoolants, topical anesthetics, and needle-free jet injection of anesthetics.32 Topical anesthetics can also decrease the pain of anesthetic injection before lumbar puncture and other procedures. Topical application of a lidocaine, epinephrine, and tetracaine mixture has been shown to have comparable efficacy to injected anesthesia for facial and scalp lacerations.33 Oral sucrose seems to decrease procedural pain in neonates.34 Nonpharmacologic distraction techniques such as bubbles, songs, books, videos, and videogames can be used to decrease anxiety.31 In children, the use of anxiolytic medications or procedural sedation may be appropriate for procedures that could be accomplished with local anesthesia in more mature patients.

Another shift in recent years is increased support for family presence during invasive procedures and resuscitations.35–37 Children are stressed when they are separated from parents, and one benefit of family presence is that parents are able to reassure and calm the child.38 Studies have shown that family presence also decreases anxiety levels in family members.39 Presence during unsuccessful cardiopulmonary resuscitation is perceived by families as beneficial in the grieving process.40 Studies have shown that with well-implemented policies, family presence does not interfere with resuscitation.41

Families present during resuscitations should have a family support person assigned who can explain procedures and answer questions. A social worker, chaplain, or nurse could fulfill this role. Ideally, families are briefed on what to expect before entering the resuscitation room. Guidelines have been developed to assist emergency department providers in implementing family presence protocols at their institutions.38

References

1. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, Division of Data Services. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2008 Emergency Department Summary Tables. www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ahcd/nhamcs_emergency/nhamcsed2008.pdf.

2. Garcia, TC, Bernstein, AB, Bush, MA. Emergency Department Visitors and Visits: Who Used the Emergency Room in 2007? NCHS Data Brief, No 38. Huntsville, Md: National Center for Health Statistics; 2010.

3. Gausche-Hill, M, Schmitz, C, Lewis, RJ. Pediatric preparedness of US emergency departments: A 2003 survey. Pediatrics. 2007;120:1229–1237.

4. Niska, R, Bhuiya, F, Xu, J. National hospital ambulatory medical care survey: 2007 emergency department summary. Natl Health Stat Report. 2010;26:1–31.

5. Santillanes, G, Gausche-Hill, M. Pediatric airway management. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2008;26:961–975.

6. Huppler, AR, Eickhoff, JC, Wald, ER. Performance of low-risk criteria in the evaluation of young infants with fever. Pediatrics. 2010;125:228–233.

7. Kozer, E, Berkovitch, M, Koren, G. Medication errors in children. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2006;53:1155–1168.

8. van Veen, M, Moll, HA. Reliability and validity of triage systems in pediatric emergency care. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2009;17:38.

9. Gilboy, N, Tanabe, T, Travers, D, Rosenau, AM, Emergency Severity Index (ESI): A Triage Tool for Emergency Department Care, Version 4. Implementation Handbook 2012 Edition. AHRQ Publication No. 12-0014. Rockville, Md:Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2011. www.ahrq.gov/research/esi/esihandbk.pdf.

10. Murray, M, Bullard, M, Grafstein, E. Revisions to the Canadian Emergency Department Triage and Acuity Scale implementation guidelines. CJEM. 2004;6:421–427.

11. Mackway-Jones, K, Marsden, J, Windle, J. Emergency Triage, Manchester Triage Group, 2nd ed. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing; 2006.

12. Australian Government, Department of Health and Ageing, Emergency Triage Education Kit. Commonwealth of Australia; 2009. www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/5E3156CFFF0A34B1CA2573D0007BB905/$File/Triage%20Education%20Kit.pdf.

13. Durani, Y, Brecher, D, Walmsley, D, Attia, MW, Loiselle, JM. The emergency severity index version 4: Reliability in pediatric patients. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2009;25:751–753.

14. Travers, DA, Waller, AE, Katznelson, J, Agans, R. Reliability and validity of the emergency severity index for pediatric triage. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16:843–849.

15. Dieckmann, R, Brownstein, D, Gausche-Hill, M. Pediatric Education for Prehospital Professionals. Sudbury, Mass: Jones & Bartlett; 2000.

16. Dieckmann, RA, Brownstein, D, Gausche-Hill, M. The pediatric assessment triangle: A novel approach for the rapid evaluation of children. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2010;26:312–315.

17. McConville, S, Lee, H. Emergency department care in California? Who uses it and why? California Counts Population Trends and Profiles. 2008;10:1–23.

18. Owens, PL, Thompson, J, Elixhauser, A, Ryan, K, Care of Children and Adolescents in U.S. Hospitals. HCUP Fact Book No. 4. AHRQ Publication No. 04-0004. Rockville, Md:Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2003. www.ahrq.gov/data/hcup/factbl4/.

19. American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Pediatric Emergency Medicine and Council on Clinical Information Technology, American College of Emergency Physicians, Pediatric Emergency Medicine Committee. Policy statement—emergency information forms and emergency preparedness for children with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 2010;125:829–837.

20. Subcommittee on Febrile Seizures, American Academy of Pediatrics. Neurodiagnostic evaluation of the child with a simple febrile seizure. Pediatrics. 2011;127:389–394.

21. Anderson, SA, Day, M, Chen, MK, Huber, T. Traumatic aortic injuries in the pediatric population. J Pediatr Surg. 2008;43:1077–1081.

22. Ravichandiran, N, et al. Delayed identification of pediatric abuse-related fractures. Pediatrics. 2010;125:60–66.

23. Trokel, M, Waddimba, A, Griffith, J, Sege, R. Variation in the diagnosis of child abuse in severely injured infants. Pediatrics. 2006;117:722–728.

24. Pierce, MC, Kaczor, K, Aldridge, S, O’Flynn, J, Lorenz, DJ. Bruising characteristics discriminating physical child abuse from accidental trauma. Pediatrics. 2010;125:67–74.

25. Kemp, A, et al. Patterns of skeletal fractures in child abuse: Systematic review. BMJ. 2008;337:a1518.

26. American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Pediatric Emergency Medicine, American College of Emergency Physicians Pediatric Committee, Emergency Nurses Association Pediatric Committee. Joint policy statement—guidelines for care of children in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54:543–552.

27. American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Pediatric Emergency Medicine, American College of Emergency Physicians Pediatric Committee, Emergency Nurses Association Pediatric Committee. Joint policy statement—guidelines for care of children in the emergency department. Pediatrics. 2009;124:1233–1243.

28. Middleton, KR, Burt, CW. Availability of pediatric services and equipment in emergency departments: United States, 2002-2003. Adv Data. 2006;367:1–16.

29. Hoyle, JD, Jr., Rogers, AJ, Reischman, DE, Powell, EC, et al. Pain intervention for infant lumbar puncture in the emergency department: Physician practice and beliefs. Acad Emerg Med. 2011;18:140–144.

30. Fein, D, Avner, JR, Khine, H. Pattern of pain management during lumbar puncture in children. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2010;26:357–360.

31. Khan, KI, Wiesman, SJ. Nonpharmacologic pain management strategies in the pediatric emergency department. Clin Pediatr Emerg Med. 2007;8:240–247.

32. Young, KD. What’s new in topical anesthesia? Clin Pediatr Emerg Med. 2007;8:232–239.

33. Ferguson, C, Loryman, B, Body, R. Best evidence topic report. Topical anaesthetic versus lidocaine infiltration to allow closure of skin wounds in children. Emerg Med J. 2005;22:507–509.

34. Stevens, B, Yamada, J, Ohlsson, A. Sucrose for analgesia in newborn infants undergoing painful procedures. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (1):2010.

35. Henderson, DP, Knapp, JF. Report of the national consensus conference of family presence during pediatric cardiopulmonary resuscitation and procedures. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2005;21:878–891.

36. O’Malley, P, Brown, K, Mace, SE. Patient- and family-centered care and the role of the emergency physician providing care to a child in the emergency department. Pediatrics. 2006;118:2242–2244.

37. Dingeman, RS, Mitchell, EA, Meyer, EC, Curley, MA. Parent presence during complex invasive procedures and cardiopulmonary resuscitation: A systematic review of the literature. Pediatrics. 2007;120:842–854.

38. Farah, MM, Thomas, CA, Shaw, KN. Evidence-based guidelines for family presence in the resuscitation room. A step-by-step approach. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2007;23:587–591.

39. Nishisaki, A, Diekema, DS. Mind the gap and narrowing it: Family presence during pediatric resuscitation and invasive procedures. Resuscitation. 2011;82:655–656.

40. Tinsley, C, Hill, JB, Shah, J, Zimmerman, G. Experience of families during cardiopulmonary resuscitation in a pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatrics. 2008;122:e799–e804.

41. Dudley, NC, et al. The effect of family presence on the efficiency of pediatric trauma resuscitations. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;53:777–784.