33 Gastrointestinal Bleeding

• Morbidity and mortality from gastrointestinal bleeding increase significantly if aggressive resuscitation is not initiated immediately in the emergency department.1,2

• Assessment and management of gastrointestinal bleeding depend on the site of the hemorrhage—that is, whether the bleeding is from an upper or lower gastrointestinal tract source.

• Gastroenterology consultation should be obtained immediately to arrange for diagnostic and therapeutic endoscopy or colonoscopy for cases of active bleeding.

• Causes of gastrointestinal bleeding in children vary considerably with age; most cases are benign and self-limited, although Meckel diverticulum, midgut volvulus, and intussusception can result in massive rectal bleeding.

Scope

Demographic risk factors for patients with gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding include older age, male gender, and the use of alcohol, tobacco, aspirin, or nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).3 Risk for bleeding is significantly higher in elderly patients who have recently started a regimen of NSAIDs or regular-dose aspirin than in long-term users of these agents.4 Additional independent risk factors are unmarried status, cardiovascular disease, difficulty performing activities of daily living, use of multiple medications, and use of oral anticoagulants.5

Intensive resuscitation in the emergency department (ED) significantly decreases mortality in patients with hematemesis (vomiting blood), hematochezia (red bloody stools), or melena (black tarry stools).2 Application of the predictive mnemonic BLEED (ongoing bleeding, low systolic blood pressure, elevated prothrombin time, erratic mental status, unstable comorbid disease) at the initial ED evaluation can predict hospital outcomes in patients with acute upper or lower GI hemorrhage.6 Although the incidence of peptic ulcer bleeding has decreased, the decline in incidence has occurred only in patients younger than 70 years,7 and mortality from multiorgan failure, cardiopulmonary conditions, or terminal malignancy has remained constant.1

Lower GI bleeding (LGIB) afflicts 20 to 27 of every 100,000 persons annually in the United States.8 The rate of LGIB increases more than 200-fold from the third to the ninth decade of life, with 25% to 35% of all cases occurring in elderly patients. It is one of the common medical emergencies that can become life-threatening in elderly patients.9,10 Risk stratification for LGIB by Strate et al. has identified seven predictors of severe bleeding: heart rate higher than 100 beats/min, systolic blood pressure lower than 115 mm Hg, syncope, nontender abdominal examination, gross rectal bleeding, aspirin use, and more than two comorbid conditions. Patients with more than three risk factors have an 84% risk for severe bleeding, defined as transfusion of more than 2 units of red blood cells.11–13

Pediatric GI bleeding is fairly common worldwide; however, the incidence of severe GI bleeding in U.S. children is very low.14 LGIB is a more common complaint in the practice of general pediatrics, and it accounts for 10% to 15% of referrals to a pediatric gastroenterologist.15–17 In most children, bleeding is not life-threatening and ceases spontaneously, with only supportive care being required.16,17 The age of the child guides the clinician toward specific diagnoses.16,18

Pathophysiology

Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding

Tips and Tricks

Patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding should be instructed to avoid nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).19,20 Studies have shown that the risk for recurrent bleeding is significantly higher in long-term users of NSAIDs or regular-dose aspirin, especially if patients are elderly. For short-term users of NSAIDs or aspirin, cotreatment with proton pump inhibitors (but not with histamine H2 blockers) may reduce the risk for bleeding to less than the risk in nonusers.4

Hematochezia is generally a symptom of LGIB but may be associated with brisk upper tract hemorrhage. UGIB sources are identified in 11% of patients in whom LGIB was initially suspected.3 Melena most commonly results from bleeding proximal to the jejunum and should be considered a marker of UGIB.

Variceal hemorrhage is the most serious complication of portal hypertension and occurs in one third of patients with esophageal varices.3 It is more common in patients with Child B and C cirrhosis.21 The extent of severe bleeding depends on portal pressure, variceal size, and variceal wall thickness.22 Esophageal varices should be suspected in any alcoholic with unexplained anemia or obvious GI bleeding.

One study noted a decline in the frequency of peptic ulcer disease in patients with UGIB and reported that the proportion of bleeding ulcers with a nonvisible vessel is now 20%, which is less than previously reported.23 Such decline may be related to improved treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection.

In children, the pathophysiology of the bleeding is determined by the specific causes of hemorrhage for each age group.24

Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding

LGIB refers to bleeding that originates from an intestinal source distal to the ligament of Treitz. The majority of patients with hematochezia bleed from a colonic source. Diverticular disease, angiodysplasia, and neoplasm are the leading causes of LGIB in adults. Anal fissure and hemorrhoids are the most benign causes of LGIB. Approximately 10% of all patients will never have a source identified, and up to 40% of patients with LGIB have more than one potential bleeding source.11

Comorbid illnesses and decreased physiologic reserve make elderly patients more vulnerable to the adverse consequences of acute blood loss and prolonged hospitalization.10,25 Specifically, hematochezia is more commonly associated with syncope, dyspnea, altered mental status, stroke, falls, fatigue, and acute anemia in older patients. Poor prognostic indicators also include continued bright red rectal bleeding, excessive transfusions, orthostasis, shock, and altered mental status on admission.9

![]() Red Flags

Red Flags

Data from Swaim M, Wilson J. GI emergencies: rapid therapeutic responses for older patients. Geriatrics 1999;54:20.

Ulcerative colitis accounts for the majority of cases of massive LGIB in young adults in the second or third decade of life. Diverticulosis and arteriovenous malformation are found in older adults.15

The independent risk factors listed earlier are useful prognostic indicators, and outcomes are poorer in patients with either upper or lower tract bleeding.5 Specifically, use of over-the-counter NSAIDs may represent an important cause of peptic ulcer disease and ulcer-related hemorrhage in those with UGIB.4,26

Although most causes of LGIB in children are self-limited and benign, it is imperative to consider Meckel diverticulum, midgut volvulus, and intussusception in appropriate age groups.15

Clinical Presentation

Patients with GI bleeding can be rapidly assessed by their reported volume of blood loss and initial hemodynamic status. Massive hemorrhage is associated with signs or symptoms of hemodynamic instability, including tachycardia (heart rate greater than 100 to 120 beats/min), systolic blood pressure less than 90 to 100 mm Hg, symptomatic orthostasis, syncope, ongoing bright red or maroon hematemesis, transfusion requirements in the first 24 hours, and inability to stabilize the patient.27

Vital signs and postural changes should be assessed in patients who appear sufficiently stable. An increase of 20 beats/min or more in pulse or a decrease of 20 mm Hg in systolic blood pressure between the supine and upright positions indicates loss of more than 20% of blood volume in normal adult patients.9 Tachycardia, low blood pressure, reduced urine output, and conjunctival pallor in patients with GI bleeding are signs that mandate immediate volume replacement. Hypovolemic shock implies at least a 40% loss of blood volume. Note that abnormalities in vital signs, especially postural vital sign, are unreliable in pediatric and elderly patients.

Complaints associated with LGIB include hematochezia or melena, although patients may have additional findings, such as anemia, light-headedness, hypovolemia, weakness, malaise, chest pain, and dyspnea. It is important to note that patients with LGIB may be asymptomatic and have complaints seemingly unrelated to intestinal bleeding (e.g., fatigue, weight loss); dramatic findings consisting of massive rectal bleeding in acutely ill and unstable patients are less common.28

Delayed black tarry stools may occur from a source of bleeding in the small bowel or ascending colon and may not be noted by the patient until several days after the bleeding has stopped.29

Food allergy may lead to GI bleeding from food-induced colitis and could result in dehydration in infants younger than 3 months.17 Anal fissures are common in infants and produce red streaks or spots of blood in the diaper.15 Other causes of dark stool are iron, charcoal, flavored gelatin, red fruits, bismuth, and food dyes. Maternal blood swallowed by neonates during delivery may be diagnosed with the Apt test.17

Differential Diagnosis

The most common causes of UGIB in adults are listed in Box 33.1, and causes of LGIB in adolescents and adults are listed in Box 33.2.

Box 33.1

Causes of Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding

From Maltz C. Acute gastrointestinal bleeding. Best Pract Med 2003:1-23. Available at http://merck.microdex.com/index.asp?page=bpm_brief&article_id=BPM01GA08.

Box 33.2

Causes of Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding

From Akhtar AJ. Lower gastrointestinal bleeding in elderly patients. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2003;4:320-2.

An aortoenteric fistula may have developed in a patient with massive LGIB and recent surgery.9

Differential Diagnosis for Pediatric Gastrointestinal Bleeding

Table 33.1 lists the differential diagnosis for UGIB and LGIB according to patient age. Ingestion of maternal blood is the most common cause of suspected GI bleeding in neonates; blood is swallowed during either delivery or breastfeeding (from a fissure in the mother’s breast). Other causes of GI bleeding in neonates include bacterial enteritis, milk protein allergies, intussusception, anal fissures, lymphonodular hyperplasia, and erosions of the esophageal, gastric, and duodenal mucosa.

Table 33.1 Causes of Gastrointestinal (GI) Bleeding in Children by Age

| AGE GROUP | CAUSES OF UPPER GI BLEEDING | CAUSES OF LOWER GI BLEEDING |

|---|---|---|

| Neonates |

From Arensman R, Abramson L. Gastrointestinal bleeding: surgical perspective. EMedicine 2004. Available at www.emedicine.com/ped/topic3027.htm.

Rarer causes of GI bleeding in a neonate are volvulus, coagulopathies, arteriovenous malformations, necrotizing enterocolitis (especially in preterm infants), Hirschsprung enterocolitis, and Meckel diverticulitis.14

Older children may have any of the preceding conditions, but duodenal ulcer, Mallory-Weiss tear, and nasopharyngeal bleeding are important causes of bleeding in this age group. Less common causes are gastritis or ulcers induced by salicylates or NSAIDs, Henoch-Schönlein purpura, ingestion of caustic substances, hemolytic-uremic syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease, and vasculitis. In adolescents older than 12 years, the most common causes of UGIB are duodenal ulcers, esophagitis, gastritis, and Mallory-Weiss tears.14

Diagnostic Testing

Nasogastric Aspiration

Historically, nasogastric aspiration has been used to determine whether the bleeding originated from the upper GI tract in patients with melena—a bloody aspirate confirmed an upper tract source, whereas an aspirate testing negative for blood represented either resolved bleeding or a more distal site of hemorrhage. In some studies, however, nasogastric aspiration was noted to be insensitive for detection of UGIB in patients without active hematemesis, and a negative result provided little information about the cause of the bleeding.30,31 The routine use of gastric aspiration and lavage in patients arriving at the ED with GI bleeding is not supported.32 Aspirates testing positive for blood confirm only that the bleeding is proximal to the pylorus, and patients must undergo endoscopy for further differentiation.

A nasogastric aspirate containing more than 1 L of fresh blood or inability to obtain a clear aspirate through lavage with more than 1500 mL of saline should alert the physician to massive UGIB that requires immediate gastroenterologic or surgical intervention. In patients with frank hematemesis and brisk persistent hematochezia, the information provided by nasogastric aspiration may be lifesaving.33

Upper Endoscopy

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) is now the diagnostic test of choice for establishing the source of UGIB. The overwhelming majority of existing data suggest that early endoscopy is a safe and effective procedure in all risk groups.34,35 Patients without active hematemesis may benefit from immediate upper endoscopy by a gastroenterologist to confirm the site of bleeding rather than undergoing the potential additional discomfort and morbidity associated with placement of a nasogastric tube. Endoscopy is both diagnostic and therapeutic in many cases.36 One study noted that live-view video capsule endoscopy (VCE) accurately indentifies high- and low-risk patients in the ED with UGIB. The use of VCE to risk-stratify these patients significantly reduced time to performance of emergency EGD and therapeutic intervention.37

Tagged Red Blood Cell Studies

An advanced modality for detecting of the source of GI bleeding is radionuclide imaging, such as radioisotopic imaging with technetium Tc 99m sulfur colloid– or technetium pertechnetate–labeled red blood cells. Technetium Tc 99m red blood cell imaging is a useful test in the management of acute GI bleeding, particularly if the bleeding has been occurring for more than 3 hours and other modalities have failed to identify a source. A limitations of this test is poor detection of bleeding in the foregut, with the highest sensitivity noted for bleeding in the colon.38 A technetium Tc 99m sulfur colloid–labeled red blood cell study requires active bleeding at a rate of more than 0.1 mL/min for visualization. Radionuclide imaging has not been widely tested in the ED setting and is still reserved for inpatient use at most institutions.

Arteriography

Angiography is appropriate for initial testing of patients with massive bleeding.39 When the bleeding cannot be identified and controlled by endoscopy, intraoperative enteroscopy or arteriography may help localize the bleeding source and facilitate segmental resection of the bowel.40 Mesenteric angiography can detect bleeding at a rate of 0.5 mL/min or greater.41 Either angiography or angiographic computed tomography may be used to identify aortoenteric fistulas.

Intraarterial injection of vasopressin or other vasoconstrictors at the site of bleeding can control hemorrhage; embolization is an option when intraarterial injection is unsuccessful.42,43

Distal Colonic Imaging

Colonoscopy has high diagnostic yield and a low rate of perforation in patients with LGIB. It is best performed after colonic cleansing and in patients with slow bleeding. Proctosigmoidoscopy is used in patients with mild rectal bleeding to determine whether stool above the rectum contains blood. Barium enema is not useful in the acute setting but can be ordered after an acute bleeding episode has resolved.44

The optimal timing for colonoscopic intervention for LGIB is still unclear.10 More recent literature defines urgent colonoscopy as taking place within 12 hours.45 Evidence suggests that earlier colonoscopy leads to more diagnostic and therapeutic opportunities45 and reduces hospital length of stay.10,12,45

Multidetector Computed Tomography Technology

Multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) can be used to evaluate both acute and obscure (recurrent or persistent) GI tract bleeding. Initial experience indicates that MDCT angiography is a promising first-line modality that is time efficient and sensitive and allows accurate diagnosis or exclusion of active GI hemorrhage. The potential for an impact on the evaluation and treatment of patients with acute GI bleeding is notable.46,47

Laboratory Testing

Initial laboratory studies include a complete blood cell count, coagulation studies, and blood typing and crossmatching for patients with active bleeding or unstable vital signs. Serial hematocrit measurements are more useful than one isolated test, although marked changes in hematocrit typically lag behind actual blood loss. A blood chemistry panel, liver profile, and lipase measurement should be performed. Stool evaluation for leukocytes, bacteria, ova, parasites, and Clostridium difficile should be considered in patients with bloody diarrhea.17 Electrocardiograms and cardiac enzyme testing are necessary for patients at risk for early coronary artery disease or those older than 50 years to screen for ischemia secondary to blood loss.

Procedures

Proper technique for the safe placement and use of nasogastric tubes and gastroesophageal balloon tamponade tubes (e.g., Blakemore-Sengstaken tube) is discussed in Chapter 46.

Treatment

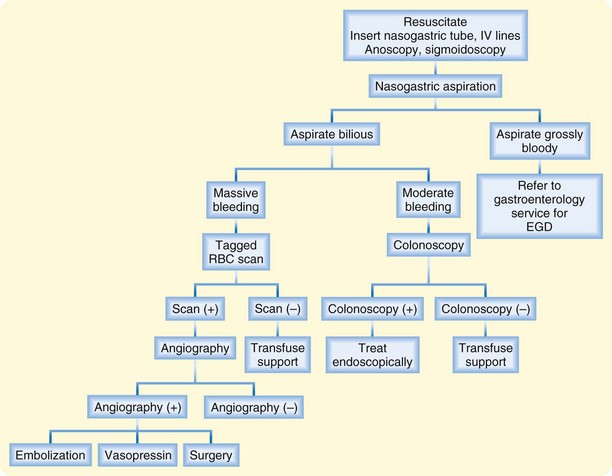

Figure 33.1 presents an algorithm for the treatment of GI bleeding. Insert two 18-gauge or larger intravenous lines and administer 0.9% normal saline or lactated Ringer solution on arrival of the patient.41 Quickly evaluate the patient’s hemodynamic status and determine the extent of blood or fluid resuscitation necessary. Standard resuscitative measures for the management of shock should precede or occur in parallel with definitive diagnostic testing. Management should otherwise be directed toward the underlying source of bleeding. Note that in 80% of cases, LGIB spontaneously stops.25

Fig. 33.1 Management of lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage.

(Adapted from Hoedema RE, Luchtefeld MA. The management of lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Dis Colon Rectum 2005;48:2010-24.)

If the patient is hemorrhaging, consult a gastroenterologist and surgeon. Upper endoscopy is the diagnostic and therapeutic procedure of choice for acute UGIB. Surgery is indicated for patients with active bleeding when medical therapy proves ineffective and continued hemorrhage requires more than 5 units of blood within the first 4 to 6 hours.28,29,41,48 Bowel resection may be required for pronounced LGIB.

![]() Patient Teaching Tips

Patient Teaching Tips

Patients should stop drinking alcohol and seek an alcohol cessation program immediately if needed.

Patients who take nonsteroidal antiinflammatory agents should receive concomitant therapy with a proton pump inhibitor.

Patients with gastric ulcers should be reexamined 6 to 8 weeks after the initial bleeding episode.

Patients should maintain daily intake of synthetic bulk-forming agents.

Surveillance colonoscopy should be performed every 3 years in patients with colon polyps and adenomatous changes or every 5 years in those with hyperplastic polyps.

Data from Swaim M, Wilson J. GI emergencies: rapid therapeutic responses for older patients. Geriatrics 1999;54:20.

Disposition

Patients with normal physical findings, trace heme-positive stool, and stable vital signs may be sent home with close follow-up. Patients with reported hematochezia but normal-appearing stool and no evidence of hemodynamic compromise may be managed as outpatients with arrangements for urgent colonoscopy and primary care referral.41

Patients who have anal fissures, hemorrhoids, or other rectal causes of bleeding can be discharged with conservative therapy and reassurance. A detailed discussion of the management of anorectal disorders can be found in Chapter 41.

Patients should be instructed to return to the ED if they experience signs and symptoms of recurrent bleeding, fatigue, chest discomfort, dyspnea, or near-syncope.49

Manning-Dimmitt LL, Dimmitt SG, Wilson GR. Diagnosis of gastrointestinal bleeding in adults. Am Fam Physician. 2005;71:1339–1346.

Peter D, Dougherty J. Evidence based emergency medicine: evaluation of the patient with gastrointestinal bleeding: an evidence based approach. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 1999;17:239–261.

Pitera A, Sarko J. Just say no: gastric aspiration and lavage rarely provide benefit. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;55:365–366.

Spiegel BM. Endoscopy for acute upper GI tract hemorrhage: sooner is better. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:236–239.

1 Lanas A. Upper GI bleeding—associated mortality: challenges to improving a resistant outcome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:90–92.

2 Baradarian R, Ramdhaney S, Chapalamadugu R, et al. Early intensive resuscitation of patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding decreases mortality. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:619–622.

3 Peura DA, Lanza FL, Gostout CJ, et al. The American College of Gastroenterology Bleeding Registry: preliminary findings. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:924–928.

4 Pilotto A, Franceschi M, Leandro G, et al. The risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in elderly users of aspirin and other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: the role of gastroprotective drugs. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2003;15:494–499.

5 Kaplan RC, Heckbert SR, Koepsell TD, et al. Risk factors for hospitalized gastrointestinal bleeding among older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:126–133.

6 Kollef MH, O’Brien JD, Zuckerman GR, et al. BLEED: a classification tool to predict outcomes in patients with acute upper and lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Crit Care Med. 1997;25:1125–1132.

7 Loperfido S, Baldo V, Piovesana E, et al. Changing trends in acute upper-GI bleeding: a population-based study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:212–224.

8 Brackman MR, Gushchin VV, Smith L, et al. Acute Lower Gastroenteric Bleeding Retrospective Analysis (the ALGEBRA study): an analysis of the triage, management and outcomes of patients with acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Am Surg. 2003;69:145–149.

9 Akhtar AJ. Lower gastrointestinal bleeding in elderly patients. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2003;4:320–322.

10 Strate LL. Lower GI bleeding: epidemiology and diagnosis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2005;34:643–664.

11 Lee J, Costantini TW, Coimbra R. Acute lower GI bleeding for the acute care surgeon: current diagnosis and management. Scand J Surg. 2009;98:135–142.

12 Strate LL, Orav EJ, Syngal S. Early predictors of severity in acute lower intestinal tract bleeding. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:838–843.

13 Strate LL, Saltzman JR, Ookubo R, et al. Validation of a clinical prediction rule for severe acute lower intestinal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1821–1827.

14 Hsai R, Wang N, Halpern J, et al. Pediatrics, gastrointestinal bleeding. EMedicine. 2005.

15 Arensman R, Abramson L. Gastrointestinal bleeding: surgical perspective. EMedicine. 2004.

16 Fox VL. Gastrointestinal bleeding in infancy and childhood. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2000;29:37–66. v

17 Leung AK, Wong AL. Lower gastrointestinal bleeding in children. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2002;18:319–323.

18 Arain Z, Rossi TM. Gastrointestinal bleeding in children: an overview of conditions requiring nonoperative management. Semin Pediatr Surg. 1999;8:172–180.

19 Blot WJ, McLaughlin JK. Over the counter non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of gastrointestinal bleeding. J Epidemiol Biostat. 2000;5:137–142.

20 Thomas J, Straus WL, Bloom BS. Over-the-counter nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of gastrointestinal symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2215–2219.

21 Sorbi D, Gostout CJ, Peura D, et al. An assessment of the management of acute bleeding varices: a multicenter prospective member-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2424–2434.

22 Roberts L, Kamath P. Pathophysiology of variceal bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 1999;2:167–174.

23 Boonpongmanee S, Fleischer DE, Pezzullo JC, et al. The frequency of peptic ulcer as a cause of upper-GI bleeding is exaggerated. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:788.

24 Lazzaroni M, Petrillo M, Tornaghi R, et al. Upper GI bleeding in healthy full-term infants: a case-control study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:89–94.

25 Swaim M, Wilson J. GI emergencies: rapid therapeutic responses for older patients. Geriatrics. 1999;54:20.

26 Wilcox CM, Shalek KA, Cotsonis G. Striking prevalence of over-the-counter nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use in patients with upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154:42–46.

27 Peter D, Dougherty J. Evidence based emergency medicine: evaluation of the patient with gastrointestinal bleeding: an evidence based approach. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 1999;17:239–261.

28 Hoedema RE, Luchtefeld MA. The management of lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:2010–2024.

29 Vernava AM, 3rd., Moore BA, Longo WE, et al. Lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40:846–858.

30 Cuellar RE, Gavaler JS, Alexander JA, et al. Gastrointestinal tract hemorrhage. The value of a nasogastric aspirate. Arch Intern Med. 1990;150:1381–1384.

31 Witting MD, Magder L, Heins AE, et al. Usefulness and validity of diagnostic nasogastric aspiration in patients without hematemesis. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;43:525.

32 Pitera A, Sarko J. Just say no: gastric aspiration and lavage rarely provide benefit. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;55:365–366.

33 Anderson RS, Witting MD. Nasogastric aspiration: a useful tool in some patients with gastrointestinal bleeding. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;55:364–365.

34 Dam JV, Brugge WR. Endoscopy of the upper gastrointestinal tract. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1738–1748.

35 Spiegel BM, Vakil NB, Ofman JJ. Endoscopy for acute nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal tract hemorrhage: is sooner better? A systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:1393–1404.

36 Spiegel BM. Endoscopy for acute upper GI tract hemorrhage: sooner is better. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:236–239.

37 Rubin M, Hussain SA, Shalomov A, et al. Live view video capsule endoscopy enables risk stratification of patients with acute upper GI bleeding in the emergency room: a pilot study. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:786–791.

38 Howarth DM, Tang K, Lees W. The clinical utility of nuclear medicine imaging for the detection of occult gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Nucl Med Commun. 2002;23:591–594.

39 Suzman MS, Talmor M, Jennis R, et al. Accurate localization and surgical management of active lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage with technetium-labeled erythrocyte scintigraphy. Ann Surg. 1996;224:29–36.

40 Manning-Dimmitt LL, Dimmitt SG, Wilson GR. Diagnosis of gastrointestinal bleeding in adults. Am Fam Physician. 2005;71:1339–1346.

41 Cagir B, Cirincione E. Lower gastrointestinal bleeding, surgical treatment. EMedicine. 2009.

42 Gady JS, Reynolds H, Blum A. Selective arterial embolization for control of lower gastrointestinal bleeding: recommendations for a clinical management pathway. Curr Surg. 2003;60:344.

43 Khanna A, Ognibene SJ, Koniaris LG. Embolization as first-line therapy for diverticulosis-related massive lower gastrointestinal bleeding: evidence from a meta-analysis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2005;9:343–352.

44 Zuckerman GR, Prakash C. Acute lower intestinal bleeding. Part II: etiology, therapy, and outcomes. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49:228–238.

45 Jensen DM, Machicado GA, Jutabha R, et al. Urgent colonoscopy for the diagnosis and treatment of severe diverticular hemorrhage. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:78–82.

46 Liang HH, Wang W, Wei PL. Unusual cause of lower GI bleeding. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:e7–e8.

47 McSweeney SE, O’Donoghue PM, Jhaveri K. Current and emerging techniques in gastrointestinal imaging. J Postgrad Med. 2010;56:109–116.

48 Messmann H. Lower gastrointestinal bleeding—the role of endoscopy. Dig Dis. 2003;21:19.

49 Zuccaro G, Jr. Management of the adult patient with acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding. American College of Gastroenterology. Practice Parameters Committee. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:1202–1208.