CHAPTER 68 Fusion Surgery for Axial Neck Pain

INTRODUCTION

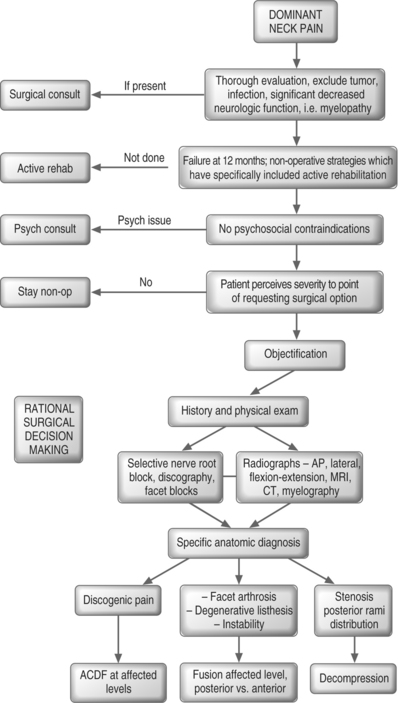

For those suffering from cervical radiculopathy or myelopathy, there is little debate that an anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (ACDF) is a viable treatment option.1–20 However, patients who present with their chief complaint being ‘neck pain,’ with or without referred or radicular symptoms, often are told that there is nothing that can be done surgically. This is wrong! The purpose of this chapter is to enhance the reader’s understanding of the surgical peer-reviewed literature, which leads to a rational decision-making process (Fig. 68.1). For many patients, that decision will be that surgical intervention is a reasonable option with a predictable statistical chance of success. The time-honored adage ‘that it is the decision, not the incision, which is most important,’ cannot be overemphasized.

INDICATIONS – PATIENT SELECTION

While covered in previous chapters, a brief review of the epidemiology and natural history of neck pain is in order. Prevalence studies have noted 35% of the general Norwegian population to have neck pain complaints within the preceding year, with 14% of respondents reporting those symptoms to have lasted longer than 6 months.21 In the Saskatchewan Health and Back Pain Survey, reported in 2000, it was documented that 54% of respondents had experienced neck pain in the preceding 6 months, with almost 5% perceiving themselves to be ‘highly disabled’ by their pain.22 When one looks at the literature of whiplash-associated disorders, it is apparent that while the majority of injured individuals do have spontaneous resolution of their symptoms, a small percentage, yet a significant number of human beings, do develop chronic neck pain.23,34

As with all medical ailments, it is important to appreciate the natural history of a condition. One approaches the patient with a ‘common cold’ with a vastly different sense of urgency than in comparison to an individual with suspected acute meningitis. We must then realize that in studies of natural history many with neck pain never seek out evaluation. Therefore, there is an inherent selection bias to more self-perceived impairment in those who seek out medical care. In an average 15.5-year follow-up study, Gore et al. reported on those presenting with neck pain.35 Seventy-nine percent of patients noted improvement with nonoperative care, with 43% reporting pain-free status and 32% continuing to report modest to severe pain. The severity of initial presenting symptoms, and the report of a significant injury, were more indicative of those with long-term complaints.

In a series of patients with neck-only, or neck and arm pain, DePalma et al. noted 45% of those treated nonoperatively to have satisfactory long-term outcome.36,37 In a surgical series report, DePalma et al. reported that at 3-month follow-up those presenting with dominant neck pain had 21% complete relief and 22% no relief with nonoperative care.36 At a 5-year follow-up time, Rothman noted 23% of patients continued to be partially or totally disabled due to significant cervical symptoms stemming from disc degeneration.36,38 In a review of those presenting with cervical radiculopathy, it was noted that while patients do not typically progress to myelopathy with nonoperative care, they often (two-thirds of the group) will have persistent symptomatology of some degree.39,40

The whiplash literature reveals a common pattern of a small group reporting persistent intrusive symptoms.23,34 In a textbook chapter, McNab and McCulloch summarized ‘about those who had suffered a whiplash injury, approximately 10–20% are left with discomfort of sufficient severity to interfere with their ability to do work and to enjoy themselves in leisure hours.’41 Thus, it must be acknowledged that while many who seek out medical care for neck pain will improve with nonoperative management, a finite low percentage of patients will still have symptoms of sufficient magnitude to cause them to seek out a surgical solution. It is for this group of patients that we need to have a rational surgical decision-making process.

OFFICE EVALUATION

History

When a patient presents for initial evaluation, we ask for their chief complaint, as this will focus our line of questioning and examination. In this chapter, we are concerned with those who complain of ‘axial neck pain.’ However, the typical patient does not say, ‘I have dominant axial pain;’ they state rather that they have neck pain, with or without arm pain. Patients who yield an ultimate diagnosis of myelopathy or radiculopathy will often present with a complaint of neck pain.8,40,42,43 It is up to the medical evaluation to elicit the historical features that will lead to a specific diagnosis.

I question about neurologic function. For myelopathy, I ask about generalized weakness, decreased fine motor dexterity, stumbling or ataxia, sphincter dysfunction such as urinary urgency, and paresthesias which may be nondermatomal. For radiculopathy, often a specific root pattern of numbness, pain, or specific weakness can be elicited. If these symptoms are present, they can help focus the differential to a specific cervical diagnosis. For psychosocial issues, we review the patient intake forms for depression, look for expectations of treatment, and solicit information about worker’s compensation status and litigation as these all may have a bearing on the patient-perceived pain. Specific psychologic treatment may be recommended. It is of interest that our last cervical fusion study did not correlate the presence of worker’s compensation or litigation with poor outcome.9

Physical examination

The physical examination should be straightforward. Range of motion is documented. If flexion hurts more than extension, think discogenic; if extension hurts more than flexion, think facet arthrosis or stenosis. If rotation or lateral flexion is preferentially limited to one side, it suggests a unilaterality of pathology. Spurling’s maneuver, i.e. lateral flexion, extension, and rotation which causes provocation of symptoms, suggests foraminal nerve root compression. If this reproduces the patient’s ‘neck pain,’ particularly into the upper trapezial or periscapular region, think nerve root pain. Assess the reflexes: hyperactive suggests upper motor neuron pathology, hypoactive suggests lower motor neuron pathology; and compare right side versus left side. Check for strength and sensation. If the examination documents pathology to suggest myelopathy or dense radiculopathy, the evaluation focuses on the neurologic deficit. An MRI or myelogram computed tomography (CT) scan should then be sought out. Often, those with dominant neck pain will have some component of arm symptomatology, just as those with ‘radiculopathy’ often have substantial complaints of neck pain.2,7,8,19,44,45

IMAGING

After a history is obtained and a physical examination is performed, one should start with basic radiographs. I prefer anteroposterior (AP), lateral, and flexion extension cervical spine radiographs. I do not routinely obtain an open mouth view or oblique views. One looks to exclude the obvious destruction of tumor and/or infection. We check for dynamic instability by the measurement of listhesis and angular deformity.43,46 We note obvious spondylosis by assessing disc space height, sclerosis, and osteophyte formation.47–49 While it is recognized that with increasing age there is an increasing presence of radiographic spondylosis, the films are helpful. If a young patient has multilevel spondylosis, we think less of a surgical approach; if a single level is involved, we think more of a surgical solution. If gross instability is seen, the patient needs to be counseled about the risks of nontreatment.

ADVANCED INVASIVE DIAGNOSTICS

Most often, the patient with axial pain will have several levels of degenerative change on an MRI study or noted on the X-rays. In those whose history and examination suggest a discogenic source, a discogram can be a very valuable tool. While the selection of this ‘older technology’ of discography still emotes controversy in some, I find it to be particularly useful in the surgical evaluation of those with axial pain. Data from our center has shown a statistical association with patient-perceived outcome.9 Numerous other authors have cited the utility of discography in patient selection.9,17,20,45,50–60

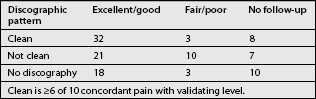

Most often, the MRI alone will not suffice. There are a substantial number of asymptomatic individuals who have MRI-documented pathology, which increases with age.60–63 In a prospective correlation of MRI and discography, in asymptomatic subjects and pain sufferers, Schellhas et al. concluded that MRI often misses annular tears and cannot reliably identify the source of discogenic pain.62 While many asymptomatic individuals had degenerative changes, only 3/40 discs studied in this group elicited a pain response, suggesting a high specificity and positive predictive value.62 Pragmatically speaking, the issue is, does the discogram yield information that reliably predicts outcome, and do published reports document this? The answer is yes, Table 68.1 documents such. What is hard to report upon is when the discogram keeps the patient out of surgery. For example, when every level hurts and there is no control, surgical intervention will not typically yield good results. The clean discographic surgical patient will have significant (greater than 6/10) concordant reproduction of pain at the affected level/levels, with little or no pain and normal appearance at the control level.9

| Author | Number of patients | Reported outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Zheng60 | 55 | 76% good or excellent, 18% fair, 6% poor |

| Garvey9 | 87 | 82% good or excellent, 16% fair, 2% poor |

| Ratliff54 | 20 | 85% satisfaction |

| Motimaya52 | 14 | 78.6% satisfaction |

| Palit53 | 38 | 79% satisfactory, 21% not satisfactory |

| Whitecloud19 | 34 | 70% good or excellent, 12% fair, 18% poor |

| Roth56 | 71 | 93% good or excellent, 1% fair, 6% poor |

| White46 | 28 | 62% good or excellent, 23% fair, 23% poor |

| Riley45 | 93 | 72% good or excellent, 18% fair, 10% poor |

| Simmons57 | 30 neck pain | 78% good or excellent, 15% fair, 7% poor |

| 51 neck and arm | ||

| William20 | 15 | 7% excellent, 20% good, 33% fair, 40% poor |

| Dohn50 | 34 | 62% good or excellent, 24% fair, 15% poor |

| Robinson17 | 56 | 73% good or excellent, 22% fair, 5% poor |

A selective nerve block can be useful in determining a surgical level. Such a patient may have neck, upper trapezial, and periscapular pain that increases with Spurling’s maneuver, has foraminal stenosis on MRI, and appears to have symptoms that are more often unilateral. In this patient, I often proceed to a selective nerve block. The selective nerve root block can be both diagnostic and potentially therapeutic. If in the first 30–60 minutes, during the lidocaine anesthetic phase, the patient reports significant diminution, i.e. 70–100% relief of typical pain, that specific nerve root is indicated as a primary pain generator. If steroids give long-term relief, all will be happy.64 If the patient has great relief with the selective nerve root block, unilateral pain, foraminal stenosis, and no instability, then a posterior laminoforaminotomy may be a favored option. If there is bilateral pain, and an additional ‘discogenic component,’ then one may proceed with an ACDF at the affected level.

True facet blocks or medial rami branch blocks are not uncommon in the work-up of patients with neck pain, particularly post-traumatic pain.24,65–68 To date, I know of no study to base fusion surgery on this diagnostic tool. Conceptually, one would think, if the patient had excellent temporary relief of the pain with this injection at a specific joint, that fusion of that joint may relieve the pain. If one were to use this intuitive reasoning to base the surgical decision, I would recommend that it be done in a study fashion with attendant IRB approval.

SURGICAL TREATMENT FOR SPECIFIC ANATOMIC DIAGNOSES

When the ultimate clinical diagnosis for a patient with chronic axial mechanical pain is that of discogenic pain, an anterior cervical discectomy and fusion is a very reasonable treatment option (Fig. 68.1). The patient will have symptoms of dominant neck pain with or without referred symptoms to the basioccipital region, upper trapezial region, or interscapular region. The patient may also have a component of arm pain with mild neurologic signs of dysfunction. The X-rays will often show spondylosis with no gross instability. The MRI and discography will pinpoint specific joints as the ‘painful levels.’ The more clean the diagnosis, i.e. one or two levels of concordant reproduction of pain, which matches the MRI appearance of degeneration, with a normal nonpainful adjacent segment, the higher is the likelihood that the patient will favorably respond to an anterior cervical decompression and fusion. Having more levels involved does not preclude the surgical option, but it does raise the risk of the patient reporting nonsuccessful outcome and pseudoarthrosis. Therefore, the patient needs to clearly understand this preoperatively. On the other hand, in an older population with advanced degeneration, these joints have less motion, and my experience has been favorable.9 The physiologically younger patient with expectation of high physical demand will be less satisfied with attempts at multilevel treatment.

To answer a patient’s question about what they may expect from surgical management, the reader needs to assess their level of satisfaction with the current surgical literature support for that treatment. A clever paper by Smith and Pell, titled ‘Parachute use to prevent death and major trauma related to gravitational challenge: systematic review of randomised controlled trials,’ points out that advocates of evidence-based medicine ought not to neglect the information we obtain from observational studies.69 When we see similar reports of good to excellent outcomes spanning six decades, from various centers, utilizing similar diagnostic evaluations and surgical interventions, we can place greater confidence in the predictability of those data (Table 68.1).9,17,20,45,50–58,60 The pioneers of ACDF surgery, Robinson and Smith, reported on 56 patients in their 1962 paper.16,17 Forty-five of 56 had neck pain, 38 of 56 had traumatic etiology, 25 of 56 had occipital pain, 26 of 58 had interscapular pain, and discography was done in 47 of 56 patients. They reported 73% good to excellent results, 22% fair, and 5.5% poor outcome, with 9 of 56 patients having pseudoarthrosis.

Highlighting the data from a recent series from our center can give an appreciation of what to expect from this type of surgical approach.9 Out of a prospective series of 112 patients with axial mechanical neck pain, 87 were available at average 4.4-year follow-up which included an extensive self-reported outcome data questionnaire. This series documented that 82% (71/87) self-rated their outcome to be good, very good, or excellent. Pain improvement was evidenced by an average diminution of the VAS from 8.4 preoperative to 3.8 at follow-up, and was seen in 93% of individuals. The average 3.8 follow-up score includes those with recurrent pain, new injury, and who did not respond, thus reflecting a higher average VAS. Self-rated function improved 50% as documented on both a cervical-modified Oswestry and Roland and Morris disability index. We specifically looked at our use of discography in the selection process (Table 68.2). If a clean anatomic pattern was present, that is greater than or equal to 6/10 concordant reproduction of pain, with little or no pain at an anatomically near-normal control level, and all of the affected levels were treated, 91% (32/35) reported good to excellent outcome. In those with ‘nonclean anatomic pattern,’ i.e. most commonly greater than or equal to 6/10 nonconcordant pain at what will become a proposed adjacent segment with mild to moderate morphologic abnormality, only 68% (21/31), reported good to excellent outcome. In the group where we did not utilize discography, i.e. those with single- or two-level pathology on MRI with a lesser component of clinically correlating radicular pain, 86% (18/21) self-reported good to excellent outcome. The take-home message is that the better one can objectify the pathology, the more likely is it that surgery can remedy the patient’s symptomatic complaints. The reader can review similar reports of surgical outcomes that span six decades from multiple centers (Table 68.1).9,17,20,45,50–58,60 These authors report remarkably similar outcomes and what appears to be a similar diagnostic grouping. This gives greater confidence that these studies do cumulatively support this type of surgical approach for discogenic neck pain.

Although the majority of my surgical practice for those with axial neck pain complaints is secondary to a discogenic etiology, a distinct group presents with complaints of neck pain, secondary to spondylosis, with facet arthrosis, facet ganglion cysts, rheumatoid arthritis, and/or instability as evidenced by degenerative listhesis. The caveat in this group is that a high percentage of radiographic spondylosis is seen in the asymptomatic population.47,69–71 In this group, one would potentially be a candidate either for an anterior decompression and fusion and/or a posterior cervical approach to specific joint pathology. This algorithmic breakout of ‘posterior-based’ pain would include those with rheumatoid arthritis who are more prone to subaxial instability. As noted earlier, if obvious arthrosis is seen at these joints, temporary relief is obtained with anesthetic blocks, treatment at these levels appears rational, but peer-reviewed validation is lacking.

Finally, a third group is seen in those with chief complaint of neck pain. These are the individuals with a radicular etiology, in whom a decompressive procedure would be indicated. Often, they will be more unilateral in their complaints. Upon more focused historical review, their pain will typically have more upper trapezial and periscapular radiation, on exam the symptoms will be typically made worse with Spurling’s maneuver, and the pain most often will be temporarily significantly reduced with a selective nerve root block. In this group, a posterior laminoforaminotomy with nerve root decompression is a rational surgical choice. They can also be managed with an anterior cervical decompression and fusion, but the fusion in this group may not be required. This posterior rami-based group also involves the upper cervical roots (C2, C3, and C4) which often have been neglected.42,72,73

SUMMARY

Patients who present with a chief complaint of chronic axial neck pain do have a surgical option available to them when nonoperative treatment, specifically including an active rehabilitative approach, has not yielded successful adequate resolution of the symptoms, and the patient feels that these symptoms are so severe that they would wish to entertain a surgical option with a typical 70–80% chance of good to excellent outcome. In this case, surgical diagnostic work-up should ensue. This includes the history and physical examination, radiographs, MRI or CT, and very often advanced diagnostic injections leading to objectification. In these patients, the rational surgical decision-making process will most often yield gratifying patient-perceived outcomes.

1 Bailey R, Badgely C. Stabilization of the cervical spine by anterior fusion. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1960;42(4):565-594.

2 Bohlman H, Emery S, Goodfellow D, et al. Robinson anterior cervical discectomy and arthrodesis for cervical radiculopathy. Long-term follow-up of 122 patients. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1993;75(9):1298-1307.

3 Cauthen J, Kinard R, Vogler J, et al. Outcome analysis of noninstrumented anterior cervical disectomy and interbody fusion in 348 patients. Spine. 1998;23:188-192.

4 Clements D, O’Leary P. Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion. Spine. 1990;15:1023-1025.

5 Cloward R. Cervical diskography technique, indications and use in diagnosis of ruptured cervical disks. Am J Roentgenol. 1958;79(4):563-574.

6 Dillin W, Booth R, Cuckler J, et al. Cervical radiculopathy. A review. Spine. 1986;11:988-991.

7 Emery S, Bolesta M, Banks M, et al. Robinson anterior cervical fusion: comparison of the standard and modified techniques. Spine. 1994;19(6):660-663.

8 Garvey T, Eismont F. Diagnosis and treatment of cervical radiculopathy and myelopathy. Orthop Rev. 1991;20(7):595-603.

9 Garvey T, Transfeldt E, Malcolm J, et al. Outcome of anterior cervical discectomy and fusion as perceived by patients treated for dominant axial-mechanical cervical spine pain. Spine. 2002;27:17.

10 Gore D, Sepic S. Anterior cervical fusion for degenerated or protruded discs: a review of 146 patients. Spine. 1984;9:667-671.

11 Herkowitz H. A comparison of anterior cervical fusion, cervical laminectomy and cervical laminoplasty for surgical management of multiple level spondylitic radiculopathy. Spine. 1988;13:774-780.

12 Light K, Simmons E. Simmons keystone anterior cervical discectomy and fusion. Surg Rounds Orthop. 1989;Oct:13-21.

13 Lunsford L, Bissonette D, Janetta P, et al. Anterior cervical surgery for cervical disc disease. Part I: Treatment of lateral cervical disc herniation in 253 cases. J Neurosurg. 1980;53:1-11.

14 Martin GJr, Haid R, MacMillan M, et al. Anterior cervical discectomy with freeze-dried fibula allograft. Spine. 1999;24:852-859.

15 Matwijecky C, Guyer R. Degenerative disorders of the cervical spine. Anterior microdiscectomy and multilevel anterior fusion. Spine: State of the Art Reviews. 1991;5(2):259-272.

16 Robinson R, Smith G. Anterolateral cervical disc removal and interbody fusion for cervical disc syndrome (abstract). Bull Johns Hopkins Hospital. 1955;96:223-224.

17 Robinson R, Walker E, Ferlic D, et al. The results of anterior interbody fusion of the cervical spine. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1962;44(8):1569-1587.

18 Smith G, Robinson R. The treatment of certain cervical-spine disorders by anterior removal of the intervertebral disc and interbody fusion. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1958;40(3):607-624.

19 Whitecloud T. Management of radiculopathy and myelopathy by the anterior approach. In: The Cervical Spine Research Society, editor. The Cervical Spine. 2nd edn. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott; 1989:644-658.

20 William J, Allen M, Harkess J. Late results of cervical discectomy and interbody fusion. Some factors influencing the results. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1968;50:277-286.

21 Bovim G, Schrader H, Sand T. Neck pain in the general population. Spine. 1994;19(12):1307-1309.

22 Cote P, Cassidy J, Carroll L. The factors associated with neck pain and its related disability in the Saskatchewan population. Spine. 2000;25(9):1109-1117.

23 Bannister G, Gargan M. Prognosis of whiplash injuries: a review of the literature. Spine: State of the Art Reviews. 1993;7(3):557-569.

24 Barnsley L, Lord S, Wallis B, et al. The prevalence of chronic cervical zygapopyhsial joint pain after whiplash. Spine. 1995;20(1):20-26.

25 Carroll C, McAfee P, Riley L. Objective findings for diagnosis of ‘whiplash.’. J Musculoskeletal Med. 1986;57:76.

26 Gargan M, Bannister G. Long-term prognosis of soft-tissue injuries of the neck. J Bone Joint Surg [Br]. 1990;72(5):901-903.

27 Hildingsson C, Toolanen G. Outcome after soft-tissue injury of the cervical spine. A prospective study of 93 car accident victims. Acta Orthop Scand. 1990;61:357-359.

28 Hohl M. Soft-tissue injuries of the neck in automobile accidents. Factors influencing prognosis. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1974;56(8):1675-1682.

29 Jonsson H, Cesarini K, Sahlstedt B, et al. Findings and outcome in whiplash-type neck distortions. Spine. 1994;19(24):2733-2743.

30 MacNab I. The ‘whiplash syndrome.’. Orthop Clin N Am. 1971;2:389-403.

31 Quebec Task Force on Whiplash-Associated Disorders. Scientific monograph of the Quebec Task Force on Whiplash-Associated Disorders. Spine. 1995;20(8S):3s-73s.

32 Shapiro A, Roth R. The effect of litigation on recovery from whiplash. Spine: State of the Art Reviews. 1993;7(3):531-556.

33 Teasell R. The clinical picture of whiplash injuries: an overview. Spine: State of the Art Reviews. 1993;7(3):373-390.

34 Watkinson A, Gargan M. Prognostic factors in soft tissue injuries of the cervical spine. Injury. 1991;23:307-309.

35 Gore D, Sepic S, Gardner G, et al. Neck pain: a long term follow-up of 205 patients. Spine. 1987;12:1-5.

36 DePalma A, Rothman R, Lewinnek G, et al. Anterior interbody fusion for severe cervical degeneration. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1972;134:755-758.

37 DePalma A, Subin D. Study of the cervical syndrome. Clin Orthop. 1965;38:135-141.

38 Rothman R. The spine, 2nd edn., Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1982:477.

39 Dillin W, Watkins R. Cervical myelopathy and cervical radiculopathy. Sem Spine Surg. 1989;4:200-208.

40 Lees F, Turner J. Natural history and prognosis of cervical spondylosis. Br Med J. 1963;2:1607-1610.

41 MacNab I, McCulloch J. Neck ache and shoulder pain. Chapter 6. In: Whiplash injuries of the cervical spine. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins; 1994.

42 Jenis L, An H. Neck pain secondary to radiculopathy of the fourth cervical root: an analysis of 12 surgically treated patients. J Spinal Disord. 2000;13:345-349.

43 Woiciechowsky C, Thomale UW, Kroppenstedt S. Degenerative spondylolisthesis of the cervical spine – symptoms and surgical strategies depending on disease progress. Euro Spine J. 2004;13(8):680-684.

44 Green P. Anterior cervical fusion: a review of 33 patients with cervical disc degeneration. J Bone Joint Surg [Br]. 1977;59:236-240.

45 Riley L, Robinson R, Johnson K, et al. The results of anterior interbody fusion of the cervical spine. J Neurosurg. 1969;30:127-133.

46 White A, Southwick W, Panjabi M. Clinical instability in the lower cervical spine. Spine. 1976;1:15-27.

47 Gore D, Sepic S, Gardner G. Roentgenographic findings of the cervical spine in asymptomatic people. Spine. 1986;11:521-524.

48 Johnson T, Steinbach L. Essentials of musculoskeletal imaging. Rosemount, IL: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons and American Academy of Pediatrics;. 2004:717-721.

49 Phipps M, Garvey T, Schwender J, et al. Cervical degeneration, neck pain and functional disability outcomes after long fusion to the sacrum: long-term follow-up. In: Cervical Spine Research Society, 32nd Annual Meeting; 2004; Boston, MA.

50 Dohn D. Anterior interbody fusion for treatment of cervical-disk condition. JAMA. 1966;197(11):897-900.

51 Garvey T, Transfeldt E, Malcolm J, et al. ACDF for neck pain: clinical outcome study. In: Cervical Spine Research Society 27th Annual Meeting; 1999 December 16–18, 1999; Seattle, Washington; 1999:24.

52 Motimaya A, Arici M, George D, et al. Diagnostic value of cervical discography in the management of cervical discogenic pain. Conn Med. 2000;64(7):395-398.

53 Palit M, Schofferman J, Goldthwaite N, et al. Anterior discectomy and fusion for the management of neck pain. Spine. 1999;24(21):2224-2228.

54 Ratliff J, Voorhies R. Outcome study of surgical treatment for axial neck pain. South Med J. 2001;94(6):595-602.

55 Riley L. Various pain syndromes which may result from osteoarthritis of the cervical spine. Maryland State Med J. 1969;18:103-105.

56 Roth D. A new test for the definitive diagnosis of the painful-disk syndrome. JAMA. 1976;235(16):1713-1714.

57 Simmons E, Bhalla S, Butt W. Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion. A clinical and biomechanical study with eight-year follow-up. With a note on discography: technique and interpretation of results. J Bone Joint Surg [Br]. 1969;51:225-237.

58 Whitecloud T, Seago R. Cervical discogenic syndrome. Results of operative intervention in patients with positive discography. Spine. 1987;12(4):313-316.

59 Zeidman S, Thompson K. Cervical discography. In: The Cervical Spine Research Society, editor. The Cervical Spine. 3rd edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1998:205-216.

60 Zheng Y, Liew S, Simmons E. Value of magnetic resonance imaging and discography in determining the level of cervical discectomy and fusion. Spine. 2004;29:2140-2145.

61 Boden S, McCowin P, Davis D, et al. Abnormal magnetic resonance scans of the cervical spine in asymptomatic subjects. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1990;72:1178-1184.

62 Schellhas K, Smith M, Gundry C, et al. Cervical discogenic pain: prospective correlation of magnetic resonance imaging and discography in asymptomatic subjects and pain sufferers. Spine. 1996;21(3):300-311.

63 Teresi L, Lufkin R, Reicher M, et al. Asymptomatic degenerative disk disease and spondylosis of the cervical spine: MR imaging. Radiology. 1987;164:83-88.

64 Ferrante M, Wilson S, Iacobo C, et al. Clinical classification as a predictor of therapeutic outcome after cervical epidural steroid injection. Spine. 1993;18(6):730-736.

65 Bogduk N, April C. On the nature of neck pain, discography and cervical zygapophysial joint blocks. Pain. 1993;54:213-217.

66 Lord S, Barnsley L, Wallis B, et al. Percutaneous radio-frequency neurotomy for chronic cervical zygapophyseal-joint pain. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(23):1721-1726.

67 Manchikanti L, Boswell M, Singh V, et al. Prevalence of facet joint pain in chronic spinal pain of cervical, thoracic, and lumbar regions. BMC Musculoskeletal Disord. 2004;5(1):15.

68 McDonald G, Lord S, Bogduk N. Long-term follow-up of patients treated with cervical radiofrequency neurotomy for chronic neck pain. Neurosurgery. 1999;45(6):1499-1500.

69 Smith G, Pell J. Parachute use to prevent death and major trauma related to gravitational challenge: systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Br Med J. 2003;327:1459-1461.

70 Friedenberg Z, Miller W. Degenerative disc disease of the cervical spine. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1963;45:1171-1178.

71 Hitselberger W, Witten R. Abnormal myelograms in asymptomatic patients. J Neurosurg. 1968;28:204-206.

72 Poletti C. The neglected roots: C4, C3, C2. Atlanta, GA: Cervical Spine Research Society, 1998.

73 Toshimasa T. Cranial symptoms after cervical injury: aetiology and treatment of the Barre-Lieou syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg [Br]. 1989;71:283-287.