Gallstone diseases and related disorders

Structure and function of the biliary system

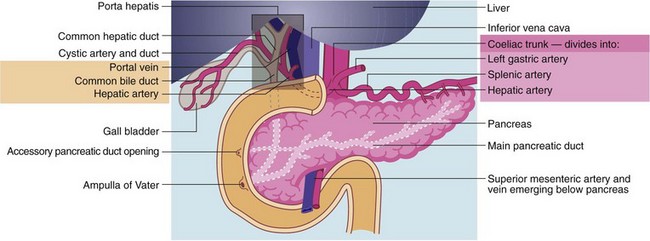

Bile collects in canaliculi between hepatocytes and drains via collecting ducts within the portal triads into a system of ducts within the liver. These progressively increase in diameter until they become the right and left hepatic ducts which fuse to form the common hepatic duct. This is joined further distally by the cystic duct to become the common bile duct (Fig. 20.1). The common bile duct is 4–5 cm long and passes down behind the duodenum then through the head of the pancreas to drain via the ampulla of Vater into the medial wall of the second part of the duodenum. In most cases, the main pancreatic duct joins the common bile duct at the ampulla although it may enter the duodenum independently. The sphincter of Oddi within the ampulla prevents reflux of duodenal contents into the common bile duct and pancreatic duct.

Fig. 20.1 Surgical anatomy of the gall bladder, biliary tract and pancreas

The coeliac trunk (the foregut artery) arises from the aorta and divides into the hepatic, splenic and left gastric arteries. The hepatic artery divides into right and left branches, mirrored by the extrahepatic right and left hepatic ducts. These join caudally to form the common hepatic duct; this in turn is joined by the cystic duct to form the common bile duct (CBD). The porta hepatis consists of the hepatic arteries, the extrahepatic bile ducts and the portal vein

Pathophysiology of the biliary system

Gallstone composition

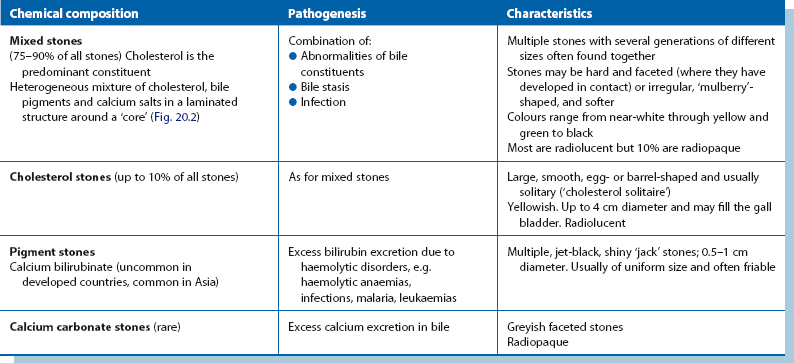

In developed countries, most gallstones are of mixed composition and contain a predominance of cholesterol; this is mixed with some bile pigment (calcium bilirubinate) and other calcium salts. A small proportion is virtually ‘pure’ cholesterol stones (‘cholesterol solitaire’). In Asia, most gallstones are composed of bile pigment alone. The composition and pathogenesis of the various types of gallstone are summarised in Table 20.1 (and see Fig. 20.2), and some examples are illustrated in Figure 20.3.

Fig. 20.2 X-ray of radiopaque gallstone

Plain abdominal X-ray showing large radiopaque gallstone in the right upper quadrant. Note that the stone is obviously laminated, having built up in layers over many years. Note also that only 10% of mixed stones are radiopaque

Fig. 20.3 Types of gallstone

(a) Thick-walled chronically inflamed gall bladder found to be obstructed at its neck by a single stone. Note the stone is an aggregate of many smaller stones

(b) Multiple small gallstones in the gall bladder, all of much the same ‘generation’.

(c) Gall bladder containing one huge stone and multiple smaller stones. These stones all fitted together with adjoining facets.

(d) Different types of gallstones—pale irregular stones of different ages on the left and a pigment ‘jack’ stone on the right

Investigation of gall bladder pathology

When gallstone disease is suspected, investigation has the following objectives:

• Exclude haematological and liver abnormalities and other metabolic disorders

• Establish if gallstones are present in the gall bladder and/or common duct and whether the gall bladder wall is thickened

• Assess the integrity and patency of the bile duct system and the pancreatic duct (if there is any suggestion of obstruction)

Blood tests for haematological and liver abnormalities: Haemolytic disorders such as hereditary spherocytosis, thalassaemia and sickle-cell trait should be considered as they may predispose to pigment stones. Liver function tests (LFTs) are indicated to look for indications of common duct stone obstruction if there is any suggestion of jaundice and to exclude other liver abnormalities.

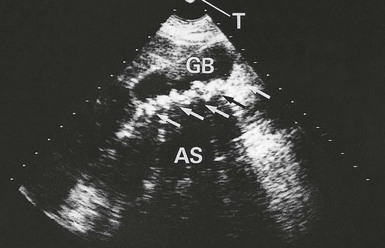

Imaging in investigating gall bladder pathology: Ultrasonography (see Fig. 20.4) can reliably identify stones in the gall bladder and any increase in thickness of the wall (caused by inflammation or fibrosis). Ultrasound also provides a simple and accurate means of demonstrating dilatation of the common duct system, often indicating distal duct obstruction. Unfortunately, it is unreliable for directly identifying bile duct stones, particularly at the lower end, because the image tends to be obscured by overlying duodenal gas. Ultrasound has the great advantage of being suitable for use in the seriously ill or jaundiced patient as it is non-invasive and can be performed at the bedside.

Fig. 20.4 Biliary ultrasound scans

Longitudinal scan of gall bladder in a 46-year-old woman who complained of intermittent attacks of right upper quadrant pain. The scan shows the outline of the gall bladder GB and a layer of gallstones (arrowed) along its posterior wall. The stones each cast a clear acoustic shadow AS beyond them. Note that these shadows can be projected back to the transducer T

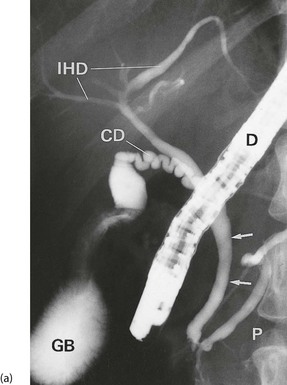

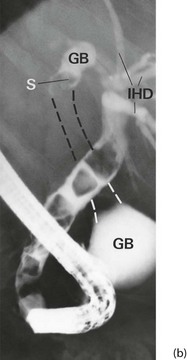

Investigating the biliary duct system: See Figure 20.5.

Fig. 20.5 Investigation of the biliary duct system

(a) Normal ERCP showing duodenoscope D in the second part of the duodenum. Contrast has been injected first into the pancreatic duct P and then into the common bile duct (arrowed). Note also the cystic duct CD, gall bladder GB and intrahepatic bile ducts IHD.

(b) Endoscopic retrograde cholangiogram in a woman of 77 who presented with mild epigastric pain and obstructive jaundice. The film shows multiple large stones in the common bile duct, represented by filling defects. The common bile duct is moderately dilated, but the intrahepatic ducts IHD are not. The fundus and neck of the gall bladder GB are shown, but the body is empty of contrast (dotted lines). There is a stone S near the neck of the gall bladder

The jaundiced patient

Ultrasound may make the diagnosis, but if more information is required, biliary tract morphology can be outlined using magnetic resonance cholangio-pancreatography (MRCP) which produces images of the biliary tree and pancreatic ducts (see Ch 5, p. 65; Fig. 5.6). If MRCP does not yield the necessary information, the ducts can be visualised by direct introduction of contrast. There are two methods: ERCP and, more rarely, percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography. ERCP is the more useful investigation; it also allows the ampullary region to be inspected for tumour. If stones are found in the common bile duct, it is often possible to perform immediate endoscopic sphincterotomy to release the stones, thus diagnosing and relieving the jaundice in one procedure. This may be life-saving for the patient with ascending cholangitis and is the treatment of choice on its own for the patient who is a poor risk for laparotomy or laparoscopy.

Percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (Ch 5, p. 65; Fig. 5.6) is used in exceptional circumstances, for example if ERCP is unsuccessful because of previous gastric surgery. It involves inserting a long, fine (22 gauge) needle through the skin into one of the dilated intrahepatic ducts under radiological control. Contrast medium is then injected. An obstructing stone produces a characteristic rounded filling defect, contrasting with the tapering stricture typical of tumour.

Clinical presentations of gallstone disease

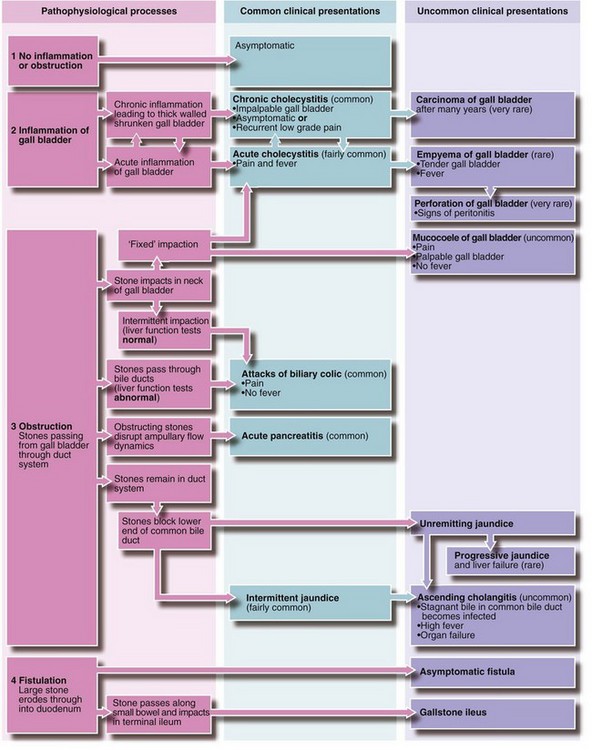

Rarely, free perforation of the gall bladder may occur. Equally rarely, large stones in the common bile duct ulcerate directly into the duodenum causing fistula formation. If they pass down the small bowel and impact in the terminal ileum and cause obstruction, this is called gallstone ileus. Finally, gallstones probably predispose to carcinoma of the gall bladder in the very long term. The spectrum of clinical disorders associated with gallstones is summarised in Figure 20.6.

Biliary colic

Management

Cholecystectomy is the definitive treatment for attacks of biliary colic. Patients are frequently put on a low-fat diet initially or whilst awaiting operation and this often relieves symptoms, presumably by removing a stimulus to gall bladder contraction. In younger patients, cholecystectomy is typically straightforward. The gall bladder is usually found to contain stones or thick dark biliary sludge and its wall is often thin, although it may sometimes be inflamed. In some patients, the gall bladder is thickened and scarred and technically more difficult to remove. Techniques of cholecystectomy are discussed on pages 290 onwards.

Cholecysto-duodenal fistula and gallstone ileus

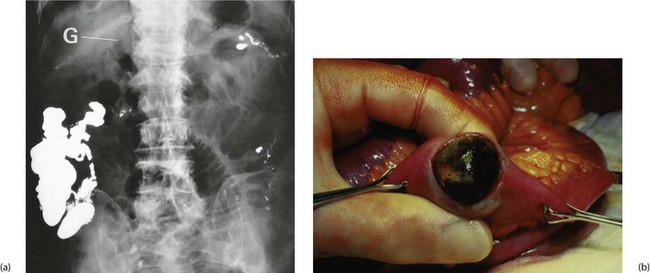

These uncommon complications of gallstones occur when the inflamed gall bladder becomes adherent to the adjacent duodenum and a stone ulcerates through the wall to form a cholecysto-duodenal fistula. The fistula decompresses the obstructed gall bladder and allows stones to pass into the bowel and gas to enter the biliary tree. The condition is usually painless and unsuspected but may be diagnosed on plain abdominal X-ray by the presence of gas outlining the biliary tree (see Fig. 20.7). Sometimes a fistula is discovered at operation.

Occasionally, a solitary cholesterol stone passing into the bowel is so large that after traversing the small bowel it impacts in the narrowest part, the distal ileum, causing small bowel obstruction or gallstone ileus (see Fig. 20.7). This occurs in the elderly and presents as an unexplained intermittent and sometimes incomplete small bowel obstruction. Unfortunately, the diagnosis is often difficult to make as the stone is usually radiolucent so in an elderly patient with distal small bowel obstruction, the diagnosis needs to be considered and can be confidently made if gas is recognised in the biliary tree on a plain abdominal X-ray.

Bile duct stones

Initially, stones in the bile ducts are small but if they stay in the bile duct without passing, they may enlarge progressively in situ. This is evident from the occasional finding of multiple faceted gallstones fitting neatly together in the common duct and which could only have formed within the duct. The common bile duct is narrowest at its lower end and stones too large to pass out tend to lodge there. Such a stone becomes impacted, causing progressive jaundice, or acts as a ball-valve, causing intermittent jaundice. Obstruction results in gradual dilatation of the biliary tree; longstanding dilatation does not regress even after the obstruction is removed and may lead to stagnation of bile and further stone formation. Note that the gall bladder rarely distends in this condition even when the common bile duct is completely obstructed, because of the inflammatory fibrosis or mural hypertrophy caused by gallstones (Courvoisier’s law—see Ch. 18, p. 259).

Clinical presentations of stones in the biliary tract

Obstructive jaundice: Stones in the common bile duct, as stated earlier, are a common cause of obstructive jaundice and must be considered in the differential diagnosis; details are given in Chapter 18.

Asymptomatic duct stones: Any patient with gallstones may have duct stones although asymptomatic duct stones are rare. Standard practice used to be to perform operative cholangiography at every operation. However, most surgeons now perform selective cholangiography in patients with signs, symptoms or investigations suggesting passage of stones.

Acute pancreatitis: Stones passing through or lying near the ampulla of Vater may interfere with drainage of pancreatic enzymes into the duodenum. Bile reflux into the main pancreatic duct may then cause acute pancreatitis (see Ch. 25).

Ascending cholangitis: Bile stasis in the common duct occurs with chronic obstruction and dilatation and predisposes to bacterial infection. The condition is known as ascending cholangitis and is a potent cause of systemic sepsis. It is characterised by intermittent attacks of pain, swinging pyrexia and jaundice. This triad is referred to as Charcot’s intermittent hepatic fever and is often accompanied by marked weight loss. Ascending cholangitis is a serious condition and may culminate in life-threatening acute suppurative cholangitis. The bile duct must be drained urgently, either by surgical operation or preferably by endoscopic sphincterotomy.

Management of gallstone disease

Non-surgical treatment of gallstones

• Only small—less than 1 cm—cholesterol-predominant stones can be dissolved

• High rate of stone recurrence after successful treatment—up to 50% after 2 years

• Frequent drug-related side-effects, e.g. severe diarrhoea and hepatic damage

For these reasons, drug therapy has largely gone out of favour and should only be considered in patients unfit for general anaesthesia with small radiolucent stones in a gall bladder which concentrates contrast and contracts in response to a fatty meal.

Surgical management of gallstones

Indications for surgery and preparation of the patient

There are two main indications for cholecystectomy:

• Symptomatic gallstone disease

• Asymptomatic gallstones when there is a reasonable likelihood of future symptoms or complications

In most cases high-quality biliary ultrasound is the only imaging study required. This demonstrates gall bladder disease and gallstones and the diameter of the intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts. Information from ultrasound about gall bladder wall thickness or the number and size of stones has not proved useful in predicting the feasibility of laparoscopic surgery. If there are stones in the duct system, common duct exploration is added to cholecystectomy or else stones are extracted at ERCP.

Any jaundiced patient is at particular risk during surgery because of infection, hepatic impairment, defective clotting, acute renal failure and venous thrombosis (see Table 18.2, p. 262). It is often preferable to relieve obstructive jaundice before surgery by endoscopic sphincterotomy and stone extraction or bile duct stenting to minimise some of these complications. In patients presenting with jaundice caused by operable carcinoma of the pancreas, however, the obstruction is often intentionally not relieved preoperatively because duct dilatation simplifies its anastomosis to bowel. It also minimises the risk of introducing infection into a stagnant biliary tree.

Cholecystectomy—open versus laparoscopic surgery

Laparoscopic management of gall bladder disease: Absolute contraindications to laparoscopic cholecystectomy include the late stages of pregnancy and uncorrected major bleeding disorders. Relative contraindications for less experienced surgical teams include morbid obesity, acute cholecystitis, untreated bile duct stones including obstructive jaundice, previous abdominal surgery (adhesions) and intra-abdominal malignancy.

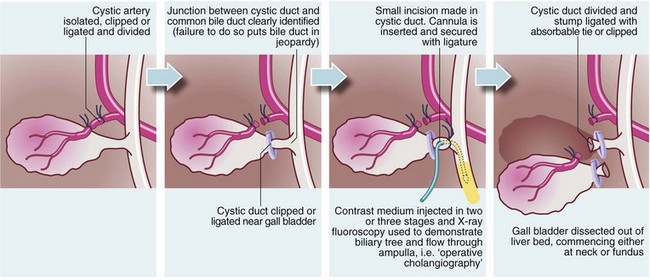

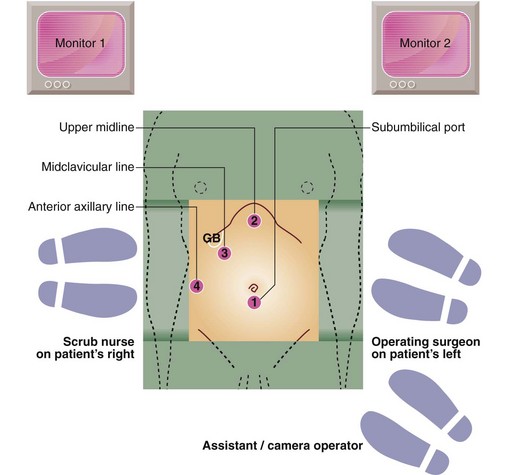

Operative technique: The main steps in cholecystectomy are shown in Figure 20.8 and a common operating theatre set-up for laparoscopic cholecystectomy is shown in Figure 20.9. The patient is anaesthetised and a pneumoperitoneum established via an open Hassan procedure using an automatic gas insufflator. The open method is very safe and has largely superseded the blind Veress needle technique. A 10 mm cannula is then placed into the abdomen to accommodate a video laparoscope and the abdominal cavity inspected for other pathology. Three additional abdominal punctures are usually made to introduce operating instruments. The cystic duct and artery are identified and an operative cholangiogram performed (if desired) percutaneously across the abdominal wall. It is extremely important to be certain of the ductal anatomy before cutting anything because of the distortion introduced by retraction of the gall bladder and the limitations of two-dimensional imaging systems. If in doubt, perform a cholangiogram.

Fig. 20.9 Operating theatre arrangement for laparoscopic cholecystectomy

A common arrangement of the various operating ports (numbered 1–4) is shown. The subumbilical port (1) is usually placed with the Hassan open technique to take a 10 mm video laparoscope. A Veress needle is still sometimes used for initial gas insufflation. At the upper midline port (2) a 10 mm trocar is placed 5 cm below the xiphoid under video vision to the right of the falciform ligament. This is used to introduce operating instrument—curved dissectors, clip applier, and suction and irrigation tubes. At the mid-clavicular (3) and anterior axillary (4) lines, 5 mm trocars give access for grasping forceps, which are used to retract the gall bladder, and liver retractors

Results of laparoscopic cholecystectomy: Most patients are able to walk and tolerate food within 6 hours of operation and up to 80% can be discharged within 24 hours. The intervals before return to work and other normal activities are significantly reduced compared with open cholecystectomy.

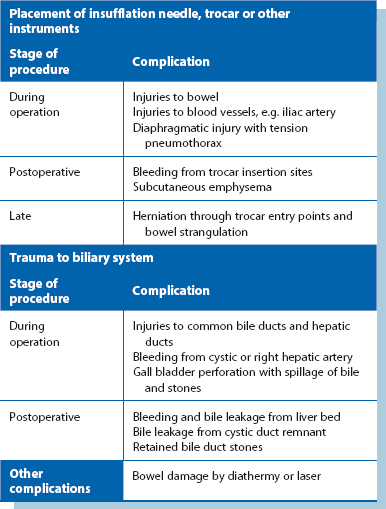

Bile duct injuries occur in approximately 0.5% of patients. The risk of bile duct injuries is undoubtedly related to the experience of the operating team but has been reported to be twice as high in laparoscopic surgery as open surgery. The consequences of bile duct injury can be catastrophic; patients have died with multi-organ failure resulting from unrecognised biliary peritonitis whilst others have required open operations to repair bile ducts and have risked the consequences of long-term bile duct strictures. Other potential complications are listed in Table 20.2.

Operations on the common bile duct

Exploration of the common bile duct: If stones are known to be present in the bile ducts, the common duct may be explored laparoscopically or at open surgery. The duct is opened through a longitudinal or transverse incision and stones retrieved by a combination of manipulation, irrigation, grasping with stone forceps or a Dormia basket or use of a balloon catheter. Operative choledochoscopy is often used to check for residual stones and to remove difficult stones. A flexible fibreoptic choledochoscope gives good visibility and manoeuvrability and can also be used in laparoscopic surgery. After exploration, a latex T-tube is usually inserted to drain bile to the exterior, with the transverse limb placed within the common bile duct. The main purpose of a T-tube is to provide access to the biliary tree for a further cholangiogram about 1 week after operation (T-tube cholangiography, see Fig. 20.10). This is to ensure that no stones remain and to allow any oedema at the ampulla to settle.

Endoscopic management of bile duct stones: With the widespread availability of ERCP and endoscopic sphincterotomy, stones in the common duct can often be retrieved without an operation. This technique represents a real advance in the management of duct stones over the earlier need for open surgery but does carry its own risks. Endoscopic sphincterotomy may be employed in the following circumstances:

• Urgent drainage of the bile duct in obstructive jaundice complicated by cholangitis. Definitive surgery can then be deferred until the risks of infection have been minimised

• Retrieval of stones missed at operation. This avoids a difficult and hazardous operation to explore or re-explore the duct

• Removal of duct stones in patients unfit for operation (gall bladder left in situ)

• Some cases of acute pancreatitis due to gallstones

• Preparation of a jaundiced patient for elective gall bladder surgery

Complications of biliary surgery

The procedure-specific complications of laparoscopic cholecystectomy are listed in Table 20.2. General complications of cholecystectomy are described below.

The retained stone: Despite considerable care at exploration of the common duct, stones occasionally remain in the duct system after operation and are revealed by postoperative T-tube cholangiography. Retained stones are usually retrieved by ERCP and sphincterotomy, although it is possible to retrieve retained stones percutaneously via a mature T-tube track using steerable grasping forceps or a Dormia basket.

Biliary peritonitis: Bile leaking into the peritoneal cavity is an irritant and causes a chemical peritonitis. If the bile is infected, it causes generalised peritonitis and sepsis with a high risk of fatality. Bile tends to leak through suture lines because of its detergent action. Therefore, whenever the duct system has been opened, a drain should be left in the vicinity for at least 5 days. Small leaks after biliary operations usually settle spontaneously but if biliary peritonitis develops, the area must be urgently drained percutaneously or, more often, re-explored surgically and drained, with intravenous antibiotic cover.

Bile duct damage: The bile ducts can easily be damaged at cholecystectomy or common duct exploration unless their anatomy, which is commonly aberrant, is carefully displayed. The most serious error is unrecognised transection or ligation of the common duct. This presents as a major biliary leak or increasing jaundice in which case, urgent re-exploration and reconstruction is mandatory. Lesser degrees of bile duct damage from crushing, overuse of diathermy or a careless ligature will heal but eventually cause a fibrotic stricture which presents much later with obstruction. Regardless of how the bile ducts are damaged, complex reconstructive surgery is usually required, often at a tertiary referral centre, although endoscopic placement of a long-term stent allows rescue of some strictured ducts without operation. In the medium term, however, stents inevitably become blocked and have to be replaced every 3–6 months.

Haemorrhage: The cystic and hepatic arteries and the vascular liver bed are vulnerable to operative trauma and bleed profusely. Removing a grossly inflamed or fibrotic gall bladder is particularly hazardous. Manoeuvres to control haemorrhage may damage other structures, passing unnoticed at the time; this is a common cause of bile duct trauma.

Hazards of pre-existing jaundice: These are discussed under Obstructive jaundice in Chapter 18 (p. 262).

Ascending cholangitis and other infections: Ascending cholangitis can be a late complication of biliary surgery where an anastomosis has been formed between bile ducts and bowel. Reflux of intestinal contents and organisms takes place continually in such cases but active infection only occurs when bile stagnates in the duct system because of inadequate drainage. Usually the diameter of the anastomosis has shrunk to a point when it no longer drains adequately. Ascending cholangitis may also occur early after common duct exploration for jaundice, since bile in this situation is nearly always infected. Prophylactic antibiotics should always be used when operating on jaundiced patients with duct obstruction to minimise this complication.