CHAPTER 47 GASTRIC INJURIES

The stomach is a relatively thick-walled, well-vascularized organ that is variably positioned in the peritoneal cavity. Although partially protected by the lower rib cage, its size and location put the stomach at risk for injury, particularly with injury from penetrating trauma to the abdomen or lower chest.

INCIDENCE

Gastric injuries usually result from penetrating trauma and occur in approximately 20% of gunshot wounds and 10% of stab wounds.1–3 Blunt gastric trauma is much less common. The American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (East) multi-institutional study on hollow viscus injury reported that the prevalence of blunt gastric rupture was 0.06% in patients undergoing evaluation for blunt abdominal trauma and 2.1% of all patients found to have hollow viscus injury.4

MECHANISM OF INJURY

The stomach is at risk for injury after stab wounds to the left thoracoabdominal region of the body. A single perforation occurs in over 50% of these cases.2 However, injury to adjacent organs is common. Gunshot wounds result in two or more gastric wounds in 90% of cases.2 Although often associated with some surrounding tissue damage to the stomach, this is usually only significant with high-velocity missiles. Shotgun wounds at close range (<15 feet) are often associated with massive destruction of the abdominal wall, stomach, and other intra-abdominal organs.

Blunt injury to the stomach is most often the result of motor vehicle crashes, or motor vehicle–pedestrian trauma.5–7 Less common causes include falls, assaults, and improperly performed cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Blunt gastric injuries include linear lacerations and complete gastric rupture. The postulated mechanisms for blunt gastric injury include sudden increases in intraluminal pressure resulting in a balloon-bursting type of phenomenon of a full stomach, compression against the spine (seat-belt injury), or a deceleration injury with shearing forces resulting in a laceration of the anterior stomach wall.

DIAGNOSIS

Patients with stab wounds and hypotension, peritonitis, or both should undergo laparotomy immediately. Asymptomatic patients without central nervous system injury (brain or spinal cord injury) or drug or alcohol involvement may be observed with repeated physical exams. In other patients, local wound exploration, diagnostic peritoneal lavage (DPL), or laparoscopy are alternatives. Laparoscopy is most helpful with thoracoabdominal stab wounds in identifying associated injuries to the diaphragm.8 Focused assessment with sonography for trauma (FAST) may not identify the small amount of fluid initially associated with hollow viscus injury, and thus may be misleading with isolated gastric injuries.

Early operation is indicated for symptomatic gunshot wounds to the abdomen. Occasionally, a tangential gunshot wound in a stable patient may be observed, or such a wound may be found after the patient undergoes either DPL or laparoscopy. Abdominal CT is also helpful in this situation. In patients suspected to have either blunt or penetrating gastric injury, the placement of a nasogastric tube is helpful. Not only does proper placement of a nasogastric tube minimize the risk of aspiration, but a bloody aspirate when present is highly suspicious for a gastric injury. In patients with blunt gastric injury and no obvious peritoneal signs, a supine film of the abdomen discloses free air in less than 50% of cases. In this situation, abdominal CT is more sensitive in identifying free air.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

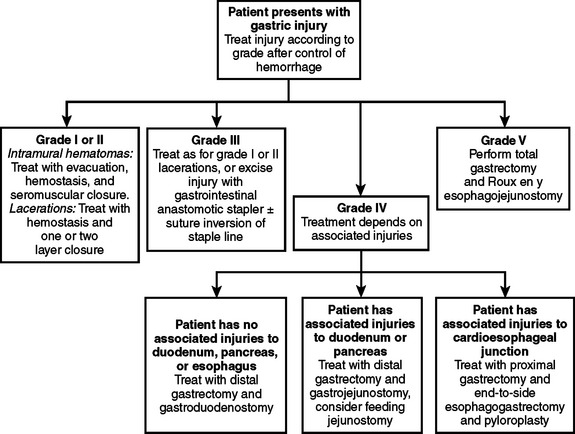

Gastric injuries thus identified are treated according to their severity (Table 1, Figure 1). Most intramural hematomas (grades I and II) are treated by careful evacuation, hemostasis, and closure with seromuscular sutures made of nonabsorbable material. Small grade I and II perforations can be closed in one or two layers. Because of the vascularity of the stomach, I prefer a two-layer closure after hemostasis is achieved.

| AAST Grade | Characteristics of Injury |

|---|---|

| I | Intramural hematoma <3 cm, partial thickness laceration |

| II | Intramural hematoma >3 cm; small (<3 cm) laceration |

| III | Large (>3 cm) laceration |

| IV | Large laceration involving vessels of greater or lesser curvature |

| V | Extensive (>50%) rupture; stomach devascularization |

AAST, American Association for the Surgery of Trauma.

Modified from American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST).

Large (grade III) injuries near the greater curvature can be closed by the same technique or by the use of a GIA stapler. Certain defects may also be closed using a TA stapler. The staple line may be protected with a seromuscular closure using nonabsorbable sutures. Care must be taken to avoid stenosis in the gastroesophageal and pyloric area. A pyloric wound may be converted to a pyloroplasty to avoid possible stenosis in this area. Extensive wounds (grade IV) may be so destructive that a proximal or distal gastrectomy is required. Reconstruction with either a Billroth I or II anastomosis is dictated by the presence or absence of an associated duodenal injury. In rare cases, a total gastrectomy and a Roux-en-Y esophojejunostomy are necessary for severe injuries (grade V).

If a diaphragm injury occurs in association with a gastric perforation, contamination of pleural cavity with gastric contents can be problematic.9 Under most circumstances, it is sufficient to clear the pleural space through the diaphragmatic rent after closure of the gastric perforation. It may be necessary to enlarge the diaphragmatic injury to achieve complete evacuation of the pleural contamination. After surgical repair of the stomach, the diaphragm injury is closed, and a chest tube is placed. Occasionally, the contamination may be so severe, particularly if operation is delayed, that a separate thoracotomy to provide adequate drainage of the pleural space is necessary. Thoracoscopic evacuation of the gastric contamination of the pleural space followed by chest tube placement is another option.

MORTALITY

Mortality after gastric injury is related to the mechanism of injury and the presence of shock and transfusion requirements, as well as the number of associated injuries. The mortality associated with blunt gastric rupture has been reported to range from 0% to 66% and averages around 30%.4–8 Associated intra- and extra-abdominal injuries are usually present. The intra-abdominal organs most frequently injured include the spleen, liver, small bowel, and pancreas. The most frequent extra-abdominal injuries include chest, extremity, and head. Hemorrhagic shock and complications related to the associated injuries account for the vast majority of deaths.

The overall mortality rate for penetrating gastric injuries is 14%–20%.1–3 Early deaths are related to irreversible hemorrhagic shock from associated injuries. Mortality increases dramatically with the number of organs injured. The most common associated injuries include the liver, diaphragm, colon, lung, and small bowel. Injuries to the spleen, pancreas, and major blood vessels in the abdomen are also common. Mortality after either penetrating or blunt gastric injury rarely is the result of injury to the stomach. When it occurs, it is related to anastomotic dehiscence, abscess or fistula formation, and subsequent organ failure.

MORBIDITY

Major morbidity after gastric injury includes intra-abdominal abscess formation, bleeding, anastomotic breakdown, and empyema formation.3,6 The severity of gastric injury and degree of contamination contribute to the development of intra-abdominal abscess formation. Intra-abdominal contamination is often significantly greater after blunt gastric injury.

After penetrating trauma, the incidence of intra-abdominal abscess formation and surgical site infection is similarly low for both isolated gastric and colonic injury. The low incidence of intra-abdominal abscess formation with either isolated stomach or colon injury increases dramatically when concomitant injuries to the liver, kidney, pancreas, or duodenum are present.10,11 There is even a greater synergistic effect on intra-abdominal abscess formation with combined stomach and colon injuries. The risk of empyema increases significantly when there is a diaphragm injury in association with penetrating injuries to the stomach. Bleeding can occur from the surgical site or gastric suture line, and may require reoperation. Occasionally suture line bleeding may be controlled using endoscopic techniques. In the rare instances of gastric injuries that require resection and anastomosis, anastomotic stenosis may require revision.

1 Nicholas JM, Parker Rix E, Esley KA, et al. Changing patterns in the management of penetrating abdominal trauma: the more things change, the more they stay the same. J Trauma. 2003;55:1095-1110.

2 Durham RM, Olson S, Weigelt JA. Penetrating injuries to the stomach. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1991;172:298-302.

3 Coimbra R, Pinto MCC, Aguir JR, Rasslan S. Factors related to the occurrence of postoperative complications following penetrating gastric injuries. Injury. 1995;26:463-466.

4 Watts DD, Fakry SM. EAST Multi-Institutional Hollow Viscus Injury Research Group. Incidence of hollow viscus injury in blunt trauma: an analysis from 275,557 trauma admissions from the EAST multi-institutional trial. J Trauma. 2003;54:289-294.

5 Shinkawa H, Yasuhara H, Nika S, et al. Characteristic features of bdominal organ injuries associated with gastric rupture in blunt abdominal trauma. Am J Surg. 2004;187:394-397.

6 Bruscagin V, Coimbra R, Rasslan S, et al. Blunt gastric injury: a multicentre experience. Injury. 2001;32:761-764.

7 Nanji SA, Mock C. Gastric rupture resulting from blunt abdominal trauma and requiring gastric resection. J Trauma. 1999;47:410-412.

8 Ivatury RR, Simon RJ, Stahl WM. A critical evaluation of laparoscopy in penetrating abdominal trauma. J Trauma. 1993;34:827-828.

9 Zellweger R, Navsaria PH, Hess F, Omoshoro-Jones J, Kahn D, Nicol A. Transdiaphragmatic pleural lavage in penetrating thoracoabdominal trauma. Br J Surg. 2004;91:1619-1623.

10 Croce MA, Fabian TC, Patton JH, et al. Impact of stomach and colon injuries on intraabdominal abscess and the synergistic effect of hemorrhage and associated injury. J Trauma. 1998;45:649-655.

11 O’Neill PA, Kirton OC, Dresner LS, Tortella B, Kestner MM. Analysis of 162 colon injuries in patients with penetrating abdominal trauma: concomitant stomach injury results in a higher rate of infection. J Trauma. 2004;56:304-313.