96 Gastrointestinal Infections

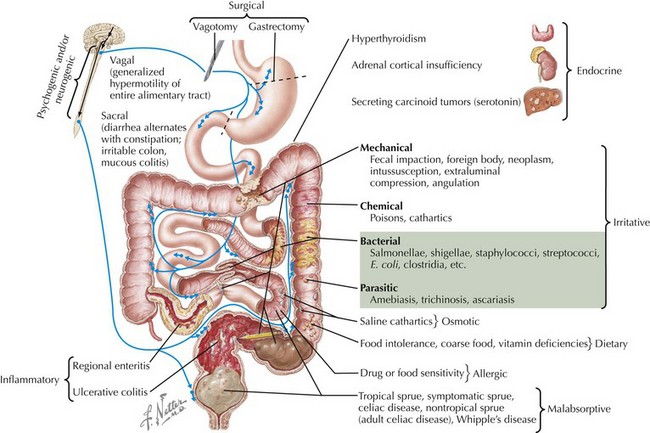

Gastrointestinal (GI) infections, particularly acute gastroenteritis, cause significant pediatric morbidity and mortality worldwide. Gastroenteritis is an infection of the GI tract characterized by vomiting, diarrhea, or both with three or more loose or watery stools a day. The worldwide mortality of diarrheal illness in children has been estimated at 1.8 million. In the United States, it is estimated that gastroenteritis primarily affects children younger than 5 years of age with 21 to 37 million episodes annually, approximately 200,000 hospitalizations, and 300 to 400 deaths per year. More readily accessible treatment has been made through the uptake of aggressive oral rehydration therapy (ORT). The causes of acute diarrhea in children differ by location, time of year, and immunologic status (Figure 96-1). This chapter discusses diarrheal illness caused by bacteria and viruses; parasites are discussed in Chapter 99. Additional infections of the GI tract are briefly addressed, including appendicitis, peritonitis, and intraabdominal abscesses.

Acute Infectious Diarrhea

Etiology and Pathophysiology

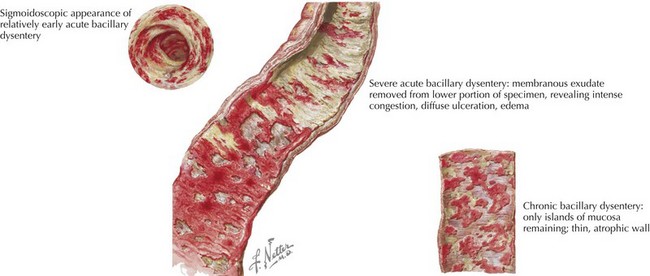

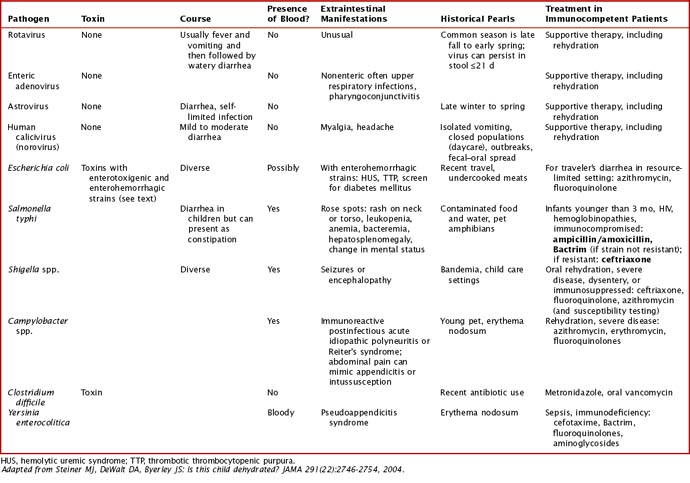

Common viral etiologies of acute infectious diarrhea in immunocompetent children include rotavirus, enteric adenoviruses, noroviruses, and astroviruses. Common bacterial pathogens include Salmonella spp., Escherichia coli, Shigella spp., and Campylobacter jejuni (Figure 96-2). Clostridium difficile is the most common cause of antibiotic-associated diarrhea, although its role in infants younger than 1 year of age is unclear. Additional causes are discussed in Table 96-1 with further discussion of treatment. These pathogens cause diarrhea by a variety of pathogenic means: (1) osmotic or malabsorptive, (3) inflammatory, and (3) toxigenic. In immunocompromised hosts, cytomegalovirus and herpes simplex virus should also be considered as causes of infectious diarrhea.

Clinical Presentation

Certain infectious agents are associated with extraintestinal manifestations. Shigella spp. organisms produce a toxin that has been associated with seizure. Yersinia enterocolitica infection has been associated with reactive arthritis. Additional extraintestinal manifestations can be seen in Table 96-1.

Evaluation and Management

A brief discussion of rehydration is provided here, but more detailed discussions can be found in the Suggested Readings section at the end of the chapter. Current recommendations from the American Academy of Pediatrics encourage use of ORT in managing acute gastroenteritis in children. Oral rehydration occurs in two phases of treatment: a rehydration phase in which water and electrolytes are given in the form of an oral rehydration solution (ORS) for existing losses and a maintenance phase. ORS introduces glucose as well as sodium at the same time to allow for coupled transport. The World Health Organization’s components for rehydration solution consist of at least a complex carbohydrate or 2% glucose and 50 to 90 m Eq/L of sodium. Early refeeding is now encouraged after previous losses are corrected. Antimicrobial therapies for certain bacterial etiologies are discussed in Table 96-1.

Appendicitis

Peritonitis and Intraabdominal Abscesses

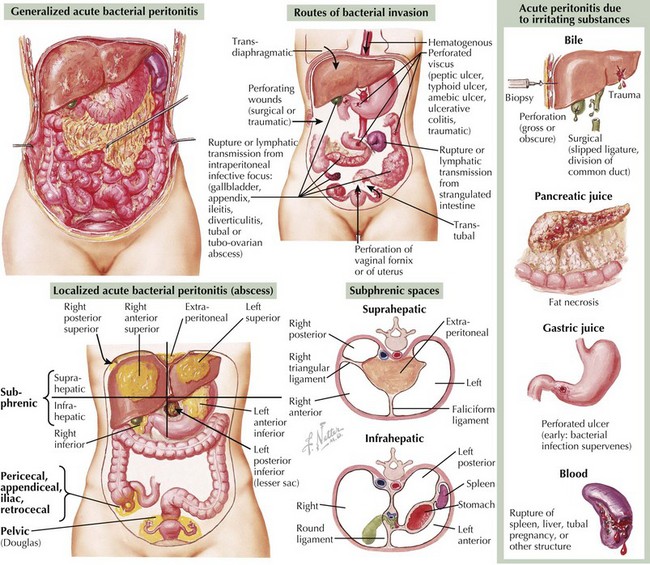

Peritonitis is the inflammation of the peritoneum, either from infectious or noninfectious etiologies. Additional causes of abdominal pain in children caused by infection include peritonitis and intraabdominal abscesses, which can present after acute appendicitis or gastroenteritis (Figure 96-3).

Etiology and Pathogenesis

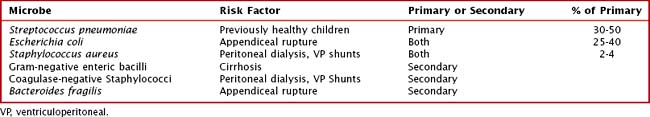

Peritonitis may lead to formation of a phlegmon and may then proceed to abscess formation. Additional abscesses in the abdomen may occur within organ structures, especially the liver and spleen, through bacteremia. Amebic abscesses in the liver are discussed in Chapter 99. The microbes involved in peritonitis and abscesses are listed in Table 96-2. The most common targets of therapy are E. coli and Bacteroides spp.

Bundy DG, Byerley JS, Liles EA, et al. Does this child have appendicitis? JAMA. 2007;298(4):438-451.

Goldin AB, Sawin RS, Garrison MM, et al. Aminoglycoside-based triple-antibiotic therapy versus monotherapy for children with ruptured appendicitis. Pediatrics. 2007;119(5):905-911.

Gorelick MH, Shaw KN, Murphy KO. Validity and reliability of clinical signs in the diagnosis of dehydration in children. Pediatrics. 1997;99:E6.

Hartling L, Bellemare S, Wiebe N, et al: Oral versus intravenous rehydration for treating dehydration due to gastroenteritis in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 3:CD004390, 2006.

Kharbanda AB, Taylor GA, Bachur RG. Suspected appendicitis in children: rectal and intravenous contrast-enhanced versus intravenous contrast-enhanced CT. Radiology. 2007;243:520-526.

Kim JY. Peritonitis and intra-abdominal abscess. In: Pediatric Infectious Diseases: The Requisites in Pediatrics. Philadelphia: Mosby Elsevier; 2008.

King CK, Glass R, Bresee JS, Duggan C, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Managing acute gastroenteritis among children: oral rehydration, maintenance, and nutritional therapy. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;21:52.

Pickering LK. Red Book: 2006 Report of the Committee of Infectious Disease, ed 27. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2006.

Steiner MJ, DeWalt DA, Byerley JS. Is this child dehydrated? JAMA. 2004;291(22):2746-2754.

Sundel ER. Abdominal pain and acute abdomen. In: Comprehensive Pediatric Hospital Medicine. Philadelphia: Mosby Elsevier; 2007.