Gallbladder, liver, spleen and pancreas

7.3

Thickened gallbladder wall

> 3 mm – excluding the physiological, contracted (empty) gallbladder.

7.4

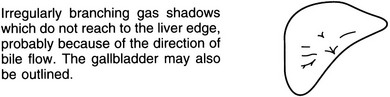

Gas in the biliary tract

Within the bile ducts

Spontaneous biliary fistula

Within the gallbladder

2. Emphysematous cholecystitis – due to gas-forming organisms and associated with diabetes in 20% of cases. There is intramural and intraluminal gas but, because there is usually cystic duct obstruction, gas is present in the bile ducts in only 20%. The erect film may show an air–bile interface.

7.5

Gas in the portal veins

1. Bowel infarction – the majority of patients die soon after gas is seen in the portal veins.

5. Air embolus during double-contrast barium enema – this has been observed during the examination of severely ulcerated colons and is not associated with a fatal outcome.

6. Acute gastric dilatation – in bed-ridden young people. May recover following decompression with a nasogastric tube.

7.8

Hepatic calcification

Curvilinear

1. Hydatid – liver is the commonest site of hydatid disease. Most cysts are in the right lobe and are clinically silent but may cause pain, a palpable mass or a thrill. 20–30% calcify and, although calcification does not necessarily indicate death of the parasite, extensive calcification favours an inactive cyst. Calcification of daughter cysts produces several rings of calcification.

2. Abscess – especially amoebic abscess when the right lobe is most frequently affected.

3. Calcified (porcelain) gallbladder – strong association with gallbladder carcinoma.

Localized in mass

1. Metastases – calcification is uncommon but colorectal and gastric carcinomas calcify most frequently. It may be amorphous, flaky, stippled or granular and solitary or multiple. Calcification may follow radiotherapy or chemotherapy.

2. Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma – usually small, centrally located and only visible on CT.

3. Adenoma – rare. Calcifications are punctate, stippled or granular. Often placed eccentrically within a complex heterogeneous mass.

7.10

Ultrasound liver – generalized hyperechoic

7.11

Ultrasound liver – focal hyperechoic

7.12

Ultrasound liver – focal hypoechoic

1. Metastasis – including cystic metastases (e.g. ovary, pancreas, stomach, colon).

3. Hepatocellular carcinoma – can be hypoechoic or hyperechoic.

4. Cysts – benign, hydatid. Hydatid cysts can be classified according to their sonographic pattern. Type I (commonest), uncomplicated unilocular cyst; Type II, a cyst with a split wall, i.e. a detached endocyst membrane; Type III, a cyst containing daughter cysts; Type IV, a cyst with a predominantly heterogeneous solid echo pattern with thick membranes and a few daughter cysts; Type V, a calcified cyst.

5. Abscess – ± hyperechoic wall due to fibrosis, ± surrounding hypoechoic rim due to oedema. Gas produces areas of very bright echoes.

7.17

CT liver – focal hyperdense lesion

Pre-intravenous contrast

7.18

CT liver – generalized low attenuation pre-intravenous contrast medium

1. Fatty infiltration – alcohol, obesity, early cirrhosis, parenteral feeding, bypass surgery, malnourishment, cystic fibrosis, steroids, Cushing’s syndrome, late pregnancy, carbon tetrachloride exposure, chemotherapy, high-dose tetracycline and glycogen storage disease. Unenhanced liver density 10 HU lower than spleen suggests the diagnosis.

(a) Acute – big, low-density liver with ascites. After intravenous contrast there is patchy enhancement of the hilum of the liver due to multiple collaterals, and non-visualization of the hepatic veins and/or IVC.

(b) Chronic – atrophied patchy low-density liver with sparing and hypertrophy of caudate lobe. Post-intravenous contrast scans show similar signs as the acute stage.

7.19

CT liver – generalized increase in attenuation pre-intravenous contrast medium

1. Haemochromatosis – may be an associated hepatoma present.

3. Iron overload – e.g. from large number of blood transfusions.

4. Glycogen storage disease – liver may be increased or decreased in density.

5. Amiodarone treatment – contains iodine. Can also cause pulmonary interstitial and alveolar infiltrates.

7.20

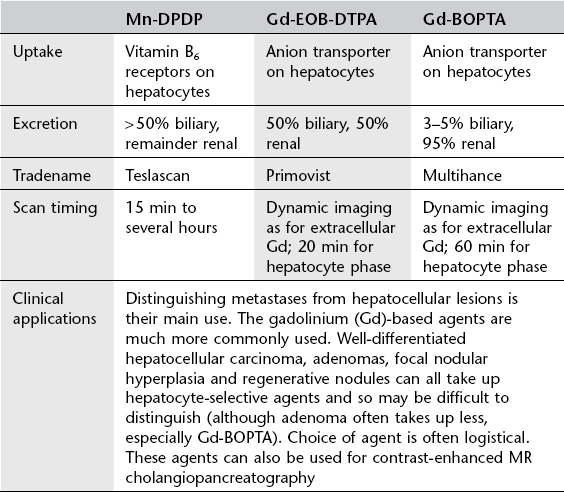

Liver-specific mri contrast media

Gandhi, S. N., Brown, M. A., Wong, J. G., et al. MR contrast agents for liver imaging: what, when, how. Radiographics. 2006; 26:1621–1636.

Seale, M. K., Catalano, O. A., Saini, S., et al. Hepatobiliary-specific MR contrast agents: role in imaging the liver and biliary tree. Radiographics. 2009; 29:1725–1748.

7.21

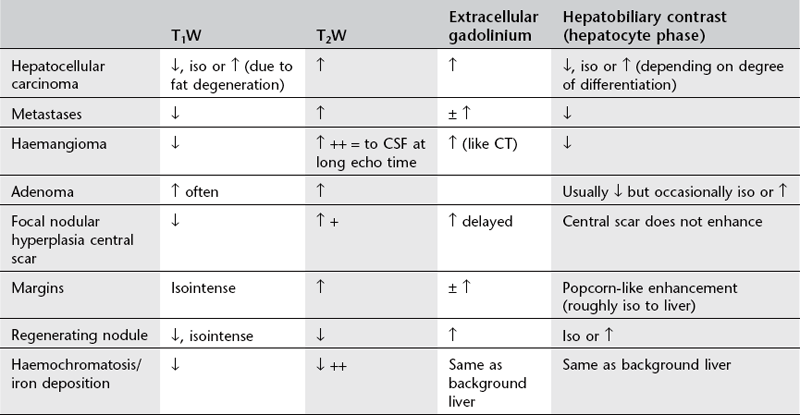

Mri liver

Fowler, K. J., Brown, J. J., Narra, V. R. Magnetic resonance imaging of focal liver lesions: approach to imaging diagnosis. Hepatology. 2011; 54(6):2227–2237.

Goodwin, M. D., Dobson, J. E., Sirlin, C. B., et al. Diagnostic challenges and pitfalls in MR imaging with hepatocyte-specific contrast agents. Radiographics. 2011; 31(6):1547–1568.

Silva, A. C., Evans, J. M., McCullough, A. E., et al. MR imaging of hypervascular liver masses: a review of current techniques. Radiographics. 2009; 29(2):385–402.

7.22

Mri liver – focal hyperintense lesion on T1W

NB. Most lesions are hypointense on T1W.

1. Fat – focal fatty deposits, adenoma, lipomas, angiomyolipomas, surgical defect packed with omental fat, occasionally hepatomas undergo fatty degeneration.

2. Blood – in the acute stage due to methaemoglobin.

3. Proteinaceous material – occurs in dependent layer of fluid–fluid levels in abscesses and haematomas due to increased concentration of hydrated protein molecules.

5. Chemical – gadolinium, lipiodol (contains fat).

6. ‘Relative’ – i.e. normal signal-intensity liver surrounded by low signal-intensity liver which may occur with iron deposition (haemochromatosis, i.v. iron therapy), cirrhosis (unclear aetiology, but a regenerating nodule within a cirrhotic area may appear artefactually hyperintense), oedema.

7. Artefact – pulsation artefact from abdominal aorta can produce a periodic ‘ghost’ artefact along the phase-encoded direction which can be hypointense or hyperintense depending on the phase.

7.23

Mri liver – ringed hepatic lesions

1. Capsules of primary liver tumours – a low-signal ring may be seen in 25–40% but does not differentiate between benign and malignant. A peritumoral halo of high signal on T2W is seen in 30% of primary tumours and more closely correlates with malignancy.

2. Metastases – halo of high signal on T2W or with central liquefaction to give an even higher centre and a ‘target’ lesion. A peritumoural halo or a target on T2W distinguishes metastasis from cavernous haemangioma.

3. Subacute haematoma – low-signal rim on T1W and T2W (because of iron) with an inner bright ring on T1W (because of methaemoglobin).

4. Hydatid cyst – T2W high-signal cyst contents with a low-signal capsule. The capsule is not well seen on T1W.

5. Amoebic abscess – prior to treatment incomplete concentric rings of variable intensity, better seen on T2W than T1W. During antibiotic treatment, T1W and T2W images show the development of four concentric zones because of central liquefaction and resolution of hepatic oedema.

7.24

Liver lesions with a central scar

7.25

Liver lesions causing capsular retraction

1. Metastases – particularly after treatment or with fibrotic tumours, e.g. breast, carcinoid, lung, colorectal.

2. Hepatocellular carcinoma – mainly the fibrolamellar type.

4. Cirrhosis – confluent hepatic fibrosis.

5. Following trauma – including iatrogenic, e.g. biliary drainage, biopsy, radiofrequency ablation.

7.26

Splenomegaly

7.27

Splenic calcification

7.28

Splenic lesion

Solid

2. Metastases – especially melanoma, lung and breast.

3. Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis.

5. Haemangioma – rare, but still the most common benign neoplasm of the spleen. Although the majority of patients are asymptomatic and are diagnosed incidentally, a 25% incidence of spontaneous rupture has been reported. Same US and CT characteristics as liver haemangioma.

Ahmed, S., Horton, K. M., Fishman, E. K. Splenic incidentalomas. Radiol Clin North Am. 2011; 49(2):323–347.

Bentre, T., Kluhs, L., Teichgraber, U. Sonography of the spleen. J Ultrasound Med. 2011; 30(9):1281–1293.

Elsayes, K. M., Narra, V. R., Mukundan, G., et al. MR imaging of the spleen: spectrum of abnormalities. Radiographics. 2005; 25(4):967–982.

7.29

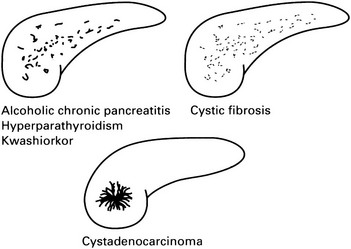

Pancreatic calcification

1. Alcoholic pancreatitis – calcification, which is almost exclusively due to intraductal calculi, is seen in 20–40% (compared with 2% of gallstone pancreatitis). Usually after 5–10 years of pain. Limited to head or tail in 25%. Rarely solitary. Calculi are numerous, irregular and generally small.

2. Pseudocyst – 12–20% exhibit calcification which is usually similar to that seen in chronic pancreatitis but may be curvilinear rim calcification.

3. Hyperparathyroidism* – pancreatitis occurs as a complication of hyperparathyroidism in 10% of cases. 70% have nephrocalcinosis or urolithiasis and this should suggest the diagnosis.

4. Cystic fibrosis* – calcification occurs late in the disease when there is advanced pancreatic fibrosis associated with diabetes mellitus. Calcification is typically finely granular.

5. Kwashiorkor – pancreatic lithiasis is a frequent finding and appears before adulthood. The pattern is similar to chronic alcoholic pancreatitis.

6. Hereditary pancreatitis – AD. 60% show calcification which is typically rounded and often larger than in other pancreatic diseases. 20% die from pancreatic malignancy. The diagnosis should be considered in young, non-alcoholic patients.

7. Tumours – for all practical purposes adenocarcinoma does not calcify. However, there is an increased incidence of pancreatic cancer in chronic pancreatitis and the two will be found concurrently in about 2% of cases. Conversely, calcification is observed in 10% of cystadenomas and cystadenocarcinomas. It is non-specific but occasionally ‘sunburst’.

Bashir, M. R., Gupta, R. T. MDCT evaluation of the pancreas: nuts and bolts. Radiol Clin North Am. 2012; 50(3):365–377.

Campisi, A., Brancatelli, G., Vullierme, M. P., et al. Are pancreatic calcifications specific for the diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis? A multidetector-row CT analysis. Clin Radiol. 2009; 64(9):903–911.

7.30

Cystic pancreatic lesion

2. Serous cystic neoplasm (serous cystadenoma) – usually females aged over 60, numerous subcentimetre cysts in a honeycomb or sponge-like pattern with a central scar which may calcify, benign. If not a pseudocyst, cystic lesions in the head of pancreas with non-enhancing walls of < 2 mm, a lobulated contour and no communication with the pancreatic duct are usually serous cystic neoplasms.

3. Mucinous cystic neoplasm (MCN) – usually women in early middle age, located in the body and tail. Unilocular or multilocular well-defined cyst, no communication with the ducts. Range from benign to malignant (mural nodularity, thick septa or calcification are sinister).

4. Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN) – commoner in men, communicates with the pancreatic ductal system. Main duct IPMN are 70% malignant, branch duct harbours malignancy in 15%. Enhancing solid components, main duct involvement, duct dilatation > 10 mm and size > 3.5 cm are concerning features.

5. Solid pseudopapillary neoplasm (SPN) – rare tumour of women in their thirties, usually in the tail. Benign or low-grade malignant. Mixed density with enhancing central papillae and a hypointense fibrous capsule on MRI.

6. True cyst – associated with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease, von Hippel–Lindau disease and cystic fibrosis.

7. Cystic metastases – especially renal cell, melanoma and lung carcinoma.

7.31

CT of pancreas – solid mass

1. Adenocarcinoma – 60% head, 15% body, 5% tail, 20% diffuse. 40% are isodense on precontrast scan, but most of these show reduced density on a postcontrast scan. Virtually never contain calcification. The presence of metastases (nodes, liver) or invasion around vascular structures (SMA, coeliac axis, portal and splenic vein) helps to distinguish this from focal pancreatitis.

2. Focal pancreatitis – usually in head of pancreas. Can contain calcification, but if not may be difficult to distinguish from carcinoma.

3. Metastasis – e.g. breast, lung, stomach, kidney, thyroid.

4. Islet cell tumour – equal incidence in head, body and tail. 80% are functioning and so will present at a relatively small size. 20% are non-functioning and so are larger and more frequently contain calcification at presentation. In general, functioning islet cell tumours, other than insulinomas, are often malignant, whereas 75% of non-functioning tumours are benign.

(i) Insulinoma – 90% benign, 10% multiple, 80% < 2 cm in diameter. Usually isodense with marked contrast enhancement. Can calcify.

(i) Gastrinoma – 60% malignant, 30% benign adenoma, 10% hyperplasia. 90% located in pancreas, 5% duodenum, occasionally stomach and splenic hilum. Shows marked contrast enhancement. Multiple adenomas seen as part of multiple endocrine neoplasia I syndrome (pituitary, parathyroid and pancreatic adenomas).

(ii) Glucagonoma – usually > 4 cm, since endocrine disturbance is often less marked.