12 Gastrointestinal system

Symptoms of gastrointestinal disease

The common symptoms of GI and abdominal disease are listed in Box 12.1 and are discussed individually below.

Abdominal pain

Abdominal pain is a common symptom which often accompanies serious diagnoses but frequently has no definable cause. As with any pain, it is important to characterize its site, intensity, character, areas of radiation, duration and frequency, together with aggravating and relieving factors and associated features. The particular clinical problem of acute abdmominal pain is discussed on page 237-238. The particular characteristics of pain from certain frequent and important causes are given in Box 12.2. Pain that comes in waves is described as being colicky. These waves are more frequent in pain from the gut, but vary over a longer time period when pain is from the biliary or renal tract. Abdominal pain may be due to causes that are not specifically in the abdomen such as metabolic disorders (porphyria or lead poisoning) or depression.

Box 12.2 Particular characteristics of pain from frequent and important causes (the regions of the abdomen are shown in Fig. 12.5 – the loin is lateral and posterior to the lumbar area)

Peptic ulcer: epigastric, burning or gnawing, radiates through to back, meal related, wakes the patient, relieved by antacid

Peptic ulcer: epigastric, burning or gnawing, radiates through to back, meal related, wakes the patient, relieved by antacid

Gastric cancer: epigastric, severe, partly meal related, not relieved by antacid

Gastric cancer: epigastric, severe, partly meal related, not relieved by antacid

Pancreatic: high epigastric, severe, felt front-to-back, immediately after eating, relieved by sitting forward

Pancreatic: high epigastric, severe, felt front-to-back, immediately after eating, relieved by sitting forward

Midgut: periumbilical, colicky, some relation to meals

Midgut: periumbilical, colicky, some relation to meals

Lower gut: periumbilical or suprapubic, colicky, some relief from bowel action

Lower gut: periumbilical or suprapubic, colicky, some relief from bowel action

Biliary: right upper quadrant, severe, colicky (but over a long time period), radiates to right shoulder, accompanied by nausea

Biliary: right upper quadrant, severe, colicky (but over a long time period), radiates to right shoulder, accompanied by nausea

Renal colic: loin-to-groin, colicky, very severe, accompanied by nausea

Renal colic: loin-to-groin, colicky, very severe, accompanied by nausea

Functional: anywhere in the abdomen, colicky, accompanied by bloating, relieved by bowel action

Functional: anywhere in the abdomen, colicky, accompanied by bloating, relieved by bowel action

Nutritional assessment

A full examination will include most signs of general and nutrient-specific malnutrition. Some detail of the latter is given in Table 12.1. Body weight is a key part of general examination as is height. These two can be related together and to a standard range by calculating the body mass index (BMI or Quetelet index). This is defined by the body weight (in kilograms), divided by the height (in metres) squared. The World Health Organization (WHO) classification of this index is given in Table 12.2. In the UK, the range 20-25 is often regarded as desirable, but the lower level of 18.5 is more applicable internationally. Patients with an index of more than 30 should undergo weight loss. In malnourished children, retardation of height lags behind that of weight and the relation between weight and height should always be compared with age using appropriate charts.

Table 12.1 Principal symptoms and signs due to vitamin and mineral deficiencies

| Nutrients | Deficiency syndrome | Principal symptoms/signs |

|---|---|---|

| Vitamin A, retinol (carotenoids) | Night blindness, keratomalacia | |

| Vitamin B1, thiamine | Wernicke/Korsakoff, beriberi | Nystagmus, sixth cranial nerve palsy, ataxia, acidosis, dementia, paraesthesiae, neuropathy and cardiac failure |

| Vitamin B2, riboflavin | Ariboflavinosis | Angular stomatitis, glossitis, magenta tongue |

| Niacin, nicotinic acid | Pellagra | Dermatitis of sun-exposed areas, dementia, poor appetite, difficulty sleeping, confusion, sore mouth |

| Vitamin B6, pyridoxine | Poor appetite, lassitude, oxaluria | |

| Pantothenic acid | Nausea, abdominal pain, paraesthesiae, burning feet | |

| Biotin | Dermatitis, depression, lassitude, muscle pains, electrocardiogram abnormalities, blepharitis | |

| Folic acid | Macrocytic anaemia, thrombocytopenia and megaloblastic bone marrow | |

| Vitamin B12 | Subacute combined degeneration, macrocytic anaemia | |

| Vitamin C, ascorbic acid | Scurvy | Poor wound healing, fatigue, limb pain, shortness of breath, difficulty sleeping, gingivitis, perifollicular purpura, hyperkeratosis |

| Vitamin D, ergo-/cholecalciferol | Rickets/osteomalacia | Bone pain, proximal myopathy |

| Vitamin E, tocopherol | Haemolysis, posterior column signs, ataxia, muscle wasting, retinitis pigmentosa-like changes, night blindness | |

| Vitamin K, phylloquinone and other menaquinones | Bruising, purpura, nose and GI bleeds | |

| Trace elements | ||

| Iron | Koilonychia, smooth tongue, anaemia, oesophageal web | |

| Zinc | Acrodermatitis enteropathica | Peristomal/perinasal/perineal erythema, thin hair, diarrhoea, apathy, anorexia, growth failure, hypoglycaemia |

| Copper | Microcytic hypochromic anaemia, neutropenia, scurvy-like bone lesions, osteoporosis | |

| Chromium | Peripheral neuropathy, hyperglycaemia | |

| Selenium | Cardiomyopathy | |

| Iodine | Goitre | |

Table 12.2 World Health Organization classification of body weight

| Category | BMI/Quetelet index |

|---|---|

| Underweight | <18.5 |

| Healthy weight | 18.5-24.9 |

| Overweight | 25-29.9 |

| Moderately obese | 30-34.9 |

| Severely obese | 35-39.9 |

| Morbidly obese | >40 |

Physical examination of the GI tract and abdomen

General signs

Systemic features of GI disease may be evident on general examination. Peripheral signs of chronic liver disease are listed in Box 12.3. Of these, the most common and useful are spider naevi (Fig. 12.1) (the presence of up to five small ones can be normal) and palmar erythema (Fig. 12.2) (the blotchy appearance often being more important than the overall redness). Inflammatory bowel disease may give rise to clubbing of the hands, arthritis, uveitis and skin changes including erythema nodosum (tender raised red lumps on the extensor surface of the limbs) and the much rarer pyoderma gangrenosum. Anaemia accompanies many GI diseases, as does oedema, and lymphadenopathy can be secondary to GI malignancy.

Box 12.3 Peripheral stigmata (signs) of chronic liver disease

Skin, nails and hands

Spider naevi – small telangectatic superficial blood vessels with a central feeding vessel

Spider naevi – small telangectatic superficial blood vessels with a central feeding vessel

Leuconychia – expansion of the paler half-moon at the base of the nail

Leuconychia – expansion of the paler half-moon at the base of the nail

Palmar erythema – seen on the thenar and hypothenar eminence – often with blotchy appearance

Palmar erythema – seen on the thenar and hypothenar eminence – often with blotchy appearance

Dupytren’s contracture – can occur in the absence of liver disease

Dupytren’s contracture – can occur in the absence of liver disease

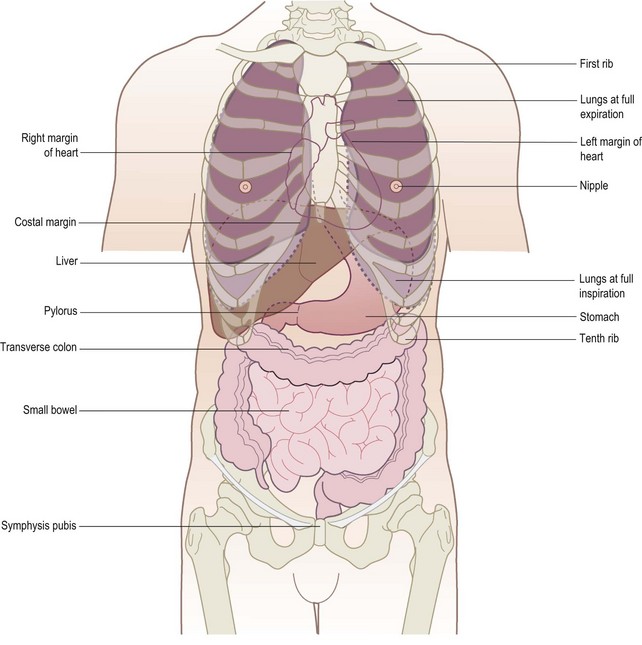

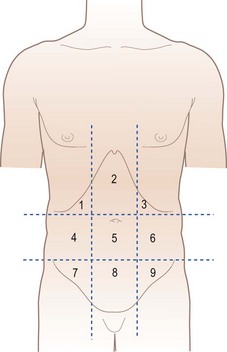

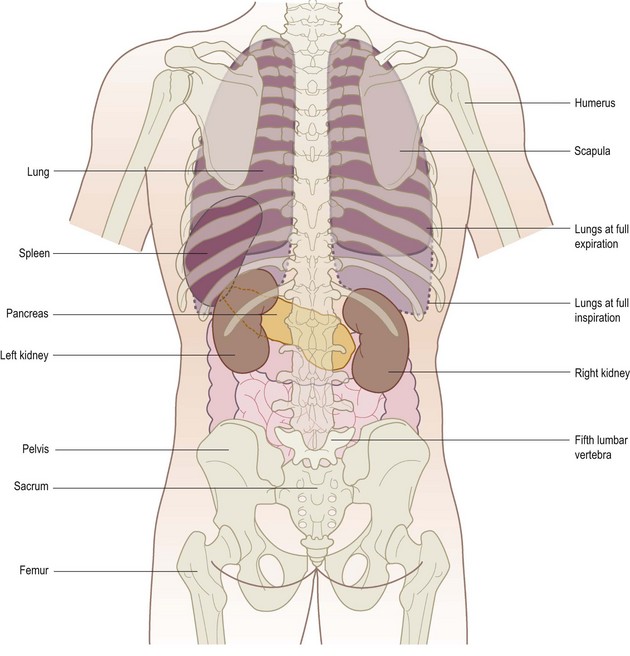

It is helpful when examining the patient, recording in notes or communicating information to colleagues to remember the surface anatomy of the structures related to the GI tract and abdomen (Figs 12.3 and 12.4) and to think of the abdomen as divided into regions (Fig. 12.5). The two lateral vertical planes pass from the femoral artery below to cross the costal margin close to the tip of the ninth costal cartilage. The two horizontal planes, the subcostal and interiliac, pass across the abdomen to connect the lowest points on the costal margin and the tubercles of the iliac crests, respectively.

Figure 12.4 Posterior view of the external relations of the abdominal and thoracic organs. The liver is not shown.

Inspection

The patient should be lying supine with arms loosely at the sides, the head and neck supported by up to two pillows, sufficient for comfort (Fig. 12.6). A sagging mattress makes examination difficult, particularly palpation. Make sure there is a good light, that the room is warm and that the hands are warm. A shivering patient cannot relax and vital signs, especially on palpation, may be missed.

Shape

Is the abdomen of normal contour and fullness, or distended? Is it scaphoid (sunken)?

Generalized fullness or distension may be due to fat, fluid, flatus, faeces or fetus.

Generalized fullness or distension may be due to fat, fluid, flatus, faeces or fetus.

Localized distension may be symmetrical and centred around the umbilicus as in the case of small bowel obstruction, or asymmetrical as in gross enlargement of the spleen, liver or ovary.

Localized distension may be symmetrical and centred around the umbilicus as in the case of small bowel obstruction, or asymmetrical as in gross enlargement of the spleen, liver or ovary.

Make a mental note of the site of any such swelling or distension; think of the anatomical structures in that region and note if there is any movement of the swelling, either with or independent of respiration.

Make a mental note of the site of any such swelling or distension; think of the anatomical structures in that region and note if there is any movement of the swelling, either with or independent of respiration.

Remember that chronic urinary retention may cause palpable enlargement in the lower abdomen.

Remember that chronic urinary retention may cause palpable enlargement in the lower abdomen.

A scaphoid abdomen is seen in advanced stages of starvation and malignant disease.

Movements of the abdominal wall

Visible peristalsis of the stomach or small intestine may be observed in three situations:

1 Obstruction at the pylorus. Visible peristalsis may occur where there is obstruction at the pylorus produced either by fibrosis following chronic duodenal ulceration or, less commonly, by carcinoma of the stomach in the pyloric antrum. In pyloric obstruction, a diffuse swelling may be seen in the left upper abdomen but, where obstruction is longstanding with severe gastric distension, this swelling may occupy the left mid and lower quadrants. Such a stomach may contain a large amount of fluid and, on shaking the abdomen, a splashing noise is usually heard (’succussion splash’). This splash is frequently heard in healthy patients for up to 3 hours after a meal, so enquire when the patient last ate or drank. In congenital pyloric stenosis of infancy, not only may visible peristalsis be apparent but also the grossly hypertrophied circular muscle of the antrum and pylorus may be felt as a ‘tumour’ to the right of the midline in the epigastrium. Both these signs may be elicited more easily after the infant has been given a feed. Standing behind the child’s mother with the child held on her lap may allow the child’s abdominal musculature to relax sufficiently to feel the walnut-sized swelling.

2 Obstruction in the distal small bowel. Peristalsis may be seen where there is intestinal obstruction in the distal small bowel or coexisting large and small bowel hold-up produced by distal colonic obstruction, with an incompetent ileocaecal valve allowing reflux of gas and liquid faeces into the ileum. Not only is the abdomen distended and tympanitic (hyper-resonant) but the distended coils of small bowel may be visible in a thin patient and tend to stand out in the centre of the abdomen in a ‘ladder pattern’.

3 As a normal finding in very thin, elderly patients with lax abdominal muscles or large, wide-necked incisional herniae seen through an abdominal scar.

Skin and surface of the abdomen

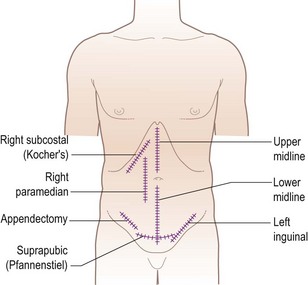

Note any scars present, their site, whether they are old (white) or recent (red or pink), linear or stretched (and therefore likely to be weak and contain an incisional hernia). Common examples are given in Fig. 12.7.

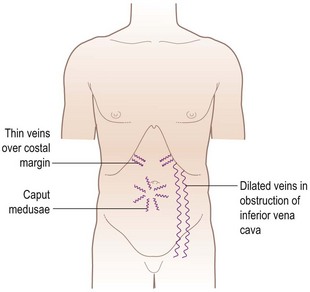

Look for prominent superficial veins, which may be apparent in three situations (Fig. 12.8): thin veins over the costal margin, usually of no significance; occlusion of the inferior vena cava; and venous anastomoses in portal hypertension. Inferior vena caval obstruction not only causes oedema of the limbs, buttocks and groins but, in time, distended veins on the abdominal wall and chest wall appear. These represent dilated anastomotic channels between the superficial epigastric and circumflex iliac veins below, and the lateral thoracic veins above, conveying the diverted blood from the long saphenous vein to the axillary vein; the direction of flow is therefore upwards. If the veins are prominent enough, try to detect the direction in which the blood is flowing by occluding a vein, emptying it by massage and then looking for the direction of refill. Distended veins around the umbilicus (caput medusae) are uncommon but signify portal hypertension, other signs of which may include splenomegaly and ascites. These distended veins represent the opening up of anastomoses between portal and systemic veins and occur in other sites, such as oesophageal and rectal varices.

Palpation

When palpating, the wrist and forearm should be in the same horizontal plane where possible, even if this means bending down or kneeling by the patient’s side. The best palpation technique involves moulding the relaxed right hand to the abdominal wall, not to hold it rigid (Fig. 12.9). The best movement is gentle but with firm pressure, with the fingers held almost straight but with slight flexion at the metacarpophalangeal joints and certainly avoiding sudden poking with the fingertips (Fig. 12.10).

Figure 12.9 Correct method of palpation. The hand is held flat and relaxed and ‘moulded’ to the abdominal wall.

Figure 12.10 Incorrect method of palpation. The hand is held rigid and mostly not in contact with the abdominal wall.

Palpation of intra-abdominal structures is an imperfect process in which the great sensitivity of the sense of touch and pressure is heavily masked by the abdominal wall tissue. It is unusual for structures to be very easily palpable and so it is necessary to concentrate fully on the task and to try and visualize the normal anatomical structures and what might be palpable beneath the examining hand. It may be necessary to repeat the palpation more slowly and deeply. Putting the left hand on top of the right allows increased pressure to be exerted (Fig. 12.11), such as with an obese or very muscular patient.

Start in the left lower quadrant of the abdomen, palpating lightly, and repeat for each quadrant.

Start in the left lower quadrant of the abdomen, palpating lightly, and repeat for each quadrant.

Repeat using slightly deeper palpation examining each of the nine areas of the abdomen.

Repeat using slightly deeper palpation examining each of the nine areas of the abdomen.

Feel for the aorta and para-aortic glands and common femoral vessels.

Feel for the aorta and para-aortic glands and common femoral vessels.

If a swelling is palpable, spend time eliciting its features.

If a swelling is palpable, spend time eliciting its features.

Left kidney

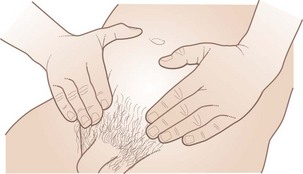

The right hand is placed anteriorly in the left lumbar region while the left hand is placed posteriorly in the left loin (Fig. 12.12). Ask the patient to take a deep breath in, press the left hand forward and the right hand backward, upward and inward. The left kidney is not usually palpable unless either low in position or enlarged. Its lower pole, when palpable, is felt as a rounded firm swelling between both right and left hands (i.e. bimanually palpable) and it can be pushed from one hand to the other, in an action which is called ‘ballotting’.

Spleen

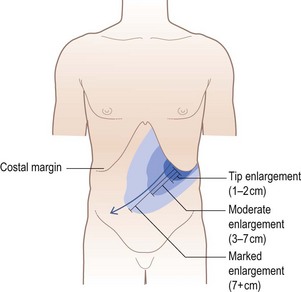

Like the left kidney, the spleen is not normally palpable. It has to be enlarged to two or three times its usual size before it becomes palpable, and then is felt beneath the left subcostal margin. Enlargement takes place in a superior and posterior direction before it becomes palpable subcostally. Once the spleen has become palpable, the direction of further enlargement is downwards and towards the right iliac fossa (Fig. 12.13). Place the flat of the left hand over the lower-most rib cage posterolaterally, thus restricting the expansion of the left lower ribs on inspiration and concentrating more of the inspiratory movement into moving the spleeen downwards. The right hand is placed beneath the costal margin well out to the left. Press in deeply with the fingers of the right hand beneath the costal margin, at the same time exerting considerable pressure medially and downwards with the left hand (Fig. 12.14), and then ask the patient to breathe in deeply. Repeat this manoeuvre with the right hand being moved more medially beneath the costal margin on each occasion (Fig. 12.15). If enlargement of the spleen is suspected from the history and it is still not palpable, turn the patient half on to the right side, ask him to relax back onto your left hand, which is now supporting the lower ribs, and repeat the examination as above. Alternatively the spleen may be very large and the lower edge may be much lower than at first suspected. It may help to ask the patient to place the left hand on your right shoulder while palpating for the spleen.

Right kidney

Feel for the right kidney in much the same way as for the left. Place the right hand horizontally in the right lumbar region anteriorly with the left hand placed posteriorly in the right loin. Push forwards with the left hand, press the right hand inward and upward (Fig. 12.16) and ask the patient to take a deep breath in. The lower pole of the right kidney, unlike the left, is commonly palpable in thin patients and is felt as a smooth, rounded swelling which descends on inspiration and is bimanually palpable and may be ‘ballotted’.

Liver

Sit on the couch beside the patient. Place both hands side-by-side flat on the abdomen in the right subcostal region lateral to the rectus with the fingers pointing towards the ribs. If resistance is encountered, move the hands further down until this resistance disappears. Exert gentle pressure and ask the patient to breathe in deeply. Concentrate on whether the edge of the liver can be felt moving downwards and under the examining hand (Fig. 12.17).

Repeat this manoeuvre working from lateral to medial regions to trace the liver edge as it passes upwards to cross from right hypochondrium to epigastrium. Another commonly employed though less accurate method of feeling for an enlarged liver is to place the right hand below and parallel to the right subcostal margin. The liver edge will then be felt against the radial border of the index finger (Fig. 12.18). The liver is often palpable in normal patients without being enlarged. The lower edge of the liver can be clarified by percussion (see below), as can the upper border in order to determine overall size: a palpable liver edge can be due to enlargement, or displacement downwards by lung pathology. Hepatomegaly conventionally is measured in centimetres palpable below the right costal margin, which should be determined with a ruler if possible.

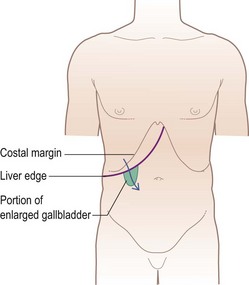

Gallbladder

The gallbladder is palpated in the same way as the liver. The normal gallbladder cannot be felt. When it is distended, however, it forms an important sign and may be palpated as a firm, smooth, or globular swelling with distinct borders, just lateral to the edge of the rectus abdominis near the tip of the ninth costal cartilage. It moves with respiration. Its upper border merges with the lower border of the right lobe of the liver, or disappears beneath the costal margin and therefore can never be felt (Fig. 12.19). When the liver is enlarged or the gallbladder grossly distended, the latter may be felt not in the hypochondrium, but in the right lumbar or even as low down as the right iliac region.

In a jaundiced patient with carcinoma of the head of the pancreas or other malignant causes of obstruction of the common bile duct (below the entry of the cystic duct), the ducts above the obstruction become dilated, as does the gallbladder (see Courvoisier’s law, below).

In a jaundiced patient with carcinoma of the head of the pancreas or other malignant causes of obstruction of the common bile duct (below the entry of the cystic duct), the ducts above the obstruction become dilated, as does the gallbladder (see Courvoisier’s law, below).

In mucocele of the gallbladder, a gallstone becomes impacted in the neck of a collapsed, empty, uninfected gallbladder and mucus continues to be secreted into its lumen (Fig. 12.20). Eventually, the uninfected gallbladder is so distended that it becomes palpable. In this case, the bile ducts are normal and the patient is not jaundiced.

In mucocele of the gallbladder, a gallstone becomes impacted in the neck of a collapsed, empty, uninfected gallbladder and mucus continues to be secreted into its lumen (Fig. 12.20). Eventually, the uninfected gallbladder is so distended that it becomes palpable. In this case, the bile ducts are normal and the patient is not jaundiced.

In carcinoma of the gallbladder, the gallbladder may be felt as a stony, hard, irregular swelling, unlike the firm, regular swelling of the two above-mentioned conditions.

In carcinoma of the gallbladder, the gallbladder may be felt as a stony, hard, irregular swelling, unlike the firm, regular swelling of the two above-mentioned conditions.

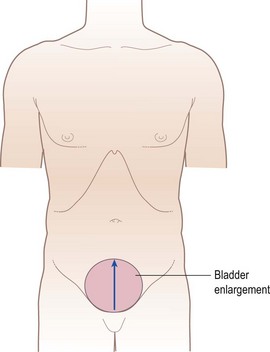

The urinary bladder

Normally the urinary bladder is not palpable. When it is full and the patient cannot empty it (retention of urine), a smooth firm regular oval-shaped swelling will be palpated in the suprapubic region and its dome (upper border) may reach as far as the umbilicus. The lateral and upper borders can be readily made out, but it is not possible to feel its lower border (i.e. the swelling is ‘arising out of the pelvis’). The fact that this swelling is symmetrically placed in the suprapubic region beneath the umbilicus, that it is dull to percussion and that pressure on it gives the patient a desire to micturate, together with the signs above, confirm such a swelling as the bladder (Fig. 12.21).

The aorta and common femoral vessels

In most adults, the aorta is not readily felt, but with practice it can usually be detected by deep palpation a little above and to the left of the umbilicus. In thin patients, particularly women with a marked lumbar lordosis, the aorta is more easily palpable. Palpation of the aorta is one of the few occasions in the abdomen when the fingertips are used as a means of palpation. Press the extended fingers of both hands, held side by side, deeply into the abdominal wall in the position shown in Fig. 12.22; make out the left wall of the aorta and note its pulsation. Remove both hands and repeat the manoeuvre a few centimetres to the right. In this way the pulsation and width of the aorta can be estimated. It is difficult to detect small aortic aneurysms; where a large one is present, its presence and width may be assessed by placing the extended fingertips on either side of it with the palms flat on the abdominal wall and the fingers pointing towards each other. When the fingertips are either side of an aneurysm, it should be clear that they are being separated by each pulsation and not just moved up and down (this latter manoeuvre can involve very deep palpation and the patient should be warned).

The common femoral vessels are found just below the inguinal ligament at the mid-point between the anterior superior iliac spine and symphysis pubis. Place the pulps of the right index, middle and ring fingers over this site in the right groin and palpate the wall of the vessel. Note the strength and character of its pulsation and then compare it with the opposite femoral pulse (Fig. 12.23).

What to do when an abdominal mass is palpable

Size and shape

As a general rule, gross enlargement of the liver, spleen, uterus, bladder or ovary presents no undue difficulty in diagnosis. On the other hand, swellings arising from the stomach, small or large bowel, retroperitoneal structures such as the pancreas, or the peritoneum (see section on mobility, below), may be difficult to diagnose. The larger a swelling arising from one of these structures, the more it tends to distort the outline of the organ of origin (e.g. a large renal mass can feel as if it is arising from intraperitoneal organs).

Mobility and attachments

When the swelling is completely fixed, it usually signifies one of three things:

1 A mass of retroperitoneal origin (e.g. pancreas).

2 Part of an advanced tumour with extensive spread to the anterior or posterior abdominal walls or abdominal organs.

3 A swelling resulting from severe chronic inflammation involving other organs (e.g. diverticulitis of the sigmoid colon or a tuberculous ileocaecal mass).

Percussion

Details of how to percuss correctly are given in Chapter 10. The normal percussion note over most of the abdomen is resonant (tympanic) except over the liver, where the note is dull. A normal spleen is not large enough to render the percussion note dull. A resonant percussion note over suspected enlargement of liver or spleen weighs against there being true enlargement.

Defining the boundaries of abdominal organs and masses

Spleen

Percussion over a substantially enlarged spleen provides rapid confirmation of the findings detected on palpation (see Fig. 12.14). Dullness extends from the left lower ribs into the left hypochondrium and left lumbar region.

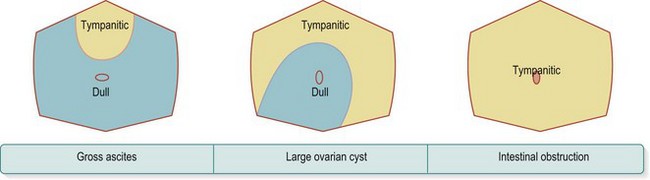

Detection of ascites and its differentiation from ovarian cyst and intestinal obstruction

There are three common causes of diffuse enlargement of the abdomen:

1 The presence of free fluid in the peritoneum (ascites).

3 Obstruction of the large bowel, distal small bowel or both.

Percussion rapidly distinguishes between these three, as can be seen in Figure 12.24. Other helpful symptoms or signs which are usually present are listed in Box 12.4.

To elicit a fluid thrill, the patient is again laid supine. Place one hand flat over the lumbar region of one side, and get an assistant to put the side of their hand longitudinally and firmly in the midline of the abdomen. Then flick or tap the opposite lumbar region (Fig. 12.25). A fluid thrill or wave is felt as a definite and unmistakable impulse by the detecting hand held flat in the lumbar region. (The purpose of the assistant’s hand is to dampen any impulse that may be transmitted through the fat of the abdominal wall.) As a rule, a fluid thrill is felt only when there is a large amount of ascites present which is under tension, and it is not a very reliable sign.

Auscultation

Auscultation of the abdomen is for detecting bowel sounds and vascular bruits.

The groins

Once the groins have been inspected, ask the patient to turn the head away from you and cough. Look at both inguinal canals for any expansile impulse. If none is apparent, place the left hand in the left groin so that the fingers lie over and in line with the inguinal canal; place the right hand similarly in the right groin (Fig. 12.26). Now ask the patient to give a loud cough and feel for any expansile impulse with each hand. When a patient coughs, the muscles of the abdominal wall contract violently and this imparts a definite, though not expansile, impulse to the palpating hands which is a source of confusion to the inexperienced. Trying to differentiate this normal contraction from a small, fully reducible inguinal hernia is difficult, and the matter can usually be resolved only when the patient is standing up.

The femoral vessels have already been felt (see Fig. 12.23) and auscultated. Now palpate along the femoral artery for enlarged inguinal nodes, feeling with the fingers of the right hand, and carry this palpation medially beneath the inguinal ligament towards the perineum. Then repeat this on the left side. A patient who complains of a lump in the groin should be examined lying down and standing up.

What to do if a patient complains of a lump in the groin

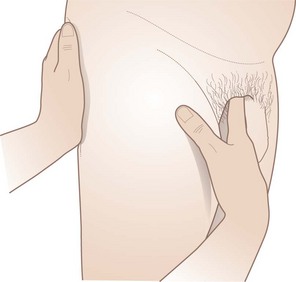

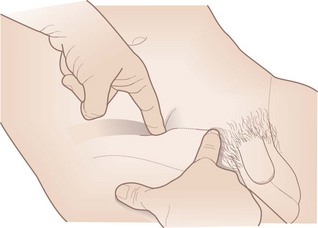

Next decide whether the hernia is inguinal or femoral. The best way to do this is to determine the relationship of the sac to the pubic tubercle. To locate this structure, push gently upwards from beneath the neck of the scrotum with the index finger (Fig. 12.27) but do not invaginate the neck of the scrotum as this is painful. The tubercle will be felt as a small bony prominence 2 cm from the midline on the pubic crest. In thin patients, the tubercle is easily felt but this is not so in the obese. If difficulty is found, follow up the tendon of adductor longus, which arises just below the tubercle.

If it has been decided that the hernia is inguinal, then one needs to know these further points:

What are the contents of the sac? Bowel tends to gurgle, is soft and compressible, while omentum feels firmer and is of a doughy consistency.

What are the contents of the sac? Bowel tends to gurgle, is soft and compressible, while omentum feels firmer and is of a doughy consistency.

Is the hernia fully reducible or not? It is best to lie the patient down to decide this. Ask the patient if he is “able to push the hernia back in” and, if so, ask him to do so and confirm yourself. (It is more painful if the examiner reduces it.)

Is the hernia fully reducible or not? It is best to lie the patient down to decide this. Ask the patient if he is “able to push the hernia back in” and, if so, ask him to do so and confirm yourself. (It is more painful if the examiner reduces it.)

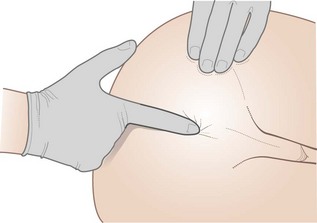

Is the hernia direct or indirect? Again, it is best to lie the patient down to decide this. Inspection of the direction of the impulse is often diagnostic, especially in thin patients. A direct hernia tends to bulge straight out through the posterior wall of the inguinal canal, while in an indirect hernia the impulse can often be seen to travel obliquely down the inguinal canal. Another helpful point is to place one finger just above the mid-inguinal point over the deep inguinal ring (Fig. 12.28). If a hernia is fully controlled by this finger, it must be an indirect inguinal hernia.

Is the hernia direct or indirect? Again, it is best to lie the patient down to decide this. Inspection of the direction of the impulse is often diagnostic, especially in thin patients. A direct hernia tends to bulge straight out through the posterior wall of the inguinal canal, while in an indirect hernia the impulse can often be seen to travel obliquely down the inguinal canal. Another helpful point is to place one finger just above the mid-inguinal point over the deep inguinal ring (Fig. 12.28). If a hernia is fully controlled by this finger, it must be an indirect inguinal hernia.

Figure 12.28 Left hand: index finger occluding the deep inguinal ring. Right hand: index finger on the pubic tubercle.

The examination is completed by following the same scheme in the opposite groin.

The male genitalia

The examination of the genitalia is important in men presenting with abnormalities in the groin, and in many acute or subacute abdominal syndromes. Thus, disease of the genitalia may lead to abdominal symptoms, such as pain or swelling. It is vital to give a careful and ongoing explanation of what is involved and why, throughout this part of the examination. A detailed description of the examination of the male genitalia is given in Chapter 21.

The female genitalia

These are described in Chapters 4 and 21. As in men, examination of the genitalia is an important part of overall examination, and it is vital to give a careful and ongoing explanation of what is involved and why, throughout this part of the examination.

The anus and rectum

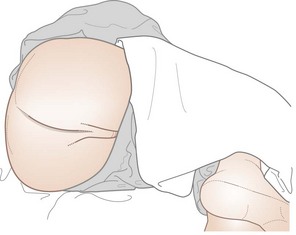

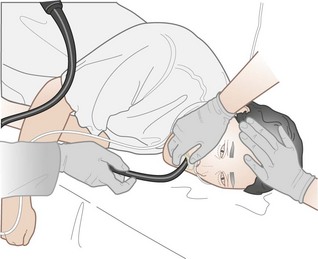

The left lateral position is best for routine examination of the rectum (Fig. 12.29). Make sure that the buttocks project over the side of the couch with the knees drawn well up, and that a good light is available. Put on disposable gloves and stand behind the patient’s back, facing the patient’s feet. Explain to the patient what you are about to do, that you will be as gentle as possible and that you will stop the examination, if requested, at any time.

Digitial rectal examination (palpation)

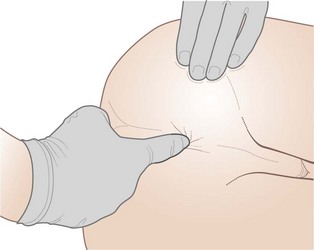

Put a generous amount of lubricant on the gloved index finger of the right hand, place the pulp of the finger (not the tip) flat on the anus (Figs 12.30 and 12.31) and press firmly and slowly (flexing the finger) in a slightly backwards direction. After initial resistance, the anal sphincter relaxes and the finger can be passed into the anal canal. If severe pain is elicited when attempting this manoeuvre, then further examination should be abandoned as it is likely the patient has a fissure and the rest of the examination will be very painful and unhelpful.

The acute abdomen

History

The patient usually presents with acute abdominal pain (which is also discussed in Chapter 8). As for any pain, its site, severity, radiation, character, time and circumstances of onset and any aggravating or relieving features are all important.

Examination of abdominal fluids

Examination of faeces

Aspiration of peritoneal fluid

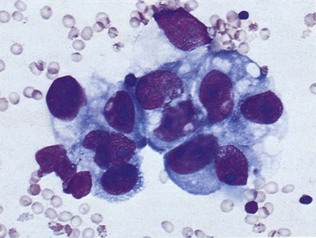

The fluid withdrawn is sent for bacteriological and cytological examination and chemical analysis. Transudates, such as occur in heart failure, cirrhosis and nephrotic syndrome, normally have a protein content under 25 g/l (i.e. less than two-thirds the concentration of albumin in the plasma). Exudates occurring in tuberculous peritonitis or in the presence of secondary malignancy usually contain more than 25 g/l of protein. This method of distinction, however, is somewhat unreliable. Lymphocytes in the fluid are characteristic features of tuberculous peritonitis but acid-fast bacilli are often not seen on staining. Blood-stained fluid strongly suggests a malignant cause, and malignant cells may also be demonstrated (Fig. 12.33).

Special techniques in the examination of the GI tract

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy

In the last 40 years or so, the developments of the fibreoptic endoscope, and more recently of video-endoscopy, have revolutionized the assessment of the upper-GI tract (Fig. 12.34). With these instruments it is possible to inspect directly as far as the duodenal loop, with or without light sedation and local pharyngeal anaesthesia. Because of the ability to photograph and biopsy any suspicious lesions, this technique is the investigation of choice for demonstrating structural abnormalities in the upper gut. Therapeutic endoscopy is now the treatment of choice for bleeding oesophageal varices, benign oesophageal obstruction and in many cases of bleeding peptic ulcer (Fig. 12.35). In inoperable cancer of the oesophagus, palliative prostheses (stents) can be inserted endoscopically.

Radiology of the upper gastrointestinal tract

Plain radiographs

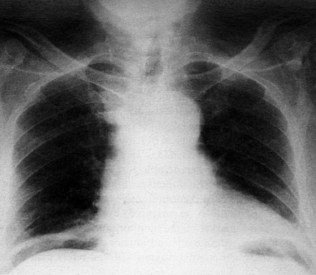

Plain radiographs of the chest and abdomen with the patient supine and in the erect position are of great value in cases of suspected peritonitis due to a perforated viscus, when gas may be seen under the diaphragm, usually on the right side (Fig. 12.36). A plain abdominal X-ray is useful in suspected intestinal obstruction or ileus when dilated bowel loops may be seen with fluid levels appearing on the erect X-ray.

Small intestine

Colon, rectum and anus

Rigid sigmoidoscopy and other tests in chronic diarrhoea

Urine tests for purgative abuse are useful in the investigation of persistent unexplained diarrhoea.

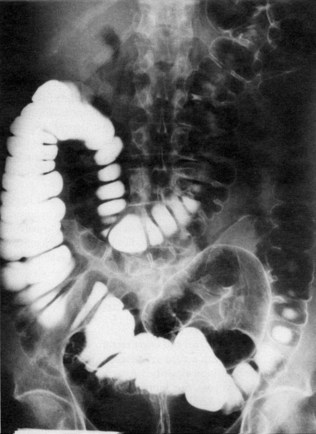

Barium enema

Prior to barium enema, the patient must have his bowel prepared with a vigorous laxative, as residual stool or fluid can be mistaken for polyps and other lesions. Impending obstruction is a contraindication to this laxative preparation. A plain X-ray of the abdomen should always be taken in patients with suspected perforation or obstruction before considering a contrast study (see Fig. 12.32).

Following evacuation, air is introduced into the colon. This improves visualization of the mucosa and is especially valuable for detecting small lesions such as polyps and early tumours (Figs 12.37 and 12.38).

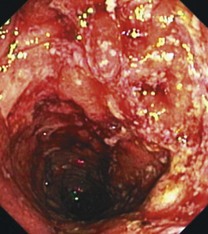

Colonoscopy and flexible sigmoidoscopy

As in the upper gut, the use of flexible fibreoptic and video instruments has revolutionized the investigation of the colon. Both sigmoidoscopes and colonoscopes are available. The former instrument may be employed in an outpatient setting after a simple enema preparation; the latter requires more extensive colon preparation (similar to barium enema X-ray) and sedation but is also an outpatient procedure. These techniques are invaluable for obtaining tissue for diagnosis of inflammatory and neoplastic disease and for removal of neoplastic polyps (Figs 12.39 and 12.40). Dilatation of strictures, stenting, laser or other thermal treatments of obstructing tumours can also be applied during endoscopy.

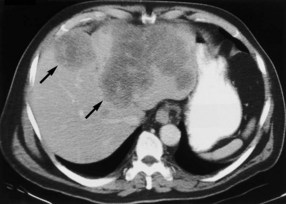

Computed tomography scanning

Computed tomography (CT) can be used to produce cross-sectional images of the liver and other intra-abdominal and retroperitoneal organs. It is particularly helpful in assessing patients with cancer of the oesophagus, stomach, pancreas and colon (Fig 12.41). Because it can be combined with injection of vascular contrast, it can be helpful in assessing intra-abdominal vascular abnormalities. It can facilitate guided biopsy of abnormalities, and drainage of fluid and other collections. It is also increasingly being used to image the bowel, particularly if there is suspected obstruction, and is widely used in assessing patients with an acute abdomen.