Chapter 1 General Appearance, Facies, and Body Habitus

General Appearance

2 Which aspects of the patient should be assessed?

A. Posture

3 What information can be obtained from observing the patient’s posture?

In abdominal pain the posture is often so typical as to localize the disease:

Patients with pancreatitis usually lie in the fetal position: on one side, with knees and legs bent over.

Patients with pancreatitis usually lie in the fetal position: on one side, with knees and legs bent over.

Patients with peritonitis are very still and avoid any movement that might worsen the pain.

Patients with peritonitis are very still and avoid any movement that might worsen the pain.

Patients with intestinal obstruction are instead quite restless.

Patients with intestinal obstruction are instead quite restless.

Patients with renal or perirenal abscesses bend toward the side of the lesion.

Patients with renal or perirenal abscesses bend toward the side of the lesion.

Patients who lie supine, with one knee flexed and the hip externally rotated, are said to have the “psoas sign.” This reflects either a local abnormality around the iliopsoas muscle (such as an inflamed appendix, diverticulum, or terminal ileum from Crohn’s disease) or inflammation of the muscle itself. In the olden days, the latter was due to a tuberculous abscess, originating in the spine and spreading down along the muscle. Such processes were referred to as “cold abscesses” because they had neither warmth nor other signs of inflammation. Now, the most common cause of a “psoas sign” is intramuscular bleeding from anticoagulation.

Patients who lie supine, with one knee flexed and the hip externally rotated, are said to have the “psoas sign.” This reflects either a local abnormality around the iliopsoas muscle (such as an inflamed appendix, diverticulum, or terminal ileum from Crohn’s disease) or inflammation of the muscle itself. In the olden days, the latter was due to a tuberculous abscess, originating in the spine and spreading down along the muscle. Such processes were referred to as “cold abscesses” because they had neither warmth nor other signs of inflammation. Now, the most common cause of a “psoas sign” is intramuscular bleeding from anticoagulation.

Patients with meningitis lie like patients with pancreatitis: on the side, with neck extended, thighs flexed at the hips, and legs bent at the knees—juxtaposed like the two bores of a double-barreled rifle.

Patients with meningitis lie like patients with pancreatitis: on the side, with neck extended, thighs flexed at the hips, and legs bent at the knees—juxtaposed like the two bores of a double-barreled rifle.

Patients with a large pleural effusion tend to lie on the affected side to maximize excursions of the unaffected side. This, however, worsens hypoxemia (see Chapter 13, questions 48–51).

Patients with a large pleural effusion tend to lie on the affected side to maximize excursions of the unaffected side. This, however, worsens hypoxemia (see Chapter 13, questions 48–51).

Patients with a small pleural effusion lie instead on the unaffected side (because direct pressure would otherwise worsen the pleuritic pain).

Patients with a small pleural effusion lie instead on the unaffected side (because direct pressure would otherwise worsen the pleuritic pain).

Patients with a large pericardial effusion (especially tamponade) sit up in bed and lean forward, in a posture often referred to as “the praying Muslim position.” Neck veins are greatly distended.

Patients with a large pericardial effusion (especially tamponade) sit up in bed and lean forward, in a posture often referred to as “the praying Muslim position.” Neck veins are greatly distended.

Patients with tetralogy of Fallot often assume a squatting position, especially when trying to resolve cyanotic spells—such as after exercise.

Patients with tetralogy of Fallot often assume a squatting position, especially when trying to resolve cyanotic spells—such as after exercise.

4 What is the posture of patients with dyspnea?

An informative alphabet soup of orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, platypnea and orthodeoxia, trepopnea, respiratory alternans, and abdominal paradox. These can determine not only the severity of dyspnea, but also its etiology (see Chapter 13, questions 35–51).

B. State of Hydration

5 What is hypovolemia?

A condition characterized by volume depletion and dehydration:

Volume depletion is a loss in extracellular salt, through either kidneys (diuresis) or the gastrointestinal tract (hemorrhage, vomiting, diarrhea). This causes contraction of the total intravascular pool of plasma, which results in circulatory instability and thus an increase in the serum urea nitrogen-to-creatinine ratio—a valuable biochemical marker for volume depletion.

Volume depletion is a loss in extracellular salt, through either kidneys (diuresis) or the gastrointestinal tract (hemorrhage, vomiting, diarrhea). This causes contraction of the total intravascular pool of plasma, which results in circulatory instability and thus an increase in the serum urea nitrogen-to-creatinine ratio—a valuable biochemical marker for volume depletion.

Dehydration is instead a loss of intracellular water. It eventually causes cellular desiccation and an increase in serum sodium and plasma osmolality, two useful biochemical markers.

Dehydration is instead a loss of intracellular water. It eventually causes cellular desiccation and an increase in serum sodium and plasma osmolality, two useful biochemical markers.

9 How do you determine the presence of hypovolemia?

Through the “tilt test,” which measures postural changes in heart rate and blood pressure (BP):

1. Ask the patient to lie supine.

3. Measure heart rate and blood pressure in this position.

6. Measure heart rate and then blood pressure while the patient is standing. Measure rate by counting over 30 seconds and multiplying by two, which is more accurate than counting over 15 seconds and multiplying by four.

12 Should the patient lie supine for more than 2 minutes before standing up?

No. A longer period does not increase the sensitivity of the test.

14 What is the normal response to the tilt test?

Going from supine to standing, a normal patient exhibits the following:

18 So what are the findings of a positive tilt test for hypovolemia?

The most helpful is a postural increase in heart rate of at least 30 beats/minute (which has a sensitivity of 97% and a specificity of 96% for blood loss >630 mL). This change (as well as severe postural dizziness, see later) may last 12–72 hours if IV fluids are not administered.

The most helpful is a postural increase in heart rate of at least 30 beats/minute (which has a sensitivity of 97% and a specificity of 96% for blood loss >630 mL). This change (as well as severe postural dizziness, see later) may last 12–72 hours if IV fluids are not administered.

The second most helpful finding is postural dizziness so severe to stop the test. This has the same sensitivity and specificity as tachycardia. Mild postural dizziness, instead, has no value.

The second most helpful finding is postural dizziness so severe to stop the test. This has the same sensitivity and specificity as tachycardia. Mild postural dizziness, instead, has no value.

Hypotension of any degree while standing has little value unless associated with dizziness. In fact, an orthostatic drop in systolic BP >20 mmHg unassociated with dizziness can occur in one third of patients >65 years old and 10% of younger subjects, with or without hypovolemia.

Hypotension of any degree while standing has little value unless associated with dizziness. In fact, an orthostatic drop in systolic BP >20 mmHg unassociated with dizziness can occur in one third of patients >65 years old and 10% of younger subjects, with or without hypovolemia.

Supine hypotension (systolic BP <95 mmHg) and tachycardia (>100/min) may be absent, even in patients with blood losses >1 L. Hence, although quite specific for hypovolemia when present, supine hypotension and tachycardia have low sensitivity; they are present in one tenth of patients with moderate blood loss and in one third with severe blood loss. Paradoxically, blood-loss patients may even present with bradycardia as a result of a vagal reflex.

Supine hypotension (systolic BP <95 mmHg) and tachycardia (>100/min) may be absent, even in patients with blood losses >1 L. Hence, although quite specific for hypovolemia when present, supine hypotension and tachycardia have low sensitivity; they are present in one tenth of patients with moderate blood loss and in one third with severe blood loss. Paradoxically, blood-loss patients may even present with bradycardia as a result of a vagal reflex.

29 What is the significance of dry mucous membranes in children?

Mild depletion corresponds to <5% intravascular contraction (i.e., <50 mL/kg loss of body weight). This is usually determined by history alone, since physical signs are minimal or absent. Mucosae are moist, skin turgor and capillary refill normal, and pulse slightly increased.

Mild depletion corresponds to <5% intravascular contraction (i.e., <50 mL/kg loss of body weight). This is usually determined by history alone, since physical signs are minimal or absent. Mucosae are moist, skin turgor and capillary refill normal, and pulse slightly increased.

Moderate depletion corresponds instead to 100 mL/kg loss of body weight. Mucosae are dry, skin turgor reduced, pulses weak, and patients are tachycardic and hyperpneic.

Moderate depletion corresponds instead to 100 mL/kg loss of body weight. Mucosae are dry, skin turgor reduced, pulses weak, and patients are tachycardic and hyperpneic.

Severe depletion corresponds to >100 mL/kg loss of body weight. All previous signs are present, plus cold, dry, and mottled skin; altered sensorium; prolonged refill time; weak central pulses; and, eventually, hypotension.

Severe depletion corresponds to >100 mL/kg loss of body weight. All previous signs are present, plus cold, dry, and mottled skin; altered sensorium; prolonged refill time; weak central pulses; and, eventually, hypotension.

C. State of Nutrition

33 Why is the BMI important?

Because a high BMI is associated with increased risk for serious medical problems:

Various cancers (including endometrial, breast, prostate, and colon) are more common in obese subjects (in one study, 52% higher rates in men and 62% in women).

Various cancers (including endometrial, breast, prostate, and colon) are more common in obese subjects (in one study, 52% higher rates in men and 62% in women).

Miscellaneous conditions, such as lower extremity venous stasis, idiopathic intracranial hypertension, gastroesophageal reflux, urinary stress incontinence, gallbladder disease, osteoarthritis, sleep apnea, and respiratory problems

Miscellaneous conditions, such as lower extremity venous stasis, idiopathic intracranial hypertension, gastroesophageal reflux, urinary stress incontinence, gallbladder disease, osteoarthritis, sleep apnea, and respiratory problems

Note that body weight has a U-shaped relationship with mortality, causing an increase when either very low or very high.

Note that body weight has a U-shaped relationship with mortality, causing an increase when either very low or very high.

38 How important is the distribution of body fat?

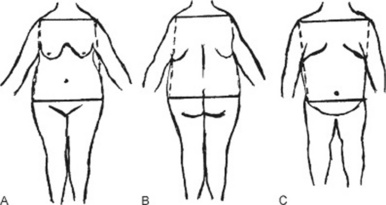

Very important, since it strongly determines the impact of obesity on health. Fat deposition may be central (mostly in the trunk) or peripheral (mostly in the extremities) (Fig. 1-1).

Central obesity has a bihumeral diameter greater than the bitrochanteric diameter; subcutaneous fat has a “descending” distribution, being mostly concentrated in the upper half of the body (neck, cheeks, shoulder, chest, and upper abdomen).

Central obesity has a bihumeral diameter greater than the bitrochanteric diameter; subcutaneous fat has a “descending” distribution, being mostly concentrated in the upper half of the body (neck, cheeks, shoulder, chest, and upper abdomen).

Peripheral obesity has instead a bitrochanteric diameter greater than the bihumeral diameter; subcutaneous fat has an “ascending” distribution, being mostly concentrated in the lower half of the body (lower abdomen, pelvic girdle, buttocks, and thighs).

Peripheral obesity has instead a bitrochanteric diameter greater than the bihumeral diameter; subcutaneous fat has an “ascending” distribution, being mostly concentrated in the lower half of the body (lower abdomen, pelvic girdle, buttocks, and thighs).

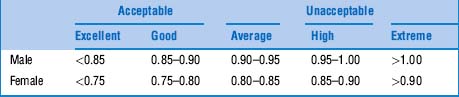

42 What is the WHR threshold for cardiovascular risk?

The cutoff seems to be a waist-to-hip ratio of 0.83 for women and 0.9 for men. Favoring WHR over BMI would result in a threefold increase in the population at risk for myocardial infarction. This would be especially valuable in Asia, where obesity by BMI is rare, but WHRs can be quite abnormal (Table 1-1).

48 What are the physical examination components of the SGA?

The best locations for assessing subcutaneous fat are the triceps regions of the arms, the midaxillary line at the costal margin, the interosseous and palmar areas of the hand, and the deltoids of the shoulder. Loss of subcutaneous fat appears as lack of fullness, with skin loosely fitting over the deeper tissues.

The best locations for assessing subcutaneous fat are the triceps regions of the arms, the midaxillary line at the costal margin, the interosseous and palmar areas of the hand, and the deltoids of the shoulder. Loss of subcutaneous fat appears as lack of fullness, with skin loosely fitting over the deeper tissues.

Muscle wasting is best assessed by palpation (although inspection may also help). Best locations for doing so are the quadriceps femoris and deltoids. Shoulders of malnourished patients appear “squared off” as a result of both muscle wasting and subcutaneous fat loss.

Muscle wasting is best assessed by palpation (although inspection may also help). Best locations for doing so are the quadriceps femoris and deltoids. Shoulders of malnourished patients appear “squared off” as a result of both muscle wasting and subcutaneous fat loss.

Loss of fluid from the intravascular to extravascular space refers primarily to ankle/sacral edema and ascites. Edema is best assessed by palpation—that is, by pressing over the ankles or sacral area. Fluid displaced from subcutaneous tissues as a result of compression is its hallmark. Such displacement is clinically manifested by a persistent depression of the compressed area (pitting), which lasts for more than 5 seconds.

Loss of fluid from the intravascular to extravascular space refers primarily to ankle/sacral edema and ascites. Edema is best assessed by palpation—that is, by pressing over the ankles or sacral area. Fluid displaced from subcutaneous tissues as a result of compression is its hallmark. Such displacement is clinically manifested by a persistent depression of the compressed area (pitting), which lasts for more than 5 seconds.

D. Facies

51 Which disease processes are associated with a typical facies?

Quite a few. The following list is not necessarily exhaustive (Table 1-2):

Facies bovina: The cowlike face of Greig’s syndrome: large cranial vault, huge forehead, high bregma, and occasional hypertelorism (widely spaced eyes)—all due to an enlarged sphenoid bone. It is often associated with other congenital deformities, such as osteogenesis imperfecta, syndactyly and polydactyly, Sprengel’s deformity (scapular elevation), and mental retardation.

Facies bovina: The cowlike face of Greig’s syndrome: large cranial vault, huge forehead, high bregma, and occasional hypertelorism (widely spaced eyes)—all due to an enlarged sphenoid bone. It is often associated with other congenital deformities, such as osteogenesis imperfecta, syndactyly and polydactyly, Sprengel’s deformity (scapular elevation), and mental retardation.

Elfin face: An unusually flat face, with broad forehead, hypertelorism, short and upturned nose, low-set ears that are posteriorly rotated, puffy cheeks, wide mouth, patulous lips, hypoplastic teeth, and a deep husky voice. Patients are mentally retarded, but with a sweet and friendly personality. They are also typically short, and with congenital supravalvar aortic stenosis. Hypercalcemia may be present. First described by Williams in 1961.

Elfin face: An unusually flat face, with broad forehead, hypertelorism, short and upturned nose, low-set ears that are posteriorly rotated, puffy cheeks, wide mouth, patulous lips, hypoplastic teeth, and a deep husky voice. Patients are mentally retarded, but with a sweet and friendly personality. They are also typically short, and with congenital supravalvar aortic stenosis. Hypercalcemia may be present. First described by Williams in 1961.

Cherubic face: The child-like face of cherubism, a familial fibrous dysplasia of the jaws, with enlargement in childhood and regression in adulthood. Also seen in forms of glycogenosis.

Cherubic face: The child-like face of cherubism, a familial fibrous dysplasia of the jaws, with enlargement in childhood and regression in adulthood. Also seen in forms of glycogenosis.

Hound-dog face: The face of cutis laxa (dermatochalasis), a degenerative disease of elastic fibers, with skin progressively loose and hanging in folds—like that of a hound dog. Premature aging is common, and so are vascular abnormalities, gastrointestinal/bladder diverticula, and pulmonary emphysema. The face has an antimongoloid slant, slightly everted nostrils, prominent ears, and epicanthic folds. In contrast to Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, there is no joint laxity.

Hound-dog face: The face of cutis laxa (dermatochalasis), a degenerative disease of elastic fibers, with skin progressively loose and hanging in folds—like that of a hound dog. Premature aging is common, and so are vascular abnormalities, gastrointestinal/bladder diverticula, and pulmonary emphysema. The face has an antimongoloid slant, slightly everted nostrils, prominent ears, and epicanthic folds. In contrast to Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, there is no joint laxity.

Hurloid face: The coarse and gargoyle-like face of Hurler’s syndrome (mucopolysaccharidosis type I, described in 1919 by the German pediatrician Gertrud Hurler). Because of lack of L-iduronidase, these patients accumulate intracellular deposits, with abnormal skeletal cartilage and bone, dwarfism, kyphosis, deformed limbs, limited joint motion, spade-like hands, corneal clouding, hepatosplenomegaly, mental retardation, and, of course, a gargoyle-like face.

Hurloid face: The coarse and gargoyle-like face of Hurler’s syndrome (mucopolysaccharidosis type I, described in 1919 by the German pediatrician Gertrud Hurler). Because of lack of L-iduronidase, these patients accumulate intracellular deposits, with abnormal skeletal cartilage and bone, dwarfism, kyphosis, deformed limbs, limited joint motion, spade-like hands, corneal clouding, hepatosplenomegaly, mental retardation, and, of course, a gargoyle-like face.

Morquio’s face: The bizarre face of Morquio syndrome (mucopolysaccharidosis type IV). Like Hurler’s, this is also associated with short stature, but intelligence is normal. The face is coarse, with corneal clouding, large mouth, anteverted nose, and short neck. In addition, there may be chest and limb deformities (short and kyphotic trunk, pectus carinatum, protruded abdomen, and genu valgum), hepatosplenomegaly, urinary excretion of mucopolysaccharides, and neutrophils with intracytoplasmic metachromatic granules (Alder-Reilly bodies). Severe spinal defects may eventually lead to fatal cord compression and respiratory failure.

Morquio’s face: The bizarre face of Morquio syndrome (mucopolysaccharidosis type IV). Like Hurler’s, this is also associated with short stature, but intelligence is normal. The face is coarse, with corneal clouding, large mouth, anteverted nose, and short neck. In addition, there may be chest and limb deformities (short and kyphotic trunk, pectus carinatum, protruded abdomen, and genu valgum), hepatosplenomegaly, urinary excretion of mucopolysaccharides, and neutrophils with intracytoplasmic metachromatic granules (Alder-Reilly bodies). Severe spinal defects may eventually lead to fatal cord compression and respiratory failure.

Potter’s face: The characteristic facies of bilateral renal agenesis (Potter’s syndrome) and other kidney malformations: hypertelorism, prominent epicanthal folds, low-set ears, receding chin, and flattened nose. There may also be pulmonary hypoplasia and cardiac malformations (ventricular septal defect, endocardial cushion defect, tetralogy of Fallot, and patent ductus arteriosus).

Potter’s face: The characteristic facies of bilateral renal agenesis (Potter’s syndrome) and other kidney malformations: hypertelorism, prominent epicanthal folds, low-set ears, receding chin, and flattened nose. There may also be pulmonary hypoplasia and cardiac malformations (ventricular septal defect, endocardial cushion defect, tetralogy of Fallot, and patent ductus arteriosus).

Facies leonina: Also referred to as leontiasis, from the lion-like appearance. It is the face of advanced lepromatous leprosy, with prominent ridges and furrows of forehead and cheeks.

Facies leonina: Also referred to as leontiasis, from the lion-like appearance. It is the face of advanced lepromatous leprosy, with prominent ridges and furrows of forehead and cheeks.

Facies antonina: Another face of leprosy, with alterations in the eyelids and the anterior eye.

Facies antonina: Another face of leprosy, with alterations in the eyelids and the anterior eye.

Scaphoid face: From the Greek scaphos (boat-shaped, hollowed), this is the dish-like facial malformation of leprosy: protuberant forehead, prominent chin, depressed nose and maxilla.

Scaphoid face: From the Greek scaphos (boat-shaped, hollowed), this is the dish-like facial malformation of leprosy: protuberant forehead, prominent chin, depressed nose and maxilla.

Tetanus face: The risus sardonicus of tetanus (sardonic grin in Latin): open mouth with transversally tightened lips, resembling the smirk of Batman’s menace—the Joker.

Tetanus face: The risus sardonicus of tetanus (sardonic grin in Latin): open mouth with transversally tightened lips, resembling the smirk of Batman’s menace—the Joker.

Renal face: The face of chronic renal failure. Very similar to that of myxedema, except that the swelling is not due to accumulation of connective tissue but of water (hypoproteinemia).

Renal face: The face of chronic renal failure. Very similar to that of myxedema, except that the swelling is not due to accumulation of connective tissue but of water (hypoproteinemia).

Myxedematous face: Puffy and sallow facies from carotene accumulation, with coarse hair, boggy eyes, and dry, rough skin. The lateral third of the eyebrows is often missing.

Myxedematous face: Puffy and sallow facies from carotene accumulation, with coarse hair, boggy eyes, and dry, rough skin. The lateral third of the eyebrows is often missing.

Graves’ face: A typical and anxious-looking face, with exophthalmos and lid lag.

Graves’ face: A typical and anxious-looking face, with exophthalmos and lid lag.

Acromegalic face: Coarse facial features, thick bones, prominent mandible, protruding supraciliary areas, large nose and lips. From the Greek akron (extremity) and megalos (large), it is characterized by enlargement of the body’s peripheral parts: head, face, hands, and feet.

Acromegalic face: Coarse facial features, thick bones, prominent mandible, protruding supraciliary areas, large nose and lips. From the Greek akron (extremity) and megalos (large), it is characterized by enlargement of the body’s peripheral parts: head, face, hands, and feet.

Cushing’s face: A typical moon face: round, plethoric, oily, and ruddy. Acne, alopecia, and an increase in facial hair may also occur, as well as buffalo hump, buccal fat pads, striae, and central obesity.

Cushing’s face: A typical moon face: round, plethoric, oily, and ruddy. Acne, alopecia, and an increase in facial hair may also occur, as well as buffalo hump, buccal fat pads, striae, and central obesity.

Scleroderma face: The facies of progressive systemic sclerosis—sharp nose and skin so tightly drawn that wrinkles disappear. Most patients also have hyperpigmentation, with patches of vitiligo and a few telangiectasias. Mouth opening is often quite narrow.

Scleroderma face: The facies of progressive systemic sclerosis—sharp nose and skin so tightly drawn that wrinkles disappear. Most patients also have hyperpigmentation, with patches of vitiligo and a few telangiectasias. Mouth opening is often quite narrow.

Facies of lupus erythematosus: Malar and butterfly-like rash across the bridge of the nose.

Facies of lupus erythematosus: Malar and butterfly-like rash across the bridge of the nose.

Aortic face: The pale and sallow face of early aortic regurgitation (AR).

Aortic face: The pale and sallow face of early aortic regurgitation (AR).

Corvisart’s face: The characteristic facies of advanced AR or full-blown congestive heart failure—puffy, cyanotic, with swollen eyelids, and shiny eyes. First described by Jean Nicolas Corvisart, physician to Napoleon, Laënnec’s teacher, and percussion zealot.

Corvisart’s face: The characteristic facies of advanced AR or full-blown congestive heart failure—puffy, cyanotic, with swollen eyelids, and shiny eyes. First described by Jean Nicolas Corvisart, physician to Napoleon, Laënnec’s teacher, and percussion zealot.

De Musset’s face (or sign): Bobbing motion of the head, synchronous with each heartbeat, and “diagnostic” of AR. First described in the French poet Alfred De Musset, it is neither sensitive nor specific, since it can also occur in patients with very large stroke volume (i.e., hyperkinetic heart syndrome) and even a massive left pleural effusion. A variant of De Musset’s can occur in tricuspid regurgitation, even though in this case the systolic bobbing tends to be more lateral because of regurgitation along the superior vena cava.

De Musset’s face (or sign): Bobbing motion of the head, synchronous with each heartbeat, and “diagnostic” of AR. First described in the French poet Alfred De Musset, it is neither sensitive nor specific, since it can also occur in patients with very large stroke volume (i.e., hyperkinetic heart syndrome) and even a massive left pleural effusion. A variant of De Musset’s can occur in tricuspid regurgitation, even though in this case the systolic bobbing tends to be more lateral because of regurgitation along the superior vena cava.

Mitral face: The acrocyanotic face of mitral stenosis (MS). Due to peripheral desaturation from low and fixed cardiac output, it typically affects the distal parts of the body (akros, distal in Greek): nose tip, earlobes, cheeks, hands, and feet. When MS evolves into right-sided heart failure and tricuspid regurgitation (from longstanding pulmonary hypertension), the skin turns sallow and often overtly icteric. This contrasts markedly with the cyanotic hue of the cheeks.

Mitral face: The acrocyanotic face of mitral stenosis (MS). Due to peripheral desaturation from low and fixed cardiac output, it typically affects the distal parts of the body (akros, distal in Greek): nose tip, earlobes, cheeks, hands, and feet. When MS evolves into right-sided heart failure and tricuspid regurgitation (from longstanding pulmonary hypertension), the skin turns sallow and often overtly icteric. This contrasts markedly with the cyanotic hue of the cheeks.

Parkinson’s face: The mask-like facies of Parkinson’s. It has a fixed and apathetic look.

Parkinson’s face: The mask-like facies of Parkinson’s. It has a fixed and apathetic look.

Steinert’s face: The expressionless facies of myotonic dystrophy (Steinert’s disease)—frontal balding, cataracts, bilateral temporal muscle wasting, thin and beak-like nose, and tenting of the upper lip with tendency of the mouth to hang over.

Steinert’s face: The expressionless facies of myotonic dystrophy (Steinert’s disease)—frontal balding, cataracts, bilateral temporal muscle wasting, thin and beak-like nose, and tenting of the upper lip with tendency of the mouth to hang over.

Myasthenic face: The facies of myasthenia gravis, with sagging mouth corners and drooping eyelids (ptosis). Weak facial muscles result in paucity of expression (apathetic look).

Myasthenic face: The facies of myasthenia gravis, with sagging mouth corners and drooping eyelids (ptosis). Weak facial muscles result in paucity of expression (apathetic look).

Myopathic face: Seen in congenital myopathies. Similar to the myasthenic face—protruding lips, drooping eyelids, ophthalmoplegia, and a relaxation of facial muscles (Hutchinson’s face).

Myopathic face: Seen in congenital myopathies. Similar to the myasthenic face—protruding lips, drooping eyelids, ophthalmoplegia, and a relaxation of facial muscles (Hutchinson’s face).

Battle’s sign: The classic traumatic bruise over/behind the mastoid process. Due to basilar skull fracture with bleeding into the middle fossa. Can present at times as blood behind the eardrum. Battle’s sign may occur on the ipsilateral or contralateral side of the skull fracture and can take as long as 3–12 days to appear. It has low sensitivity (2–8%) but 100% predictive value.

Battle’s sign: The classic traumatic bruise over/behind the mastoid process. Due to basilar skull fracture with bleeding into the middle fossa. Can present at times as blood behind the eardrum. Battle’s sign may occur on the ipsilateral or contralateral side of the skull fracture and can take as long as 3–12 days to appear. It has low sensitivity (2–8%) but 100% predictive value.

Raccoon eyes: Periorbital bruises from external trauma to the eyes, skull fracture, and intracranial bleeding. Raccoon eyes may also occur in amyloidosis as a result of capillary fragility. In this case, the leak is often precipitated by a Valsalva-mediated increase in central venous pressure. This can be involuntary, as the one induced by proctoscopy.

Raccoon eyes: Periorbital bruises from external trauma to the eyes, skull fracture, and intracranial bleeding. Raccoon eyes may also occur in amyloidosis as a result of capillary fragility. In this case, the leak is often precipitated by a Valsalva-mediated increase in central venous pressure. This can be involuntary, as the one induced by proctoscopy.

Hippocratic face: A tense and dramatic expression, with sunken eyes, sharp nose, hollow cheeks, fallen-in temples, open mouth, dry and cracked lips, cold and drawn ears, and a leaden complexion. First described by Hippocrates in protracted and terminal illnesses.

Hippocratic face: A tense and dramatic expression, with sunken eyes, sharp nose, hollow cheeks, fallen-in temples, open mouth, dry and cracked lips, cold and drawn ears, and a leaden complexion. First described by Hippocrates in protracted and terminal illnesses.

Facies adenoid: The long, open-mouthed, and dumb-looking face of children with adenoidal hypertrophy. The mouth is open (because upper airway congestion renders them obligatory mouth-breathers); the nares are narrow, and the nose is pinched. Although typically adenoidal, this facies can also occur in recurrent upper respiratory tract allergies. Features include (1) Dennie’s lines (horizontal creases under both lower lids, named after the American Charles Dennie); (2) nasal pleat (the horizontal crease above the tip of the nose, due to the recurrent upward wiping of nasal secretions by either palm or dorsum of hand—“the allergic salute”); and (3) allergic shiners (bilateral infraorbital shadows due to chronic venous congestion).

Facies adenoid: The long, open-mouthed, and dumb-looking face of children with adenoidal hypertrophy. The mouth is open (because upper airway congestion renders them obligatory mouth-breathers); the nares are narrow, and the nose is pinched. Although typically adenoidal, this facies can also occur in recurrent upper respiratory tract allergies. Features include (1) Dennie’s lines (horizontal creases under both lower lids, named after the American Charles Dennie); (2) nasal pleat (the horizontal crease above the tip of the nose, due to the recurrent upward wiping of nasal secretions by either palm or dorsum of hand—“the allergic salute”); and (3) allergic shiners (bilateral infraorbital shadows due to chronic venous congestion).

Rhinophyma: A typical facial feature, immortalized by Ghirlandaio in his 1480 Louvre painting of an old man with grandson and then involuntarily popularized by W.C. Fields’ potato nose.

Rhinophyma: A typical facial feature, immortalized by Ghirlandaio in his 1480 Louvre painting of an old man with grandson and then involuntarily popularized by W.C. Fields’ potato nose.

Saddle nose: The congenital (or acquired) erosive indentation of the nasal bone and cartilage. Due to congenital syphilis, Wegener’s granulomatosis, and relapsing polychondritis.

Saddle nose: The congenital (or acquired) erosive indentation of the nasal bone and cartilage. Due to congenital syphilis, Wegener’s granulomatosis, and relapsing polychondritis.

Smoker’s face: A facies that is becoming increasingly familiar as a result of the tobacco epidemic. It is characterized by coarse features and a wrinkled, grayish, and atrophic skin that makes smokers look older. In fact, comparing smokers to nonsmokers may provide a much more effective prevention for teens (especially girls) than quoting the latest cancer statistics.

Smoker’s face: A facies that is becoming increasingly familiar as a result of the tobacco epidemic. It is characterized by coarse features and a wrinkled, grayish, and atrophic skin that makes smokers look older. In fact, comparing smokers to nonsmokers may provide a much more effective prevention for teens (especially girls) than quoting the latest cancer statistics.

Table 1-2 Disease Processes Associated with a Typical Facies

| Etiology | Facies | Disease |

|---|---|---|

| Congenital | Facies bovina | Greig’s syndrome |

| Elfin face | Williams’ syndrome | |

| Cherubic face | Cherubism | |

| Hound-dog face | Cutis laxa | |

| Hurloid face | Hurler’s syndrome | |

| Morquio’s face | Morquio’s syndrome | |

| Potter’s face | Potter’s syndrome | |

| Infectious | Facies leonina | Leprosy |

| Facies antonina | Leprosy | |

| Scaphoid face | Leprosy | |

| Tetanus face | Tetanus | |

| Endocrine-metabolic | Renal face | Chronic renal failure |

| Myxedematous face | Myxedema | |

| Graves’ face | Graves’ disease | |

| Acromegalic face | Acromegaly | |

| Cushing’s face | Cushing’s syndrome | |

| Rheumatologic | Scleroderma face | Progressive systemic sclerosis |

| Lupus face | Systemic lupus erythematosus | |

| Cardiovascular | Aortic face | Aortic regurgitation |

| Corvisart’s face | Aortic regurgitation | |

| De Musset’s face | Aortic regurgitation | |

| Mitral face | Mitral stenosis | |

| Neurologic | Parkinson’s face | Parkinson’s disease |

| Steinert’s face | Myotonic dystrophy | |

| Myasthenic face | Myasthenia gravis | |

| Myopathic face | Various | |

| Traumatic | Battle’s sign | Basilar skull fracture |

| Raccoon eyes | ||

| Miscellaneous | Hippocratic face | Terminal illness |

| Facies adenoid | Adenoids/chronic allergic rhinitis | |

| Rhinophyma | Various | |

| Saddle nose | Congenital syphilis/Wegener’s/polychondritis | |

| Smoker’s face | Tobacco |

E. Apparent Age

57 Which conditions make you look younger than your stated age?

Hypogonadism and other endocrine disorders of developmental arrest or retardation

Hypogonadism and other endocrine disorders of developmental arrest or retardation

Panhypopituitarism is also associated with a youthful look, but a sallow complexion and many fine wrinkles.

Panhypopituitarism is also associated with a youthful look, but a sallow complexion and many fine wrinkles.

Anorexia nervosa and some mental illnesses

Anorexia nervosa and some mental illnesses

Immunosuppressive agents for organ-transplant protection can do it, too.

Immunosuppressive agents for organ-transplant protection can do it, too.

Being mildly underweight also conveys an impression of youth and health, but this is probably more cultural and based on our ever-increasing obsession with thinness. In fact, when “consumption” from TB was still a major killer, being overweight was actually considered a sign of health. This is still the case in many parts of the world, where people’s main concern is not to lose weight, but to put food on the table at least once a day.

Being mildly underweight also conveys an impression of youth and health, but this is probably more cultural and based on our ever-increasing obsession with thinness. In fact, when “consumption” from TB was still a major killer, being overweight was actually considered a sign of health. This is still the case in many parts of the world, where people’s main concern is not to lose weight, but to put food on the table at least once a day.

F. Gait

65 How are stance and gait coordinated?

Basal ganglia: For automatic movements, including the automatic swinging of the arms

Basal ganglia: For automatic movements, including the automatic swinging of the arms

Locomotor region of the midbrain: For initiating walking

Locomotor region of the midbrain: For initiating walking

Cerebellum: For maintaining proper posture and balance; also controls the major characteristics of movement, such as trajectory, velocity, and acceleration.

Cerebellum: For maintaining proper posture and balance; also controls the major characteristics of movement, such as trajectory, velocity, and acceleration.

Spinal cord: For coordinating movements and relaying proprioceptive/sensory input from joints and muscles to the higher centers for feedback and autoregulation. Muscular tone must be high enough to resist gravity but low enough to allow movement.

Spinal cord: For coordinating movements and relaying proprioceptive/sensory input from joints and muscles to the higher centers for feedback and autoregulation. Muscular tone must be high enough to resist gravity but low enough to allow movement.

Vision: For feedback on head and body movement in relation to the surroundings, which allows for automatic balance adjustments whenever surface conditions change. Vision is crucial in case of reduced input from other sensory systems (e.g., proprioceptive, vestibular, and auditory).

Vision: For feedback on head and body movement in relation to the surroundings, which allows for automatic balance adjustments whenever surface conditions change. Vision is crucial in case of reduced input from other sensory systems (e.g., proprioceptive, vestibular, and auditory).

66 What are the two physiologic requirements of walking?

68 What are the four most common reasons for gait disturbance?

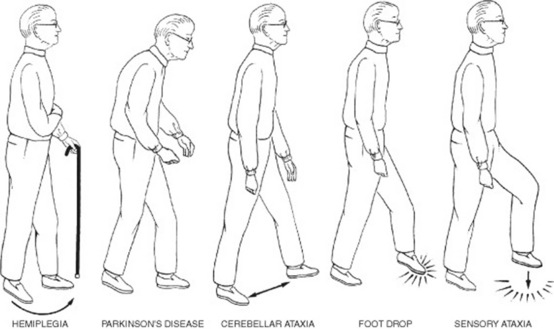

To separate them, always notice whether the disturbance is symmetric (suggesting faulty neurologic control, except for the spasticity of hemiplegia) or asymmetric (suggesting instead pain, a fixed joint, or muscle weakness) (Fig. 1-2 and Table 1-3).

| Mechanism | Gait Disturbance | Disease |

|---|---|---|

| Pain | Antalgic gait | Osteoarthritis hip, knee, ankle |

| Immobile joint | Fixed joint gait | Osteoarthritis; prolonged periods of plaster immobilization |

| Muscle weakness | Trendelenburg gait | Unilateral weakness of hip abductors |

| Anserine gait | Bilateral weakness of hip abductors | |

| High steppage gait | Weakness of hip abductors | |

| Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease | ||

| Foot drop (peroneal paralysis) | ||

| Abnormal neurologic control | Gait of spinal stenosis | Myelopathy (cervical spondylosis) |

| Gait of spastic paraplegia | Scissor gait | |

| Ataxic gait/cerebellar gait | Ataxia (sensory or cerebellar) | |

| Apraxic gait | Apraxia (frontal lobe disease) | |

| Hemiplegic gait | Hemispheric stroke | |

| Parkinsonian gait | Parkinson’s disease |

69 What historic information should be gathered to adequately evaluate an abnormal gait?

In addition to symmetry versus asymmetry (previously discussed), one should inquire about:

Acute onset (usually suggesting vascular disease versus drugs: alcohol, benzodiazepines, neuroleptics, and agents causing orthostatic hypotension)

Acute onset (usually suggesting vascular disease versus drugs: alcohol, benzodiazepines, neuroleptics, and agents causing orthostatic hypotension)

Presence of stiffness in the limbs

Presence of stiffness in the limbs

Difficulty in initiating or terminating walking

Difficulty in initiating or terminating walking

Presence of bladder or bowel dysfunction

Presence of bladder or bowel dysfunction

Association with vertigo or light-headedness

Association with vertigo or light-headedness

71 How should one observe a patient with a gait abnormality?

By closely evaluating (from front, back, and side):

How the patient gets up from a chair (useful in Parkinson’s or limb girdle dystrophy)

How the patient gets up from a chair (useful in Parkinson’s or limb girdle dystrophy)

How the patient initiates walking (also useful in Parkinson’s)

How the patient initiates walking (also useful in Parkinson’s)

How the patient walks at a slow pace

How the patient walks at a slow pace

How the patient walks at a fast pace

How the patient walks at a fast pace

How the patient walks on toes (this cannot be mustered by patients with Parkinson’s disease, sensory ataxia, spastic hemiplegia, or paresis of the soleus/gastrocnemius)

How the patient walks on toes (this cannot be mustered by patients with Parkinson’s disease, sensory ataxia, spastic hemiplegia, or paresis of the soleus/gastrocnemius)

How the patient walks on heels (diagnostic in motor ataxia, spastic paraplegia, or foot drop)

How the patient walks on heels (diagnostic in motor ataxia, spastic paraplegia, or foot drop)

How the patient walks a straight line in tandem (i.e., heel to toe) (useful in all gait disorders)

How the patient walks a straight line in tandem (i.e., heel to toe) (useful in all gait disorders)

How the patient walks with eyes first opened and then closed (a patient with sensory ataxia does much worse with closed eyes, whereas a patient with motor ataxia or cerebellar ataxia does poorly either way)

How the patient walks with eyes first opened and then closed (a patient with sensory ataxia does much worse with closed eyes, whereas a patient with motor ataxia or cerebellar ataxia does poorly either way)

How the patient stands erect with eyes first open and then closed (Romberg’s)

How the patient stands erect with eyes first open and then closed (Romberg’s)

How the patient copes with sudden postural challenges, such as a modest pull from behind after adequate warning; inadequate postural reflexes (as often seen in nursing home residents) will cause a few steps of retropulsion, and even a tendency to fall backward.

How the patient copes with sudden postural challenges, such as a modest pull from behind after adequate warning; inadequate postural reflexes (as often seen in nursing home residents) will cause a few steps of retropulsion, and even a tendency to fall backward.

(1) Gait Disturbances Due to Pain

73 What is an antalgic gait?

Gonarthrosis is associated with knee stiffness and inability to flex or extend the leg during gait.

Gonarthrosis is associated with knee stiffness and inability to flex or extend the leg during gait.

Coxarthrosis causes instead a coxalgic gait, characterized by a limited range of hip extension and a “lateral (or adductor) lurch.” This is an excessive lateral shift of the patient’s upper body toward the affected side when standing on the painful limb, which effectively relocates the center of gravity, thus reducing the weight load.

Coxarthrosis causes instead a coxalgic gait, characterized by a limited range of hip extension and a “lateral (or adductor) lurch.” This is an excessive lateral shift of the patient’s upper body toward the affected side when standing on the painful limb, which effectively relocates the center of gravity, thus reducing the weight load.

Finally, if the pain originates in the foot, there will be an incomplete (and very gentle) contact with the ground.

Finally, if the pain originates in the foot, there will be an incomplete (and very gentle) contact with the ground.

(2) Gait Disturbances Due to Immobile Joints

(3) Gait Disturbances Due to Muscle Weakness

75 What is the most common gait abnormality due to muscle weakness?

The one resulting from weak hip abductors (gluteus medius and minimus).

80 Describe the gait of “foot drop.”

High steppage: This consists of knees raised unusually high to allow the drooping foot to clear the ground. And yet, since the toes of the lifted foot remain pointed downward, they may still scrape the floor, thus resulting in frequent stumbles and falls. A foot drop can often be diagnosed by simply looking at the patient’s shoes, since wears and tears will be typically asymmetric, especially affecting the toes.

High steppage: This consists of knees raised unusually high to allow the drooping foot to clear the ground. And yet, since the toes of the lifted foot remain pointed downward, they may still scrape the floor, thus resulting in frequent stumbles and falls. A foot drop can often be diagnosed by simply looking at the patient’s shoes, since wears and tears will be typically asymmetric, especially affecting the toes.

“Foot slap”: After the heel touches the ground, the forefoot is brought down suddenly and in a slapping manner. This creates a typical double loud sound of contact (first the heel and then the forefront).

“Foot slap”: After the heel touches the ground, the forefoot is brought down suddenly and in a slapping manner. This creates a typical double loud sound of contact (first the heel and then the forefront).

(4) Gait Disturbances Due to Abnormal Neurologic Control

88 Describe the gait of spastic paraplegia.

With hips adducted and internally rotated (so that thighs rub together), and legs slightly flexed at the hips and knees. Overall, patients appear to be crouching. Because of their excessive adduction, legs are unable to move straight forward. Instead, they swing across each other in a typical criss-cross motion at the knees (“scissor gait”). Since ankles are plantarflexed, patients walk on tiptoe, with feet scraping the floor (and soles becoming typically worn along the toes). To compensate for the stiff movement of the legs, patients may move the trunk from side to side. For an illustration of the gait of spastic paraplegia, go to http://web.macam98.ac.il/∼shayke/hebrew/ppt/adaptask/adaptation/walk.htm.

98 What is a Parkinsonian gait?

Festination (progressively shorter and accelerated steps after the walk has finally begun, from the Latin festino, accelerate)

Festination (progressively shorter and accelerated steps after the walk has finally begun, from the Latin festino, accelerate)

Propulsion (a tendency to fall forward, and the reason for festination)

Propulsion (a tendency to fall forward, and the reason for festination)

Retropulsion (a tendency to involuntarily walk backward)

Retropulsion (a tendency to involuntarily walk backward)

Rigidity, causing not only a forward stoop, but also small shuffling steps, with dragged feet that scrape the ground

Rigidity, causing not only a forward stoop, but also small shuffling steps, with dragged feet that scrape the ground

1 Baraff LJ, Schriger DL. Orthostatic vital signs: Variation with age, specificity, and sensitivity in detecting a 450-mL blood loss. Ann Emerg Med. 1992;10:99-103.

2 Bergenwald L, Freyschuss U, Sjostrand T. The mechanism of orthostatic and haemorrhage fainting. Scand Clin Lab Invest. 1977;37:209-216.

3 Detsky AS, Smalley PS, Chang J. The rational clinical examination. Is this patient malnourished? JAMA. 1994;271:54-58.

4 Eaton D, Bannister P, Mulley GP, Conolly MJ. Axillary sweating in clinical assessment of dehydration in ill elderly patients. BMJ. 1994;308:1271.

5 Ebert RV, Stead EA, Gibson JG. Response of normal subjects to acute blood loss. Arch Intern Med. 1941;68:578-590.

6 Eisner LS. Diagnosing Gait Disorders (videotape). Secaucus, NJ: Continuing Medical Education, 1987.

7 Green DM, Metheny D. The estimation of acute blood loss by the tilt test. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1947;84:1045-1050.

8 Gross CR, Lindquist RD, Woolley AC, et al. Clinical indicators of dehydration severity in elderly patients. J Emerg Med. 1992;10:267-274.

9 Janssen I, Katzmarzyk PT, Ross R. Body mass index, waist circumference, and health risk. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:2074-2079.

10 Knepp R, Claypool R, Leonardi D. Use of the tilt test in measuring acute blood loss. Ann Emerg Med. 1980;9:72-75.

11 McGee S, Abernathy WB3rd, Simel DL. Is this patient hypovolemic? JAMA. 1999;281:1022-1029.

12 McGee S. Evidence-Based Physical Diagnosis. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders, 2001.

13 Ralston LA, Cobb LA, Bruce RA. Acute circulatory effects of arterial bleeding as determined by indicator-dilution curves in normal human subjects. Am Heart J. 1961;61:770-776.

14 Sapira JD. The Art and Science of Bedside Diagnosis. Baltimore: Urban & Shwarzenberg, 1990.

15 Shenkin HA, Cheney RH, Govons SR, et al. On the diagnosis of hemorrhage in man. Am J Med Sci. 1944;208:421-436.

16 Skillman JJ, Olson JE, Lyons JH, et al. The hemodynamic effect of acute blood loss in normal man, with observations on the effect of the Valsalva maneuver and breath holding. Ann Surg. 1967;166:713-738.

17 Wahrenberg H, Hertel K, Leijonhufvud BM, et al. Use of waist circumference to predict insulin resistance: Retrospective study. BMJ. 2005;330:1363-1364.

18 Wallace J, Sharpey-Schafer EP. Blood changes following controlled haemorrhage in man. Lancet. 1941;241:393-395.

19 Warren JV, Brannon ES, Stead EAJr, et al. The effect of venesection and the pooling of blood in the extremities on the atrial pressure and cardiac output in normal subjects with observations on acute circulatory collapse in three instances. J Clin Invest. 1945;24:337-344.

20 Willis JL, Schneiderman H, Algranati PS. Physical Diagnosis. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins, 1994.

21 Witting MD, Wears RL, Li S. Defining the positive tilt test. Ann Emerg Med. 1994;23:1320-1323.