Chapter 46 Gastrointestinal Bleeding in the Critically ill Patient

2 What are hematemesis, coffee-ground emesis, hematochezia, and melena? Are these features helpful in determining the site and rate of bleeding?

Hematemesis is vomiting of fresh, red blood and indicates bleeding in the upper GI tract. Approximately 50% of patients with upper GI bleeding (UGIB) will present with hematemesis.

Hematemesis is vomiting of fresh, red blood and indicates bleeding in the upper GI tract. Approximately 50% of patients with upper GI bleeding (UGIB) will present with hematemesis.

If the blood is older, it can appear like coffee grounds. The return of bright red blood or coffee grounds through a nasogastric tube (NGT) is highly specific for hemorrhage proximal to the ligament of Treitz.

If the blood is older, it can appear like coffee grounds. The return of bright red blood or coffee grounds through a nasogastric tube (NGT) is highly specific for hemorrhage proximal to the ligament of Treitz.

Hematochezia is used to describe passage of bright red or maroon-colored blood through the rectum and typically indicates a lower tract source. Less commonly (< 15%) it may indicate the rapid transit of torrential hemorrhage from the upper tract.

Hematochezia is used to describe passage of bright red or maroon-colored blood through the rectum and typically indicates a lower tract source. Less commonly (< 15%) it may indicate the rapid transit of torrential hemorrhage from the upper tract.

Melena is the passage of black, tarry, and usually foul-smelling stool because of degradation of blood components as they traverse the GI tract. It typically signifies upper GI tract bleeding (70%) or, less often, hemorrhage from the proximal lower tract (30%).

Melena is the passage of black, tarry, and usually foul-smelling stool because of degradation of blood components as they traverse the GI tract. It typically signifies upper GI tract bleeding (70%) or, less often, hemorrhage from the proximal lower tract (30%).

4 What are the most common causes of upper and lower GI bleeding?

See Tables 46-1 and 46-2.

| Cause | Prevalence (%) |

|---|---|

| Peptic ulcer disease | 55 |

| Gastritis-duodenitis | 20 |

| Esophageal varices | 12 |

| Mallory-Weiss tears | 8 |

| Neoplasm | 3 |

| Angiodysplasia | 2 |

Table 46-2 Causes of Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding

| Cause | Prevalence (%) |

|---|---|

| Diverticular disease | 40 |

| Angiodysplasia | 20 |

| Colitis | 20 |

| Anorectal bleeding (hemorrhoids, anal fissures) | 7 |

| Neoplasm | 7 |

| Small bowel bleeding | 6 |

5 What risk factors are associated with higher mortality in patients with upper GI tract hemorrhage?

7 What are the immediate actions that need to be taken in an acute GI tract hemorrhage in the ICU?

Ensure patient has at least two large-bore (at least 18 gauge) intravenous catheters.

Ensure patient has at least two large-bore (at least 18 gauge) intravenous catheters.

Insert Foley and nasogastric catheter (if not already in place), and initiate resuscitation (with crystalloids or blood products) per the local guidelines and policies.

Insert Foley and nasogastric catheter (if not already in place), and initiate resuscitation (with crystalloids or blood products) per the local guidelines and policies.

Consider obtaining a definitive airway in the uncooperative, agitated, or encephalopathic patient at risk for aspiration.

Consider obtaining a definitive airway in the uncooperative, agitated, or encephalopathic patient at risk for aspiration.

Aspirate sample from nasogastric tube and perform rectal examination (attempt to localize the source of bleeding).

Aspirate sample from nasogastric tube and perform rectal examination (attempt to localize the source of bleeding).

If UGIB, initiate medical therapy with intravenous proton pump inhibitors.

If UGIB, initiate medical therapy with intravenous proton pump inhibitors.

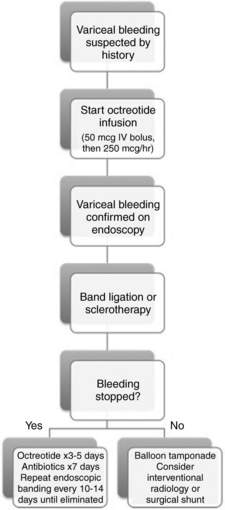

If suspicious of bleeding varices, start an octreotide infusion.

If suspicious of bleeding varices, start an octreotide infusion.

Consult the endoscopy and/or radiology and surgical services as needed.

Consult the endoscopy and/or radiology and surgical services as needed.

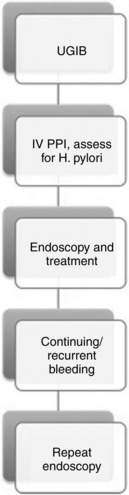

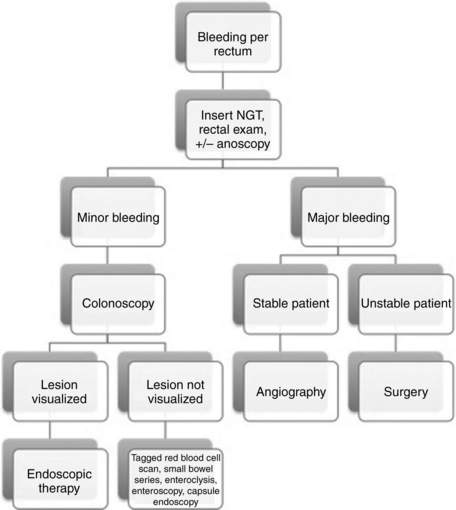

For more details on managing acute GI tract bleeding, see algorithms in Figures 46-1 to 46-3.

For more details on managing acute GI tract bleeding, see algorithms in Figures 46-1 to 46-3.

9 What medical therapies are available for the management of GI bleeding?

Somatostatin analogs: Octreotide is a long-acting somatostatin analog that inhibits glucagon-induced mesenteric vasodilation and has been shown to decrease the risk for persistent bleeding and rebleeding in patients with both variceal and nonvariceal upper tract bleeding. Although somatostatin analogs do not improve mortality rates, they are helpful in reducing bleeding and minimizing transfusion requirements. The recommended dose for octreotide is 250 mcg IV bolus followed by a 250 mcg/hr infusion.

Somatostatin analogs: Octreotide is a long-acting somatostatin analog that inhibits glucagon-induced mesenteric vasodilation and has been shown to decrease the risk for persistent bleeding and rebleeding in patients with both variceal and nonvariceal upper tract bleeding. Although somatostatin analogs do not improve mortality rates, they are helpful in reducing bleeding and minimizing transfusion requirements. The recommended dose for octreotide is 250 mcg IV bolus followed by a 250 mcg/hr infusion.

Proton pump inhibitors (PPI): They have been shown to reduce risk of rebleeding, transfusion requirements, and need for surgical intervention. Their effect on mortality is questionable. They are recommended before endoscopy, as they decrease the likelihood of bleeding or need for intervention during endoscopy. Continuous PPI infusion does not appear to be better than intermittent administration and is less cost-effective. H2-receptor blockers have not proved to be valuable in the management of acute UGIB, as they lack benefit in duodenal ulcers and afford only a weak benefit in bleeding gastric ulcers.

Proton pump inhibitors (PPI): They have been shown to reduce risk of rebleeding, transfusion requirements, and need for surgical intervention. Their effect on mortality is questionable. They are recommended before endoscopy, as they decrease the likelihood of bleeding or need for intervention during endoscopy. Continuous PPI infusion does not appear to be better than intermittent administration and is less cost-effective. H2-receptor blockers have not proved to be valuable in the management of acute UGIB, as they lack benefit in duodenal ulcers and afford only a weak benefit in bleeding gastric ulcers.

Vasopressin: This is a potent vasoconstrictor that has been used extensively for UGIB, most commonly for variceal bleeding. However, its unfavorable safety profile has led to its progressively diminishing use. Common adverse events include a significant rebleeding rate when the infusion is stopped and a high rate of complications (myocardial and peripheral tissue ischemia, dysrhythmias, hypertension, and decreased cardiac output).

Vasopressin: This is a potent vasoconstrictor that has been used extensively for UGIB, most commonly for variceal bleeding. However, its unfavorable safety profile has led to its progressively diminishing use. Common adverse events include a significant rebleeding rate when the infusion is stopped and a high rate of complications (myocardial and peripheral tissue ischemia, dysrhythmias, hypertension, and decreased cardiac output).

23 What is the treatment of IC?

Key Points Gi Bleeding

1. Always insert a nasogastric tube to rule out UGIB, even in cases that present with copious fresh blood from the rectum.

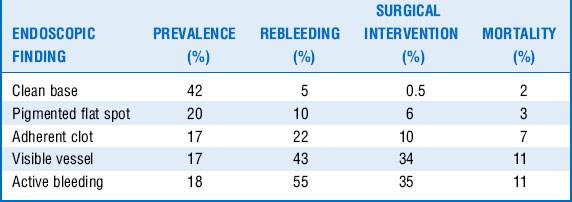

2. Early endoscopy is key in both upper and lower GI tract bleeding for diagnosing, risk-stratifying, localizing, and treating bleeding.

3. Do not forget about stress ulcer prophylaxis in critically ill patients with the appropriate indications. Remember to discontinue it when the indications cease to exist.

4. A systematic approach is key in managing all patients with GI bleeding.

1 Barnert J., Messmann H. Diagnosis and management of lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;6:637–646.

2 Cappell M., Friedel D. Initial management of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding: from initial evaluation up to gastrointestinal endoscopy. Med Clin North Am. 2008;92:491–509.

3 Ferguson C.B., Mitchell R.M. Nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding: standard and new treatment. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2005;34:607–621.

4 Green B.T., Rockey D.C. Lower gastrointestinal bleeding-management. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2005;34:665–678.

5 Laine L., Peterson W.L. Bleeding peptic ulcer. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:717–727.

6 Reissfelder C., Sweiti H., Antolovic D., et al. Ischemic colitis: Who will survive? Surgery. 2011;149:585–592.

7 Rockey D.C. Gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2005;34:581–588.

8 Spirt M.J. Stress-related mucosal disease: risk factors and prophylactic therapy. Clin Ther. 2004;26:197–213.

9 Yüksel I., Ataseven H., Köklü S., et al. Intermittent versus continuous pantoprazole infusion in peptic ulcer bleeding: a prospective randomized study. Digestion. 2008;78:39–43.

10 Zaman A., Chalasani N. Bleeding caused by portal hypertension. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2005;34:623–642.