PEPTIC ULCER DISEASE

Case vignette

Approach to the patient

History

Examination

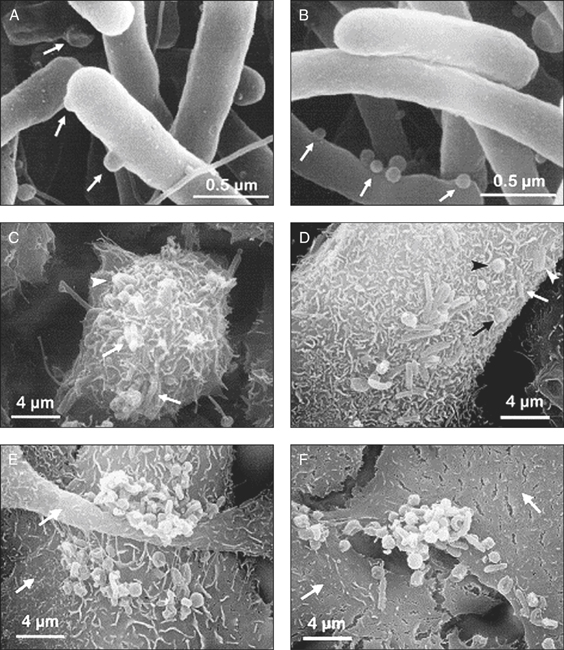

Figure 12.1 Scanning electron micrographs of a 48-h culture of H. pylori (A, B), and infection of cultured AGS cells for 24 h (C, D) or 48 h (E, F). A, blebs (→) protrude from the spiral-shaped bacterial body. B, numerous vesicles (→) are visible on the bacterial surface. C, bacteria are tightly embodied in a dense network of extended microvilli. Spirals are attached horizontally (→) or perpendicularly (arrowhead). D, H. pylori displays various shapes when attached to the cell surface: the spiral (white→), U-shaped (white arrowhead), doughnut (black→), or coccoid form (black arrowhead)

(reprinted from Heczko U, Smith V C, Mark Meloche R et al 2000 Characteristics of Helicobacter pylori attachment to human primary antral epithelial cell. Microbes and Infection 2:8)

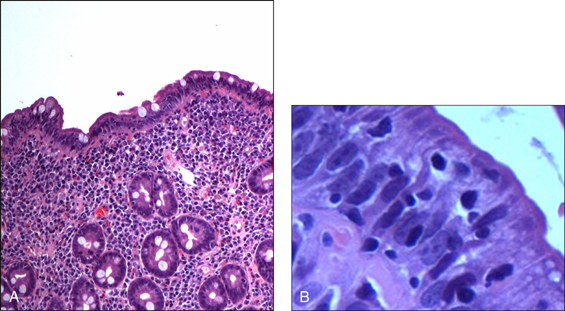

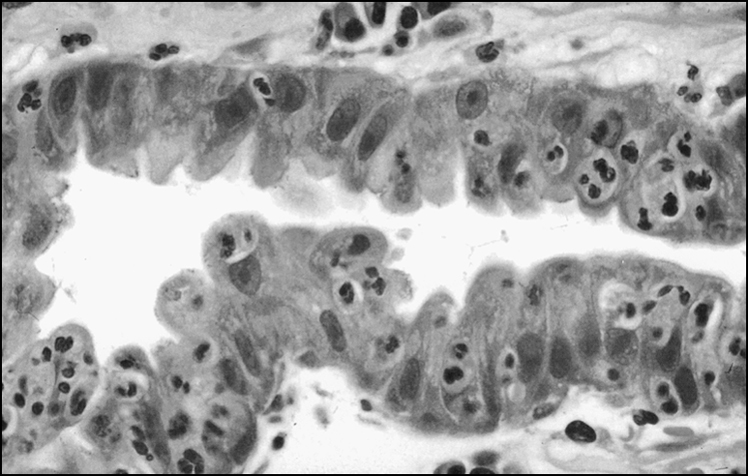

Figure 12.2 Foveolar cells with ‘cobblestoning’. The changes are patchy and often mild. When the cells bulge out, resembling cobblestones, the appearance is almost always diagnostic of H. pylori infection

(reprinted from Robin W J 2000 Gastric pathology associated with Helicobacter pylori. Gastroenterology Clinics of North America 29:47)

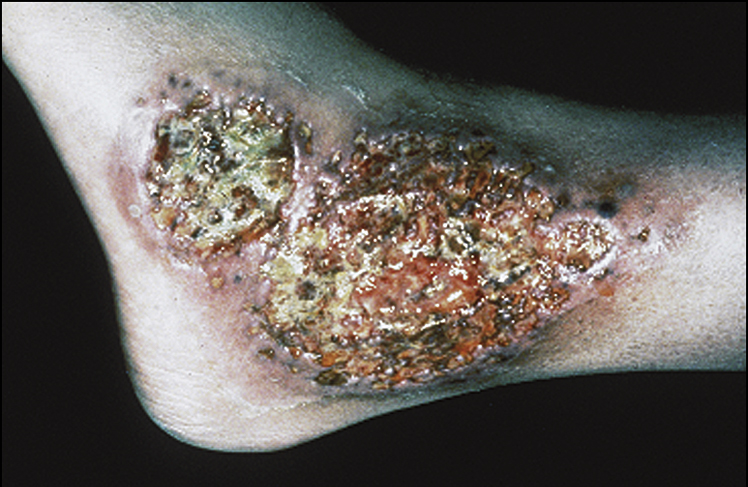

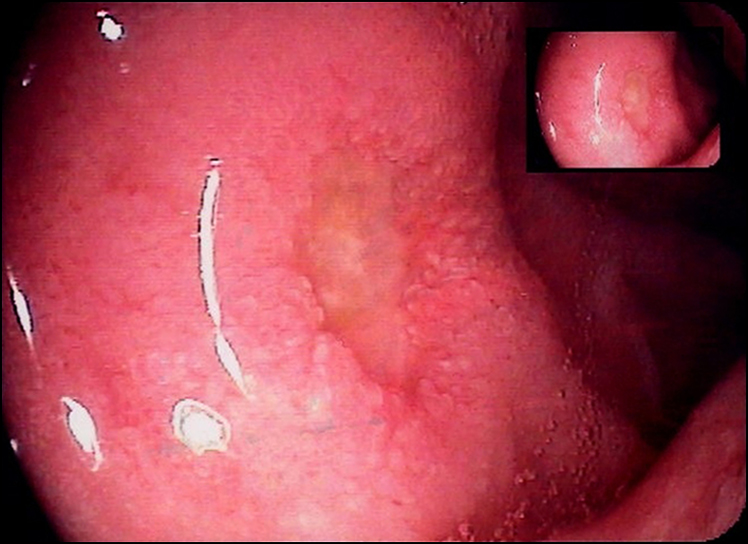

Figure 12.3 Duodenal ulcer

(courtesy of Dr George Ostapowicz)

Investigations

Management

INFLAMMATORY BOWEL DISEASE

Case vignette

Approach to the patient (ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease)

History

Examination

Differential diagnoses in inflammatory bowel disease

Ulcerative colitis

Investigations

Figure 12.6 Barium enema of ulcerative colitis showing pseudopolyposis, lack of haustral markings and straightening of ascending and transverse colon

(reprinted from Kanski J, Pavesio C, Tuft S 2005 Ocular inflammatory disease, Elsevier, fig 8.41)

Management

Acute ulcerative colitis

Maintenance of remission

Advanced management of severe acute ulcerative colitis resistant to IV corticosteroids (upon being treated for at least 7 days)

Crohn’s disease

Investigations

Management

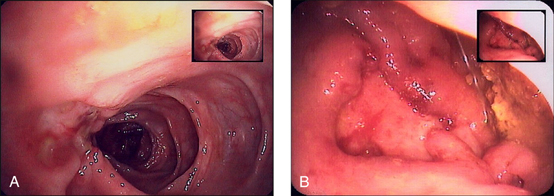

Figure 12.7 Colonic Crohn’s disease

(courtesy of Dr George Ostapowicz)