CHAPTER 51 Gamma Knife® Radiosurgery for Convexity and Parasagittal Meningiomas

INTRODUCTION

Meningiomas arise from arachnoidal cap cells, and more than 90% of them are benign.1,2 As these tumors are encapsulated, complete resection is the preferred treatment. However; complete tumor resection is not always possible. Even if complete resection is successfully achieved, tumor recurrence is not uncommon during the long-term follow-up period. It has been reported that 20% to 30% of patients who had complete resection of their tumor, experienced recurrence in the follow-up period of 10 to 15 years.3–5 In cases of residual tumor, long-term tumor progression rates are higher, and tumor growth is demonstrated in 60% to 90% at follow-up of longer than 10 years.3–6 Therefore, in incompletely resected meningiomas, especially in atypical or anaplastic meningiomas, external-beam radiation therapy (EBRT) has been commonly performed, resulting in improved local tumor control.7–9 However, despite improved local tumor control, EBRT can cause long-term complications such as cognitive decline, pituitary insufficiency, or radiation-induced tumors. Recently, stereotactic radiosurgery has emerged as an alternative to EBRT or surgical resection and has gained more and more importance in the management of meningiomas, especially in those that cannot be completely resected, such as many skull-base meningiomas.

RADIOSURGICAL TECHNIQUES

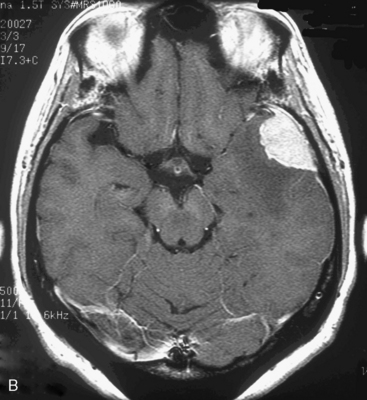

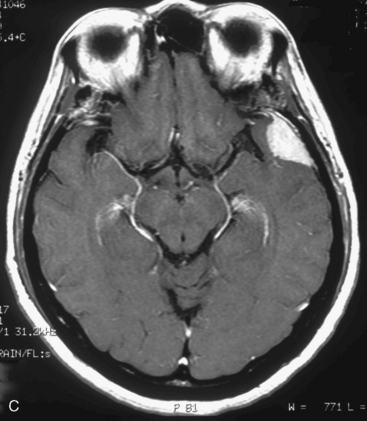

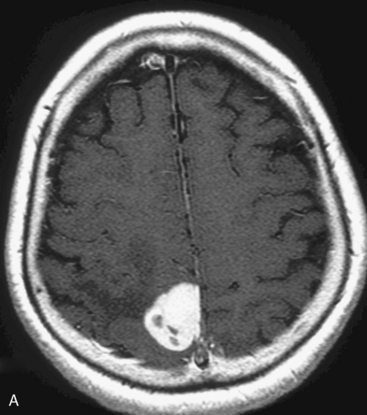

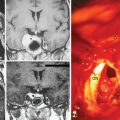

At our institute, Gamma Knife radiosurgery is performed using the Leksell stereotactic frame (Model G; Elekta Instruments, Sweden, AB). During Gamma Knife radiosurgery; first, the frame is applied to the patient under mild sedation and local anesthesia, then MRI or computed tomography (CT) scan is performed. Axial and coronal T1-weighted images with contrast enhancement are usually used for dose-planning. Patient treatment is planned using GammaPlan® software. After dose planning, GKRS is performed. Axial gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted MR images obtained in a 47-year-old woman, showing a left convexity meningioma, which has been treated in our institution with GKRS at a margin dose of 14 Gy (A), is presented in Figure 51-1. It is important to target the entire tumor, including the dural tail to achieve long-term tumor control, in the dose planning for meningiomas.

TUMOR CONTROL AND PREDICTIVE FACTORS

To date, numerous investigators have reported the results of stereotactic radiosurgery application to meningiomas in various locations, demonstrating 75% to 100% local tumor control rates at 5 to 10 years.2,10–25 To the best of our knowledge, there are only few large studies focusing on superficially located meningiomas treated alone with stereotactic radiosurgery, as most neurosurgeons prefer surgical resection to radiosurgery to treat this type of benign tumor. According to a multicenter review in 1998 by Kondziolka and colleagues,16 in 203 patients with parasagittal meningiomas, all patients were treated by GKRS and the actuarial 5-year tumor control rates were 93% ± 4% and 60% ± 10% in the primary and adjuvant treatment group, respectively. None of the patients having tumors smaller than 7.5 cm3, and no prior open surgery, required additional therapy and their neurologic function have remained stable. The authors also insisted that most treatment failures resulted from remote tumor growth. The rate of transient, symptomatic edema after GKRS was 16% and this complication was more common with larger tumors within 2 years. Kondziolka and colleagues32 reported 972 patients with intracranial meningiomas, and 239 meningiomas were located at the parasagittal region and convexity. The morbidity rate for the parasagittal location was 9.7%. Kollova and colleagues2 reported the treatment results of 368 patients who had benign meningiomas in various locations with a median follow-up of 60 months. They demonstrated an actuarial 5-year tumor control rate of 98% and a postradiosurgical peritumoral edema rate of 15%. They found that treatment failures significantly occurred in men and in tumors treated at a marginal dose of less than 12 Gy. Significant risk factors for postradiosurgical edema were patient age older than 60 years, no prior surgery, prelesional edema before radiosurgery, tumor volume greater than 10 cm3, tumor location in the anterior fossa, and a marginal dose of greater than 16 Gy. Kim and colleagues15 found postradiosurgical symptomatic edema in 43% of superficially located meningiomas. They documented that parasagittal lesions had a tendency to severe postradiosurgical edema. Chang and colleagues1 found in their meningioma series of 179 patients that convexity, parasagittal and falx meningiomas that were deeply embedded in the cortex developed postradiosurgical edema more frequently and tumor location was the only risk factor for it. Approximately 60% of patients who had postradiosurgical edema were asymptomatic and their symptoms were all transient. Postradiosurgical edema was found in four of 79 skull-base meningiomas (5%), compared with 26 of 52 hemispheric meningiomas (50%). Kalapurakal and colleagues26 suggested that parasagittal location, presence of pretreatment edema, and sagittal sinus occlusion were significant predictors for the development of brain edema after stereotactic radiosurgery and radiation therapy. They noted that all of the patients who developed severe posttreatment life-threatening panhemispheric edema had parasagittal meningiomas.

Concerning atypical and anaplastic meningiomas, it is difficult to achieve long-term tumor control even with relatively high-dose radiosurgery. Harris and colleagues27 reported 30 patients who were treated with GKRS including 18 atypical and 12 anaplastic meningiomas. The actuarial 5-year overall survival was 59% for both atypical and anaplastic meningiomas. The 5-year progression-free survival was 83% and 72% in patients with atypical and anaplastic meninigomas, respectively. They noted that early adjuvant radiosurgery after craniotomy was a significant factor for better progression-free survival. Similarly, Stafford and colleagues24 documented that the actuarial 5-year local tumor control rates were 68% and 0% for atypical and anaplastic meningiomas, respectively, compared with 93% for benign meningiomas.

Kobayashi and colleagues33 reported 87 cases of benign meningioma and showed a minimal size reduction of 16.1% and a response rate of 8.0%, but a higher control rate of 93%. Side effects were found in 12 cases (13.8%): radiation-induced edema in 9, hearing disturbance in 2, and visual deterioration in 1.

Hasegawa and colleagues13 reported long-term results of 111 patients with cavernous sinus meningiomas treated using GKRS. They demonstrated that the actuarial 5- or 10-year focal tumor control was 94% and 92%, respectively. Lee and colleagues17 also documented actuarial tumor control rates of 97.5% at both 5 and 10 years in 79 patients harboring cavernous sinus meningiomas. Although this difference may be caused simply by patient selection, superficially located meningiomas may be more radioresistant than skull-base meningiomas, as it has been demonstrated that a decrease in tumor volume occurs sooner after radiosurgery in skull-base meningiomas. Treatment failure tends to occur from the tumor margin or outside the treatment volume, because GKRS has a characteristic heterogeneous dose distribution, indicating that the radiation dose is highest at the center of the tumor and gradually decreases toward the tumor margin. In addition, it is sometimes difficult to differentiate the tumor margin from normal dural tissue or superior sagittal sinus, especially in cases of parasagittal lesions. This may lead to relatively lower tumor control rates compared with meningiomas in other locations. As a prognostic factor, prior surgery was significantly important for progression-free survival (PFS). This indicates that prior surgery makes production of a treatment plan more complicated, as it is hard to distinguish residual tumor from postoperative changes on enhanced MR images. Moreover, the residual tumor is often divided into multiple pieces after surgery. These issues lead to out-of-field treatment failure. Even though out-of-field treatment failure has occurred, repeat GKRS can be effectively and safely used to control the tumor. To avoid these types of treatment failures, a carefully prepared conformal plan, including the correct tumor margin within the treatment volume, is essential. Currently, in our institute multiple isocenters are usually used to make a more homogeneous and conformal plan with automatic positioning system, which helps us treat complicated lesions most efficiently. With regard to radiologic features associated with tumor recurrence, lobulated and mushrooming meningiomas are more aggressive, whereas smooth and calcified meningiomas generally tend to be less active.28,29

Optimum Radiosurgical Dose

Meningiomas are generally considered to be radioresistant. Compared to other tumors, most benign meningiomas remain stable or even become slightly smaller on the long-term follow-up images after radiosurgery. Several investigators have reported the efficacy of lower-dose radiosurgery for benign meningiomas to date. Kondziolka and colleagues16 noted that margin doses greater than 15 Gy did not provide better tumor control. Currently, in our institution we also decreased to a margin dose of 13 to 14 Gy in most cases. Irradiated dosage is limited by not only tumor volume but also by adjacent critical structures such as brain stem or cranial nerves, although this issue is rare in the cases of convexity or parasagittal meningiomas. For relatively large skull-base meningiomas adjacent to critical structures, lower-dose radiosurgery with a peripheral dose of 12 Gy or less may still be useful to prevent further tumor growth. Particularly in the cases of lesions which are adjacent or impinging on the optic apparatus, the marginal tumor dose should be reduced to 10 Gy or less to avoid optic neuropathy. However, further follow-up is necessary to determine whether low-dose radiosurgery with a margin dose of 14 Gy or less provide long-term tumor control.

Adverse Radiation Effect

Current evidence has shown that Gamma Knife radiosurgery is a safe treatment method for meningiomas. Numerous investigators reported that incidence of morbidity was less than 10% and the majority were transient. 2,13,16,17,19,24,30 However, parasagittal or convexity meningiomas are more likely to have postradiosurgical peritumoral brain edema than skull-base tumors. If postradiosurgical symptomatic edema occurs, a course of steroids should be administered. If no improvement can be achieved, an open surgery should be considered without hesitation.

According to a literature review by Rogers and Mehta,31 postradiosurgical edema developed in 25% to 78% of patients with non-basal meningiomas, compared with 0 to 22% of patients with skull-base meningiomas. The development of brain edema is considered to be associated with the impairment of the blood–brain barrier, vascular endothelial growth factor affecting vascular permeability, mass effect with brain ischemia, and impaired venous drainage.2 Parasagittal or convexity meningiomas have a broader pial interface and more pial blood supply than skull-base meningiomas surrounded by cistern. Accordingly, a larger volume of adjacent brain parenchyma is irradiated, and damaged, consequently leading to the development of postradiosurgical brain edema. In patients who had prior surgery, postradiosurgical edema is less common because the brain parenchyma is dissected from the tumor surface, disrupting the pial blood supply at the time of open surgery.2 Superior sagittal sinus or bridging vein occlusion may also contribute to the development of postradiosurgical edema. As other factors, higher marginal dose and larger tumor volume are also considered to cause a higher incidence of post-radiosurgical edema.

Management Strategy

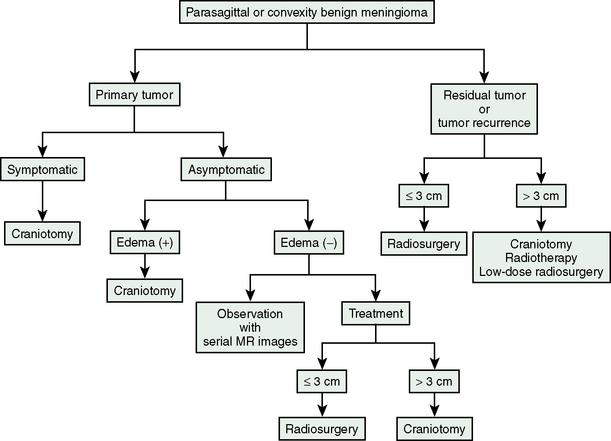

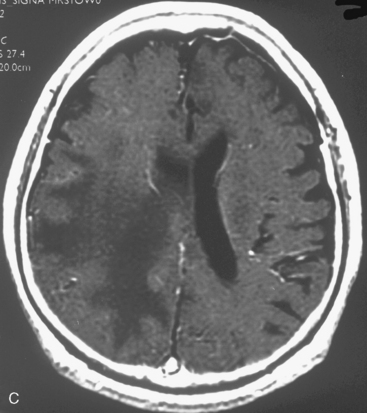

Current management strategy for meningiomas used in our institute is presented in Figure 51-2. The patients with tumor recurrence or residual tumor after open surgery are good candidates for GKRS. Particularly, tumors invading superior sagittal sinus should be treated using GKRS after removal of the tumor outside the tumor. Even when tumor size is relatively large with a mean diameter of 3 cm or more, low-dose radiosurgery may halt tumor growth. In patients harboring symptomatic tumors or tumors with peritumoral edema, we strongly recommend open surgery as the initial treatment. Parasagittal meningiomas with peritumoral edema should not be treated using stereotactic radiosurgery as the initial treatment; otherwise patients will develop severe postradiosurgical edema, eventually requiring surgical resection. Patients harboring asymptomatic tumors without peritumoral edema may be observed with serial imaging follow-up, or may select open surgery or radiosurgery depending on tumor size and location if patients provide informed consent, especially when further tumor growth would make the treatment more risky.

The role of radiosurgery in atypical and anaplastic meningiomas was also published in the literature. Recently Kondziolka and colleagues32 reported an overall control rate for all intracranial meningiomas. Patients with WHO grade I meningiomas had a control rate of 93%, but for patients with WHO grade II and III tumors, the control rates were 50% and 17%, respectively.

Kano and colleagues34 published findings on 12 patients with 30 atypical or anaplastic meningiomas. Patients separated in two groups with treatment dose of 20 Gy. Tumor control rate was 29,4% in the group treated with less than 20 Gy and 63.1% in the group treated with 20 Gy.

AUTHORS’ EXPERIENCE

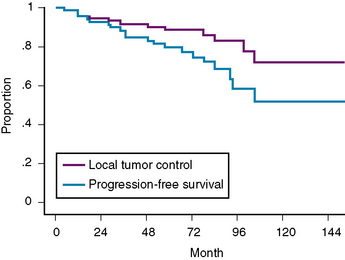

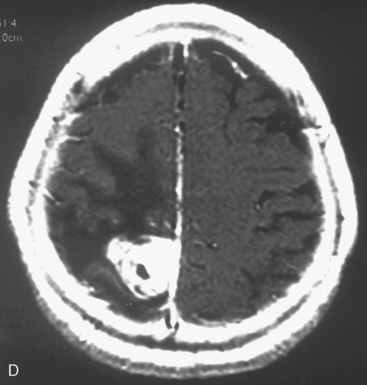

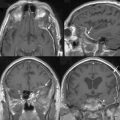

At our institution, we performed a retrospective study in 81 patients with 88 convexity, falx, or parasagittal benign meningiomas who were treated using GKRS between 1991 and 2002. Patient characteristics are shown in Table 51-1 and the tumor localization is indicated in Table 51-2. The actuarial 5- or 10-year PFS was 80% or 52%, respectively (Fig. 51-3). The actuarial 5- or 10-year local tumor control (LTC) was 89% or 72%, respectively. The factors affecting LTC or PFS rates were advanced patient age and having prior open surgery. No other factors were found to have a significant effect on PFS or LTC. On the follow-up radiological imaging, 17 patients (23%) developed peritumoral edema at 3 to 12 months after GKRS (Fig. 51-4). Seven patients had falx lesions, five had parasagittal lesions, three had cerebellar convexity lesions, and two had convexity lesions. Among them, four patients were symptomatic. Two patients developed motor weakness requiring surgical resection. One patient developed seizure caused by severe edema. Another patient died from severe peritumoral edema at 29 months after GKRS. No other adverse radiation effect was found during the follow-up period.

| Characteristics | Value |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 23–80 (mean 56) |

| Male : female (%) | 28 (35) : 53 (65) |

| Prior surgery (%) | |

| 0 | 30 (37) |

| 1 | 36 (44) |

| 2 | 12 (15) |

| 3 | 2 (2) |

| 4 | 1 (1) |

| Follow-up (months) | 4–182 (median 79) |

| Lost | 6 |

| ≥5 years (%) | 57 (76) |

| ≥10 years (%) | 15 (20) |

TABLE 51-2 Tumor location (N = 88)

| Location | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Parasagittal | 35 (40) |

| Falx | 34 (39) |

| Convexity | 13 (15) |

| Cerebellar convexity | 6 (7) |

CONCLUSIONS

[1] Chang J.H., Chang J.W., Choi J.Y., et al. Complications after gamma knife radiosurgery for benign meningiomas. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74:226-230.

[2] Kollova A., Liscak R., Novotny J., et al. Gamma Knife surgery for benign meningioma. J Neurosurg. 2007;107:325-336.

[3] Condra K., Buatti J., Mendenhall W., et al. Benign meningiomas: primary treatment selection affects survival. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997;39:427-436.

[4] Mirimanoff R.O., Dosoretz D.E., Linggood R.M., et al. Meningioma: analysis of recurrence and progression following neurosurgical resection. J Neurosurg. 1985;62:18-24.

[5] Stafford S.L., Perry A., Suma V.J., et al. Primarily resected meningiomas: Outcome and prognostic factors in 581 Mayo Clinic patients, 1978 through 1988. Mayo Clin Proc. 1998;73:936-942.

[6] Wara W.M., Sheline G.E., Newman H., et al. Radiation therapy of meningiomas. AJR Ther Nuel Med. 1975;123:453-458.

[7] Barbaro N.M., Gutin P.H., Wilson C.B., et al. Radiation therapy in the treatment of partially resected meningiomas. Neurosurgery. 1987;20:525-528.

[8] Miralbell R., Linggood R.M., de la Monte S., et al. The role of radiotherapy in the treatment of subtotally resected benign meningiomas. J Neurooncol. 1992;13:157-164.

[9] Taylor B.W.Jr, Marcus R.B.Jr, Friedman W.A., et al. The meningioma controversy: postoperative radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1988;15:299-304.

[10] Chuang C.C., Chang C.N., Tsang N.M., et al. Linear accelerator-based radiosugery in the management of skull base meningioma. J Neurooncol. 2004;66:241-249.

[11] DiBiase S.J., Kwok Y., Yovina S., et al. Factors predicting local tuomr control after gamma knife stereotactic radiosurgery for benign intracranial meningiomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;60:1515-1519.

[12] Flickinger J.C., Kondziolka D., Maitz A., et al. Gamma knife radiosurgery of imaging-diagnosed intracranial meningioma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;56:801-806.

[13] Hasegawa T., Kida Y., Yoshimoto M., et al. Long-term outcomes of Gamma Knife surgery for cavernous sinus meningiomas. J Neurosurg. 2007;107:745-751.

[14] Iwai Y., Yamanaka K., Ishiguro T. Gamma knife radiosurgery for treatment of cavernous sinus meningiomas. Neurosurgery. 2003;52:517-524.

[15] Kim D.G., Kim C.H., Chung H., et al. Gamma knife surgery of superficially located meningioma. J Neurosurg(Suppl). 2005;102:255-258.

[16] Kondziolka D., Flickinger J.C., Perez B. Judicious resection and/or radiosurgery for parasagittal meningiomas: outcomes from a multicenter review. Neurosurgery. 1998;43:405-414.

[17] Lee J.Y.K., Niranjan A., McInerney J., et al. Stereotactic radiosurgery providing long-term tumor control of cavernous sinus meningiomas. J Neurosurg. 2002;97:65-72.

[18] Nicolato A., Foroni R., Alessandrini F., et al. Radiosurgical treatment of cavernous sinus meningiomas: experience with 122 treated patients. Neurosurgery. 2002;51:1153-1161.

[19] Pollock B.E. Stereotactic radiosurgery for intracranial meningiomas: indications and results. Neurosurg Focus. 2003;14:E4.

[20] Roche P.H., Pellet W., Fuentes S., et al. Gamma knife radiosurgical management of petroclival meningiomas results and indications. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2003;145:883-888.

[21] Roche P.H., Regis J., Dufour H., et al. Gamma knife radiosurgery in the management of cavernous sinus meningiomas. J Neurosurg. 2000;93(Suppl. 3):68-73.

[22] Shin M., Kurita H., Sasaki T., et al. Analysis of treatment outcomes after stereotactic radiosurgery for cavernous sinus meningiomas. J Neurosurg. 2001;95:435-439.

[23] Spiegelmann R., Nissim O., Menhel J., et al. Linear accelerator radiosurgery for meningiomas in and around the cavernous sinus. Neurosurgery. 2002;51:1373-1380.

[24] Stafford S.L., Pollock B.E., Foote R.L., et al. Meningioma radiosurgery: tumor control, outcomes, and complications among 190 consecutive patients. Neurosurgery. 2001;49:1029-1038.

[25] Zachenhofer I., Wolfsberger S., Aichholzer M., et al. Gamma-Knife radiosurgery for cranial base meningiomas: experience of tumor control, clinical course, and morbidity in a follow-up of more than 8 years. Neurosurgery. 2006;58:28-36.

[26] Kalapurakal J.A., Silverman C.L., Akhtar N., et al. Intracranial meningiomas: factors influence the development of cerebral edema after stereotactic radiosurgery and radiation therapy. Radiology. 1997;204:461-465.

[27] Harris A.E., Lee J.Y.K., Omalu B., et al. The effect of radiosurgery during management of aggressive meningiomas. Surg Neurol. 2003;60:298-305.

[28] Nakasu S., Nakasu Y., Nakajima M., et al. Preoperative identification of meningiomas that are highly likely to recur. J Neurosurg. 1999;90:450-462.

[29] Niiro M., Yatsushiro K., Nakamura K., et al. Natural history of elderly patients with asymptomatic meningiomas. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000;68:25-28.

[30] Malik I., Rowe J.G., Walton L., et al. The use of stereotactic radiosurgery in the management of meningiomas. Br J Neurosurg. 2005;19:13-20.

[31] Rogers L., Mehta M. Role of radiation therapy in treating intracranial meningiomas. Neurosurg Focus. 2007;23:E4.

[32] Kondziolka D., Mathieu D., Lunsford L.D., et al. Radiosurgery as definitive management of intracranial meningiomas. Neurosurgery. 2008;62:53-58.

[33] Kobayashi T., Kida Y., Mori Y. Long-term results of stereotactic gamma radiosurgery of meningiomas. Surg Neurol. 2001;55:325-331.

[34] Kano H., Takahashi J.A., Katsuki T., et al. Stereotactic radiosurgery for atypical and anaplastic meningiomas. J Neurooncol. 2007;84:41-47.