Gait, coordination and abnormal movements

When examining gait and coordination, the results must be interpreted in the light of any motor or sensory findings in the rest of the examination. Patients with significant weakness or posterior column sensory loss will have some loss of coordination. There may be additional incoordination, and assessment of this is difficult and is based on a judgement as to whether the incoordination is disproportionate to the weakness or sensory loss.

Coordination

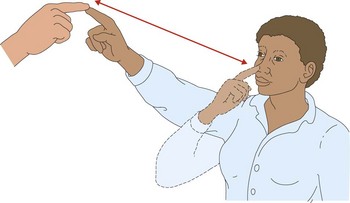

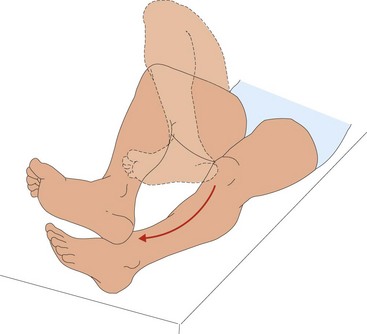

In testing coordination, look for smoothness and accuracy of movement. The standard manoeuvres used for bed-side testing are finger–nose coordination (Fig. 1), fast repeated movements and heel–shin testing (Fig. 2). Other parts of the examination afford an opportunity to observe coordination, for example the way the patient gets dressed and undressed and does up buttons.

Finger–nose coordination

Hold out your finger about 50 cm in front of the patient’s face. Ask the patient to touch your finger with his or her finger and then touch the nose. Ask the patient to repeat this (Fig. 1).

Heel–shin testing

Ask the patient to lift the heel up and put it on the opposite knee and then run it accurately down the front of the shin (Fig. 2).

Abnormal movements and posture

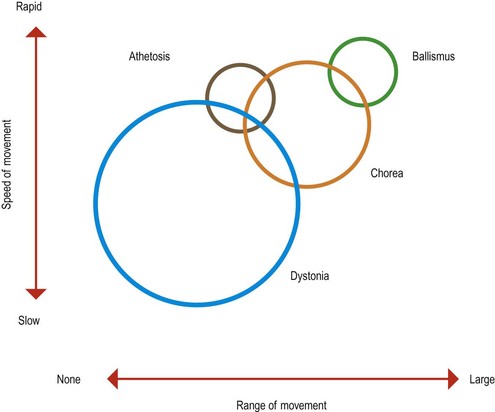

The diagnosis of patients with movement disorders is primarily syndromic and depends on the clinical classification of their movement disorder. There is considerable overlap between the movements and classification of some movements can be difficult, and in some patients this is a subject of dispute between experts (Fig. 3). However, the most common types of abnormal posture and movement are relatively easily identified.

Abnormal posture

The patient can have an abnormal posture as part of a generalized movement disorder, for example the stooped posture of a patient with Parkinson’s disease, with arms flexed and an immobile face. The abnormal posture may be the only abnormality, such as in focal dystonia where agonist and antagonist muscles co-contract and maintain an abnormal position. The most common focal dystonia is torticollis or cervical dystonia (p. 92).

Abnormal movements

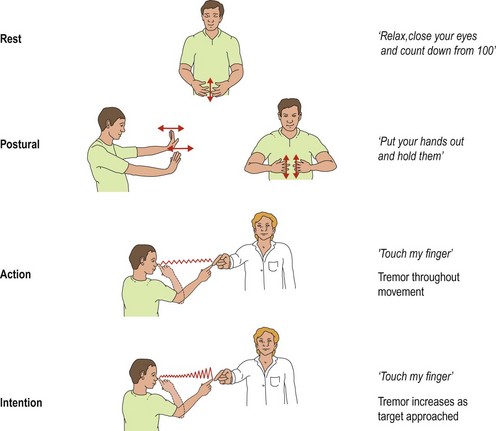

Tremor

Tremor is a rhythmical movement that can be described in terms of:

Some tremors have a particular character, such as the ‘pill-rolling’ tremor of Parkinson’s disease. Examination of tremor aims to distinguish these features. Observe patients at rest; they may need to be distracted to bring out the rest tremor – ask them to say the months of the year backwards or count down from 100. Ask the patient to hold the hands out in the positions (Fig. 4). Observe to see if the tremor develops (postural tremor). Test finger–nose coordination – the tremor can appear as the finger moves (action tremor) or increase as it gets closer to the target (intention tremor). Asking the patient to draw an Archimedes spiral (Fig. 5) is a useful way to document a tremor.

Rest tremor is commonly seen in extrapyramidal disease, and intention tremor as part of cerebellar syndromes (p. 63).

Dystonia, chorea, athetosis and ballismus

These abnormal movements have considerable overlap and can be usefully thought of as a spectrum rather than distinct entities (see Fig. 3).

Chorea is a fidgety, semi-purposeful movement that can vary in amplitude of movement and frequency of occurrence. Patients are often adept at hiding it by converting some of the abnormal movements into apparently intentional movements. Its causes are discussed on page 93.