CHAPTER 35 Gastrointestinal and Hepatic Manifestations of Systemic Diseases

RHEUMATOLOGIC AND COLLAGEN VASCULAR DISEASES

Rheumatologic diseases encompass a wide variety of clinical syndromes and are frequently associated with gastrointestinal abnormalities (Table 35-1). In addition, the medications used to treat these diseases often produce gastrointestinal and hepatic toxicity. This section focuses on the more common abnormalities that may be encountered by the gastroenterologist.

Table 35-1 Gastrointestinal Manifestations of Rheumatologic Diseases

| DISEASE | ABNORMALITY/ASSOCIATION | CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS |

|---|---|---|

| Rheumatoid arthritis | Temporomandibular arthritis | Impaired mastication |

| Esophageal dysmotility | Dysphagia, GERD | |

| Visceral vasculitis | Abdominal pain, cholecystitis, intestinal ulceration and infarction | |

| Amyloidosis | Pseudo-obstruction, malabsorption, protein-losing enteropathy, intestinal ulceration and infarction, gastric outlet obstruction | |

| Portal hypertension (Felty’s syndrome) | Variceal hemorrhage | |

| Gold enterocolitis | Enteritis, diarrhea, fever, eosinophilia, megacolon | |

| Scleroderma | Esophageal dysmotility | Dysphagia, GERD, stricture, Barrett’s esophagus |

| Gastroparesis | Gastric retention, GERD | |

| Intestinal fibrosis and dysmotility | Constipation, pseudo-obstruction, malabsorption, intussusception, volvulus, pneumatosis intestinalis | |

| Pseudodiverticula | Hemorrhage, stasis, bacterial overgrowth | |

| Arteritis (rare) | Mesenteric thrombosis, infarction, pancreatic necrosis | |

| Pancreatitis | Calcific pancreatitis, pancreatic exocrine insufficiency | |

| SLE | Esophageal dysmotility | Dysphagia, reflux |

| Mesenteric vasculitis | GI ulceration, intestinal infarction, intussusception, pancreatitis, pneumatosis intestinalis | |

| Sjögren’s syndrome | Desiccation of membranes | Oral fissures, oropharyngeal dysphagia |

| Esophageal webs | Dysphagia | |

| Gastric lymphoid infiltrates | ||

| Pancreatitis | Abdominal pain, pancreatic exocrine insufficiency | |

| Primary biliary cirrhosis | Jaundice, hepatic failure, variceal hemorrhage | |

| Polymyositis-dermatomyositis | Skeletal muscle dysfunction | Aspiration, impaired glutition |

| Dysmotility | Dysphagia, GERD, gastroparesis, constipation, diverticula | |

| Mesenteric vasculitis (rare) | GI ulceration, perforation, pneumatosis intestinalis | |

| MCTD | Dysmotility | Dysphagia, GERD, stricture, gastroparesis, bezoars, pseudo- obstruction |

| PAN | Mesenteric vasculitis (rare) | Ulceration, perforation, pancreatitis |

| Mesenteric vasculitis | Cholecystitis, appendicitis, intestinal infarction, pancreatitis, perforation, strictures, mucosal hemorrhage, submucosal hematomas | |

| CSS | Mesenteric vasculitis | Hemorrhage, ulceration, intestinal infarction, perforation |

| Eosinophilic gastritis | Gastric masses | |

| Henoch-Schönlein purpura | Mesenteric vasculitis | Intussusception, ulcers, cholecystitis, hemorrhage, intestinal infarction, appendicitis, perforation |

| Kohlmeier-Degos disease | Mesenteric vasculitis | Hemorrhage, ulceration, intestinal infarction, malabsorption |

| Cogan’s syndrome | Mesenteric vasculitis (infrequent) | Hemorrhage, ulceration, intestinal infarction, intussusception |

| Crohn’s disease | Bloody diarrhea, abdominal pain, fissures, fistulas | |

| Wegener’s granulomatosis | Mesenteric vasculitis | Cholecystitis, appendicitis, ileocolitis, intestinal infarction |

| Cryoglobulinemia | Mesenteric vasculitis (rare) | Intestinal infarction, ischemia |

| Behçet’s disease | Mucosal ulcerations | Hemorrhage, perforation, pyloric stenosis |

| Complications as in rheumatoid arthritis | ||

| Reactive arthritis | Ileocolonic inflammation | Usually asymptomatic |

| Familial Mediterranean fever | Serositis/peritonitis, amyloidosis, PAN, Henoch-Schönlein purpura | Abdominal pain, fever, dysmotility |

| Marfan/Ehlers-Danlos syndromes | Defective collagen | Megaesophagus, hypomotility, diverticula, megacolon, malabsorption, perforation, arterial rupture |

CSS, Churg-Strauss syndrome; GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease; GI, gastrointestinal; MCTD, mixed connective tissue disease; PAN, polyarteritis nodosa; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus.

RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS

Approximately 0.8% of adults worldwide are affected with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), which is a chronic, inflammatory autoimmune disease primarily targeting the synovial tissues with systemic manifestations. Oropharyngeal symptoms may occur in patients with RA as a result of xerostomia, temporomandibular joint (TMJ) arthritis, cervical spine abnormalities, and laryngeal involvement.1 Esophageal dysmotility, characterized by low-amplitude peristaltic waves, has been described in the proximal, middle, and distal esophagus with reduced lower esophageal sphincter (LES) pressure.1,2 Rheumatoid vasculitis typically occurs in the setting of severe RA with rare gastrointestinal manifestations such as ischemic cholecystitis or appendicitis, ulceration, pancolitis, infarction, or intra-abdominal hemorrhage due to a ruptured visceral aneurysm.3,4 Other gastrointestinal complications of RA include amyloidosis (discussed later) and malabsorption. Felty’s syndrome–RA, splenomegaly, and leukopenia have been associated with severe infections, portal hypertension, and variceal hemorrhage.5

Hepatic Abnormalities

Abnormal liver function tests, especially elevations of serum alkaline phosphatase of hepatobiliary origin,6–8 are commonly observed in patients with RA. In one large series of patients with RA,6 18% had elevated levels of serum alkaline phosphatase and 11% were found to have hepatomegaly. Fluctuations in serum alkaline phosphatase levels have also been reported to correlate with disease activity.6,8 However, degrees of alkaline phosphatase elevations are usually modest, with the mean level being less than two-fold abnormal.6 Furthermore, other clinical signs of liver disease are usually absent, and liver biopsy and autopsy studies have not revealed any consistent or specific findings, with the most common abnormalities being fatty change, Kupffer cell hyperplasia, and mild mononuclear cell infiltration of the portal tracts or rare parenchymal foci of hepatocyte necrosis.6,9–11 Periportal fibrosis is also present in a small minority of cases.11 Determination of etiology of hepatic dysfunction in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis is complicated by the fact that many of the agents commonly used as therapy for this disease have known potential for liver injury.7,10–12

In a small subset of patients with RA and/or Sjögren’s syndrome, antimitochondrial antibodies are present along with the biochemical and histologic features of primary biliary cirrhosis.13–15 The incidence of primary biliary cirrhosis or autoimmune hepatitis appears to be much higher in patients with Sjögren’s syndrome alone than in those with Sjögren’s RA.16,17

Because chronic hepatitis C and RA are relatively common diseases of adults, it is not surprising that these entities are found concurrently in some patients. However, in addition, it has been noted that 75% of individuals with chronic hepatitis C infection develop rheumatoid factors,18 and a subset of these rheumatoid factor–positive individuals develop essential mixed cryoglobulinemia that may be manifested in part by development of arthralgias.19,20 Liver disease in such individuals is often asymptomatic and biochemical abnormalities modest or even absent.19,20 Thus some individuals with essential mixed cryoglobulinemia associated with chronic hepatitis C infection may instead be labeled as having RA. However, anticyclic citrulinated peptide (CCP) antibodies are rarely found in subjects with chronic hepatitis C and nonspecific rheumatologic manifestations and thus anti-CCP antibodies appear to be reliable markers of RA.21 Most rheumatic disease patients with progressive liver disease have concomitant chronic viral or autoimmune hepatitis.22 In patients with concomitant hepatitis B infection, the intermittent use of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors or other immunosuppressive therapy may be associated with severe flares of hepatitis B23–25 and prophylactic use of antiviral therapy should be considered.25 TNF inhibitor therapy in RA also has been associated with flares of severe liver disease, with characteristics of autoimmune hepatitis.26

Perhaps the most distinctive association between RA and hepatic abnormalities is seen in another subset of patients who develop splenomegaly and neutropenia (Felty’s syndrome). Felty’s syndrome is associated with an even higher incidence of hepatomegaly and liver function test abnormalities than seen in uncomplicated RA.27,28 However, there is little correlation between serum hepatic enzyme abnormalities and histopathologic findings.27,28 Nevertheless, more than half of patients with this syndrome have been found to have hepatic histologic abnormalities that range from sinusoidal lymphocytosis and portal fibrosis to the more distinctive picture of nodular regenerative hyperplasia, which has been reported on multiple occasions in patients with Felty’s syndrome27–30 and in one small prospective series was found to be present in 5 of 18 (28%) patients. Hepatic encephalopathy or other manifestations of liver failure have not been reported in patients with Felty’s syndrome, and nodular regenerative hyperplasia but portal hypertension and esophageal variceal hemorrhage may occur.28–30

Gastrointestinal Abnormalities

The most common gastrointestinal problems encountered in patients with RA are due to drug therapy with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), glucocorticoids, and disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs). NSAIDs are most commonly associated with upper gastrointestinal complications such as perforation, ulcers, and bleeding (see Chapters 52 and 53). Less commonly recognized complications of NSAIDs include pill esophagitis (Chapter 45), small bowel ulceration (Chapter 115), strictures of the small and large intestine, and exacerbations of diverticular disease and inflammatory bowel disease.31 Significant risk factors for the development of serious upper gastrointestinal events in patients with RA include NSAIDs therapy, age older than 65 years, history of peptic ulcer disease, glucocorticoid therapy, and severe RA.32,33 In patients with RA, the use of certain selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors results in a lower incidence of gastrointestinal complications than that seen with nonselective NSAIDs.34,35 Helicobacter pylori and NSAIDs are independent and possibly synergistic risk factors for peptic ulceration. As such, chronic NSAID users who develop ulcers should be assessed for H. pylori infection and undergo eradication therapy when infection is present.32,33 Although hypergastrinemia has been reported in patients with RA, the incidence of peptic ulcers is no greater than that seen in patients with osteoarthritis.36 As reviewed in Chapter 53, NSAID-associated gastric and duodenal ulcers can be prevented with misoprostol, high-dose histamine (H2) blockers, and proton pump inhibitors.37 Once identified, ulcers may be treated successfully using proton pump inhibitors despite continued NSAID therapy. In the subgroup of patients with a history of bleeding ulcers, therapy with cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors rather than NSAIDs may be cost effective and less expensive than combining an NSAID with a proton pump inhibitor.38,39

Synthetic DMARDs such as gold and penicillamine are rarely used because of toxicity and marginal efficacy.40 Gold, parenteral as well as oral forms, has been associated with diarrhea, enterocolitis, toxic megacolon, and death. The onset of gold colitis usually occurs within several weeks after the start of therapy and is manifested by nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and fever. Although the colon is most commonly involved, gold-induced gastrointestinal toxicity may affect the esophagus, stomach, and small bowel, with 25% of patients developing a peripheral eosinophilia.41 Treatment includes dose reduction or discontinuation of gold, antidiarrheals, glucocorticoids, cromolyn sodium, or the chelating agent dimercaprol.41,42

Leflunomide, a synthetic DMARD that inhibits pyrimidine synthesis, can cause diarrhea in up to 32% of patients.43 It may also cause severe hepatic toxicity (see Chapter 86). Biologic DMARDs, which inhibit the action of TNF-α (infliximab, etanercept, and adalimumab) or interleukin-1 (IL-1; anakinra), have not shown significant gastrointestinal adverse effects but may cause hepatic toxicity on occasion (see later).

ADULT-ONSET STILL’S DISEASE

Adult-onset Still’s disease, the adult form of juvenile RA, often has gastrointestinal manifestations such as weight loss, sore throat, hepatosplenomegaly, elevated aminotransferases, and abdominal pain, in addition to fever.44 In contrast to the lack of significant hepatic dysfunction in classic rheumatoid arthritis, adults with Still’s disease present with features of mild hepatitis in the majority of cases and life-threatening acute liver failure in exceptional cases.45–49 Variable degrees of aminotransferase and alkaline phosphatase elevations are typically observed in such patients during symptomatic disease flares. Liver biopsies usually reveal moderate portal mononuclear cell infiltration with occasional evidence of focal hepatocyte necrosis.46 Biopsies obtained in patients with jaundice and biochemical evidence of severe hepatitis have been found to have interface and lobular hepatitis with lymphoplasmocytic inflammation reminiscent of autoimmune hepatitis.49 Most cases of severe hepatitis have been observed in patients previously treated with salicylates or other NSAIDs,46,49 but liver enzyme abnormalities are also commonly noted prior to therapy. Some patients with severe hepatitis have been reported to respond to immunosuppressive therapy,49 whereas others required liver transplantation or have died of liver failure.45,47–49 Although severe hepatitis is a rare complication of adult-onset Still’s disease, liver failure appears to be the most common cause of death related to this disease.45

PROGRESSIVE SYSTEMIC SCLEROSIS

Gastrointestinal manifestations occur in up to 90% of patients with PSS.50 Gastrointestinal tract involvement can occur from the mouth to the anus. Atrophy and fibrosis of the perioral skin may limit mandibular motion. The periodontal ligament may become hypertrophic, and the gingivae, tongue papillae, and buccal mucosa may become friable and atrophic, resulting in impaired sensation and taste.

The esophagus is the most frequently involved gastrointestinal organ.50 On pathology, atrophy of smooth muscle layers and intimal proliferation of arterioles is seen in the distal esophagus.51 Dysphagia occurs as a result of impaired esophageal motility, and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is related to hypotensive LES pressures, impaired esophageal clearance of acid, and reduced acid-neutralizing capacity due to xerostomia with reduced saliva production.52 The incidence of esophagitis approaches 100% in patients with severe cutaneous involvement.53 The extent of hypomotility varies from occasional uncoordinated contractions to complete paralysis.54 The severity of esophageal dysmotility correlates with the development of interstitial lung disease.55,56 Stricture formation from GERD may contribute to dysphagia, affecting approximately 8% of patients.57 Upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage has been reported from esophageal ulcers, rare esophageoatrial fistulas, and esophageal telangiectasia.58,59 An increased risk of infectious esophagitis with Candida (see Chapter 45) has been attributed to esophageal dysmotility and concomitant immunosuppressive therapy.60 Severe esophagitis typically responds to proton pump inhibitors but may require higher doses for maximal effect.61 A neuropathic achalasia-like syndrome has also been reported.62 The prevalence of Barrett’s metaplasia of the esophagus in patients with PSS ranges between 7% and 38%.63,64 A recent cohort study reported an increased incidence of carcinoma of the tongue and esophagus in patients with PSS.65

Gastric involvement most commonly leads to gastroparesis but other manifestations may include dyspepsia, exacerbation of GERD, or gastric hemorrhage from gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE, watermelon stomach). Delayed gastric emptying has been shown using radionucleotide scintigraphy or radiopaque pellets, with cutaneous electrogastrography demonstrating bradygastria and decreased amplitude of electrical activity.56,66,67 Prokinetic agents such as metoclopramide and erythromycin may increase LES pressures and improve gastric emptying in some patients with PSS.57

The pathologic changes in the small bowel of PSS patients consist of smooth muscle atrophy and deposition of collagen in submucosal, muscular, and serosal layers. Small bowel hypomotility is present in as many as 88% of cases.68 In the early stages of the disease, hypomotility is caused by neuropathic involvement, which may be more responsive to prokinetic agents. In advanced cases, hypomotility is more likely a result of “myopathic” and “fibrotic” changes.57 The interdigestive migrating motor complex (IMMC) is frequently absent or markedly diminished in amplitude in PSS patients with symptoms of intestinal dysmotility.69 Small bowel radiographic abnormalities are present in about 60% of PSS patients, but they may not correlate with symptoms. The duodenum is often dilated, especially in its second and third portions, often with prolonged retention of barium.70 Typically the jejunum is dilated and foreshortened because of mural fibrosis, but valvulae conniventes of normal thickness give rise to an accordion-like appearance. Pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis, pseudo-obstruction, pseudodiverticula, sacculations, intussusception, acquired intestinal lymphangiectasia, and small bowel volvulus have been noted.71–73

Symptoms of small intestinal PSS include bloating, borborygmi, anorexia, nausea, and vomiting. Rarely, thrombosis of large mesenteric arteries with extensive bowel necrosis may occur.74 Malabsorption with steatorrhea is present in as many as a third of PSS patients68 and is caused by bacterial overgrowth (see Chapters 101 and 102). Although antibiotic therapy can be effective in these patients, d-xylose malabsorption is often incompletely reversed, suggesting that collagen deposition in PSS may also contribute to malabsorption.75 Although often disappointing, the use of prokinetic agents such as metoclopramide may be effective in some cases. Octreotide in low doses and erythromycin also may provide sustained relief from nausea, abdominal pain, and bloating in some patients with pseudo-obstruction.76

Delayed colonic transit and impaired anal sphincter function are frequently found in constipated patients with PSS.77,78 Cisapride (a drug no longer available in the United States) accelerates colonic transit,79 but refractory cases may require surgery.80 Colonic stricture, volvulus, and bleeding from mucosal telangiectasias have been reported.81,82 Wide-necked diverticula can be seen, especially in the antimesenteric border of the transverse and descending colons. Rectal prolapse worsens anal sphincter function, aggravating fecal incontinence in patients with PSS.83 Rectal bleeding can occur from vascular ectasia.84

Pancreatic exocrine secretion is depressed in a third of patients with PSS, and idiopathic calcific pancreatitis has been reported.85 In addition, arteritis resulting in ischemic pancreatic necrosis has been described in patients with PSS.86,87 Gallbladder motility is not altered in PSS.88

SYSTEMIC LUPUS ERYTHEMATOSUS

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a multisystem disease characterized by immune system abnormalities and the production of autoantibodies with tissue damage. Gastrointestinal symptoms are common in patients with active SLE. Oral ulcers (one of the criteria used to diagnose SLE) are most commonly seen in the buccal mucosa, hard palate, and vermilion border.89 In SLE, dysphagia (1% to 13% of patients) and GERD (11% to 50% of patients) poorly correlates with esophageal manometric abnormalities such as hypoperistalsis.90 Dysphagia is typically related to GERD or peptic stricture, with one report of esophageal epidermolysis bullosa acquisita.91 Malabsorption of d-xylose, steatorrhea, hyperplastic gastropathy, and protein-losing enteropathy have been described (see Chapter 28); the latter can be steroid responsive.92,93 Lupus peritonitis is a diagnosis that can be made only after other causes have been carefully excluded. Pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis may be an isolated benign condition or may accompany lupus vasculitis or necrotizing enterocolitis.94,95

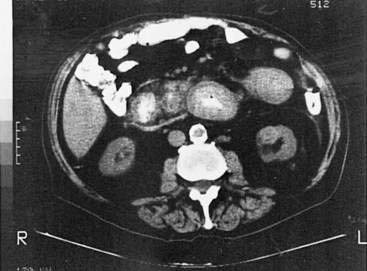

One of the most devastating complications of lupus is gastrointestinal vasculitis. Affecting only 2% of patients, it has a fatality rate of more than 50%.96 Common sequelae include ulceration, hemorrhage, perforation, and infarction.97–99 Pancreatitis,100,101 gastritis, hemorrhagic ileocolitis resembling inflammatory bowel disease, and intussusception also have been reported. Although occasional case reports have documented polyarteritis-like changes on visceral arteriograms (described later), the typical pathologic changes are seen in the small vessels of the bowel wall rather than the medium-sized vessels of the bowel wall.94 Computed tomography (CT) scan may help establish the diagnosis of ischemic bowel disease in SLE if there are at least three of the following five CT findings: (1) bowel wall thickening, (2) target sign (a thickened bowel wall with peripheral rim enhancement or an enhancing inner and outer rim with hypoattenuation in the center), (3) dilatation of intestinal segments, (4) engorgement of mesenteric vessels, and (5) increased attenuation of mesenteric fat.102 Because visceral angiography is not routinely helpful, the diagnosis is difficult to establish. The role of endoscopy or upper gastrointestinal series in the diagnosis of lupus vasculitis is not well defined. The diagnosis currently rests on clinical judgment, findings on CT scans, and occasionally from surgical specimens when exploratory laparotomy is undertaken to rule out acute surgical emergencies.103 Treatment of abdominal lupus-induced vasculitis with glucocorticoids has been largely unsatisfactory. Although a controlled clinical trial comparing cyclophosphamide with glucocorticoids has not been performed, anecdotal reports of dramatic responses to intravenous cyclophosphamide are promising.94 Some investigators have suggested that cyclophosphamide be considered early in patients who have not shown significant improvement shortly after high-dose glucocorticoids are started.

Patients with SLE have a 25% to 50% incidence of abnormal liver biochemical tests during the course of their disease, but clinically significant liver disease is rare.104 Abnormal liver tests are commonly associated either with medication use or with mild, predominantly lobular hepatitis associated with periods of SLE activity.104,105 Despite the shared association with antinuclear antibodies, the typical histologic and clinical features of autoimmune hepatitis are rarely observed in adult patients with SLE.104,106 Concurrent SLE and autoimmune hepatitis occur more frequently in pediatric patients.106 In addition, SLE patients with anticardiolipin antibodies or lupus anticoagulants may have thrombotic events in the liver leading to Budd-Chiari syndrome or nodular regenerative hyperplasia manifested by complications of portal hypertension.104,107

POLYMYOSITIS AND DERMATOMYOSITIS

Polymyositis is a syndrome characterized by weakness, high serum levels of striated muscle enzymes (creatine kinase, aldolase), and electromyographic (EMG) or biopsy evidence of an inflammatory myopathy. When accompanied by a characteristic violaceous rash on the extensor surfaces of the hands and periorbital regions, the disease is termed dermatomyositis. The primary gastrointestinal symptoms are due to involvement of the cricopharyngeus, resulting in nasal regurgitation, tracheal aspiration, and impaired deglutition.108 Involvement is not limited to skeletal muscle fibers. Disordered esophageal motility, impaired gastric emptying, and poorly coordinated small intestinal peristalsis have been noted.109 Malabsorption, malnutrition, and pseudo-obstruction rarely occur.110 Pathologically, edema of the bowel wall, muscle atrophy, fibrosis, and mucosal ulcerations or perforation due to vasculitis may be seen at any level of the gut. Symptoms include heartburn, bloating, constipation, and gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Pneumoperitoneum, pneumatosis intestinalis, colonic dilation, and pseudodiverticula also may be seen. Perforations of the esophagus and of duodenal diverticula have been described as rare complications.111,112

In middle-aged to older adult patients, dermatomyositis and possibly polmyositis are associated with an increased prevalence of malignancy.113 The possibility that gastrointestinal symptoms may be the resultl of an underlying malignancy should be considered when evaluating these patients (see Chapter 22).

MIXED CONNECTIVE TISSUE DISEASE

Mixed connective tissue disease (MCTD) is a syndrome with overlapping features of PSS, polymyositis, and SLE, often in the presence of high levels of antibody directed against ribonucleoprotein. Upper gastrointestinal symptoms are seen in most patients.114 Abnormalities include diminished esophageal peristalsis (48%), esophageal stricture (6%), abnormal gastric emptying (6%), and gastric bezoar (2%).114 Small intestinal and colonic involvement includes dilation of proximal bowel, slow transit, intestinal pseudo-obstruction, diverticulosis, and, rarely, intestinal vasculitis. Pancreatitis also has been reported.114 Unlike PSS, the esophageal motility disturbances seen in MCTD appear to improve with the administration of glucocorticoids.

SJÖGREN’S SYNDROME

Sjögren’s syndrome (SS), occurring alone (primary SS) or in association with systemic autoimmune rheumatic diseases (secondary SS), is characterized by lymphocytic tissue infiltration of lacrimal and salivary glands with the clinical findings of keratoconjunctivitis sicca and xerostomia. As reviewed in Chapter 22, excessive dryness of the mouth and pharynx leads to oral symptoms of soreness, adherence of food to buccal surfaces, fissuring of the tongue, and periodontal disease.115 Dysphagia, reported by up to three quarters of patients with SS, can result from esophageal dysmotility and a lack of saliva; however, symptoms do not correlate with manometry or salivary secretion.116–118 Mild atrophic antral gastritis can be seen in 25% of patients with primary SS, but 31% were infected with H. pylori.119 Older studies that reported higher rates and greater severity of gastritis did not control for H. pylori infection. GAVE can occur in patients with SS and is responsive to fulguration therapy.120 A triad of sclerosing cholangitis, chronic pancreatitis, and SS has been reported in eight patients.121 Pancreatic exocrine function is frequently impaired.122 In primary SS, 7% of patients have positive antimitochondrial antibodies and among patients with primary biliary cirrhosis, clinical manifestations of SS are common (see Chapter 89).115

POLYARTERITIS NODOSA AND OTHER VASCULITIDES

Polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) is a necrotizing vasculitis of small and medium-sized muscular arteries, frequently with visceral involvement (Fig. 35-1). A characteristic feature of this condition is the finding of aneurysmal dilatations up to 1 cm in size seen on visceral angiography (Fig. 35-2). Abdominal complications occur in up to 50% of patients and carries a poor prognosis.123 Other clinical features of PAN include fever, myalgia, arthralgia of the large joints, mononeuritis multiplex, and livedo reticularis. Mesenteric visceral arteriograms are abnormal in up to 80% of patients with gastrointestinal involvement, with the superior mesenteric artery most commonly involved.123 Organ damage resulting from ischemia frequently underlies symptoms. The most common gastrointestinal manifestation is abdominal pain with other common symptoms including nausea, vomiting, and gastrointestinal bleeding.123 Bowel infarction and perforation, aneurysmal rupture, and acute cholecystitis are common causes of acute abdomen in PAN.123 Rarely, PAN can present as acalculous cholecystitis secondary to isolated vasculitis of the gallbladder.124 Pancreatitis,125 appendicitis,126 hemobilia,127 solitary biliary strictures,128 and hepatic infarcts129 also have been reported to complicate PAN. The frequency of hepatitis B infection in PAN has declined from more than 30% to less than 10% because of improved screening of the blood supply and vaccination against hepatitis B.130 Because of the frequent association with hepatitis B infection and potential association with hepatitis C infection (see Chapters 78 and 79), patients with clinical manifestations of PAN should be assessed for evidence of hepatitis B or C infection.

Churg-Strauss syndrome (CSS, allergic granulomatous angiitis) is a small to medium-sized vessel vasculitis characteristically associated with eosinophilia, asthma, sinusitis, and rhinitis. Abdominal pain is the most common gastrointestinal symptom.131 Preceding the vasculitic phase of CSS, patients may present with an eosinophilic gastroenteritis associated with abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and bleeding with an absolute eosinophil count of greater than 1500 cells/mm3 (see Chapter 27).132 Additional gastrointestinal manifestations of CSS include pancreatitis, cholecystitis, ascites, small intestinal ulcerations, and perforation.131,133,134 Colonic involvement may present with multiple ulcers or obstruction.134,135

Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP) is a systemic vasculitis characterized by nonthrombocytopenic purpura, arthralgias, renal disease, and colicky abdominal pain. Although the disease is frequently seen in children and adolescents, adults of any age may be affected. Colicky abdominal pain and gastrointestinal bleeding are seen in two thirds of cases.136 Colonoscopic and endoscopic findings in bleeding patients include erosive duodenitis, small aphthous ulcerations, and petechial colonic lesions.137 In patients who undergo CT scan, common findings include bowel-wall thickening, dilated intestinal segments, mesenteric vascular engorgement, and regional lymphadenopathy.138 Other reported gastrointestinal complications of HSP include protein-losing enteropathy, esophageal and ileal structures, gastric and small bowel perforations, bowel infarction, pancreatitis, appendicitis, cholecystitis, intramural hematomas, and intussusception.139

Malignant atrophic papulosis (Kohlmeier-Degos disease) is a rare vasculitis that causes nausea, vomiting, bleeding, malabsorption, bowel ischemia, and perforation.140 Scattered on the skin are red papules that become hypopigmented atrophic scars (see Fig. 22-13).

Cogan’s syndrome is characterized by nonsyphilitic interstitial keratitis, audiovestibular symptoms, and large-vessel vasculitis that may involve the gut. Gastrointestinal manifestations include abdominal pain, diarrhea, hepatomegaly, and splenomegaly.141 Crohn’s disease has been reported in association with this rare condition.142

Wegener’s granulomatosis, a systemic vasculitis characterized by pulmonary, sinus, and renal involvement, less commonly affects the gut.143 Inflammatory ileocolitis with hemorrhage, gangrenous cholecystitis, and bowel infarction have been reported.144 Wegener’s granulomatosis may mimic Crohn’s disease with granulomatous gastritis or ileitis.145,146

Mixed immunoglobulin (IgG-IgM) cryoglobulinemia characterized by the triad of purpura, arthralgia, and asthenia may complicate chronic hepatitis C infection (see Chapter 79) and a variety of immune diseases, including inflammatory bowel disease, celiac disease, and postintestinal bypass syndrome. Cryoglobulinemia may cause severe visceral vasculitis with diarrhea, ischemia, and perforation of the small or large intestine.147

BEHÇET’S DISEASE

Behçet’s disease is an idiopathic inflammatory disorder characterized by oral aphthous ulcers, genital ulcers, uveitis, and skin lesions, with gastrointestinal involvement occurring in up to 50% of patients.148 As in Crohn’s disease, ulceration may occur throughout the alimentary tract, with the ileocecal region most commonly affected. Differentiating Behçet’s from Crohn’s disease can be difficult because of similarities in gastrointestinal symptoms, endoscopic findings, histology, and extraintestinal manifestations. Involvement of the esophagus includes ulcers (Fig. 35-3), varices, and perforation.149 In the stomach, which is infrequently involved, aphthous ulcers may be seen. The typical intestinal involvement in Behçet’s disease includes “punched-out” ileocecal ulcerations, the most common finding on colonoscopy. Additional manifestations of Behçet’s disease include abdominal pain, diarrhea, bleeding, perforation, and fistulas (perianal, rectovaginal, and enteroenteric).150 Hepatic or portal vein thrombosis may occur in patients with Behçet’s, and this syndrome should be included in the differential diagnosis of patients presenting with Budd-Chiari syndrome.151,152 Medical therapy of the gastrointestinal lesions of Behçet’s disease includes mesalamine, glucocorticoids, immunomodulators such as azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine, infliximab, and thalidomide.153,154 Surgical intervention is associated with a high rate of recurrence, with nearly 50% requiring repeat surgery.155

SERONEGATIVE SPONDYLOARTHROPATHIES (REACTIVE ARTHRITIDES)

The term seronegative spondyloarthropathy is used to describe an interrelated group of inflammatory disorders that include ankylosing spondylitis, reactive arthritis (formerly called Reiter’s syndrome), and psoriatic arthritis. The term has also been used to describe the enteropathic spondylitis associated with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis.156 These disorders are characterized by the absence of rheumatoid factor, an association with human leukocyte antigen-B27 (HLA-B27), and inflammation at the site of bony insertion of ligaments and tendons (enthesitis). There is a high prevalence of clinically silent inflammatory colon lesions in patients with these seronegative spondyloarthropathies.157 Capsule endoscopy may yield more small bowel abnormalities than ileocolonoscopy.158 Conversely, 22% of patients with inflammatory bowel disease have evidence of a seronegative spondyloarthropathy, with ankylosing spondylitis most commonly seen.159 Although infliximab has been shown to induce remissions in some patients with ankylosing spondylitis as well as in Crohn’s disease, the effect of infliximab on gastrointestinal inflammatory lesions in typical seronegative spondyloarthropathies has not yet been studied.

MARFAN’S AND EHLERS-DANLOS SYNDROMES

Owing to defective collagen synthesis, patients with Marfan’s or Ehlers-Danlos syndrome develop skin fragility, megaesophagus, small intestine hypomotility, giant jejunal diverticula, bacterial overgrowth, and megacolon.160 Mesenteric arterial rupture and intestinal perforation also can occur.161

FAMILIAL MEDITERRANEAN FEVER

Familial Mediterranean fever (FMF) is an autosomal recessive inherited disease characterized by recurrent self-limiting attacks of fever, joint pain, and abdominal pain. Acute attacks typically last three to five days. FMF is most commonly seen in people of Mediterranean origin including Sephardic Jews, Arabs, Turks, Greeks, Italians, and Armenians, although FMF has been described in Cubans, and Belgians. The gene responsible for FMF in Mediterranean patients, designated MEFV, has been mapped to chromosome 16, which encodes a 781-amino acid protein called pyrin or marenostrin.162

Gastrointestinal symptoms, typically manifest as episodic abdominal pain, are seen in 95% of patients, and this may be the presenting symptom in as many as 50% of cases.163 Abdominal pain may be diffuse or localized and may range from mild bloating to acute peritonitis with boardlike rigidity, rebound tenderness, and air-fluid levels on upright radiographs. The acute presentation may be confused with acute appendicitis, cholecystitis, or pelvic inflammatory disease, whereas relapsing and remitting attacks may be confused with other diseases such as porphyrias. Small bowel obstruction from adhesions may occur as a consequence of recurrent sterile peritonitis or as a result of previous exploratory surgery. In patients with obstruction due to adhesions, abdominal attacks without other typical symptoms (arthralgias, fever) should tip off the clinician to consider an obstruction.164 The diagnosis of FMF is based on validated clinical criteria including fever, serositis, location of pain, and response to colchicine.165

In FMF, the long-term prognosis is poor in patients who develop nephrotic syndrome and chronic kidney disease from amyloid A deposition163 (amyloidosis is discussed later in this chapter). Prophylactic colchicine has been shown to reduce the frequency of attacks, prevent amyloidosis, and avoid renal failure.166 Vasculitis in the form of HSP, PAN, protracted febrile myalgia, or Behçet’s is encountered in 3% of FMF patients.163

ONCOLOGIC AND HEMATOLOGIC DISEASES

METASTASES

Metastasis to the gut can occur by direct invasion from adjacent organs, by intraperitoneal seeding, or by hematogenous or lymphatic spread. About 20% of all patients with nongastrointestinal malignancies have metastases to the gastrointestinal tract, the most common of which are breast, lung, and ovarian cancers and melanoma (Fig. 35-4).167 Patterns of metastases are not random but reflect the location and histologic type of the primary tumor. The esophagus is most frequently affected by direct extension from tumors arising from adjacent structures (bronchus and stomach). The stomach is a particularly common site of breast cancer metastases, and the small intestine can be involved by tumor extension from the stomach, pancreas, biliary system, kidney, or retroperitoneum. The pancreas is usually an asymptomatic site of metastasis, with the most common primary tumors being lung, gastrointestinal, and renal.168 The ileum may be affected by cancers arising in the colon or pelvis. Metastases to the gut typically begin in the serosa or submucosa and produce intraluminal lesions that can lead to obstruction, submucosal polypoid masses that can result in intussusception or ulcerated mucosal lesions. The most common presenting clinical condition in patients with metastatic lesions to the gut is small bowel obstruction. Lobular breast cancer, malignant melanoma, and non–small cell lung cancer are the most common neoplasms to cause small bowel obstruction from isolated metastases.169 In addition, pain, fever, ascites, gastrointestinal bleeding, and perforation have been described.

Metastases to the gastrointestinal tract may be difficult to diagnose. Barium contrast studies may reveal extramural masses, mucosal ulcerations, or a rigid stomach with the appearance of linitis plastica. CT may be helpful in determining the primary tumor, in tumor staging, and in detecting large serosal implants. Small bowel metastases, however, are detectable radiographically in only 50% of cases.170

When feasible, surgical resection should be used to treat gastrointestinal metastases that result in obstruction, perforation, or significant hemorrhage. If a solitary bowel metastasis is the only evident site of disseminated malignancy, segmental bowel resection should be performed, offering a small chance for cure. In aggressive resections of melanoma metastases, the mesenteric nodes draining the involved segment of bowel should be resected because they frequently contain tumors.171

PARANEOPLASTIC SYNDROMES

Paraneoplastic syndromes affecting the gut include the hormonal effects of carcinoid tumors, vasoactive intestinal polypeptide-secreting tumors (VIPomas), gastrinomas, and somatostatinomas (see Chapters 31 and 32), as well as the gastrointestinal effects of hypercalcemia (constipation, nausea, and vomiting). A watery diarrhea syndrome with elevated serum immunoreactive VIP has been described accompanying nonpancreatic tumors such as bronchogenic carcinomas, ganglioneuromas, pheochromocytomas, and a rare mastocytoma.172 Elevated serum levels of somatostatin, calcitonin, gastrin, and corticotropin also have been reported in pheochromocytoma.173

Paraneoplastic gastrointestinal dysmotility may occur in some patients with occult or established malignancy and specific serum antibodies. Clinically the patient may present with pseudoachalasia, gastroparesis, intestinal pseudo-obstruction, or constipation. Intestinal pseudo-obstruction (see Chapter 120) is most frequently associated with small cell carcinoma of the lung but has been described with other tumors such as squamous cell lung carcinoma, lymphoma, melanoma, and cancers of the kidney, breast, and prostate.174–176 Patients with paraneoplastic intestinal pseudo-obstruction characteristically suffer from constipation and obstipation and from symptoms of intestinal obstruction. In addition, dysphagia, gastroparesis, early satiety, autonomic insufficiency, and peripheral neuropathy have been described.177 The onset of symptoms may precede the discovery of the primary tumor by several years. The gastrointestinal pathology in this syndrome is confined to the myenteric plexus, in which an inflammatory lymphocytic infiltrate is variably seen accompanying neuronal degeneration.178 Cross-reacting autoantibodies found in the sera of these patients bind to the primary tumor cells and to neural cells in the myenteric plexus, resulting in inflammation and destruction of the myenteric plexus.179 In the setting of pseudo-obstruction, detection in the serum of circulating antineuronal nuclear antibodies (ANNA-1 or anti-Hu), type 1 Purkinje cell antibodies (PCA-1), or N-type calcium channel binding antibodies should suggest a paraneoplastic process and prompt further evaluation for an underlying malignancy.177 ANNA-1 are postulated to induce neuronal apoptosis leading to gut dysmotility.180 Although the symptoms of paraneoplastic pseudo-obstruction may resolve with successful treatment of the primary tumor, persistence of gastrointestinal symptoms despite effective anticancer treatment is more common. Attempts to alleviate the symptoms of pseudo-obstruction with prokinetic agents have been disappointing.

HEMATOLOGIC MALIGNANCIES

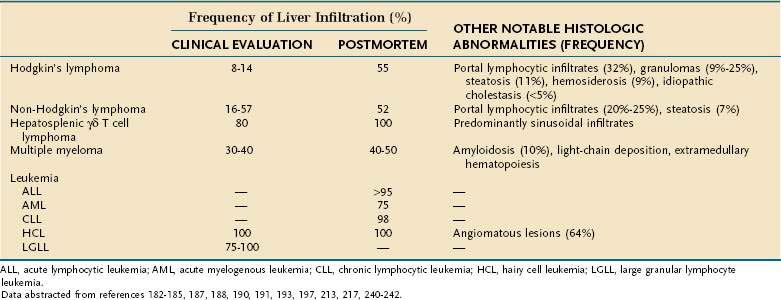

Liver involvement during hematologic malignancies is only rarely life threatening or a source of great morbidity. Nevertheless, the liver is a major component of the reticuloendothelial system, and thus it is not surprising that malignant infiltration of the liver commonly occurs in such diseases.181 As detailed in Table 35-2, the frequency of malignant infiltration varies from less than 10% to nearly 100% depending on the nature of the underlying hematologic malignancy. In addition to histologic and biochemical abnormalities related to malignant infiltration, a variety of other hepatic abnormalities are observed in a significant fraction of such patients. Many of these abnormalities are related to toxicity of pharmacologic or radiation therapies or to the secondary opportunistic or transfusion-related infections commonly observed in such patients. In addition, a variety of nonspecific histologic abnormalities of uncertain etiology such as steatosis, fibrosis, hemosiderosis, and nonspecific portal lymphocytic infiltrates are observed commonly in treated as well as untreated patients. Other hepatic manifestations relatively unique to selected malignancies also may occur. Such notable paraneoplastic manifestations include granuloma formation or development of pronounced intrahepatic cholestasis in patients with Hodgkin’s disease and deposition of amyloid in patients with multiple myeloma.

Hodgkin’s Lymphoma (see Chapter 29)

As detailed in Table 35-2, malignant infiltration of the liver is observed in only a minority of patients with untreated Hodgkin’s disease.182,183 However, autopsy series have noted hepatic involvement in as many as 55% of patients,184 suggesting that hepatic involvement increases with disease progression. Although Reed-Sternberg cells have been reported in only 8% of liver biopsies at the time of initial evaluation, fully a third of specimens exhibit nonspecific mononuclear cell infiltrates in portal tracts and approximately 10% to 25% have noncaseating hepatic granulomas not associated with malignant histiocytes or infectious etiologies.182,185 Moderate elevations of serum alkaline phosphatase activity are often observed, especially in febrile patients or patients with advanced stage disease.186 Although such elevations almost invariably appear related to elevations of the hepatic fraction of serum alkaline phosphatase activity,186 not all patients with elevated alkaline phosphatase levels are found to have tumor infiltration of the liver.182,186 All patients with hepatic involvement have been reported to have splenic involvement,182 but again the presence of splenic infiltration does not invariably imply liver involvement.

Although Hodgkin’s disease may involve extrahepatic bile ducts or lymph nodes in the porta hepatis and cause extrahepatic obstruction, multiple reports describe an additional syndrome of idiopathic intrahepatic cholestasis unrelated to hepatic infiltration, extrahepatic obstruction, or other identifiable causes.187–189 The degree of cholestasis is often disproportionate to apparent tumor load.187,189 However, cholestasis has been reported to resolve with response to systemic therapy,187 although in other cases this syndrome has been associated with intractable, fatal liver damage. Recently, progressive loss of small intrahepatic bile ducts has been documented in some of these patients,189 suggesting that this syndrome may be caused by destruction of bile duct epithelial cells either by direct effects of tumor cells invading the intrahepatic bile ducts or by indirect effects of cytokines released from lymphoma cells.

As liver involvement with Hodgkin’s disease defines a patient as having stage IIIE or IV disease, correct interpretation of causes of abnormal liver biochemistries in patients with this disease is often of significant importance in determining prognosis and therapy. Numerous studies have noted the superiority of laparotomy or peritoneoscopy to blind percutaneous liver biopsy in detecting hepatic involvement with Hodgkin’s disease. Presumably this relates to the relatively small volume of tissue obtained at percutaneous liver biopsy and the difficulty in finding diagnostic Reed-Sternberg cells in the liver. Laparoscopy provides a diagnostic yield equal to that obtained at laparotomy, and laparoscopy with or without laparoscopic splenectomy has become the standard approach to diagnostic staging in the majority of patients.183,190

Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma (see Chapter 29)

Lymphoma involves the gastrointestinal tract either as the primary site or secondarily from systemic lymphomas. Lymphomas may affect any organ and must be included in the differential diagnosis of any gastrointestinal symptom, especially in patients with advanced acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. As noted in Table 35-2, the frequency of liver involvement at initial clinical staging is significantly higher in patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas than in those with Hodgkin’s disease. When evaluated by percutaneous liver biopsy, 16% to 26% of patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas are found to have liver infiltration191 with significantly higher percentages found to have hepatic involvement when evaluated by laparoscopy.192 In both Hodgkin’s and non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas, the majority of infiltrative lesions are portal in location.193 Although the overall frequency of hepatic involvement appears similar in different histologic types of lymphoma,191 primary hepatic lymphoma is an unusual variant that occurs more often in diffuse large cell lymphomas of B cell origin than in T cell or non–B, non–T cell lymphomas.194,195 In contrast to secondary lymphomatous involvement of the liver that is often only detected by histologic evaluation, patients with primary lymphoma are commonly found to have evidence of mass lesions on CT, magnetic resonance imaging, or other hepatic imaging procedures that may mimic primary or metastatic carcinoma.194–196 Some reports have suggested an association between primary hepatic lymphomas and immunosuppression or chronic viral hepatitis, but such comorbid conditions are noted in only a minority of cases.194,195

Recently, hepatosplenic γδT cell lymphoma has been recognized as a distinct lymphoma entity.197 This extremely rare form of lymphoma occurs most frequently in young males who present with hepatosplenomegaly secondary to diffuse hepatic sinusoidal and splenic sinus infiltration with clonal populations of T cell receptors, gamma delta (γδTCR) expressing cells. Lymphadenopathy is absent, but bone marrow involvement common at the time of presentation and cytogenetic analysis commonly reveals an isochromosome 7q and trisomy 8.19

The most common liver test abnormality reported in patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma is a moderately elevated serum alkaline phosphatase. Overall liver test abnormalities are poorly predictive of the presence or absence of lymphomatous infiltration of the liver.192 This likely relates in part to the presence of a variety of nonspecific histologic abnormalities191,193 including portal lymphocytic infiltrates, hemosiderosis, and steatosis that may be associated with liver test abnormalities in patients without hepatic involvement. Other patients with lymphomatous liver infiltrates may have normal liver tests.

Noncaseating granulomas also have been found in the portal tracts of patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma though at a much lower frequency than observed in Hodgkin’s disease.198 Extrahepatic obstruction secondary to nodal involvement in the porta hepatis also may occur,192 and in some cases bile duct involvement may mimic the features of cholangiocarcinoma.199 Percutaneous liver biopsies have been found to be of value in detecting hepatic involvement with lymphoma, and if such specimens are properly processed, immunotyping can be performed to better characterize the phenotype of the malignant cells.200 However, quantity of tissue obtained appears very important in determining diagnostic sensitivity, with biopsy at laparotomy being superior to either blind percutaneous or laparoscopic biopsies in obtaining a diagnosis of hepatic infiltration by non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.192

Leukemia

Approximately 10% of patients with leukemia suffer significant gastrointestinal complications, either from the leukemia itself or as the result of chemotherapy (Table 35-3).201 Examination of autopsy specimens reveals gastrointestinal involvement in less than 15% of all patients with leukemia.202 Acute myelogenous leukemia is the type most likely to affect the gut. Lesions result from four major causes: leukemia cell infiltration, immunodeficiency, coagulation disorders, and drug toxicities. Radiologically, leukemic lesions assume many forms. Infiltration of the bowel may produce polypoid masses (chloromas), plaquelike thickenings, ulcers, and diffuse masses. Esophageal filling defects with clot and debris have been described.203 Gastric mucosal folds can assume a “brainlike” deeply convoluted appearance resembling adenocarcinoma. Diffuse intestinal leukemoid polyposis may produce obstruction, hemorrhage, or intussusception.

| Leukemic Invasion of the Bowel and Related Structures |

BMT, bone marrow transplantation; CMV, cytomegalovirus; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; HSV, herpes simplex virus; SOS, sinusoidal obstruction syndrome.

Immunodeficiency and immunocytopenia may lead to agranulocytic ulcers with bacterial invasion and bleeding. Coagulation defects can produce intramural hematomas and hemorrhagic necrosis of the bowel. Clinical syndromes are myriad. Common oral symptoms (see Chapter 22) are gingival bleeding, hypertrophy, inflammation, and focal ulcerations. Oral mucositis (stomatitis) is a severe inflammatory condition seen in the setting of recent chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or bone marrow transplantation. Treatment consists of appropriate antifungal, antiviral, or antibacterial therapy as well as viscous lidocaine and systemic analgesia. Esophageal lesions, usually caused by candidiasis or herpesviruses, may cause odynophagia, dysphagia, or bleeding (see Chapter 45). Gastric acid hypersecretion with peptic ulcers has been reported in a patient with hyperhistaminemia secondary to basophilic granulocytic leukemia.204 Massive gastrointestinal hemorrhage may result from infectious lesions, agranulocytic ulcers, or primary leukemic lesions of the gastrointestinal tract. The treatment of bleeding gastric and colonic leukemic lesions with radiation therapy has occasionally met with success and has been advocated by some investigators.205

A dire complication, seen in 5% of patients with acute leukemia and 3% of those with chronic leukemia, is the development of an acute abdomen. Acute appendicitis, abdominal abscesses, and perforation are noted with increased frequency. Necrotizing ileocecal enterocolitis and leukemic typhlitis are relatively infrequent but life-threatening problems in neutropenic leukemia patients. Typhlitis (i.e., inflammation of the cecum) complicates 6.5% of cases of acute myeloid leukemia and 4.6% of cases of acute lymphoblastic leukemia.206 Typhlitis typically manifests after induction chemotherapy and is usually preceded by neutropenia.207 Rarely, typhlitis can be the presenting manifestation of acute leukemia.208 Although the cause of this condition is not entirely clear, multiple factors such as chemotherapy, radiotherapy, neutropenia, and altered gastrointestinal flora are implicated in its pathogenesis.207 Cecal superinfection with fungi and with cytomegalovirus also has been associated with typhlitis. Patients usually present with fever, severe right lower quadrant pain, and occasionally an acute abdomen. Bloody diarrhea accompanies typhlitis in 35% of patients.209 The diagnosis can be inferred indirectly by the finding of symmetrical cecal thickening on abdominal ultrasonography or CT.207 Bowel wall thickness greater than 10 mm is associated with a 60% mortality.210 Most patients with leukemic typhlitis can be managed conservatively with the administration of intravenous fluids, packed red blood cells, and, as needed, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), platelets, and broad-spectrum antibiotics. On rare occasions surgery may be required if dire complications arise.

Pseudomembranous colitis may complicate leukemia even in the absence of antibiotic therapy.211 Other rare complications are listed in Table 35-3. Proctologic problems can include stercoral ulcers, neutropenic ulcers, and perirectal abscesses (see Chapter 125).

At initial presentation, hepatomegaly is present in the majority of patients with acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL) and in a significant minority of patients with acute myelogenous leukemia (AML). In patients with advanced stages of these acute leukemias, incidence of liver involvement has been reported in more than 95% of cases of ALL and in about three quarters of patients with AML at autopsy.212 The hemorrhagic complications of these acute leukemias rarely permit histologic evaluation of the liver in patients with early, active disease. Therefore, it is difficult to discern the relative contributions of leukemic infiltrates, extramedullary hematopoiesis, other infectious or toxic complications of these diseases, or the therapies employed to the development of hepatomegaly and/or liver test abnormalities.

In patients with leukemias that run more chronic courses, sufficient numbers of patients have been biopsied to indicate that hepatic involvement is far more commonly detected on histologic evaluation than initially indicated by clinical or laboratory assessment.213–217 In an autopsy series, 98% of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) were found to have leukemic infiltration consisting predominantly of portal infiltrates that usually left the hepatic limiting plates intact.213 However, in some cases, leukemic infiltrates were observed to bridge adjacent portal tracts and were associated with hepatocellular necrosis, bridging necrosis and occasionally pseudolobule formation. In contrast to the predominantly portal pattern of hepatic infiltration during CLL, liver involvement during hairy cell leukemia (HCL), large granular lymphocyte leukemia (LGLL), or the adult T cell leukemia/lymphoma syndrome associated with human T-lymphotropic virus type 1 (HTLV-1) infection is usually characterized by diffuse sinusoidal infiltration or a mixed pattern of portal and sinusoidal involvement.214–217 As in the case of CLL, all or nearly all patients with HCL including some without hepatomegaly or liver test abnormalities demonstrate hepatic infiltration on histologic evaluation.215,216 Although infiltration by HCL occasionally may be missed on conventional histologic evaluation, use of tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase staining215 and immunotyping by staining with monoclonal antibodies against lymphocyte cell surface markers200 has been reported to enhance diagnostic sensitivity and specificity. HCL has also been associated with angiomatous lesions in the liver created by disruption of the sinusoidal wall, creation of wide areas of communication between the sinusoidal lumen and space of Disse, and replacement of the sinusoidal cell lining by tumor cells in direct contact with hepatocytes.216

SYSTEMIC MASTOCYTOSIS

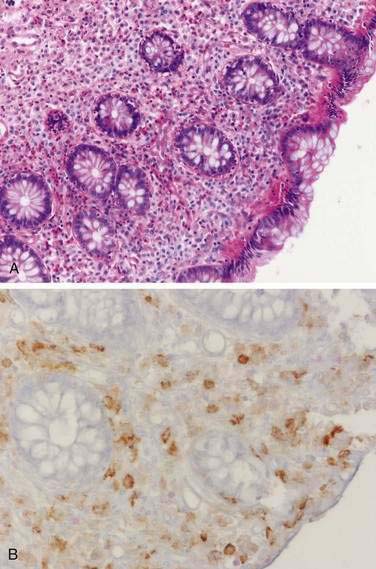

Systemic mastocytosis, a clonal disorder of the mast cell–progenitor associated with activating mutations in the c-kit gene, is characterized by a dense infiltrate of mast cells in extracutaneous tissue (bone marrow, spleen, liver, lymph nodes, and gastrointestinal tract) (Fig. 35-5).218 The classic dermatologic finding of urticaria pigmentosa may be seen with or without systemic involvement (see Chapter 22). The typical symptoms of mastocytosis (pruritus, flushing, tachycardia, asthma, headache) are believed to result from the release of histamine and prostaglandins (e.g., PGD2) from mast cells.219 Heparin is also released from mast cells and may contribute to a bleeding diathesis.220 Eighty percent of patients have gastrointestinal symptoms that include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain.221 Hepatomegaly, portal hypertension, splenomegaly, and ascites may occur frequently.222 These symptoms can be precipitated or provoked by heat, alcohol, aspirin, anticholinergics, NSAIDs, and contrast media.219 Hyperhistaminemia produces gastric hypersecretion in more than 40% of cases,223 and secretion may be as marked as in Zollinger-Ellison syndrome.224 Gastric hyperacidity correlates with the degree of histaminemia and with the presence of acid-peptic disease.223,224 Duodenal ulceration or duodenitis has been reported in more than 40% of cases.223 Gastrointestinal hemorrhage from peptic ulcers and from bleeding esophageal varices has been reported.224,225 Diarrhea has been reported in as many as 60% of cases, and minimal fat malabsorption occurs in some cases.220,223 Decreased absorption of d-xylose and vitamin B12 is also found in patients with mastocytosis.223 The cause of diarrhea is unclear. Some diarrheal symptoms (but not malabsorption) respond to H2-receptor antagonists, but there is no clear correlation between stool output and the degree of plasma histaminemia or gastric acidity.223 It is presumed that diarrhea and malabsorption are the result of morphologic changes in the absorptive mucosa. Jejunal biopsy specimens may show large numbers of mast cells in the lamina propria, muscularis mucosa, and submucosa, with normal villi or mild villous atrophy.226 The colon may also be involved (see Fig. 35-5). Endoscopy may reveal urticaria-like mucosal lesions, thickened gastric folds, and edematous mucosa, whereas colonoscopy has shown purple pigmented lesions.227 Small bowel radiographic abnormalities include bull’s-eye lesions resembling metastases, edema, thickened folds, and a nodular mucosal pattern.228 Abdominal ultrasound and CT may show hepatosplenomegaly, adenopathy, thickening of the omentum and the mesentery, and ascites.229 H1-receptor and H2-receptor antagonists, anticholinergics, oral disodium cromoglycate, and glucocorticoids have been used successfully to relieve the diarrhea and abdominal pain of mastocytosis.219 Imatinib mesylate, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, is not effective in systemic mastocytosis because a conformational change associated with the most common mutation (Asp816Val) interferes with drug binding.218

MYELOPROLIFERATIVE AND MYELOPHTHISIC DISORDERS

Because the liver is a major site of extramedullary hematopoiesis, hepatomegaly or mild liver test abnormalities secondary to extramedullary hematopoiesis may be appreciated in any of a variety of myeloproliferative disorders or marrow infiltrating malignancies. Benign or malignant proliferations of histiocytes (macrophages) or dendritic cells may be complicated by hepatomegaly or jaundice related to diffuse infiltration of hepatic sinusoids by erythrophagocytic histiocytes, development of peliosis hepatis or intrahepatic, or extrahepatic invasion of bile ducts and portal tracts by histiocytes or Langerhans’ (dendritic) cells.230–232 Erythrophagocytosis may be a manifestation of malignant histiocytosis or represent a reactive benign histiocyte proliferation in patients with advanced T cell lymphomas.197 Thus assessment of involved tissues for malignant cells of T cell or more rarely B cell origin should also be included in the diagnostic evaluation of cases of uncertain origin. Liver biopsies are commonly abnormal in untreated patients with Langerhans cell histiocytosis (formerly termed histiocytosis X). The most common abnormality is mild mononuclear cell infiltration of the portal tracts.231 However, portal triaditis associated with periportal fibrosis, cirrhosis, or extrahepatic cholangiographic evidence of sclerosing cholangitis also may be seen and in some patients may lead to severe cholestatic liver disease.231,232

Primary myelofibrosis (PMF) is a myeloproliferative disease characterized by bone marrow fibrosis with progressive anemia and splenomegaly. Portal hypertension, which occurs in 7% of patients with PMF, results from increased portal venous flow and from infiltration of the liver by foci of extramedullary hematopoiesis.233 Massive gastrointestinal hemorrhage complicates 5% of cases and most often is due to bleeding esophageal varices. Extramedullary hematopoiesis can involve the esophagus, stomach, and small bowel leading to abdominal pain and hemorrhage.234 Increased thrombotic complications have been associated with PMF, polycythemia vera, and essential thrombocytosis.235 Splenic infarction can cause left upper quadrant abdominal pain. As many as 50% of patients with hepatic vein thrombosis, or the Budd-Chiari syndrome, have an overt myelodysplastic syndrome.236 One study237 suggests that 80% of patients with hepatic vein thrombosis may have latent myeloproliferative abnormalities without overt disease (see Chapter 83).

DYSPROTEINEMIAS

Multiple myeloma or plasma cell tumors may directly involve the gastrointestinal tract with amyloidosis or with local infiltration by plasmacytomas. Twenty-one percent of patients with amyloidosis have multiple myeloma.238 As with gastrointestinal involvement by amyloidosis from other causes (see later), bowel wall infiltration and dysmotility underlie most clinical symptoms. Primary extramedullary plasmacytoma account for 3% to 5% of all plasma cell dyscrasias with gut involvement noted from the oral cavity to anus with manifestations including dysphagia, hemorrhage, pseudo-obstruction, and polyposis.239 Hepatomegaly and abnormalities of liver biochemistries are commonly observed in patients with multiple myeloma.240 In up to half of patients with hepatic histologic evaluation, either diffuse sinusoidal or portal infiltration or, less commonly, nodule formation in the liver by malignant plasma cells has been observed.193,240,241 The frequency of jaundice has ranged from 0% to 30% in series of patients with hepatic infiltration by multiple myeloma.240,241 Ascites formation or, more rarely, esophageal varices have been reported to complicate the course of 10% to 35% of patients with massive hepatic infiltration.200,240 Portal hypertension secondary to tumor infiltration appears to be the cause in most patients, although other causes including congestive heart failure, dissemination of myeloma cells into the peritoneal cavity or development of tuberculous peritonitis also have been noted. In addition to direct malignant infiltration and development of such nonspecific hepatic abnormalities as hemosiderosis or portal lymphocytic infiltrates, multiple myeloma is complicated in about 10% of patients by deposition of amyloid or non–amyloid-containing IgG light chain deposits in the space of Disse.200,240–242 Extramedullary hematopoiesis also may contribute to hepatomegaly or liver test abnormalities in these patients.240 Clinical staging and follow-up of patients with multiple myeloma are largely based on assessment of marrow, osseous, and serum or urinary abnormalities, and thus histologic evaluation of the liver is only occasionally considered. As discussed in the section dealing with amyloidosis later in this chapter, potential diagnostic benefits of liver biopsy must be weighed against concerns regarding bleeding complications.

Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia, a neoplasm characterized by malignant proliferation of lymphocytes producing IgM, presents with hepatomegaly or splenomegaly in one third of patients.243 Gastrointestinal IgM deposition may occur in an infiltrative pattern characterized by diffuse infiltration of the bowel wall with neoplastic cells similar to the pattern seen in immunoproliferative diseases. More commonly, acellular macroglobulin is deposited predominantly in the tips of the villi, the interstitium, and the lacteals, leading to lymphangiectasia.244 Small intestinal mucosal IgM deposits may stain weakly with periodic acid–Schiff, simulating the microscopic appearance of Whipple’s disease. Gastric involvement may present with epigastric pain or bleeding, whereas small intestinal disease can present with steatorrhea, diarrhea, protein-losing enteropathy, pseudo-obstruction, or occult bleeding.244

The rare plasma cell proliferative disorder, γ heavy-chain disease, has been associated with abdominal pain, weight loss, and gastric infiltration from malignant plasma cells.245 α Heavy-chain disease, an immunoproliferative small intestinal disease (IPSID), is a mucosa-associated lymphoid-tissue lymphoma characterized by infiltration of the bowel wall resulting in malabsorption and protein-losing enteropathy (see Chapter 29). IPSID is mostly seen in the Mediterranean basin, Middle East, Far East, and Africa, with a recent study suggesting that Campylobacter jejuni may be a causative agent.246

COAGULATION DISORDERS

In hemophiliac individuals, acute abdominal pain can be a manifestation of spontaneous intra-abdominal hemorrhage. Gastrointestinal bleeding may occur from varices related to chronic liver disease secondary to hepatitis C acquired from transfused blood products. von Willebrand’s disease, heparin or warfarin therapy, hepatic failure, qualitative or quantitative platelet defects, and other bleeding diatheses may result in gastrointestinal hemorrhage or intramural hematomas (Table 35-4). Radiologically, intramural bleeding can be recognized by thickened mucosal folds, rigidity, luminal narrowing (Fig. 35-6), and intragastric masses. Intestinal obstruction and intussusception may result.

| Platelet Deficiency |

GI, gastrointestinal.

Hemolytic-uremic syndrome (HUS) consists of a triad of acute kidney injury, microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, and thrombocytopenia without the consumption of humoral clotting factors through defibrination. In children, idiopathic, sporadic, and epidemic cases have variously been described. In adults, HUS occurs in conjunction with complications during childbirth or chemotherapy, with mitomycin C being the most common implicated agent.247 More commonly, adult HUS is preceded by a mild diarrheal illness. Enteric pathogens associated with the HUS prodrome (“HUS colitis”) include Shigella, Salmonella, Yersinia, Campylobacter, and the “hemorrhagic” 0157:H7 strain of Escherichia coli (see Chapter 107).248–252 Undercooked hamburger is the most common vector for 0157:H7 infection with apple juice, radish sprouts, and sausages also implicated in the spread of this infection.248 Several studies suggest that antibiotic therapy of E. coli 0157:H7 with antibiotics increases the risk of development of HUS in children and adults; however, this assertion has been challenged in a meta-analysis.253 Empirical therapy of diarrhea with antimicrobial agents may be appropriate for certain subsets of patients, such as those who are quite clearly at high risk of invasive infections.254 Once HUS appears, colonic involvement is common owing to microangiopathic thrombosis of submucosal vessels and intramural hemorrhage.255 Pancreatitis has also been described.256 Radiographic abnormalities include mucosal irregularities, intestinal dilation, filling defects, bowel wall edema, and findings that may resemble those of idiopathic ulcerative colitis, or vasculitis.257 Because HUS is usually self-limited, therapy consists of hemodialysis and supportive gastrointestinal care. Severe complications may include hemoperitoneum, transmural bowel necrosis with perforation, or colonic stricture.258,259

Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) is an idiopathic disorder consisting of thrombocytopenia, microangiopathic hemolytic anemia (without significant consumption of clotting factors), fever, renal insufficiency, and profound neurologic dysfunction. Compared with HUS, central nervous system (CNS) symptoms predominate in TTP and renal failure is less severe than in HUS—20% of patients have nonspecific abdominal complaints. The bleeding diathesis of TTP can lead to gastrointestinal hemorrhage, but TTP may also cause thrombosis of intestinal vessels that resembles HUS, clinically and pathologically. Acute colitis, cholecystitis, and pancreatitis have been described.260,261 Plasmapheresis allows 90% of patients with TTP to survive an episode without permanent organ damage.255

Venous thromboembolism (VTE), comprising deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism, may be the first manifestation of malignancy. Trousseau’s syndrome refers to migratory superficial thrombophlebitis or DVT occurring in patients with occult cancer. In patients with VTE without a predisposing factor, the incidence of previously undiagnosed cancer was 6% at baseline and 10% from baseline to one year.262 In patients with newly diagnosed VTE, an extensive screening strategy for occult malignancy, which included abdominal imaging and colonoscopy, was superior to a limited screening strategy of medical history, physical examination, and basic blood work in the detection of cancer.263

RED BLOOD CELL DYSCRASIAS

Sickle Cell Disease

Sickle cell disease is an autosomal recessive disorder of hemoglobin structure that is characterized by chronic hemolytic anemia and recurrent episodes of vascular occlusion leading to ischemia and distal tissue infarction in multiple organs. Eight percent of African Americans are heterozygous for the hemoglobin S trait and homozygotes comprise 0.2% of African Americans. Patients with sickle cell anemia and other hemoglobinopathies may develop splenic infarction and liver disease (see following), likely from ischemic injury due to intrasinusoidal sickling and impairment of intrahepatic blood flow and delivery of oxygen to hepatocytes.264,265 Chronic anemia due to hemolysis is typically present and predisposes to an indirect-reacting bilirubin elevation and to the formation of pigmented gallstones.266 Patients with other hereditary defects involving red blood cell cytoskeletal proteins, hereditary spherocytosis, and hereditary elliptocytosis, also have diminished red blood cell survival, leading to an increased incidence of pigmented gallstones. Transfusions are frequently used in the therapy for sickle cell anemia, and therefore such patients who were transfused prior to 1992 are at increased risk for hepatitis C.267 Multitransfused teenage and adult patients with sickle cell anemia also have been found to have degrees of excess hepatic iron stores that are comparable to that noted in thalassemia major.268–270

Sickle cell crisis, an acute manifestation of this disease, is characterized by severe skeletal pain and fever. Abdominal pain is also commonly present, and it is important to distinguish vaso-occlusive crises from surgical conditions such as cholecystitis, bowel infarction, appendicitis, and pancreatitis. Abdominal pain from vaso-occlusive crises tends to be more diffuse and associated with remote pain such as limb and chest pain. The pain of vaso-occlusive crises is typically relieved with hydration and oxygen within 48 hours.271 Sickle cell hepatopathy, a syndrome characterized by severe hyperbilirubinemia out of proportion to degree of ongoing hemolysis, is a rare complication of sickle cell anemia that can be associated with coagulaopthy and encephalopathy, leading to death from acute liver failure. Because treatment with exchange transfusions is associated with improved outcome,272 it is important to distinguish this complication of sickle cell anemia from other causes of liver disease that are common in this patient population.273

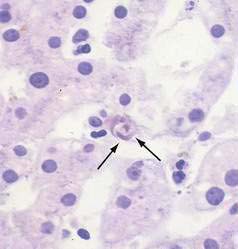

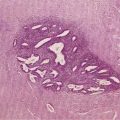

When histologic evaluation of the liver has been performed in patients with sickle cell anemia at autopsy, cholecystectomy or diagnostic percutaneous liver biopsy, dilated sinusoids, erythrophagocytosis by Kupffer cells (Fig. 35-7), and varying degrees of parenchymal atrophy in the central zones of the liver have been observed frequently.265,274–277 In association with hepatic sinusoids engorged by phagocytosed, sickled red blood cells, adjacent areas of ischemic necrosis have been reported in patients with acute episodes of jaundice, right upper quadrant pain, fever, and leukocytosis thought to be secondary to intrahepatic sickle cell crises or sickle cell hepatopathy.264,265,274,276,278 Accumulation of collagen or thin basement membranes within the space of Disse,274 peri-sinusoidal fibrosis,276 and an apparently high incidence of cirrhosis in patients with sickle cell anemia264 has suggested that recurrent ischemic injury secondary to intrahepatic sickling may also be a cause of chronic liver disease.

Although early reports suggested that viral hepatitis was an unusual cause of acute or chronic liver disease in such patients,274,275 studies conducted in the 1980s and 1990s suggested that hepatitis B276,277 and hepatitis C267 are common infections in patients with sickle cell anemia and may account for many episodes of acute or chronic liver disease previously attributed to sickle cell hepatopathy. More recent studies of adult sickle cell anemia patients presenting with acute hepatic dysfunction have found that viral or autoimmune hepatitis plays a role in about a third of such episodes.273 Of special note, intrasinusoidal sickling and Kupffer cell erythrophagocytosis (see Fig. 35-7) almost invariably are found in all patients with sickle cell disease irrespective of apparent cause of liver disease or degree of serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) elevation.277 Intrasinusoidal sickling was also found in two liver biopsies performed after recovery from acute viral hepatitis. To some extent the presence of nonphagocytosed sickled red blood cells in hepatic sinusoids could be attributed to the fact that formalin fixation was noted to induce irreversible sickling of red blood cells in patients with hemoglobin SS or sickle cell disease.277,279 In addition, Omata and colleagues277 have suggested that Kupffer cell erythrophagocytosis may reflect the role of Kupffer cells in clearance of sickled red cells in functionally asplenic patients with sickle cell disease. Thus, assessment of degree of intrasinusoidal sickling or even Kupffer cell erythrophagocytosis is a poor indicator of possible ischemic liver injury in patients with sickle cell disease. In contrast, other features of vascular insufficiency such as acute ischemic necrosis, sinusoidal dilatation and perisinusoidal fibrosis appear to be more specific markers of vascular injury in patients with symptomatic liver dysfunction in the absence of viral hepatitis or other causes for hepatocellular injury.276

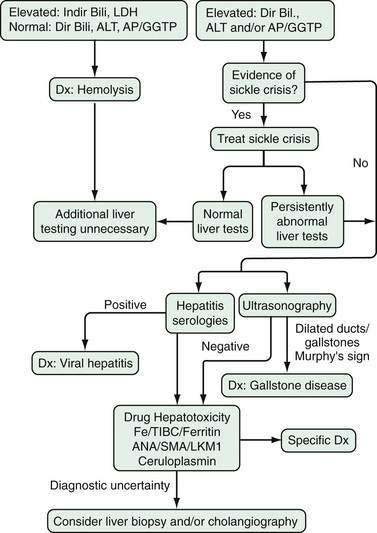

Diggs265 reported in 1965 that 10% of patients presenting with acute sickle crises were jaundiced. More recent assessment of prevalence of liver disease in patients with sickle cell anemia have found persistent abnormalities of one or more liver enzyme tests in 24% of patients followed for sickle cell anemia.279 In addition, 48 of 72 (67%) patients without other biochemical evidence of liver disease had total serum bilirubin levels of greater than 2 mg/dL (greater than 34 µmol/L). Thus laboratory abnormalities suggesting possible liver disease are relatively common in patients with sickle cell disease and frequently lead to diagnostic evaluations as detailed in Figure 35-8. Of note, however, a high rate of complications has been reported in association with liver biopsies performed during acute sickling crises280 and thus invasive diagnostic procedures should be used judiciously in this patient population.