Fungal Infections, Infestations, and Parasitic Infections in Neonates and Infants

Dean S. Morrell, Shelley D. Cathcart, K. Robin Carder

Fungal infections

Infections caused by fungi and yeasts are common in neonates and infants. Among the most frequent are Candida infections such as thrush and diaper dermatitis. More extensive manifestations, such as congenital and systemic candidiasis, are much less common. Improvements in preterm infant survival due to advances in neonatal intensive care and an increase in bone marrow and organ transplantation have resulted in more frequent systemic fungal infections. Aspergillus is second only to Candida as a cause of opportunistic fungal infections in immunocompromised pediatric hosts. Zygomycosis and trichosporonosis are seen almost exclusively in premature infants. Malassezia species colonize the newborn skin and plays a role in a variety of clinical presentations such as neonatal cephalic pustulosis, tinea versicolor, or fungemia. Dermatophyte infections (mainly tinea capitis and tinea corporis) are the predominant cutaneous fungal infections during infancy in otherwise healthy infants and children.

Candidiasis

Epidemiology and pathogenesis

Candida is a common fungal pathogen. In newborns, infection may be acquired vertically from the mother or horizontally by nosocomial transmission in the nursery.1 The increasing use of antifungal prophylaxis with azoles has changed the epidemiology of candidemia in immunocompromised pediatric patients. C. albicans is responsible for approximately 45% of neonatal fungal infections, while non-albicans candidal species are increasing in incidence.2 Other Candida species associated with neonatal disease include C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis, C. lusitaniae, and C. glabrata. Normally, these yeasts are saprophytes, inhabiting the skin or gastrointestinal tract without invasion unless host defenses are altered. Candida spp. may also colonize endotracheal tubes and catheters without causing systemic illness, but associated clinical illness is common in very low-birthweight (VLBW) infants.3 In extremely low-birthweight (ELBW) infants (<1000 g), invasive candidiasis is more common. In one prospective study, 7% of 4379 infants had Candida isolated from blood or cerebrospinal fluid.4

Virulence mechanisms associated with Candida infections include fungal proteinase, increased adherence of yeast to epithelial cells due to similarity to mammalian cell ligands, and resistance to neutrophil ingestion of hyphal forms.5 Secretory IgA, functional T lymphocytes, and phagocytic cells are important in defense against Candida infections. Hence, there is increased susceptibility to these infections in patients with secretory IgA deficiency, primary T-cell deficiency such as DiGeorge syndrome, severe combined immunodeficiency, chronic granulomatous disease, myeloperoxidase deficiency, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. Recurrent or persistent yeast infections can be presenting symptoms of immunodeficiency. Host resistance to fungal infections also depends on activated macrophages, which in turn rely on T-lymphocyte release of interferon (IFN)-γ. Incomplete activation of macrophages by IFN in neonates6 contributes to increased susceptibility to invasive fungal disease.

Predisposing factors for Candida infections include excessive humidity, maceration, diabetes, and broad-spectrum antibiotics. Risk factors for systemic candidiasis in neonates include low birthweight, prematurity, broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy, indwelling catheters, prolonged endotracheal intubation, tracheostomy, prior fungal colonization, gastrointestinal pathology or abdominal surgery, enteral feeding, immunosuppression, defective neutrophil function or neutropenia, and steroid therapy.7–13 Similarly, pediatric patients with hematologic malignancies and neutropenia, short bowel syndrome with central vascular catheters or recent surgery or trauma (namely gastrointestinal/abdominal) are at increased risk of invasive candidiasis.2

Various techniques in addition to culture are used to evaluate the epidemiology of fungal pathogens. They include polymerase chain reaction (PCR), restriction fragment endonuclease digestion of chromosomal DNA, electrophoretic karyotyping, and Southern blot hybridization analysis using DNA probes, β-glucan assay (β-d-glucan is a major component of the fungal cell wall) and gas chromatography mass spectrometry for d-arabinitol (a major metabolite of most Candida species).1,14

Clinical presentations of candidal infections are discussed in this chapter, followed by diagnostic and treatment recommendations.

Congenital candidiasis

Congenital candidiasis (CC) refers to Candida infection acquired in utero and presenting with symptoms in the first days of life.15 Classic congenital candidiasis presents as a diffuse cutaneous infection, presumed to arise from an ascending intrauterine chorioamnionitis. The typical patient is an otherwise healthy term neonate who, within the first 12 h of life, develops a monomorphous papulovesicular eruption that is intensely erythematous (Figs. 14.1, 14.2, 14.3![]() ) progressing to pustules, crusting and desquamation. Any area of the body surface, including the face, palms, and soles, can be involved, and widespread involvement is often evident (Fig. 14.4). Candida paronychia and onychomycosis have been reported.14–17 Congenital candidiasis is surprisingly uncommon given the 33% rate of vaginal colonization with Candida in pregnant women.7 The presence of a foreign body in the maternal uterus or cervix is a risk factor for CC.15 In the majority of term infants, systemic dissemination of CC is rare. The prognosis of a term infant with CC is excellent, with rapid clearance of the eruption using topical treatment. Occasionally, CC can present as pneumonia and sepsis without cutaneous manifestations.18 CC with systemic involvement is more commonly seen in premature, low-birthweight infants (<1500 g).15,19–21 Skin findings in these infants may be variable, with a burn-like dermatitis (similar to staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome) in addition to the usual red scaly or vesiculopustular eruption (Fig. 14.5).15 A widespread rash in a premature or ill-appearing infant, respiratory distress in the immediate postnatal period, leukocytosis, or hyperglycemia should alert the physician to the possibility of systemic candidiasis despite negative blood cultures.15,21,22

) progressing to pustules, crusting and desquamation. Any area of the body surface, including the face, palms, and soles, can be involved, and widespread involvement is often evident (Fig. 14.4). Candida paronychia and onychomycosis have been reported.14–17 Congenital candidiasis is surprisingly uncommon given the 33% rate of vaginal colonization with Candida in pregnant women.7 The presence of a foreign body in the maternal uterus or cervix is a risk factor for CC.15 In the majority of term infants, systemic dissemination of CC is rare. The prognosis of a term infant with CC is excellent, with rapid clearance of the eruption using topical treatment. Occasionally, CC can present as pneumonia and sepsis without cutaneous manifestations.18 CC with systemic involvement is more commonly seen in premature, low-birthweight infants (<1500 g).15,19–21 Skin findings in these infants may be variable, with a burn-like dermatitis (similar to staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome) in addition to the usual red scaly or vesiculopustular eruption (Fig. 14.5).15 A widespread rash in a premature or ill-appearing infant, respiratory distress in the immediate postnatal period, leukocytosis, or hyperglycemia should alert the physician to the possibility of systemic candidiasis despite negative blood cultures.15,21,22

Systemic candidiasis

Systemic candidiasis (SC), defined as Candida infection in an otherwise sterile body fluid such as blood, urine, or cerebrospinal fluid, affects 2–7% of VLBW newborns.4,8,23 Skin manifestations occur in up to 60% of these infants.22 These infections can be acquired in utero (CC) or postnatally. In a multicenter prospective study, median gestational age and birthweight of neonatal invasive candidiasis was 30 weeks and 740 g, respectively.2 Only half of these patients had a central venous catheter at the time of diagnosis. Baley and Silverman23 described skin manifestations of VLBW infants with SC to include an extensive burn-like dermatitis followed by desquamation, progressive diaper dermatitis involving papules and pustules, and isolated diaper rash with or without thrush (Fig. 14.6).23 Cutaneous abscesses at the site of intravascular catheters may also be seen.7 Systemic signs include apnea, bradycardia, abdominal distension, guaiac-positive stools, hyperglycemia, temperature instability, leukemoid reaction, and hypotension.7,8,24 During childhood, invasive candidiasis occurs in immunocompromised individuals, especially those having had a central vascular catheter placed within 7 days of diagnosis.2 After hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, the median time to invasive candidiasis diagnosis is 74.5 days.2 Systemic candidiasis in immunocompromised children presents as randomly distributed deep, firm and erythematous papules and nodules.

Invasive fungal dermatitis

Invasive fungal dermatitis (IFD) is a clinicopathologic entity of erosive crusting lesions in VLBW infants. It is described by Rowen and colleagues25 as a primary skin condition that leads to secondary dissemination and systemic disease. It is primarily due to Candida albicans or other Candida species. Aspergillus, Trichosporon asahii, and Curvularia are also etiologic agents of invasive fungal dermatitis. Skin biopsy demonstrates fungal invasion beyond the stratum corneum, well into the epidermis, and at times extending into the dermis. Onset several days after birth, the presence of erosions and crusts, and typical histologic findings help to differentiate IFD from congenital candidiasis. Risk factors include extreme prematurity (<25 weeks’ gestational age), vaginal birth, steroid administration, and hyperglycemia.25

Localized candidiasis

Oral candidiasis (thrush).

Acute oral candidiasis appears on the oropharyngeal mucosa as white adherent curd-like plaques resembling milk or formula (Fig. 14.6). Plaques can be scraped off only with difficulty, leaving a bright erythematous base (pseudomembranous and erythematous forms, respectively). Extensive infection can lead to feeding difficulties, particularly if the esophagus is involved.7 Perlèche is a candidal infection involving the lateral angles of the mouth.

Candida diaper dermatitis.

Candida infection of the diaper area may occur alone or in conjunction with thrush. Bright, erythematous plaques, papules, and pustules affect the moist intertriginous areas of the perineum, with a predilection for inguinal creases. White scale and satellite pustules are common along the periphery, often prominent at the border of involved and uninvolved skin (Figs. 14.7, 14.8![]() ). Perianal involvement is common. Pustules may be very superficial and rupture easily leaving collarettes of scale. Candidal dermatitis may be seen in 4–6% of term newborns, with the incidence peaking at 3–4 months of age.7 Similar bright erythema may be seen in inverse psoriasis. Further differential diagnoses including infectious and noninfectious entities are outlined in Chapter 17.

). Perianal involvement is common. Pustules may be very superficial and rupture easily leaving collarettes of scale. Candidal dermatitis may be seen in 4–6% of term newborns, with the incidence peaking at 3–4 months of age.7 Similar bright erythema may be seen in inverse psoriasis. Further differential diagnoses including infectious and noninfectious entities are outlined in Chapter 17.

Candida infections of the nail plate and related structures.

Candidal infection of the nail plate and related structures may occur alone or in conjunction with systemic and congenital candidiasis. Candidal paronychia is common in finger-sucking children and presents with erythematous, edematous and tender nail folds with loss of cuticle. If present for months (chronic paronychia), resulting nail plate dystrophy can be seen distinguishing it from acute bacterial paronychia.

For onychomycosis secondary to Candida, finger sucking is a potential predisposing event (Figs. 14.9, 14.10, 14.11). The resultant onychodystrophy may lead to proximal-, distal-, and lateral-subungual, superficial white, or total dystrophic onychomycosis. The latter presents with a crumbling nail and an abnormally thickened nail bed. It is frequently seen in patients with chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis and other immunodeficiency states.26 Tinea unguium, hereditary onychodystrophy, ectodermal dysplasia, epidermolysis bullosa, psoriasis, and acrodermatitis may present with similar nail findings.

Diagnosis

Skin scrapings from pustules or peripheral scale should be examined using KOH solution, Giemsa, Gram, or calcofluor stains. Pseudohyphae and spores may be visualized with direct staining. Satellite pustules are most likely to yield positive results. Cultures from multiple sites, including skin, blood, cerebrospinal fluid, and urine, should be collected if systemic disease is suspected in premature infants or immunocompromised children. Culture yield is inconsistent,9 and negative cultures do not rule out systemic disease in the symptomatic infant.7 Buffy coat smear microscopy, a rapid bedside test with 100% specificity, can confirm candidemia within 1–2 h. Sensitivity is 62%, compared with 44% for peripheral blood smear examination.27 In some centers, buffy coat culture may yield results faster than whole blood cultures.27 A skin biopsy specimen may reveal a subcorneal pustule with neutrophils, and periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) staining will highlight the organisms. Invasive fungal dermatitis demonstrates invasion and inflammation of the epidermis, and possibly invasion of the dermis. In both neonates and children, Candida albicans is the etiologic organism in approximately 50% of candidal infections. As a group, the non-albicans species comprise the remaining causes.

Treatment

Localized forms of candidiasis can be treated topically in most term infants and healthy children. For thrush, nystatin solution (100 000 units/mL) is applied to the oral mucosa four times per day for at least 1 week. Resistant thrush may respond to once-daily oral fluconazole (2–3 mg/kg per day)28 or itraconazole (2 mg/kg per day),29 particularly in immunocompromised children. Oral amphotericin B has been studied for treatment of recurrent thrush.30 Imidazole creams are useful for diaper dermatitis and nail infection. Nystatin, allylamines (including naftifine and terbinafine), or aqueous solutions of 1% gentian violet or 2% eosin are alternatives for localized disease. Inflamed or erosive monilial diaper dermatitis may require a combination of the above with a 1% hydrocortisone cream or ointment and barrier paste containing zinc oxide. Oral nystatin or fluconazole may also be a useful adjunct for the treatment of diaper dermatitis, especially for recurrent disease, concurrent oral candidiasis or persistent cutaneous candidiasis in the setting of prolonged oral antibiotics thereby reducing the load of gastrointestinal Candida. Congenital candidiasis in asymptomatic term infants can be treated with topical agents alone. However, for ill and VLBW preterm infants, systemic treatment is recommended.15

In pediatric patients with invasive candidiasis, successful treatment outcomes are related to the candidal species causing the infection.2 C. parapsilosis and C. albicans have significantly better treatment outcomes than the more virulent C. glabrata infections. The drug of choice for systemic antifungal therapy evolves with candidal species, concurrent medical conditions and balance of potential medication side-effects. Early empiric systemic therapy reduces mortality in pediatric patients with candidemia. In ELBW infants, empiric treatment improves survival without associated neurodevelopmental impairment.31 Once the candidal species is indentified, adjustment of the antifungal agent may be necessary. In neutropenic patients, therapy should be continued for at least 14 days after last positive blood culture.32

Amphotericin B, a polyene macrolide antibiotic, has been a major therapeutic agent in systemic candidasis in immunocompromised patients. It is typically utilized in immunocompromised neutropenic patients with prior failed fluconazole prophylaxis or those at high risk of C. glabrata or C. krusei infections. Less commonly seen in neonates, the potential for nephrotoxicity warrants monitoring of renal function.33 Hepatotoxicity and bone marrow suppression are also potential side-effects.34 Lipid-associated amphotericin B formulations have less direct renal tubular toxicity and allow delivery of greater dosages, limits of infusion volume, and less toxicity.35 In addition to use in children, successful treatment of systemic fungal disease with these products has been reported in neonates.36 Both the liposomal and colloidal dispersion forms of amphotericin B were shown to be safe and effective in ELBW infants with candidemia and renal dysfunction.33,37 Furthermore, high-dose (5–7 mg/kg per day) liposomal amphotericin B may add a therapeutic advantage with more rapid eradication of infection when used as first-line therapy.38

Systemic fluconazole is commonly used in pediatric invasive candidal infections and has even been used successfully for treatment of systemic candidiasis in neonates.39–41 The recommended daily dose is 6 mg/kg per day for patients over 4 weeks of age, with less-frequent dosing for infants with compromised renal function and for those less than 4 weeks old. It is particularly useful in those with C. albicans infection and in whom amphotericin B is ineffective or contraindicated.33,39 When given in the first trimester of pregnancy, fluconazole has been reported to be teratogenic, leading to multiple malformations.42 Resistance to fluconazole can be seen especially in non-albicans Candida species (C. krusei, C. tropicalis, C. glabrata, C. parapsilosis), and also some C. albicans.32 Susceptibility testing can be performed to document the utility of these agents.32,43

Oral itraconazole administered at 5 mg/kg per day has been safe and well tolerated in infants and children;44,45 however, there are limited reports documenting its use in newborns with candidiasis.46 Oral ketoconazole (3–6.5 mg/kg per day) has been largely supplanted by the newer triazoles for candidiasis due to its risk of fulminant hepatitis.47

The echinocandins such as caspofungin and micafungin are a relatively new class of pediatric-approved antifungal agents, which irreversibly inhibit 1,3-β-d-glucan synthesis.48 These medications are fungicidal against Candida spp., including fluconazole-resistant strains, making them especially important for cases of non-albicans candidal infection. In general, the echinocandins have similar efficacy as amphotericin, with fewer adverse side-effects. In one study of caspofungin use in neonates with invasive candidiasis unresponsive to amphotericin B, all cultures cleared after 3–7 days of therapy without adverse events.48

Especially in C. parapsilosis infections, adjunctive therapy for systemic Candida infection includes changing or removing indwelling catheters when feasible.33 Possibly due to the inability to sterilize the subcutaneous tract of existing lines, exchange of peripherally inserted catheters is associated with a 25-fold increased risk of bloodstream infections.49 Placement of new vascular access at a different site is recommended.

Because ELBW infants and immunocompromised children are susceptible to and have a higher mortality risk from systemic Candida infections,50 prevention of infection by means of fluconazole prophylaxis should receive strong consideration. Potential concerns include unknown short- or long-term risks of fluconazole; uncertainty regarding the group of patients that would benefit most and the optimum dose and duration of therapy; and the potential for increased fluconazole resistance.51,52 Fluconazole has been shown to reduce rectal colonization with Candida.53 Bertini and colleagues54 gave fluconazole 6 mg/kg every 72 h for week 1, then daily for weeks 2–4 in neonates <1500 g with central venous access, and reduced the rate of candidemia from 7.6% to zero. Healy and coworkers55 initiated fluconazole prophylaxis in all ELBW infants of <5 days of age and reduced invasive candidiasis-related mortality from 12% to zero. As for dosing, twice-weekly fluconazole (3 mg/kg per dose) in ELBW infants with a central venous catheter or endotracheal tube was as effective as daily prophylaxis in decreasing Candida colonization and bloodstream infections.52 Meta-analysis of prophylactic fluconazole in this population found both agents to be safe and highly effective in preventing invasive candidiasis.56 Although these studies appear promising, larger multicenter studies looking closely at the morbidity and mortality rates from all causes, the emergence of resistant Candida strains, and unexpected consequences are still required.52

Malassezia infections

Malassezia (previously referred to as ‘Pityrosporum’ species) are saprophytic yeasts found on 90% of adults as normal skin flora. Skin colonization of newborns usually occurs in the first 1–3 months of life.3,57–59 By means of genetic analysis, the species formerly called Malassezia furfur has now been reclassified as M. furfur plus at least six other species.60 Although M. furfur is the most commonly associated species, M. pachydermatis, M. sympodialis, and M. globosa have also been associated with infections.59,61,62 Three clinical forms of Malassezia infection may present in children: tinea versicolor, cephalic pustulosis, and catheter-associated sepsis without cutaneous lesions.

Skin colonization with Malassezia species

Malassezia furfur is the main species responsible for human skin colonization and infection. Other Malassezia species, including M. sympodialis, M. globosa, and M. pachydermatis have also been implicated in human disease.59,61,62 Malassezia colonizes the skin of adults who are usually asymptomatic. Skin colonization begins in infancy, and the prevalence of colonization increases with age.58 The most common site of colonization in both infants (>78%) and neonates is the ear.58 Ashbee and collegues58 showed that 97.6% of infants (>28 days of age) and 31.8% of neonates were colonized; the mean age of colonization was 14 days.58 Risk factors for colonization include gestational age of <28 weeks and length of hospital stay >10 days.58 Fungal growth from skin and catheter cultures is not always associated with clinical sepsis.3

Tinea versicolor

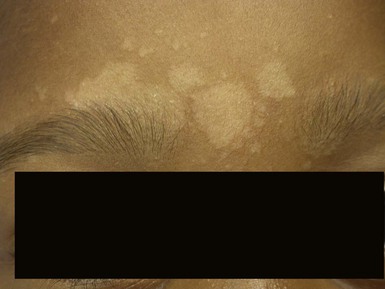

Due to the variation of sebum production during life, tinea versicolor (pityriasis versicolor) is less common in infants than in older children, adolescents, and young adults. However, young infants, particularly those less than 6 months of age, can have more sebum production under the influence of the fetal adrenal glands (so-called ‘mini-puberty of infancy’) and thus are more likely to develop tinea versicolor than older infants or pre-pubertal children. Facial involvement is very typical in affected infants and young children, although lesions may also be seen on the neck and upper trunk.63,64 Warm humid weather and immunosuppression induce greater growth of this yeast. A positive family history is variably present. Most commonly caused by M. globosa and M. furfur, tinea versicolor presents with multiple, 0.3–1 cm oval macules or plaques with fine scaling (Figs. 14.12![]() , 14.13). Relative to normal skin, lesions may be hypopigmented, skin-colored, or hyperpigmented. Wood’s light examination highlights the pigmentary changes and may produce a golden fluorescence. Differential diagnoses include pityriasis alba and postinflammatory hypopigmentation and hyperpigmentation.

, 14.13). Relative to normal skin, lesions may be hypopigmented, skin-colored, or hyperpigmented. Wood’s light examination highlights the pigmentary changes and may produce a golden fluorescence. Differential diagnoses include pityriasis alba and postinflammatory hypopigmentation and hyperpigmentation.

Neonatal cephalic pustulosis

Neonatal cephalic pustulosis (see Chapter 7) is a condition that was previously considered to be neonatal acne.60,65 During the second or third week of life, multiple, tiny, monomorphous papulopustules on an erythematous base begin on the face, scalp, and neck (Fig. 14.14). Contrary to classic acne, comedones are not a feature, and follicular accentuation is absent.65 Both M. globosa and M. sympodialis have been reported in association with neonatal cephalic pustulosis.59 Higher rates of colonization were associated with increased severity of pustulosis.59 Diagnosis is suggested by onset at 1 month of age, cephalic distribution, microscopic findings of yeast forms suggestive of Malassezia, exclusion of other pustular eruptions, and response to topical ketoconazole.65 The differential diagnosis of this pustular eruption is discussed more extensively in Chapters 7 and 10.

Malassezia sepsis

Malassezia fungemia is seen primarily in premature infants receiving intralipids through intravenous catheters. Skin colonization rates are much higher in premature infants than in full-term newborns, and the pathogenesis of disease probably involves organisms on the skin gaining venous access through indwelling catheters.61,66 Although in one study of VLBW infants (<1250 g), skin colonization with M. furfur was not predictive of catheter infection or systemic illness, the skin colonization rate was 63%, and positive M. furfur blood cultures were common (9.6%) in infants with central venous catheters.3 Clinical presentation ranges from asymptomatic colonization of the indwelling catheter to sepsis and death.3,66 Fever, apnea, bradycardia, and thrombocytopenia in the presence of negative routine bacterial cultures suggest fungal disease. Clusters of cases of infantile bronchopneumonia in neonatal units have also been attributed to M. furfur.66,67

Diagnosis and treatment of Malassezia infections

Malassezia can be identified by KOH preparation or Giemsa stain examination of the fine scales or pus; this will reveal clusters of spherical yeast and associated filaments. Malassezia is differentiated from Candida and other yeasts by a broader budding base. Malassezia furfur is a lipophilic yeast that requires fatty acid supplementation for growth. Modified Dixon agar or an olive oil overlay on routine fungal media is used for isolation of these fungi from blood specimens.

Cutaneous infections can be treated with an imidazole cream.47,65 A high level of suspicion for Malassezia sepsis is appropriate in premature infants with clinical signs of sepsis and negative bacterial and viral cultures, especially if intravenous lipid emulsions are being infused through venous catheters. Removal of the catheter and cessation of intravenous lipids, without systemic antifungal therapy, may be sufficient therapy for catheter-associated sepsis. Systemic antifungals may be considered if the infant does not show rapid clinical improvement.66

Trichosporonosis

Trichosporon asahii (formerly T. beigelii), a yeast found in soil and water, causes superficial mycoses in healthy persons (white piedra, onychomycosis, otomycosis).68 Invasive disease is possible in immunocompromised hosts and has emerged as a cause of systemic fungal disease especially in very premature infants. Both T. asahii and T. mucoides have been associated with invasive infection in premature neonates and immunocompromised children.68–70 Cutaneous manifestations of trichosporonosis are uncommon, but may include necrotic skin lesions or persistent generalized skin breakdown with serous or purulent drainage and white plaques; 68 neither erythema nor pustules are present. Unlike adults with trichosporonosis, neonates often have a normal absolute neutrophil count.68 Both colonization of central venous lines without evidence of disease and sepsis associated with fungal dissemination are reported in VLBW infants.68 Treatment is with a systemic antifungal agent. Trichosporon can exhibit tolerance to amphotericin B,71,72 and lack of fungicidal activity has been associated with treatment failure and death.71 Successful treatment of disseminated trichosporonosis with liposomal amphotericin B,68 amphotericin plus flucytosine,68 fluconazole,69 and voriconazole70,73 has been reported.

Aspergillosis

Aspergillus species are ubiquitous saprophytic fungi found in decaying vegetation and are infrequently pathogenic in healthy children.74 The conidia can spread through the air, and there are reports of acquisition in immunosuppressed patients following hospital construction work.75 A. fumigatus is the most common pathogen associated with human infection, followed by A. flavus and A. niger.74–76 The pathogenesis of disease with systemic Aspergillus infection involves invasion of blood vessels with subsequent thrombosis and tissue necrosis. Macrophage and neutrophil function is an important immunologic defense mechanism against Aspergillus infection.74–77 Risk factors for invasive aspergillosis include extreme prematurity, cystic fibrosis, neutropenia or neutrophil incompetence, immunosuppression from severe disease such as malnutrition or bacterial sepsis, and steroid-induced immunosuppression.74–77

Aspergillosis in children presents with a spectrum of diseases, including allergic bronchopulmonary hypersensitization, primary cutaneous aspergillosis, single-system involvement such as pulmonary or gastrointestinal aspergillosis, and disseminated aspergillosis. Mortality rates increase with more invasive disease. There can be overlap in clinical symptoms, and cutaneous lesions can be either primary or secondary to disseminated disease.

Primary cutaneous aspergillosis

Primary cutaneous aspergillosis (PCA) with infection limited to the skin is being reported more frequently in premature infants.74,75,77 It is often associated with breaks in normal skin integrity, such as occur with intravenous catheter insertion, or skin erosion or maceration secondary to the use of adhesive tape, monitor leads, or prolonged armboard use.74,76 Lesions are often confused with skin trauma or contact dermatitis, and diagnosis can be delayed unless a high level of suspicion is maintained. PCA may begin as a localized zone of erythema, evolving into a dark-red plaque with pustules, and finally a black eschar with a rim of erythema.74 Clustered, erythematous papules or pustules, or a necrotic plaque or nodule with an eschar, are characteristic (Fig. 14.15). The differential diagnosis includes ecthyma gangrenosum, zygomycosis, noninfectious vasculitis, and pyoderma gangrenosum.74 Histologic evaluation and culture of a biopsy specimen from the affected area can be diagnostic. Microscopically, vesicular surface erosion of a granuloma with infiltrating dichotomously branched (at 45° angles) septate hyphae is apparent. Growth of Aspergillus is supportive of a diagnosis, but lack of a positive culture does not rule out disease, especially if hyphal elements are seen on histologic examination.75

Systemic aspergillosis

Isolated pulmonary, gastrointestinal, and central nervous system aspergillosis may not be associated with skin findings; however, disseminated aspergillosis can have cutaneous manifestations, and cutaneous aspergillosis may disseminate. A morbilliform eruption that may become pustular is described with systemic aspergillosis.75 This presentation often represents embolic phenomena from fungal dissemination. Mortality from systemic aspergillosis in neonates is high compared with that of primary cutaneous aspergillosis (up to 100% vs 27%, respectively).75

Systemic antifungal therapy is recommended for all forms of systemic aspergillosis. Voriconazole or lipid formulations of amphotericin have been the standard antimicrobial agents prescribed. It is unclear whether complete surgical excision of cutaneous lesions is necessary for cure, but progression of the lesion during therapy may warrant surgical intervention.74

Cutaneous zygomycosis (mucormycosis, phycomycosis)

Zygomycosis is the term for infection caused by fungi in the Zygomycetes class. There are six fungal genera that cause disease in humans: Rhizopus, Cunninghamella, Mucor, Rhizomucor, Saksenea, and Absidia.78 These fungi are found in soil, decaying food, and other organic matter. Although infections may follow ingestion or inhalation of spores, direct inoculation into skin is the cause of primary cutaneous zygomycosis. It is seen predominantly in premature infants, as well as those who are immunocompromised from immunosuppressive drugs or underlying disease.78,79 Due to the selective pressure of more frequent use of newer (non-amphotericin) antifungal medications, some centers have reported an increase in invasive zygomycosis.80 Similar to aspergillosis, zygomycosis can involve the skin alone (primary cutaneous) or may involve other organ systems, including the gastrointestinal, pulmonary, and central nervous systems. Skin lesions may represent dissemination, or primary cutaneous infection may disseminate. Zygomycosis in immunocompetent hosts includes cutaneous zygomycosis and sinusitis. The cutaneous lesions may present as pustules with or without discrete erythematous cellulitis, and may develop a sharply defined, black, necrotic plaque producing a pathognomonic black pus (Fig. 14.16).79

In a review of 31 cases of neonatal zygomycosis, 22 were in premature infants, of which 12 had skin as the initial site of infection.78 Reports include an association with contaminated dressings and tongue depressors used as splints for intravenous and arterial cannulation sites.78,79,81 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that skin dressings be treated with cobalt irradiation as a preventive measure.79

Diagnosis is made by tissue biopsy and culture. Histologic examination shows large, nonseptate hyphae with right-angled branching.82 The fungus invades downward into tissue and blood vessels, frequently leading to thrombosis with dermal edema and minimal inflammatory infiltrate.82 Vascular invasion results in cutaneous ischemia and necrosis.78,82

Zygomycosis is treated with intravenous amphotericin B. As with aspergillosis, lipid formulations of amphotericin B can be used to deliver higher concentrations of drug, and other agents such as rifampin may be of use for antimicrobial synergy.78,83 In vitro data reveal resistance to azoles (except for Absidia), flucytosine, and naftifine.84 Although one successful case of medical treatment alone is reported,79 surgical debridement is often imperative in the treatment of cutaneous zygomycosis, and wide excision with clear margins of involved tissue is recommended.78,83 Overall mortality in invasive zygomycosis is 64% in neonates and 56% in children.85

Dermatophytosis

Dermatophytes are common fungal pathogens responsible for the cutaneous infection known as tinea. Clinical conditions are named according to the affected anatomic location: tinea capitis (scalp), tinea faciei (face), tinea corporis (body), tinea diaper dermatitis (diaper area), tinea unguium (nails), tinea cruris (groin) and tinea pedis (feet). Dermatophytosis may be acquired from infected caregivers, infected animals, or via fomites e.g. combs and brushes. Dermatophyte invasion of the stratum corneum is mediated by keratinase and other proteases.86 Cell-mediated immunity and evidence of a delayed-type hypersensitivity response are important in host resistance.86

In North America, dermatophyte infections in children are most often due to Trichophyton tonsurans and Microsporum canis.87–90 In Europe, M. canis is the most common, followed by T. mentagrophytes.90–93 The most common cause of tinea capitis in North America is Trichophyton tonsurans, which may also cause tinea faciei and corporis secondary to cutaneous spread. Fungal invasion in tinea capitis extends to the hair follicle, where infection may be either within the hair shaft (endothrix) or on the surface of the hair shaft (ectothrix). Neonatal tinea capitis has been reported with other fungal species, including T. rubrum, T. violaceum, and T. erinacei.90,94,95 Tinea diaper dermatitis is primarily due to T. rubrum and Epidermophyton floccosum.96 Tinea unguium in childhood has been caused by T. mentagrophytes and T. rubrum.97

Clinical findings

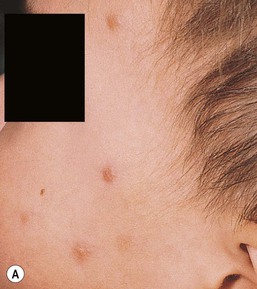

Dermatophyte infections in infants occur most commonly on the exposed scalp and face (Fig. 14.17)3,87–89,91–95 Tinea capitis often presents as erythematous, scaling areas with partial alopecia.90,93 Clinical manifestations vary from noninflammatory ‘black dot’ alopecia to a scaling, seborrheic dermatitis-like eruption without obvious hair loss (Fig. 14.18).90–92 Pustules may be present.87 Kerions can be seen in conjunction with tinea capitis.87 Kerions consist of pustules, nodules, and crusting, with underlying bogginess of scalp tissue. The inflammatory nature mimics a bacterial infection and often leads to unsuccessful therapy with antibacterial agents. Tinea capitis associated with kerion formation has been reported in a neonate.87 Posterior cervical lymphadenopathy is usually present. The kerion represents a delayed hypersensitivity reaction to the infection and may occur in 2% of patients with tinea capitis.98 Cultures from kerions can be negative in 40% of cases.98

Tinea infection on other parts of the body usually presents as annular plaques with superficial scaling and/or tiny pustules.89,94,95 These may be mistaken for dermatitis; facial tinea may mimic neonatal lupus. Cases of tinea faciei and tinea corporis have been reported in neonates.88,94,99 Cases of resistant diaper dermatitis in infants as a result of dermatophytes have been described.96 In tinea diaper dermatitis, the presence of annular or arcuate plaques with a scaling peripheral border is a clue to the diagnosis (Fig. 14.19).

Tinea pedis was once thought to be rare in young infants. While certainly not as common as in teens or adults, many cases have been reported. A major risk factor is the presence of tinea pedis or onychomycosis in one or more family members. The clinical presentations are similar to those in older patients including web-space scaling as well as scaling of the forefoot. Because of low level of suspicion, many affected children are misdiagnosed as having a dermatitis.100,101

Onychomycosis, fungal infection of the nail, can be caused by dermatophytes, nondermatophyte molds, and Candida. Tinea unguium, caused by dermatophytes, is uncommon in prepubertal children but is occasionally seen.97 Candida onychomycosis is a relatively common finding in neonates with congenital cutaneous candidiasis.14,17 Nails may have superficial white opaque patches, or yellowish discoloration with subungual hyperkeratosis. Hereditary onychodystrophy, acquired trachyonychia, psoriasis, lichen planus, and trauma may cause similar findings.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of dermatophytosis can be confirmed by several tests. A Wood’s light examination may have limited usefulness in the diagnosis of tinea capitis; positive fluorescence is seen in ectothrix hair infections, but is absent in the more common endothrix infections such as those caused by Trichophyton. All suspected tinea infections should be confirmed by culture, or lesional scale or hair microscopically examined under 10% potassium hydroxide (KOH) solution or alternative stains (see Chapter 6). Although KOH preparations may demonstrate spores and hyphae, false-negative examinations are common. Scrapings of scales, brush or cotton-tipped applicator swabbings of the affected skin, or collections of hair are cultured on fungal media. Dermatophytes are slow growing and may take up to 1 month to grow in culture, although common pathogens generally grow within 2 weeks. Skin biopsy, although rarely necessary for diagnosis, may reveal hyperkeratosis with parakeratosis and a mixed inflammatory perivascular dermal infiltrate. Staining with periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) or Grocott–Gomori methenamine silver nitrate reveals fungal elements in the stratum corneum and possibly the hair follicle.47

Treatment

Treatment of tinea capitis usually requires systemic antifungal therapy. Griseofulvin has been used for decades and successful safe treatment even in neonates has been reported.87,90,93 Griseofulvin suspension doses of 20–25 mg/kg per day for 8 weeks may be needed.87,90,93 Ultramicrosized griseofulvin is better-absorbed allowing for reduced dosages at 15–20 mg/kg per day. Fluconazole (6 mg/kg per day) may also be effective.102 Terbinafine is fungicidal and may require shorter treatment durations. Experience with terbinafine in neonates is limited, but has been studied in children as young as 2 years of age with good tolerance demonstrated. Terbinafine, dosed at 5–8 mg/kg daily for 6 weeks, has been shown to have efficacy against both Trichophyton and Microsporum species in pediatric cases of tinea capitis.103,104 Although topical therapy alone was successful in treatment of infants (mostly preterm infants with M. canis tinea capitis) during a nursery outbreak,93 it is not generally recommended for tinea capitis.88,93 A well-reported complication of tinea capitis is auto-eczematization (‘id’ reaction) which occurs in a minority of patients, typically those with either severe or long-standing disease. This reaction typically manifests as intensely pruritic monomorphic and symmetrically distributed papules on the hair line, ears, and upper torso and proximal extremities. Onset is usually just after the initiation of systemic treatment of tinea capitis, however it does not represent true allergy to the oral antifungal medication.

Tinea faciei, corporis, and pedis can be successfully treated with topical applications of azoles such as clotrimazole, econazole, and miconazole. Ciclopirox, as well as allylamines such as terbinafine or naftifine and amorolfine, may also be used.105,106 If persistent, systemic griseofulvin or fluconazole for a period of 4–8 weeks may be required.102,107 Majocchi’s granuloma is a follicular dermatophyte infection on non-scalp locations. These granulomatous dermatophyte infections typically occur when the initial superficial fungal infection is mis-treated with topical steroids allowing the dermatophyte to invade hair follicles. Systemic treatment is necessary to eradicate this deeper dermatophyte infection. It is important to identify the potential source of the fungal infection in family members. The prognosis for dermatophyte infections is excellent.

Ectoparasitic infestations

Mites, lice, bed bugs, flea larvae, protozoa, and helminth worms cause a variety of cutaneous lesions.47 Mites are classified in the order Acari, class of arthropods Arachnida. The prototype is scabies, which is the most common parasitic infection in humans. Flea larvae (myiasis) and other mites (demodicidosis) can also cause disease in children.

Scabies

Introduction

Scabies is a common ectoparasitic infestation caused by the mite Sarcoptes scabiei ssp. hominis. Initial infestation by scabies may be asymptomatic. A primary symptom of scabies is generalized pruritus, which intensifies at night. Infants, however, may not manifest symptoms despite extensive infection. Pruritus in a neonate unable to scratch may present as irritability, insomnia, and poor feeding. Congenital scabies is not seen, but infestation can develop in very young infants.108,109

Cutaneous findings

Skin findings include a generalized erythematous vesiculopapular eruption, with lesions commonly concentrated on the axillae, neck, palms, soles, and sometimes the head (in young infants, Fig. 14.20). In older children and adults, the head and neck are usually spared. A burrow is the pathognomonic sign of scabies. Burrows appear as a small thin line with a tiny black dot at one end, indicating the location of the female mite. They are found primarily on the hands, flexural aspect of the wrists (Fig. 14.21), and medial or lateral aspects of the feet; visualization may be difficult because of secondary eczematous changes.

In infants, vesicles and pustules are characteristically found on the palms and soles. Nodules representing a hypersensitivity reaction may also appear, primarily in intertriginous areas, during active infection, and persist for some time after scabies has been successfully treated. Recurrent vesicular lesions similar to scabetic nodules may be manifestations of ongoing hypersensitivity response to the initial infestation.

A form of infantile scabies (scabies incognito) clinically resembling crusted scabies is associated with prior topical corticosteroid therapy.109 In addition to the generalized eruption, crusted and hyperkeratotic lesions on the palms and soles are described.110 Unlike classic crusted scabies in adults, which is characterized by intense infestation by Sarcoptes mites, these infants lacked subungual hyperkeratosis and high mite counts.110 There has also been a report in immunosuppressed children of a unique form of scabies consisting of fine scaling and minimal to absent pruritus, mimicking seborrheic dermatitis.111

Etiology and pathogenesis

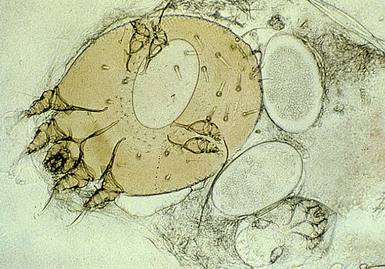

The scabies mite is an obligate human ectoparasite unable to survive more than a few days without a host.108 The microscopic adult female mite has eight legs and measures 400 µm. Throughout its life span of up to 30 days, the mite burrows into the stratum corneum, laying up to three eggs per day. Larvae hatch in 3–4 days, and mature into adult mites within 10–14 days.108 Although only a few mites are present, hundreds of skin lesions may develop owing to hypersensitivity.108

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is based on the clinical findings, as well as a history of contact with persons having a similar pruritic eruption. Definitive diagnosis is based on microscopic visualization of scrapings from a burrow or papule, demonstrating the mite, eggs, or scybala (feces) (Fig. 14.22) (see Chapter 6). Skin biopsy is rarely necessary. Histopathologic examination shows a mixed dermal inflammatory infiltrate with eosinophils and epidermal spongiosis. The mites, ova, and nymphs may also be seen.

Treatment

The treatment of choice for scabies is permethrin 5% cream. It is approved for use in infants as young as 2 months old, with one report of safety and efficacy in a 23-day-old infant.108 Permethrin is a neurotoxin that causes paralysis and death of ectoparasites; it has low potential for toxicity in humans, and there is no evidence of resistance to date.104 Efficacy is superior to that of lindane, crotamiton, benzyl benzoate, and sulfur.104 Permethrin applied to the entire body surface, including the scalp, and left on for 8–12 h is 89–92% effective.108 Reapplication 1 week later is advisable. Critical to success is the simultaneous treatment of all family members and close contacts, even if asymptomatic. In households in which not all members are treated, it is not uncommon for the return of lesions in initially improved patients. Whereas adults are treated from the neck down, children under 2 years of age should have the head treated as well. In addition, bedding and clothing of patients and all contacts should be washed the following day in hot water for at least 5 min, or dry cleaned. Antihistamines such as hydroxyzine (2 mg/kg per day in divided doses every 6–8 h) and a corticosteroid ointment such as triamcinolone 0.1% may help control the residual pruritus and eczematous dermatitis that can persist for several weeks following successful eradication of the parasite. Ivermectin, an avermectin with antiparasitic and anti-nematode properties, has been used orally in cases of refractory scabies,112 but it is not recommended for use in patients under 15 kg body weight.

Pediculosis capitis (head lice)

Introduction

Head lice infestation is common in the pediatric population, affecting 1–10% of school-aged children.113 The causative insect Pediculus humanus var. capitis is spread by close person-to-person contact and by fomites (combs, hats, pillows, etc.).114

Cutaneous findings

Although head lice are less commonly seen in infants than in school-aged children, infants are at risk of infestation through close physical contact and fomite sharing with older siblings. The most common presenting symptom is scalp pruritus.

Etiology

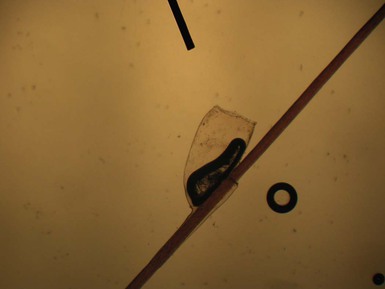

Adult lice are 1–2 mm long or approximately the size of a sesame seed (Fig. 14.23![]() ). They lay eggs on the hair shaft in firmly adherent casings called ‘nits’ usually within 2 mm of the scalp (Fig. 14.24).114

). They lay eggs on the hair shaft in firmly adherent casings called ‘nits’ usually within 2 mm of the scalp (Fig. 14.24).114

Diagnosis

Visualization of lice attached to the hair shaft is diagnostic and they are most commonly found behind the ears and at the nape of the neck.114

Treatment

Traditional lice treatments include permethrin 1% rinse (available as Rid® and Nix® in the USA without a prescription) and malathion 0.5% lotion (requires a prescription). Resistance to pyrethroids is unfortunately becoming widespread and treatment requires several repeat applications due to poor ovicidal activity of these compounds.115 Malathion has efficacy data in patients as young as 2 years of age and has been shown to be superior to permethrin in ovicidal activity.116 While high alcohol content of the vehicle requires caution around an open flame, there are no verified reports of bodily harm due to burns when using this product.116

Although it was a first-line treatment in the past, lindane (gamma-benzene-hexachloride) is now rarely used due to significant risk of neurotoxicity (seizure, headache, dizziness, and paresthesia) and other adverse events, especially in pediatric populations.117 Resistance to both permethrin and malathion has been reported118 and new therapies are available. Spinosad 0.9% topical solution is approved for use in children over four years of age.119 Spinosad is ovicidal, killing both lice and nits, and has been shown to be superior to permethrin 1% cream rinse.120 Ivermectin 0.5% lotion (Sklice®) is also recently approved and has safety data in children as young as 6 months of age.

Physical treatment modalities such as hot air directed at the scalp to desiccate the insect121 and suffocation therapy (application of olive oil, mayonnaise, etc. to the scalp) have also been shown to be effective treatments.122,123 In children over 2 years of age, oral ivermectin (at a dose of 400 µg/kg of body weight) has been shown to be effective for malathion-resistant head lice cases as well.124 Most treatments are repeated 7–10 days after the initial application to ensure eradication of any lice hatching from eggs that survived the first round of therapy. Use of a nit comb is also helpful to physically remove potentially resistant eggs from the hair shaft. Nit combs are helpful as an adjunct but are insufficient as solo therapy.125 All close contacts should be treated simultaneously as lice infestation can be asymptomatic.126 Lice can survive off the human host for up to 55 h and nits can survive up to 10 days. Therefore, measures to treat the environment are also recommended. All washable fomites (clothes, bedding, etc.) should be laundered in hot water and dried on high heat for at least 40 min.127 Non-launderable items should be placed in a bag for 3 weeks or dry-cleaned. Fumigation with pesticides is not recommended.

Enterobiasis (pinworms)

Enterobiasis is due to infestation with the nematode Enterobius vermicularis. Infestation is most common in school-aged children but is easily transmitted to household contacts and may be seen in younger infant siblings. Although most infestations are asymptomatic, it may present as nocturnal perianal pruritus. The pruritus is caused when the gravid female pinworm deposits her eggs in the mucosa of the perianal area at nighttime. Traditional diagnosis is by the application of clear cellophane tape to the perianal area upon waking followed by microscopic examination of the tape for the presence of eggs. Treatment with antihelminths such as mebendazole, albendazole or pyrantel should be prescribed for the patient and all close contacts. Treatment should be repeated in 1 week.

Cutaneous larva migrans

Cutaneous larva migrans, also called ‘creeping eruption,’ is due to larvae of the dog and cat hookworm (Ancylostoma caninum and Ancylostoma braziliensis) burrowing in human epidermis. Humans are accidental hosts and the hookworm is unable to complete its normal life cycle. Instead, the larvae are confined to the epidermis and migrate aimlessly for 1–2 months until they die. They cause significant pruritus and linear erythematous serpiginous plaques on the skin that lengthen up to 1–2 mm/day. The infestation responds to treatment with traditional oral antihelminthic medications (albendazole, mebendazole, ivermectin, etc).

Demodicidosis

Demodicidosis presents as perioral dermatitis, pustular folliculitis, and blepharitis.128 Pruritic erythematous papules, pustules, nodules, and scaling occur primarily on the face, most commonly on the dorsum of the nose.129 Demodex folliculorum and D. brevis are human ectoparasites that are normal inhabitants of the pilosebaceous ducts and glands. D. canis causes mange in animals. The role of the mite Demodex in human cutaneous disease is controversial.128 To date, the youngest reported case is that of a 10-month-old infant.127 Demodicidosis is found mainly in immunosuppressed children,128,130 although disease in healthy hosts has been described.129 A well-described scenario in children occurs in those with acute lymphocytic leukemia on maintenance chemotherapy. Mites may be seen when skin scrapings are examined using KOH or when a skin biopsy is performed. A dramatic response may be seen within 2–3 weeks after the application of 5% permethrin cream.128 Topical metronidazole and oral erythromycin help decrease the numbers of mites and may offer additional benefit.128,129

Myiasis

Myiasis is a parasitic infestation of dipterous larvae in mammals, found worldwide but primarily in the tropics and subtropics.131 Cutaneous myiasis may occur in pre-existing wounds or present as a furuncle. Passage of maggots, discharge, a foul odor, and pain may be reported.132,133 Myiasis is classified clinically according to the body site affected, as cutaneous, nasopharyngeal, ocular, aural, intestinal, or genital. There have been reports of myiasis in neonates and infants chiefly in rural settings,132 although cases have also been reported in urban centers and neonatal intensive care units.133 The diagnosis is made clinically and confirmed by identification of larvae, which can be preserved in 80% ethanol. Treatment involves extraction of the larvae by irrigation, manipulation, or ideally with surgery followed by debridement, cleansing, and possible primary suture closure.131

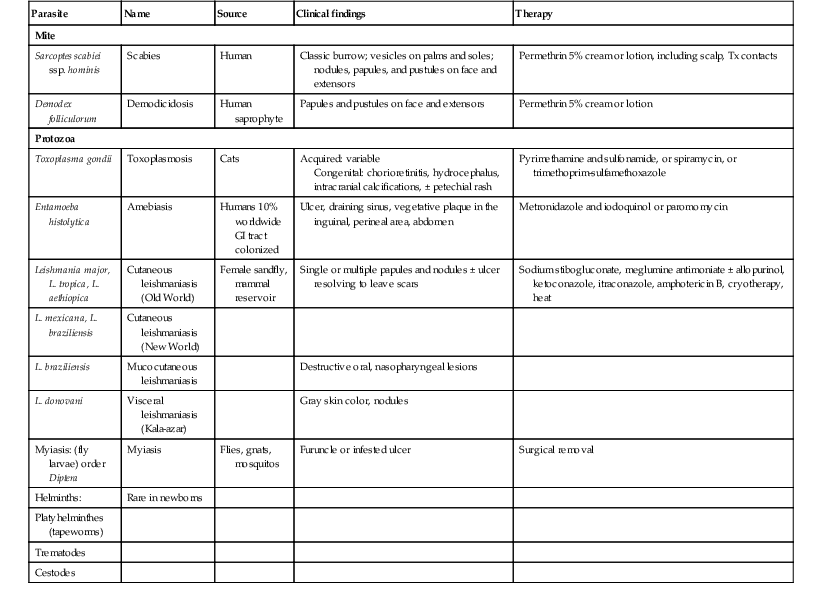

Parasitic infections

Parasitic infections with cutaneous manifestations are more commonly seen in developing countries. Table 14.1 presents a summary of cutaneous diseases due to parasites. Toxoplasma are autonomous, single-cell organisms that are acquired in utero more frequently than postnatally. Cutaneous manifestations of helminth worms are discussed minimally here, but are treated in depth by Stein.47

TABLE 14.1

Parasitic cutaneous infections in neonates

| Parasite | Name | Source | Clinical findings | Therapy |

| Mite | ||||

| Sarcoptes scabiei ssp. hominis | Scabies | Human | Classic burrow; vesicles on palms and soles; nodules, papules, and pustules on face and extensors | Permethrin 5% cream or lotion, including scalp, Tx contacts |

| Demodex folliculorum | Demodicidosis | Human saprophyte | Papules and pustules on face and extensors | Permethrin 5% cream or lotion |

| Protozoa | ||||

| Toxoplasma gondii | Toxoplasmosis | Cats | Acquired: variable Congenital: chorioretinitis, hydrocephalus, intracranial calcifications, ± petechial rash |

Pyrimethamine and sulfonamide, or spiramycin, or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole |

| Entamoeba histolytica | Amebiasis | Humans 10% worldwide GI tract colonized |

Ulcer, draining sinus, vegetative plaque in the inguinal, perineal area, abdomen | Metronidazole and iodoquinol or paromomycin |

| Leishmania major, L. tropica, L. aethiopica | Cutaneous leishmaniasis (Old World) | Female sandfly, mammal reservoir | Single or multiple papules and nodules ± ulcer resolving to leave scars | Sodium stibogluconate, meglumine antimoniate ± allopurinol, ketoconazole, itraconazole, amphotericin B, cryotherapy, heat |

| L. mexicana, L. braziliensis | Cutaneous leishmaniasis (New World) | |||

| L. braziliensis | Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis | Destructive oral, nasopharyngeal lesions | ||

| L. donovani | Visceral leishmaniasis (Kala-azar) | Gray skin color, nodules | ||

| Myiasis: (fly larvae) order Diptera | Myiasis | Flies, gnats, mosquitos | Furuncle or infested ulcer | Surgical removal |

| Helminths: | Rare in newborns | |||

| Platyhelminthes (tapeworms) | ||||

| Trematodes | ||||

| Cestodes | ||||

Toxoplasmosis

Toxoplasmosis is caused by the intracellular protozoon Toxoplasma gondii.134–136 Infection commonly occurs through consumption of undercooked meats containing Toxoplasma cysts or oocysts excreted by cats.136,137 Toxoplasmosis may be acquired congenitally or postnatally. Severity of fetal disease varies inversely with gestational age at the time of infection. Thus early infection more likely leads to fetal death or severe neurologic and ophthalmologic disease.137 Most newborns infected in the second or third trimester have mild or subclinical manifestations. In at least 40% of cases, the infection is discovered late, manifesting as chorioretinitis, visual impairment, and neurologic sequelae.135,137 Risk of fetal infection is estimated to be <1–19.6/10 000 live births worldwide, varying with geographic location.138

Congenital toxoplasmosis has no specific cutaneous manifestations,134–136 but petechial and nonpetechial rashes were seen in, respectively, 17% and 14% of affected infants.139 Deep blue-red papules and macules and nonspecific exanthems, both with involvement of the palms and soles, and a calcifying dermatitis have been described in affected neonates.136 Neurologic sequelae such as seizures, hydrocephalus, microcephaly, and neuropsychomotor developmental delay are the main clinical manifestations.137 Intracranial calcifications and increased CSF protein may be seen. Eye abnormalities include chorioretinitis (95%), microphthalmia, cataracts, and retinal detachment. The most common clinical presentation of eye involvement is strabismus, seen in 49% of affected infants.137 Neonatal disease may include systemic findings of hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, hyperbilirubinemia, and thrombocytopenia. The prognosis of congenital toxoplasmosis has improved with therapy; however, many cases are not recognized in the newborn period.134

Postnatally acquired toxoplasmosis is asymptomatic in the majority of patients, but disease in immunocompromised hosts can be serious. Cutaneous manifestations are variable and include macular, papular, pustular, or vesiculobullous eruptions.136 The eruption may be hemorrhagic and may resemble roseola or erythema multiforme.47 Lymphadenopathy and hepatosplenomegaly may accompany these eruptions.

The diagnosis of toxoplasmosis is based on isolation of the organism, characteristic histopathology of lymphadenitis, detection of Toxoplasma antigens in tissues and body fluids, and detection of Toxoplasma nucleic acid by PCR. The most commonly used diagnostic tool is serology. Both the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and immunosorbent agglutination assay (ISAGA) are useful tests.135 The Sabin–Feldman dye test entails the uptake of methylene blue by Toxoplasma trophozoites lyzed in the presence of specific antibody and complement. It is very specific but only available through reference laboratories.135 PCR testing of amniotic fluid replaced cordocentesis for the prenatal diagnosis of fetal infection.140

Symptomatic acquired or congenital toxoplasmosis should be treated with pyrimethamine, sulfadiazine, and folinic acid.135 Treatment should be continued for at least 1 year.

Leishmaniasis

Leishmaniasis is a parasitic infection due to Leishmania species (family Trypanosomatidae). There are 400 000 new cases each year in Asia, Africa, the Mediterranean, and the Americas. The flagellated, extracellular promastigote is transmitted by female phlebotomine sandflies to animal reservoirs, including rodents and dogs.141 There it becomes an obligate intracellular amastigote. Reports of infants with leishmaniasis living in nonendemic areas emphasize the need to consider this diagnosis when unusual skin lesions are present.141–144 Leishmaniasis is classified into the following categories: visceral (L. donovani, L. infantum), mucocutaneous (L. braziliensis), Old World cutaneous (L. major, L. tropica, L. aethiopica), and New World cutaneous (L. mexicana, L. braziliensis) (Table 14.1).145

Visceral leishmaniasis due to L. donovani presents with fever, wasting of the face and extremities, hepatosplenomegaly, ascites, pancytopenia, and earth-gray skin pigmentation on the temples, perioral area, hands, and feet.141 There may be a papular lesion seen early at the site of the sandfly bite. Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis due to L. braziliensis invades the midface, nose, and upper respiratory tract. A sporotrichoid lymphatic form has been described with L. braziliensis and L. major.

In countries where leishmaniasis is prevalent, infants and children are frequently affected by cutaneous leishmaniasis. The initial lesion is an erythematous papule derived from an insect bite that evolves to form a relatively painless crusted ulcer.141 It is typically on an exposed site (primarily on the face and hands) (Fig. 14.25), paired or clustered, with a volcanic or iceberg appearance, and oriented to the skin creases. Satellite papules or nodules may be present with surrounding erythema.144 Secondary bacterial infection is common. The lesions generally heal spontaneously in 3–12 months, although they may also evolve into chronic, treatment-resistant forms that are localized, lupoid, or disseminated.

Diagnosis is based on smears or skin biopsy specimens that permit visualization of the amastigote, culture, or animal inoculation that produces characteristic lesions.141 The leishmanin skin test evaluates the degree of induration after an intradermal injection of antigen. Positive findings are seen 1–3 months after the initial lesion in cutaneous leishmaniasis. Serologic studies are most valuable in visceral leishmaniasis.141

Although visceral leishmaniasis is usually fatal if untreated, spontaneous resolution is the rule in cutaneous forms of the disease. Indications for treatment include lesions that are early, multiple, mucosal, or in cosmetically sensitive sites. Disseminated disease in an immunodeficient host also warrants treatment. If treatment is needed, there is no single ideal drug. Primary treatment is with pentavalent antimonials such as intramuscular or intravenous sodium stibogluconate (10–20 mg/kg per day) or meglumine antimonate (not available in the USA).146 Ketoconazole and amphotericin B may also be effective, and temperature-sensitive Leishmania may respond to cryotherapy or heat.121

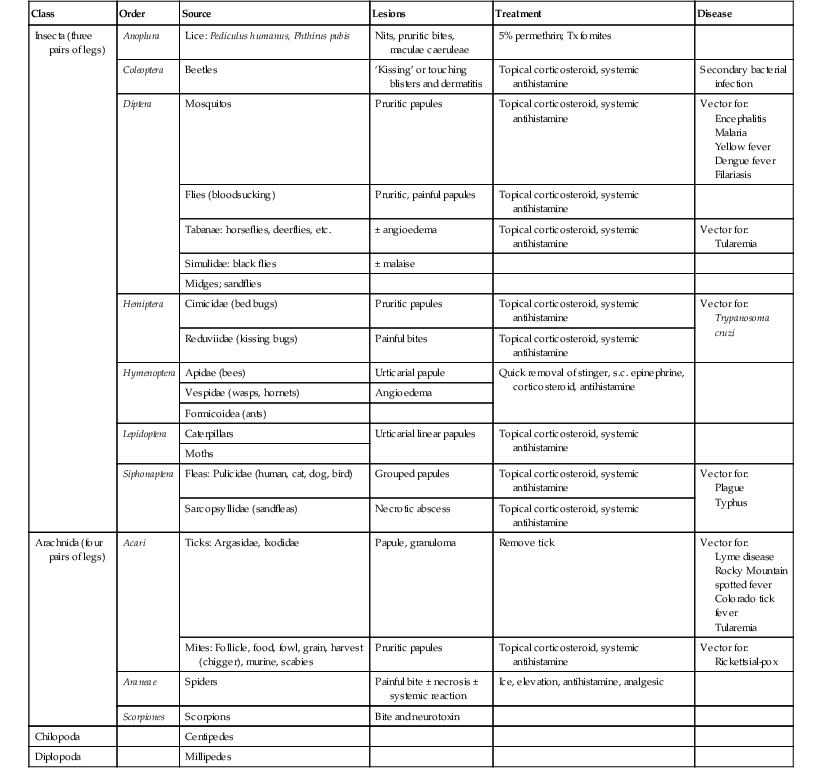

Arthropod bites and stings

Arthropod bites and stings may cause a variety of skin lesions, as well as be vectors for disease. Erythematous, urticarial papules and pustules with a central punctum can be seen, most commonly on exposed surfaces (Fig. 14.26). Vesicular lesions may be a manifestation of a hypersensitivity response and not indicative of bacterial infection, particularly in infants and young children. These pink, raised lesions are typically arranged in groups. Persistence of lesions for weeks to months (papular urticaria) is rarely seen in the first year of life.147 Specific lesions and subsequent diseases are outlined in Table 14.2.

TABLE 14.2

Arthropod bites and stings

| Class | Order | Source | Lesions | Treatment | Disease |

| Insecta (three pairs of legs) | Anoplura | Lice: Pediculus humanus, Phthirus pubis | Nits, pruritic bites, maculae caeruleae | 5% permethrin; Tx fomites | |

| Coleoptera | Beetles | ‘Kissing’ or touching blisters and dermatitis | Topical corticosteroid, systemic antihistamine | Secondary bacterial infection | |

| Diptera | Mosquitos | Pruritic papules | Topical corticosteroid, systemic antihistamine | Vector for: Encephalitis Malaria Yellow fever Dengue fever Filariasis |

|

| Flies (bloodsucking) | Pruritic, painful papules | Topical corticosteroid, systemic antihistamine | |||

| Tabanae: horseflies, deerflies, etc. | ± angioedema | Topical corticosteroid, systemic antihistamine | Vector for: Tularemia |

||

| Simulidae: black flies | ± malaise | ||||

| Midges; sandflies | |||||

| Hemiptera | Cimicidae (bed bugs) | Pruritic papules | Topical corticosteroid, systemic antihistamine | Vector for: Trypanosoma cruzi |

|

| Reduviidae (kissing bugs) | Painful bites | Topical corticosteroid, systemic antihistamine | |||

| Hymenoptera | Apidae (bees) | Urticarial papule | Quick removal of stinger, s.c. epinephrine, corticosteroid, antihistamine | ||

| Vespidae (wasps, hornets) | Angioedema | ||||

| Formicoidea (ants) | |||||

| Lepidoptera | Caterpillars | Urticarial linear papules | Topical corticosteroid, systemic antihistamine | ||

| Moths | |||||

| Siphonaptera | Fleas: Pulicidae (human, cat, dog, bird) | Grouped papules | Topical corticosteroid, systemic antihistamine | Vector for: Plague Typhus |

|

| Sarcopsyllidae (sandfleas) | Necrotic abscess | Topical corticosteroid, systemic antihistamine | |||

| Arachnida (four pairs of legs) | Acari | Ticks: Argasidae, Ixodidae | Papule, granuloma | Remove tick | Vector for: Lyme disease Rocky Mountain spotted fever Colorado tick fever Tularemia |

| Mites: Follicle, food, fowl, grain, harvest (chigger), murine, scabies | Pruritic papules | Topical corticosteroid, systemic antihistamine | Vector for: Rickettsial-pox |

||

| Araneae | Spiders | Painful bite ± necrosis ± systemic reaction | Ice, elevation, antihistamine, analgesic | ||

| Scorpiones | Scorpions | Bite and neurotoxin | |||

| Chilopoda | Centipedes | ||||

| Diplopoda | Millipedes |

s.c., subcutaneous.

Skin lesions are caused by four of the nine classes of arthropod: Insecta, Chilopoda, Diplopoda, and Arachnida.148 Although the terms bite and sting are often used interchangeably, in the strict sense, a ‘bite’ involves venom injected via structures of the mouth, such as fangs or mandibles, whereas a ‘sting’ connotes the injection of venom via a tapered posterior structure called the sting.149 Secondary bacterial infection must be considered in infants with bites and stings. The presence of fever and wound drainage is suggestive of infection and may warrant antibiotic therapy.

Papular urticaria

Brief introduction

Papular urticaria is a hypersensitivity reaction to a wide variety of insect bites (bed bugs, flea, mosquitoes, flies, mites, chiggers, etc.) seen most frequently in children age 2–10 years.

Cutaneous findings

Papular urticaria is characterized by chronic or recurring eruptions of multiple pruritic papules, vesicles or wheals that occur on exposed areas of the body such as the arms and legs (Fig. 14.27). In the case of bed bugs and other walking insects, bites are characterized by linear arrangement of erythematous papules and are often found in groups of three (‘breakfast, lunch and dinner’ sign). It can be extremely resistant to therapy and individual lesions can persist for months. New insect bites can cause old lesions to become inflamed again.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is based on the cutaneous findings and a history of exposure to insects. In the case of bed bugs, a search of mattress seams or rough cracks and crevices can reveal areas where the insects remain hidden during the daytime. Asking about pets and possible flea exposure is also a helpful part of the history. For mosquito exposure, the caregivers will often report a history of the rash flaring during the times of the year that mosquitoes are most active.

Etiology

The cause of papular urticaria is widely varied and often depends upon the region in which it occurs.150,151 In the southeast, it is most commonly caused by mosquitoes and tends to flare in the summer months. In the western USA, however, fleas and bed bugs are more common causes and seasonal variation is less notable. Other, rarer causes of papular urticaria include Cheyletiella and rat and bird mites.

Treatment

Caregivers are often resistant to this diagnosis and therapy requires establishing their trust and agreement with the treatment plan. Accompanied by behavior modifications to decrease scratching, oral antihistamines and application of high-potency topical steroid under occlusion leads to improvement in most cases. All efforts at treatment should be accompanied by the use of insect repellants to prevent exposure to new bites. Definitive management of bed bug infestation will require extermination by a professional who is familiar with the treatment of these insects113 and all pets should be appropriately treated for fleas.

Access the full reference list at ExpertConsult.com ![]()

Figures 2, 3, 8, 10, 12 and 23 are available online at ExpertConsult.com ![]()