37 Gastro-intestinal infections

Gastro-intestinal infections represent a major public health and clinical problem worldwide. Many species of bacteria, viruses and protozoa cause gastro-intestinal infection, resulting in two main clinical syndromes. Gastroenteritis is a non-invasive infection of the small or large bowel that manifests clinically as diarrhoea and vomiting. Other infections are invasive, causing systemic illness, often with few gastro-intestinal symptoms. Helicobacter pylori, and its association with gastritis, peptic ulceration and gastric carcinoma, is discussed in Chapter 12.

Epidemiology and aetiology

Gastro-intestinal infections can be transmitted by consumption of contaminated food or water or by direct faecal–oral spread. Air-borne spread of viruses that cause gastroenteritis also occurs. The most important causes of gastro-intestinal infection, and their usual modes of spread, are shown in Table 37.1. In developed countries, the majority of gastro-intestinal infections are food borne. Farm animals are often colonised by gastro-intestinal pathogens, especially Salmonella and Campylobacter. Therefore, raw foods such as poultry, meat, eggs and unpasteurised dairy products are commonly contaminated and must be thoroughly cooked to kill such organisms. Raw foods also represent a potential source of cross-contamination of other foods, through hands, surfaces or utensils that have been inadequately cleaned. Food handlers who are excreting pathogens in their faeces can also contaminate food. This is most likely when diarrhoea is present, but continued excretion of pathogens during convalescence also represents a risk. Food handlers are the usual source of Staphylococcus aureus food poisoning, where toxin-producing strains of S. aureus carried in the nose or on skin are transferred to foods. Bacterial food poisoning is often associated with inadequate cooking and/or prolonged storage of food at ambient temperature before consumption. Water-borne gastro-intestinal infection is primarily a problem in countries without a sanitary water supply or sewerage system, although outbreaks of water-borne cryptosporidiosis occur from time to time in the UK. Spread of pathogens such as Shigella or enteropathogenic Escherichia coli by the faecal–oral route is favoured by over-crowding and poor standards of personal hygiene. Such infections in developed countries are most common in children and can cause troublesome outbreaks in paediatric wards, nurseries and residential children’s homes.

Table 37.1 Important causes of gastro-intestinal infection, their modes of spread and pathogenic mechanisms

| Causative agent | Chief mode(s) of spread | Pathogenic mechanisms |

|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | ||

| Campylobacter | Food, especially poultry, milk | Mucosal invasion |

| Enterotoxin | ||

| Salmonella enterica, non-typhoidal serovars | Food, especially poultry, eggs, meat | Mucosal invasion |

| Enterotoxin | ||

| Salmonella enterica serovars Typhi and Paratyphi | Food, water | Systemic invasion |

| Shigella | Faecal–oral | Mucosal invasion |

| Enterotoxin | ||

| Escherichia coli | ||

| Enteropathogenic | Faecal–oral | Mucosal adhesion |

| Enterotoxigenic | Faecal–oral, water | Enterotoxin |

| Enteroinvasive | Faecal–oral, food | Mucosal invasion |

| Verotoxin-producing | Food, especially beef | Verotoxin |

| Staphylococcus aureus | Food, especially meat, dairy produce | Emetic toxin |

| Clostridium perfringens | Food, especially meat | Enterotoxin |

| Bacillus cereus | ||

| Short incubation period | Food, especially rice | Emetic toxin |

| Long incubation period | Food, especially meat and vegetable dishes | Enterotoxin |

| Vibrio cholerae O1, O139 | Water | Enterotoxin |

| Vibrio parahaemolyticus | Seafoods | Mucosal invasion |

| Enterotoxin | ||

| Clostridium difficile | Faecal–oral (nosocomial) | Cytotoxin |

| Enterotoxin | ||

| Clostridium botulinum | Inadequately heat-treated canned/ preserved foods | Neurotoxin |

| Protozoa | ||

| Giardia lamblia | Water | Mucosal invasion |

| Cryptosporidium | Water, animal contact | Mucosal invasion |

| Entamoeba histolytica | Food, water | Mucosal invasion |

| Viruses | Food, faecal–oral, respiratory secretions | Small intestinal mucosal damage |

Pathophysiology

Clinical manifestations

Many cases of gastro-intestinal infection are asymptomatic or cause subclinical illness. Gastroenteritis is the most common syndrome of gastro-intestinal infection, presenting with symptoms such as vomiting, diarrhoea and abdominal pain. The term ‘dysentery’ is sometimes applied to infections with Shigella (bacillary dysentery) and Entamoeba histolytica (amoebic dysentery), where severe colonic mucosal inflammation causes frequent diarrhoea with blood and pus. Table 37.2 shows the most important causative agents of gastroenteritis together with a brief description of the typical illness that each causes. However, the symptoms experienced by individuals infected with the same organism can differ considerably. This is important because it means that it is rarely possible to diagnose the cause of gastroenteritis on clinical grounds alone.

Table 37.2 Characteristic clinical features of various causes of gastroenteritis

| Causative agent | Incubation period | Symptoms (syndrome) |

|---|---|---|

| Campylobacter | 2–5 days | Bloody diarrhoea |

| Abdominal pain | ||

| Systemic upset | ||

| Salmonella | 6–72 h | Diarrhoea and vomiting |

| Fever; may be associated bacteraemia | ||

| Shigella | 1–4 days | Diarrhoea, fever (bacillary dysentery) |

| Escherichia coli | ||

| Enteropathogenic | 12–72 h | Infantile diarrhoea |

| Enterotoxigenic | 1–3 days | Traveller’s diarrhoea |

| Enteroinvasive | 1–3 days | Similar to Shigella |

| Verotoxin-producing | 1–3 days | Bloody diarrhoea (haemorrhagic colitis) |

| Haemolytic uraemic syndrome | ||

| Staphylococcus aureus | 4–8 h | Severe nausea and vomiting |

| Clostridium perfringens | 6–24 h | Diarrhoea |

| Bacillus cereus | ||

| Short incubation period | 1–6 h | Vomiting |

| Long incubation period | 6–18 h | Diarrhoea |

| Vibrio cholerae O1, O139 | 1–5 days | Profuse diarrhoea (cholera) |

| Vibrio parahaemolyticus | 12–48 h | Diarrhoea, abdominal pain |

| Clostridium difficile | Usually occurs during/just after antibiotic therapy | Diarrhoea, abdominal pain, pseudomembranous enterocolitis |

| Giardia lamblia | 1–2 weeks | Watery diarrhoea |

| Cryptosporidium | 2 days–2 weeks | Watery diarrhoea |

| Entamoeba histolytica | 2–4 weeks | Diarrhoea with blood and mucus (amoebic dysentery), liver abscess |

| Viruses | 1–2 days | Vomiting, diarrhoea |

| Systemic upset | ||

Investigations

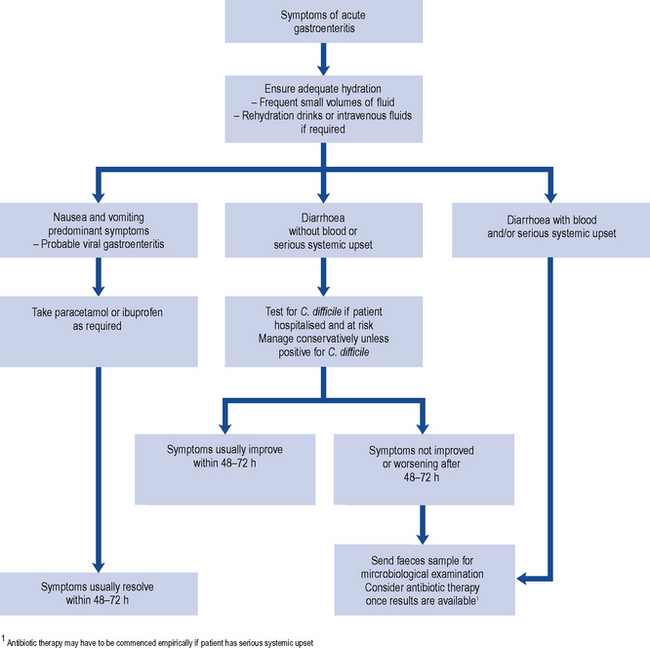

Many cases of gastroenteritis outside hospital are mild and short lived, and microbiological investigation may not be necessary. However, investigations are always recommended where antibiotic therapy is being considered (Fig. 37.1), where there are public health concerns (e.g., if the sufferer works in the food industry) and for gastro-intestinal infections in hospitalised patients.

Treatment

Antiemetics and antidiarrhoeal drugs are discussed in Chapters 34 and 14, respectively. This chapter focuses on the place of antibiotic therapy in gastro-intestinal infections.

Antibiotic therapy

Conditions for which antibiotic therapy is not available or not usually required

None of the presently available antiviral agents are useful in viral gastroenteritis. While most viral infections are self-limiting, chronic viral gastroenteritis can occur in immunocompromised patients. Where possible, immunosuppression should be reduced. Immunoglobulin-containing preparations, administered orally or directly into the duodenum via a nasogastric tube, have also been reported to be effective in managing chronic viral gastroenteritis in immunocompromised patients. As well as human serum immunoglobulin, antibodies from other species (e.g. immunised bovine colostrum) have been used. Immunotherapy of viral gastroenteritis remains experimental, and dosages and frequency of administration of immunoglobulin preparations cannot be recommended (Mohan and Haque, 2002).

At least one study has found that the risk of HUS in children with diarrhoea due to VTEC was much higher in those who received antibiotics. On that basis, it is advised in the UK that antibiotics are contraindicated in children with VTEC infection (National Collaborating Centre for Women’s and Children’s Health, 2009).

Conditions for which antimicrobial therapy may be considered

The place for antibiotics in the management of uncomplicated gastroenteritis due to bacteria such as Salmonella and Campylobacter is not clear cut. Certain antibiotics are reasonably effective in reducing the duration and severity of clinical illness and in eradicating the organisms from faeces. However, many microbiologists are cautious about the widespread use of antibiotics in diarrhoeal illness because of the risk of promoting antibiotic resistance (Sack et al., 1997). Another difficulty with respect to antibiotic prescribing is that it is not usually possible to determine the aetiological agent of diarrhoea on clinical grounds, and stool culture takes at least 48 h. Patients with severe illness, especially systemic symptoms, may require antibiotic therapy before the aetiological agent has been established. In such circumstances, a fluoroquinolone antibiotic such as ciprofloxacin would usually be the most appropriate empiric agent, at least in patients in whom CDI is considered unlikely or has been excluded. Otherwise, it is reasonable to limit antibiotic use to microbiologically proven cases where there is serious underlying disease and/or continuing severe symptoms. Antibiotics may also be used to try to eliminate faecal carriage, for example, in controlling outbreaks in institutions, or in food handlers who may be prevented from returning to work until they are no longer excreting gastro-intestinal pathogens.

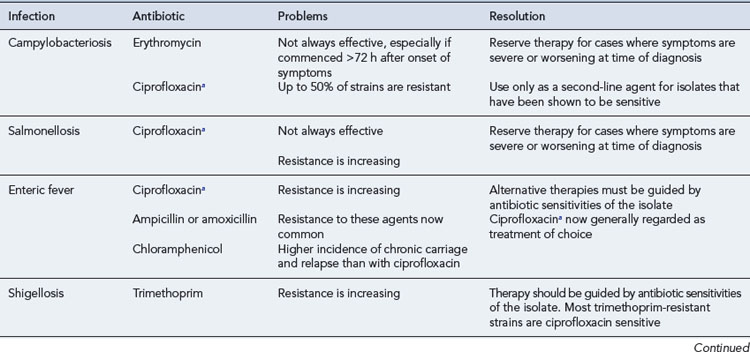

Campylobacteriosis

Erythromycin is effective in terminating faecal excretion of Campylobacter. Some studies have shown that treatment commenced within the first 72–96 h of illness can also shorten the duration of clinical illness, especially in patients with severe dysenteric symptoms. The recommended dosage for adults is 250–500 mg four times a day orally for 5–7 days, and for children 30–50 mg/kg/day in four divided doses. Clarithromycin 250–500 mg (children under 1 year, 7.5 mg/kg; 1–2 years, twice a day; 3–6 years, 125 mg; 7–9 years, 5–7 days) or azithromycin 500 mg (children 10 mg/kg) once daily for 3 days are also effective. Ciprofloxacin, at a dose of 500 mg twice daily orally for adults, may also be effective in Campylobacter enteritis. However, whereas resistance rates to erythromycin have generally remained below 5%, resistance to ciprofloxacin has emerged, exceeding 10% in the UK and 50% in some countries (Dingle et al., 2005).

Salmonellosis

Most cases of Salmonella gastroenteritis are self-limiting and antibiotic therapy is unnecessary. However, antimicrobial therapy of salmonellosis is routinely recommended for infants aged under 6 months and immunocompromised patients, who are susceptible to complicated infections. Most antibiotics, even those with good in vitro activity, do not alter the course of uncomplicated Salmonella gastroenteritis. However, the fluoroquinolones, such as ciprofloxacin, can often shorten both the symptomatic period and the duration of faecal carriage. Ciprofloxacin resistance is now seen in up to 10% of non-typhoidal serovars of S. enterica in some countries but is still uncommon in the UK (Murray et al., 2005). The recommended dose of ciprofloxacin for adults is 500 mg twice daily orally for 1 week. Fluoroquinolones are not licensed for this indication in children, although there is increasing evidence that they can safely be given to children. The recommended dose of ciprofloxacin in childhood is 7.5 mg/kg twice daily orally. Trimethoprim at a dose of 25–100 mg twice daily orally may be used in children if it is preferred not to use a fluoroquinolone.

E. coli infections

While most infections with enteropathogenic E. coli can be managed conservatively, small trials suggest that trimethoprim may be effective, especially in controlling nursery or hospital outbreaks. On the basis that enteroinvasive E. coli are closely related to Shigella and cause a similar clinical syndrome, similar therapy may be appropriate. Antibiotic therapy for traveller’s diarrhoea caused by enterotoxigenic E. coli infection is often unnecessary, but troublesome symptoms will often respond to a single dose of ciprofloxacin or azithromycin, the need for further doses depending on clinical response. Alternatively, a 3–5 day course of trimethoprim may be given, although resistance is becoming increasingly common in some areas. Rifaximin is a new non-absorbable antibiotic that is available in a number of countries. It appears to be as effective as ciprofloxacin in treating E. coli-predominant traveller’s diarrhoea but is ineffective in patients with inflammatory or invasive enteropathogens (Robins and Wellington, 2005). The dose for adults is 200 mg three times per day for 3 days.

Conditions for which antimicrobial therapy is usually indicated

Shigellosis

Shigella sonnei, which accounts for most cases of shigellosis in the UK and most other industrialised countries, usually causes a mild self-limiting illness. Even if not required on clinical grounds, antibiotic therapy for shigellosis is usually recommended in order to eliminate faecal carriage, and therefore prevent person-to-person transmission. In contrast to salmonellosis, a number of antibiotics may be effective in shortening the duration of illness and terminating faecal carriage. This is especially true of strains of S. sonnei that are endemic in industrialised countries, whereas in developing countries, Shigella species that are multiple antibiotic resistant are an increasing problem. The fluoroquinolones are highly effective in shigellosis and resistance is rare; therefore, they are often considered to be the treatment of choice, especially in adults and/or for treating imported infections. The dose of ciprofloxacin is 500 mg twice daily orally in adults (7.5 mg/kg twice daily in children). Amoxicillin is an alternative first-line drug for S. sonnei infections acquired in the UK, where around 90% of isolates are susceptible. The dose of amoxicillin is 250–500 mg three times daily in adults, and 62.5–125 mg three times daily in children. Azithromycin (doses as for campylobacteriosis) is increasingly recommended as an alternative agent for shigellosis, especially in children (Jain et al., 2005). Third-generation cephalosporins such as ceftriaxone are another option for severe shigellosis. Trimethorpim resistance is now common, so this agent can no longer be recommended as empiric therapy. Antibiotic therapy is usually given for a maximum of 5 days.

Enteric fever

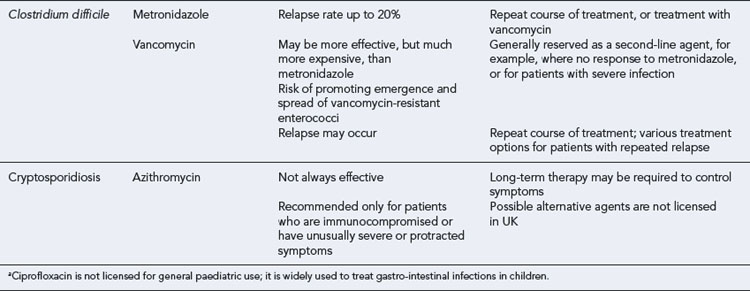

Recurrence of symptoms occurs in about 20% of patients treated for CDI. Although some recurrences are due to germination of spores that have persisted in the colon since the original infection, it is recognised that some of these cases are due to reinfection, rather than relapse caused by the original strain (Loo et al., 2004). Most recurrences respond to a further 10–14 day course of metronidazole or vancomycin, but a few patients experience repeated recurrences. There is no reliable means of managing these patients. Options include:

Trial data do not currently support the use of probiotics for the treatment or prevention of CDI (Department of Health and Health Protection Agency, 2009).

Cryptosporidiosis

Cryptosporidiosis in immunocompetent individuals is generally self-limiting. However, in immunosuppressed patients, severe diarrhoea can persist indefinitely and can even contribute to death. HIV-infected patients on highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) now have a much lower incidence of cryptosporidiosis due to immune reconstitution, and possibly a direct anti-cryptosporidium effect of protease inhibitors. There is no reliable antimicrobial therapy. Azithromycin, which is readily prescribable, is partially effective at a dose of 500 mg once daily (10 mg/kg once daily in children). Treatment should be continued until Cryptosporidium oocysts are no longer detectable in faeces (typically 2 weeks), to minimise the risk of relapse post-treatment. Occasionally, therapy has to be continued indefinitely to prevent relapse. Most other agents that have been recommended for treatment of cryptosporidiosis, for example, nitazoxanide, spiramycin, paromomycin and letrazuril, are not licensed in the UK. These can usually be sourced from special order manufacturing or importing companies (Smith and Corcoran, 2004). Of these agents, nitazoxanide has FDA approval in the USA, and has been shown to be effective in clinical trials at a dose of 500 mg twice daily (adults and children aged 12 years and over) for 3 days (children 1–3 years 100 mg bd; 4–11 years 200 mg bd). However, it is not effective unless the patient is able to mount an appropriate immune response.

Amoebiasis

The aim of treatment in amoebiasis is to kill all vegetative amoebae and also to eradicate cysts from the bowel lumen. Metronidazole is highly active against vegetative amoebae and is commonly the treatment of choice for acute amoebic dysentery and amoebic liver abscess. The dose for adults is 800 mg (children 100–400 mg) three times daily for 5–10 days. To eradicate cysts, metronidazole therapy is followed by a 5-day course of diloxanide furoate 500 mg three times daily (20 mg/kg daily in three divided doses for children). Tinidazole has recently been shown to reduce clinical failure and be better tolerated than metronidazole (Gonzales et al., 2009). The dose of tinidazole for adults is 2 g daily for 2–3 days, and for children, 50–60 mg/kg daily for 3 days.

Patient care

Common therapeutic problems in the management of gastro-intestinal infection are summarised in Table 37.3. Problems associated with specific gastro-intestinal infections are summarised in Table 37.4.

Table 37.3 Practice points: general problems with treatment of gastro-intestinal infections

| Problems | Resolution |

|---|---|

| Difficult or impossible to make a rapid aetiological diagnosis | Hospital laboratories are expected to offer rapid testing for C. difficile 7 days per week |

| New, more accurate, diagnostic tests for viral gastroenteritis are becoming more widely available | Few other recent improvements in the diagnosis of bacterial or parasitic infections |

| Clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of antibiotic therapy for many bacterial gastro-intestinal infections are not clearly established | Without reliable data showing benefit, antimicrobial therapy is not used in the majority of infections |

| No specific therapies for viral gastroenteritis | Infections in otherwise healthy individuals are generally self-limiting |

| Various non-evidence-based experimental treatments have been used to manage immunocompromised patients with protracted diarrhoea | |

| Acute illness may be followed by a period of non-infective diarrhoea | Cautious use of antidiarrhoeal medication may be indicated at this stage |

Answers

Answers

Answers

Dingle K.E., Clarke L., Bowler I.C. Ciprofloxacin resistance among human Campylobacter isolates 1991–2004: an update. J. Antimicrob. Chemother.. 2005;55:395-396.

Department of Health and Health Protection Agency. Clostridium Difficile Infection: How to Deal with the Problem. London: Department of Health; 2009.

Gonzales M.L.M., Dans L.F., Martinez E.G. Antiamoebic drugs for treating amoebic colitis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews.. 2009. Issue 2 Art No. CD006085. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006085

Jain S.K., Gupta A., Glanz B., et al. Antimicrobial-resistant Shigella sonnei: limited antimicrobial treatment options for children and challenges of interpreting in vitro azithromycin susceptibility. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J.. 2005;24:494-497.

Loo V.G., Libman M.D., Miller M.A., et al. Clostridium difficile: a formidable foe. Can. Med. Assoc. J.. 2004;171:47-48.

Mohan P., Haque K. Oral immunoglobulin for the prevention of rotavirus infection in low birth weight infants. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews.. 2002. Issue 3. Art. No.: CD003740. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003740

Murray A., Coia J.E., Mather H., et al. Ciprofloxacin resistance in non-typhoidal Salmonella serotypes in Scotland, 1993–2003. J. Antimicrob. Chemother.. 2005;56:110-1104.

National Collaborating Centre for Women’s and Children’s Health. Diarrhoea and Vomiting Caused by Gastroenteritis: Diagnosis, Assessment and Management in Children Younger Than 5 Years. London: RCOG Press; 2009.

Robins G.W., Wellington K. Rifaximin: a review of its use in the management of traveller’s diarrhea. Drugs. 2005;65:1697-1713.

Sack R.B., Rahman M., Yunus M., et al. Antimicrobial resistance in organisms causing diarrheal disease. Clin. Infect. Dis.. 1997;24(Suppl. 1):S102-S105.

Smith H.V., Corcoran G.D. New drugs and treatment for cryptosporidiosis. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis.. 2004;17:557-564.

Bhan M.K., Bahl R., Bhatnagar S. Typhoid and paratyphoid fever. Lancet. 2005;366:749-762.

DuPont H.L. What’s new in enteric infectious diseases at home and abroad. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis.. 2005;18:407-412.

Loeb M., Smaill F., Smieja M., editors. Evidence-Based Infectious Diseases. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009.

Starr J. Clostridium difficile associated diarrhoea: diagnosis and treatment. Br. Med. J.. 2005;331:498-501.

Townes J.M. Acute infectious gastroenteritis in adults. Seven steps to management and prevention. Postgrad. Med.. 2004;115:11-19.

Yoshikawa T.T., Norman D.C., editors. Diseases in the Ageing. A Clinical Handbook. New York: Springer, 2009.