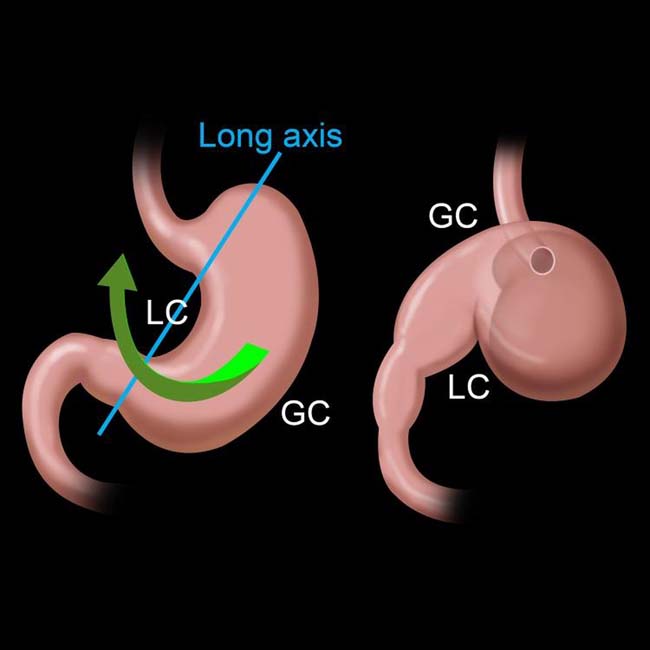

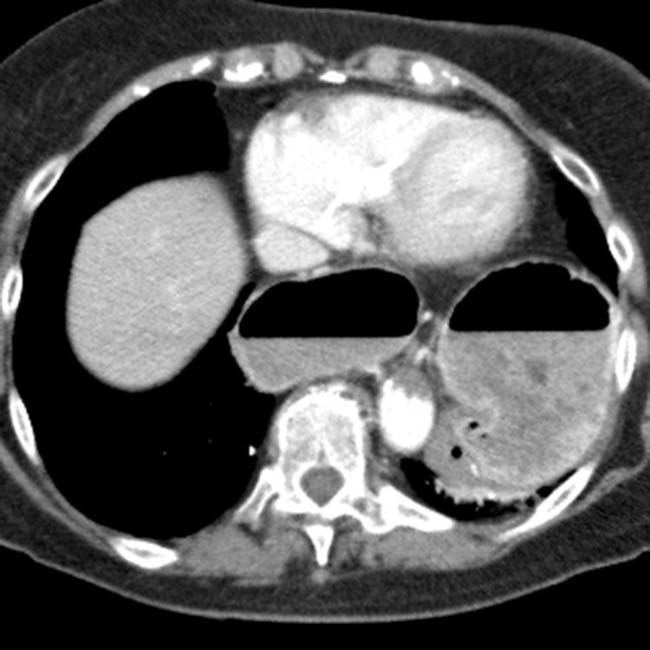

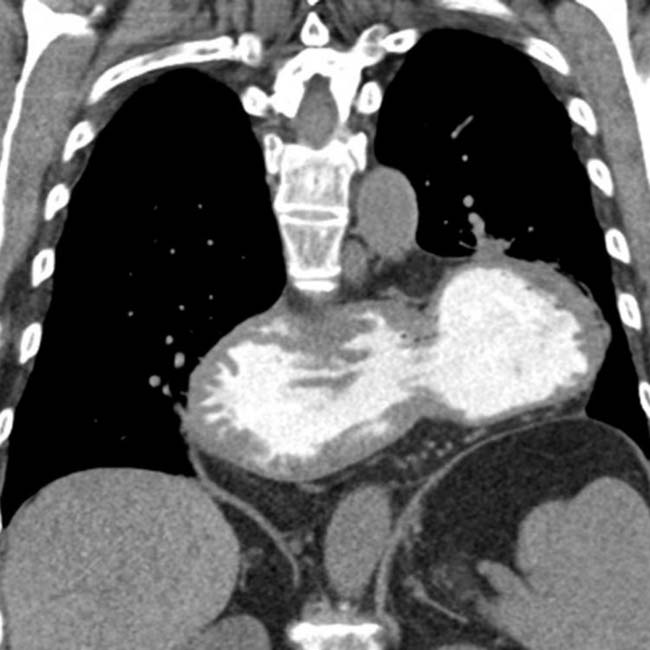

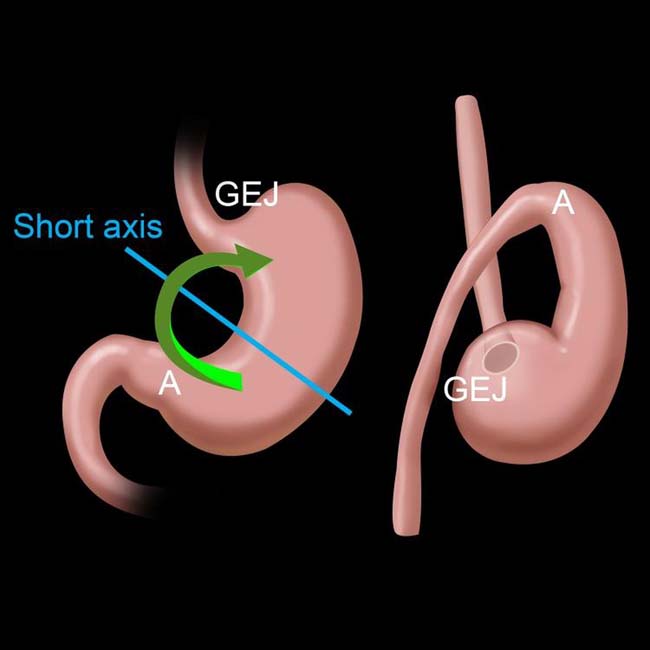

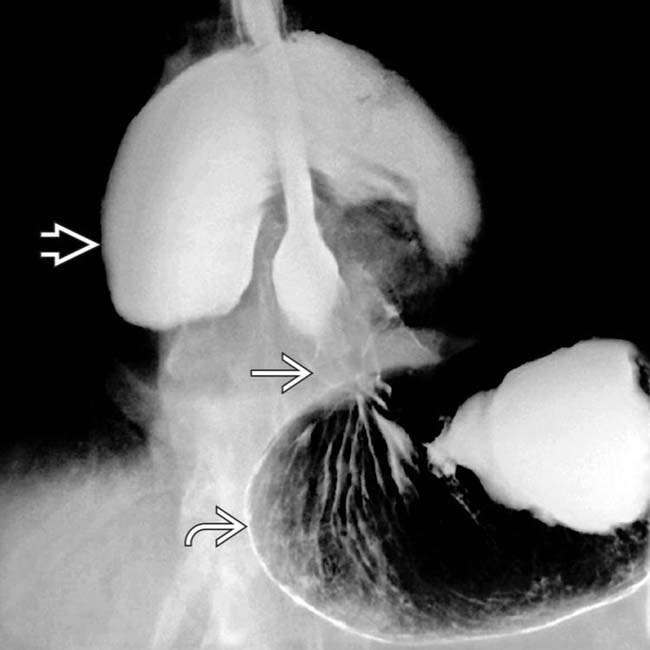

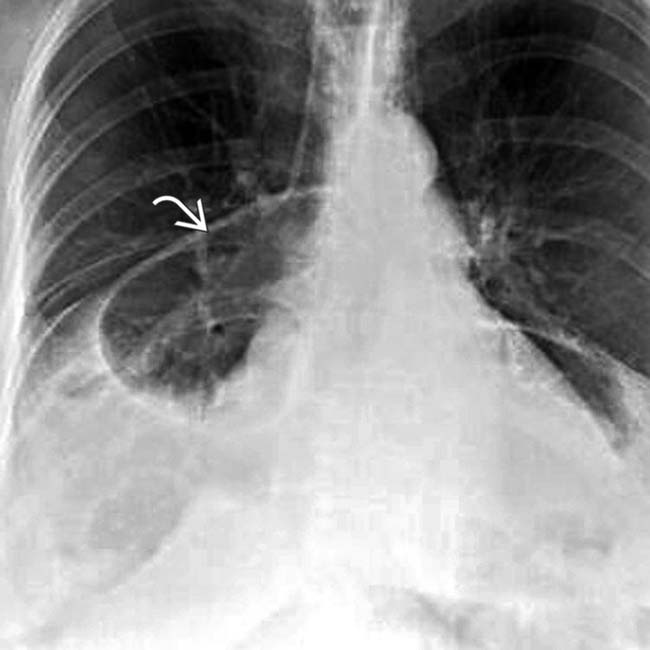

Most common type; “upside-down stomach”

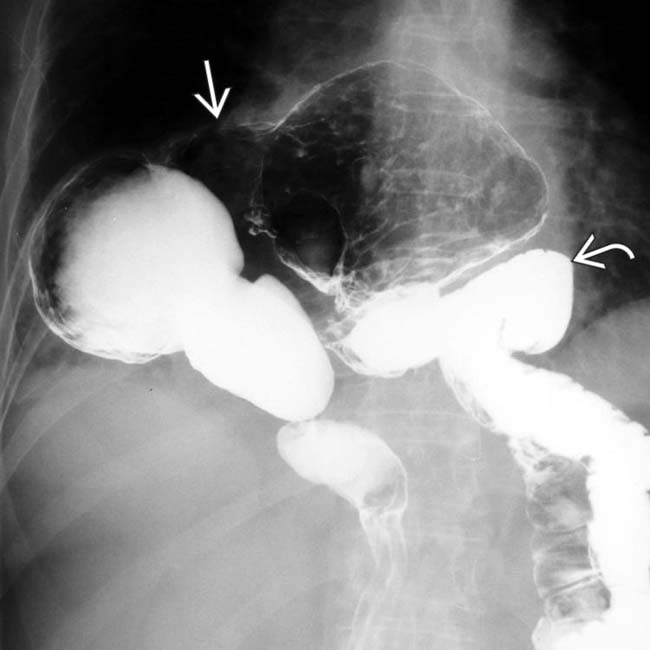

lies above the lesser curvature. The small bowel

lies above the lesser curvature. The small bowel  is also herniated through a large diaphragmatic defect.

is also herniated through a large diaphragmatic defect.

IMAGING

General Features

CLINICAL ISSUES

Presentation

Natural History & Prognosis

also lies within the chest.

also lies within the chest.

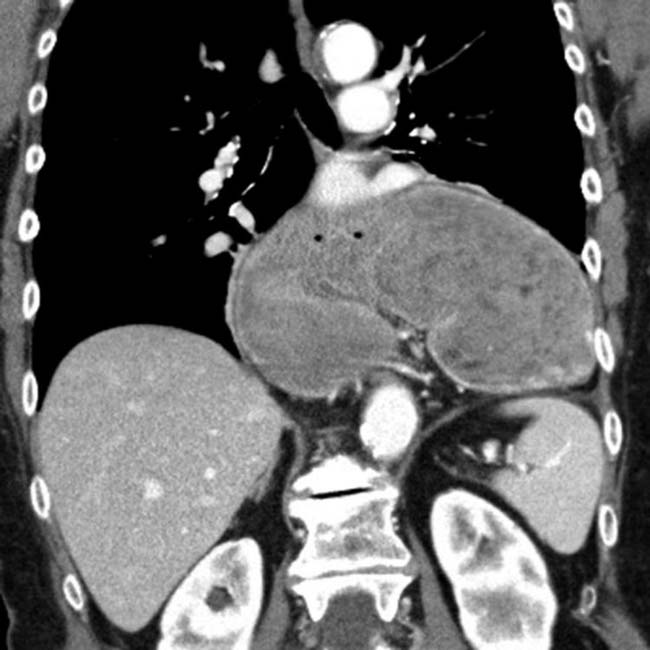

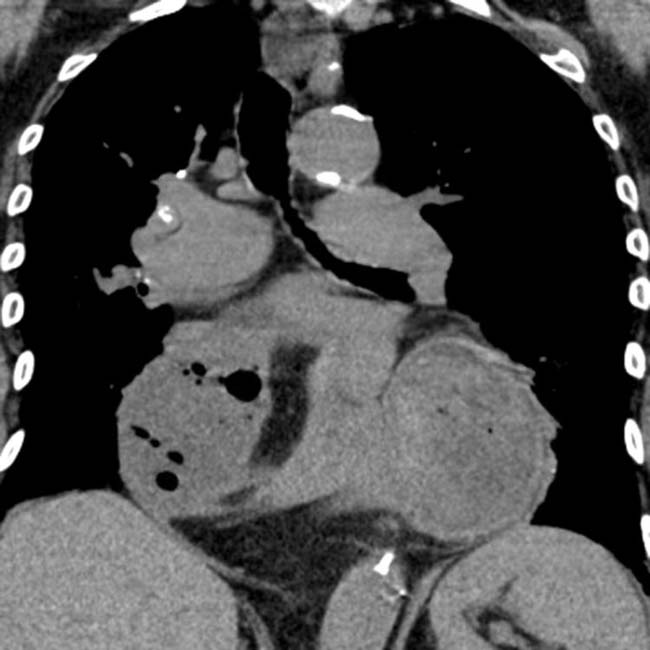

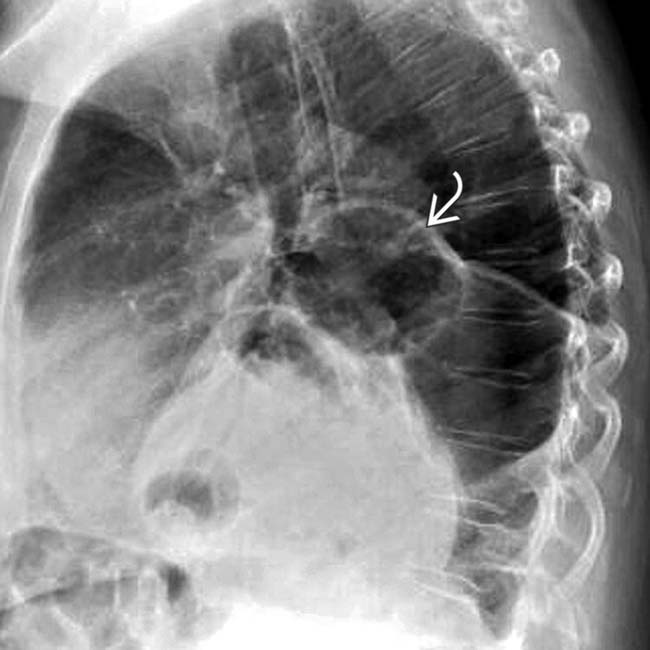

lies lower than the antrum and pylorus. This could be considered organoaxial “position” versus “volvulus,” and no obstruction is present.

lies lower than the antrum and pylorus. This could be considered organoaxial “position” versus “volvulus,” and no obstruction is present.

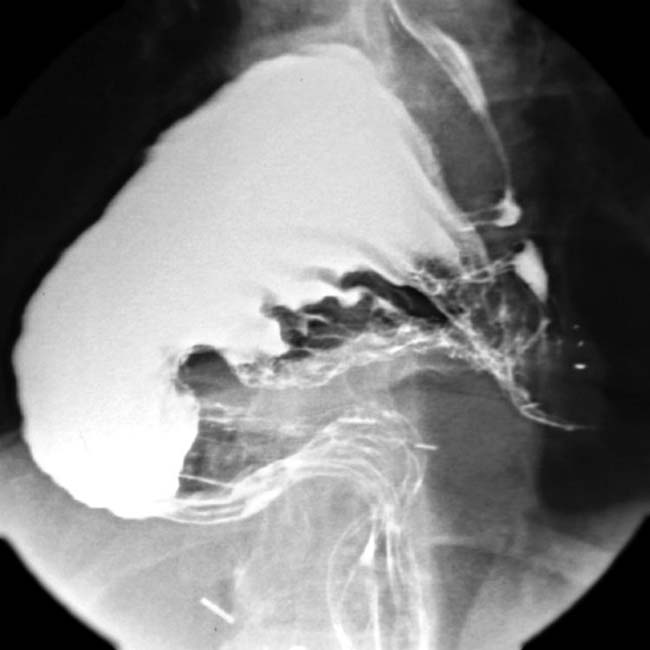

nearly 2 hours after its administration.

nearly 2 hours after its administration.

with retained contrast in its lumen.

with retained contrast in its lumen.

. The patient was felt to be at least partially obstructed, and underwent operative repair, where the organoaxial volvulus was confirmed.

. The patient was felt to be at least partially obstructed, and underwent operative repair, where the organoaxial volvulus was confirmed.

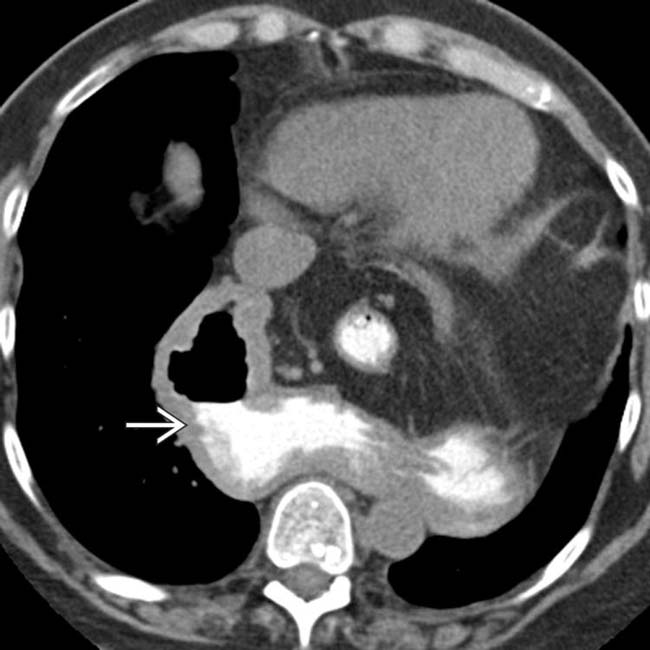

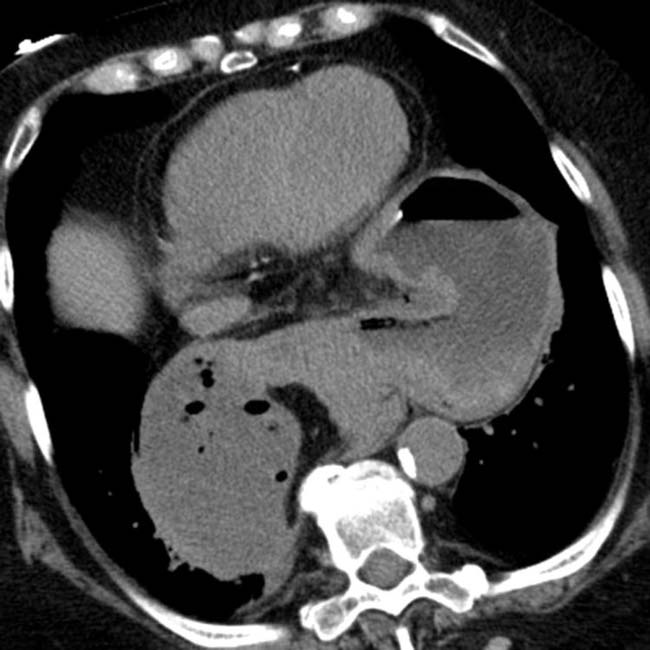

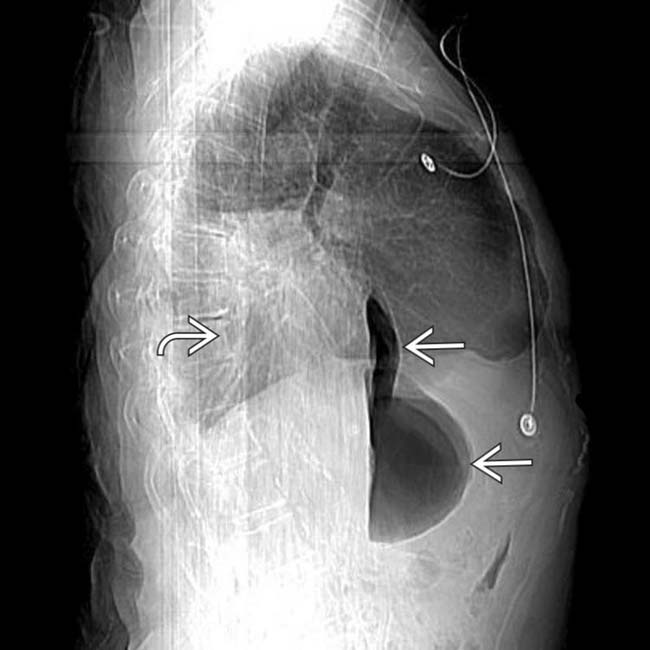

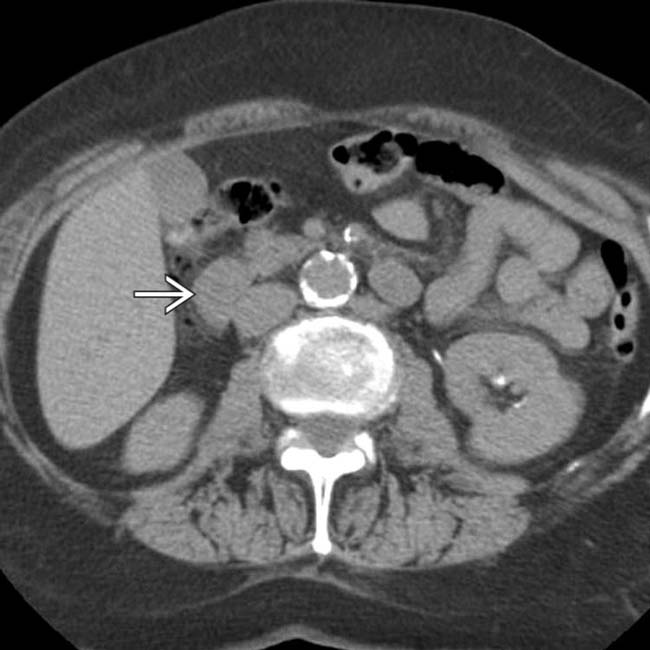

is narrowed as it enters the abdomen.

is narrowed as it enters the abdomen.

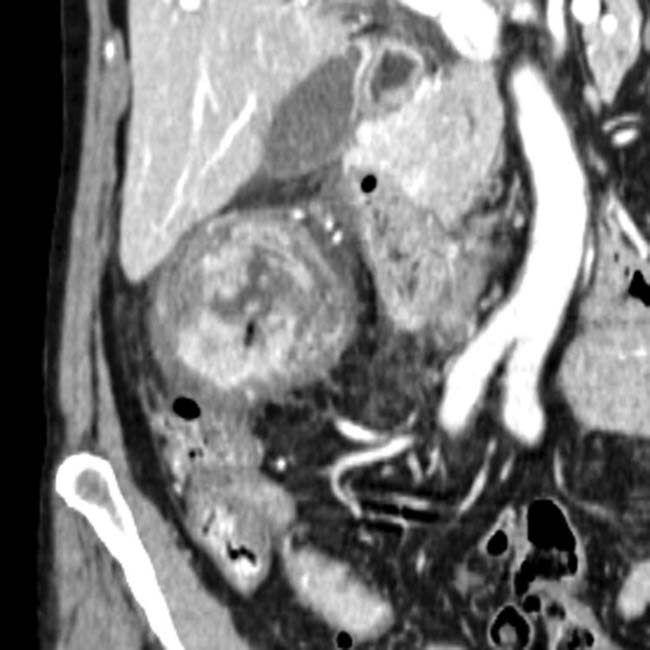

and fundus

and fundus  in the abdomen. The body and antrum of the stomach

in the abdomen. The body and antrum of the stomach  are in the chest and are twisted and compressed as they traverse the diaphragm, constituting a mesenteroaxial volvulus with obstruction.

are in the chest and are twisted and compressed as they traverse the diaphragm, constituting a mesenteroaxial volvulus with obstruction.

and retrocardiac mass effect

and retrocardiac mass effect  .

.

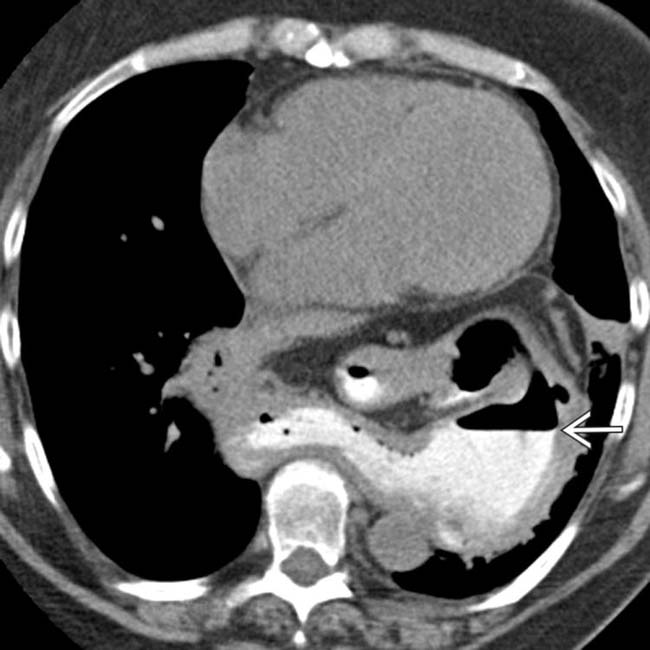

, and the retrocardiac fluid-density mass

, and the retrocardiac fluid-density mass  .

.

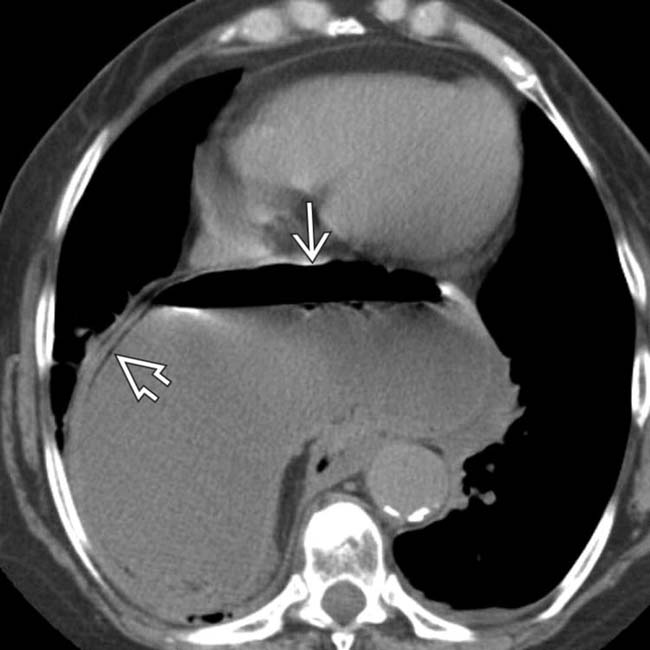

, along with pneumatosis in the gastric wall

, along with pneumatosis in the gastric wall  , indicating ischemic injury.

, indicating ischemic injury.

within the distended stomach, and additional evidence of gastric pneumatosis

within the distended stomach, and additional evidence of gastric pneumatosis  . The larger collection of gas and fluid is within the gastric body and antrum, which lie in the thorax, while the smaller collection is within the intraabdominal gastric fundus.

. The larger collection of gas and fluid is within the gastric body and antrum, which lie in the thorax, while the smaller collection is within the intraabdominal gastric fundus.

within the gastric fundus

within the gastric fundus  .

.

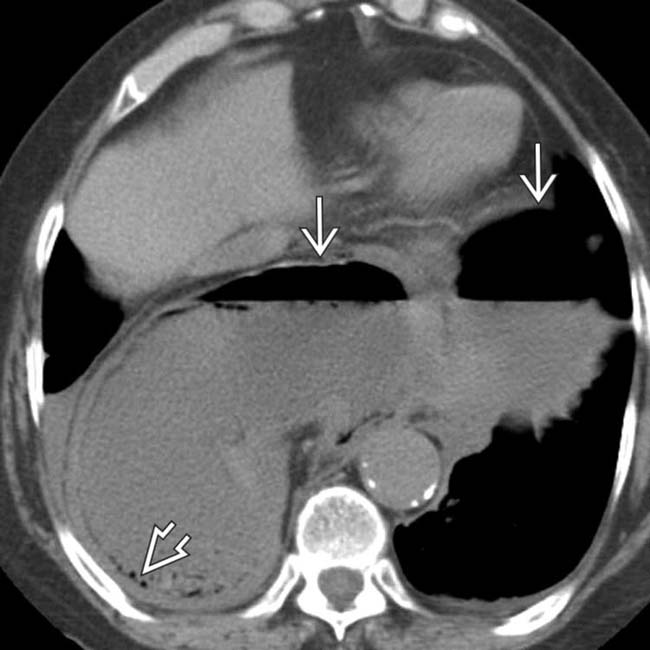

and small bowel due to the incarcerated gastric volvulus. Volvulus and gastric infarction were confirmed at surgery.

and small bowel due to the incarcerated gastric volvulus. Volvulus and gastric infarction were confirmed at surgery.

.

.

due to volvulus with acute obstruction.

due to volvulus with acute obstruction.