42 Fungal infections

Fungi are ubiquitous microorganisms that differ from bacteria in their cellular structure, and this makes them naturally resistant to antibacterial agents (Table 42.1). Fungi are broadly divided into yeasts and moulds. Yeasts are typically round or oval shaped microscopically, grow flat round colonies on culture plates and reproduce by forming buds from their cells. Moulds (e.g. Aspergillus, Mucor) appear as a collection or mass (mycelium) of individual tubular structures called hyphae that grow by branching and longitudinal extension. They appear as a fuzzy growth on appropriate conducive medium (e.g. Penicillium colonies on stale bread or Sabourauds agar). The most commonly seen yeast, Candida, occasionally produces pseudohyphae.

Table 42.1 Important characteristics of a fungal cell

| Fungi | Bacteria |

|---|---|

| Eukaryotes | Prokaryotes, eubacteria |

| Cell and cytoplasm | Cell and cytoplasm |

| Nucleus with multiple chromosomes enclosed in a nuclear membrane | No nucleus or nuclear membrane, has single chromosome |

| Contains endoplasmic reticulum, golgi apparatus, mitochondria and ribosomes | Other structures absent except ribosomes |

| Cytoplasmic membrane | Cytoplasmic membrane |

| Contains phospholipids and sterols | Contains phospholipids and no sterols |

| Cell wall | Cell wall |

| Contains chitins, mannans,+/- cellulose | Contains peptidoglycan, lipids and proteins |

There are hundreds of species of fungi found in the environment, but only the important human fungal pathogens and their treatment will be discussed in this chapter. The fungi of medical importance can be divided into four groups (Table 42.2).

Table 42.2 Classification of fungi of medical importance

| Group | Examples | Infections caused |

|---|---|---|

| Yeast | Candida spp. | Oral and vaginal thrush |

| Deep seated: candidaemia, empyema | ||

| Cryptococcus neoformans | Meningitis | |

| Saccharomyces cervesiae | Rare systemic infection in immunocompromised host | |

| Malassezia furfur | ||

| Yeast-like | Geotrichium candidium | |

| Trichosporon beigelii | ||

| Dimorphic fungi | Blastomyces dermatitidis | For first three: deep systemic organ involvement, more commonly in the immunocompromised host |

| Coccidioides immitis | Deep subcutaneous infection following trauma | |

| Histoplasma capsulatum | ||

| Paracoccidioides brasiliensis | ||

| Sporothrix schenckii | ||

| Moulds | ||

| 1. Hyaline | ||

| a. Zygomyces | Rhizopus | Infections in neutropenic patients and those with diabetic ketoacidosis |

| Mucor | ||

| Absidia | ||

| b. Hyalohyphomycosis | Aspergillus fumigatus and other Aspergillus spp. | Systemic infection: invasive pulmonary or central nervous system involvement |

| Fusarium | Fusarium keratitis | |

| Scedosporium apiospermum | Deep infection in immunocompromised host, for example, transplant patients | |

| 2. Dermatophytes | Trichophyton spp. | For all three: various skin (ringworm) hair and nail infections |

| Microsporum spp. | ||

| Epidermophyton | ||

| 3. Dematiaceous | Alternaria spp. | Deep tissue infection with granulomas |

| Cladophialora spp. | Chromomycosis, mycetomas | |

Some fungi like Histoplasma capsulatum, Coccidioides immitis, Blastomyces dermatitidis are known as dimorphic fungi (Table 42.2) because they are found in the infected host in yeast form at 35–37 °C temperature but grow as moulds, in vitro, at room temperatures (22 °C incubation).

Fungal infection

More often, fungi are a cause of superficial infections of the skin and mucous membranes.

Antifungal agents

Topical and systemic antifungal agents are available to treat mucocutaneous candidiasis, various forms of tinea (ringworm) and other dermatophytosis, onychomycosis and deep-seated systemic infections (e.g. candidaemia, mucor mycoses, fungal endocarditis, osteomyelitis). Some infective conditions and their treatment are dealt with in the sections that follow. The side effects of a range of antifungal agents are set out in Table 42.3.

| Drug | Side effects |

|---|---|

| Griseofulvin | Mild: headache, gastro-intestinal side effects. Hypersensitivity reactions such as skin rashes, including photosensitivity |

| Moderate: exacerbation of acute intermittent porphyria; rarely, precipitation of systemic lupus erythematosus. Contraindicated in both acute porphyria, systemic lupus erythematosus, pregnancy and severe liver disease | |

| Terbinafine | Usually mild: nausea, abdominal pain; allergic skin reactions; loss and disturbance of sense of taste. Not recommended in patients with liver disease |

| Amphotericin | Immediate reactions (during infusion) include headache, pyrexia, rigors, nausea, vomiting, hypotension; occasionally, there can be severe thrombophlebitis after the infusion |

| Nephrotoxicity and hypokalaemia | |

| Anaemia due to reduced erythropoiesis | |

| Peripheral neuropathy (rare) | |

| Cardiac failure (exacerbated by hypokalaemia due to nephrotoxicity) | |

| Immunomodulation (the drug can both enhance and inhibit some immunological functions) | |

| Flucytosine | Mild: gastro-intestinal side effects (nausea, vomiting). Occasional skin rashes Moderate: myelosuppression (dose related), hepatotoxicity |

| Fluconazole | Mild: nausea, vomiting and occasional skin rashes; occasionally, elevated liver enzymes (reversible) |

| Moderate or severe: rarely, hepatotoxicity and severe cutaneous reactions, especially in AIDS patients | |

| Itraconazole | Mild: nausea and abdominal pain; occasional skin rashes |

| Moderate or severe: rarely, hepatotoxicity | |

| Voriconazole | Similar to fluconazole and itraconazole |

| Mild: reversible visual disturbances occur in about 30% patients | |

| Caspofungin | Mild: gastro-intestinal side effects; occasional skin rashes |

Superficial infection

Candida infections

Treatment

Systemic treatment

Three triazole agents: fluconazole, itraconazole and voriconazole are available for systemic treatment of oral and vulvo vaginal candidiasis (VVC). A good source of advice on treatment is that from the Infectious Diseases Society of America (Pappas et al., 2009):

Guidance on the treatment of topical and systemic therapy (Pappas et al., 2009) are also available for treatment of mild, moderate and severe oropharyngeal and oesophageal candidiasis and suppressive therapy for patients with HIV infection.

Fungal infections in the compromised host

Common mycoses

Epidemiology and predisposing factors

There are a large number of conditions which may predispose the individual to systemic or deep-seated fungal infection. These are summarised in Table 42.4. A breach in the body’s mechanical barriers may predispose to fungal infection. For example, fungal infection of the urinary tract occurs most commonly in catheterised patients who have received broad-spectrum antibiotics, while total parenteral nutrition (TPN) is strongly associated with fungaemia, sometimes with unusual fungi such as Malassezia furfur. This is due to the use of TPN infusions containing lipids, which are a growth requirement of this organism. Most cases of systemic fungal infection, however, are associated with a defect in the patient’s immune system, and the nature of the organisms encountered is often related to the nature of the immunosuppression. Neutropenia, for example, is usually associated with Candida species, Aspergillus and mucormycosis, while defects of cell-mediated immunity, for example HIV infection, are strongly associated with infection by Cryptococcus neoformans. Prolonged diabetic ketoacidosis is a risk factor for developing rhinocerebral zygomycosis where mortality can be as high as 100% if there is significant underlying disease.

Table 42.4 Conditions predisposing to systemic or deep-seated fungal infection

| Infection | Predisposing conditions |

|---|---|

| Systemic candidiasis | Neutropenia from any cause (disease or treatment) |

| Use of broad-spectrum antibiotics which eliminate the normal body flora | |

| Indwelling intravenous cannulae, especially when used for total parenteral nutrition | |

| Haematological malignancy and HSCT | |

| Solid organ transplantation | |

| AIDS (particularly associated with severe mucocutaneous infection) | |

| Intravenous drug abuse | |

| Cardiac surgery and heart valve replacement, leading to Candida endocarditis | |

| Gastro-intestinal tract surgery | |

| Oesophagectomy leak leading to pleural space infection (empyema) | |

| Aspergillosis | Neutropenia from any cause, especially if severe and prolonged |

| Acute leukaemia | |

| Solid organ transplantation (mainly lungs) | |

| Chronic granulomatous disease of childhood (defect in neutrophil function) | |

| Pre-existing lung disease (usually leads to aspergillomas; fungus balls form in the lung rather than invasive or disseminated infection) | |

| Cryptococcosis | AIDS |

| Systemic therapy with corticosteroids | |

| Renal transplantation | |

| Hodgkin’s disease and other lymphomas | |

| Sarcoidosis | |

| Collagen vascular diseases | |

| Zygomycosis | Diabetic hyperglycaemic ketoacidosis (leading to rhinocerebral infection) |

| Severe, prolonged neutropenia | |

| Burns (leading to cutaneous infection) |

HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

Many different fungi have been described as causing systemic fungal infection, but the most common organisms encountered and the conditions they cause are listed in Table 42.5. Of these, Candida and Aspergillus are by far the most common in the UK.

Table 42.5 Common causes of systemic and deep-seated fungal infection in the UK

| Condition/organism | Common clinical presentations |

|---|---|

| Candidiasis (Candida albicans, C. glabrata, C. krusei, C. tropicalis, other Candida species) | Fungaemia |

| Colonisation of intravenous cannulae | |

| Pneumonia | |

| Meningitis | |

| Bone and joint infections | |

| Endocarditis | |

| Endophthalmitis | |

| Peritonitis in chronic ambulatory peritoneal dialysis | |

| Aspergillosis (Aspergillus fumigatus, A. flavus, other Aspergillus species) | Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis |

| Disseminated aspergillosis | |

| Aspergilloma | |

| Endocarditis | |

| Cryptococcosis (Cryptococcus neoformans) | Meningitis |

| Pneumonia | |

| Cutaneous infection | |

| Zygomycosis (various species of the genera Rhizopus, Mucor, Absidia) | Rhinocerebral infection |

| Pulmonary mucormycosis | |

| Surgical wound and burns infection | |

| Malassezia furfur | Cutaneous infection (especially in burns patients) |

| Fungaemia associated with total parenteral nutrition |

Clinical presentation

Symptoms can be non-specific like low-grade fever, night sweats, weight loss, cough, chest pain and septic shock in extreme cases (Table 42.6).

Table 42.6 Clinical presentation of systemic fungal infection

| Condition | Clinical presentation |

|---|---|

| Fungaemia (the presence of fungi in the bloodstream), usually due to Candida species | Fever, low blood pressure and sometimes other features of septic shock, especially in neutropenic patients |

| Relatively low-grade fungaemias such as those associated with colonised intravenous cannulae often present only with fever | |

| Disseminated infection to multiple organ systems is quite common with Candida species, leading to central nervous system disease, endocarditis, endophthalmitis, skin infections, renal disease, bone and joint infection | |

| Pneumonia, most frequently due to Aspergillus species | Fever, chest pain and cough which may be non-productive. May progress rapidly, especially with Aspergillus infection, to severe respiratory distress, necrosis of the lung and pulmonary haemorrhage |

| Formation of fungal balls in pre-existing lung cavities with or without invasion | |

| Meningitis and other central nervous system infection | Candida infection may present as a typical meningitis, although it is often more insidious. |

| Aspergillosis is associated with headache, confusion and focal neurological signs due to the presence of brain infarcts. Cryptococcosis most frequently presents as a chronic, insidious meningitis with headache and alteration in mental state | |

| Mucormycosis | Angioinvasive. The most common presentation of mucormycosis is rhinocerebral infection. |

| Initially an infection of the sinuses, it then spreads locally to the palate, orbit and eventually into the brain, leading to encephalitis | |

| Pulmonary disease can present as fungal balls radiologically with symptoms of haemoptysis |

Treatment

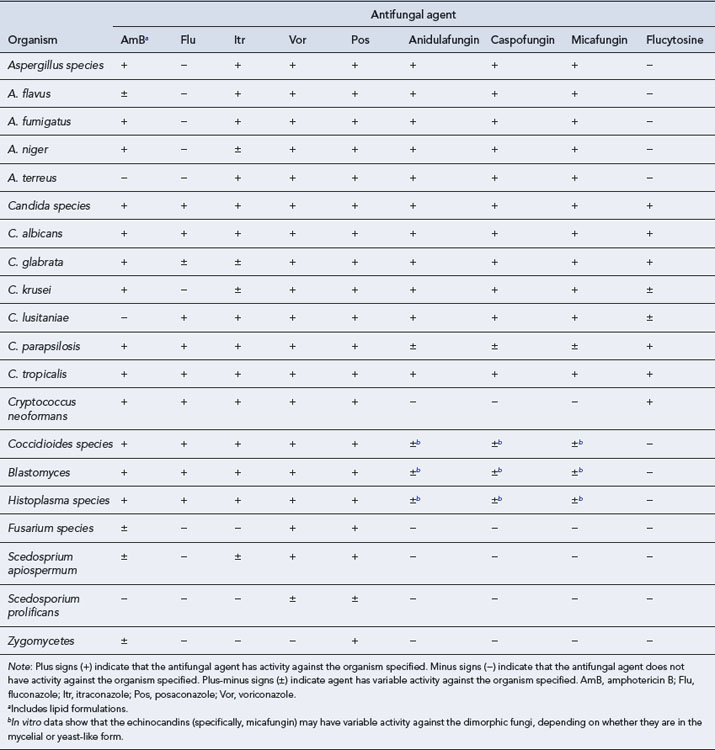

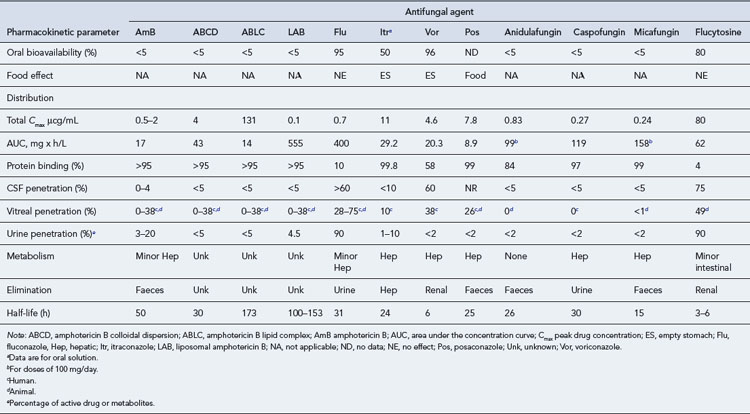

Compared to the vast array of antibacterial agents available to treat bacterial infections, there are very few systemic antifungal agents available and these comprise four major categories: the polyenes (conventional and lipid formulations of Amphotericin B), the triazoles (fluconazole, itraconazole, voriconazole and posaconazole), the echinocandins (caspofungin, anidulafungin and micafungin) and flucytosine. To provide optimal therapy to the patient, it is necessary to understand the profile, properties and toxicity of these agents. Table 42.7 details the antifungal spectrum of activity against common fungi.

Amphotericin B

Amphotericin B lipid formulations

Flucytosine

Side effects

Some of the side effects of flucytosine are given in Table 42.3. The most important toxic effect is a dose-related myelosuppression with neutropenia and thrombocytopenia. This is usually reversible and can be avoided by monitoring serum levels of flucytosine and adjusting the dose accordingly. Hepatotoxicity is also probably a result of high serum levels, and liver function tests should be performed regularly. The drug is teratogenic in some animals and is not recommended in pregnant women for relatively trivial infections such as a fungal urinary tract infection. In cases of a life-threatening fungal infection, which is very rare in pregnancy, the potential benefits of flucytosine must be weighed against the possible risks.

Triazoles

Three triazoles are licensed in the UK: fluconazole, itraconazole and voriconazole. They differ substantially from one another in their pharmacokinetic and antifungal activity (Table 42.8). Their main side effects are listed in Table 42.3.

Itraconazole

Clinical use

In deep-seated infection, itraconazole is used to treat infections due to the ‘pathogenic’ fungi, but there is less published evidence of its use in the treatment of systemic candidiasis and it cannot be recommended for this purpose (Maertens and Boogaerts, 2005). However, it may be useful in patients who are infected with strains resistant to fluconazole, some of which may remain sensitive to itraconazole, and in patients who are for some reason unable to tolerate fluconazole. It has also been used to treat cryptococcosis, despite its poor penetration of cerebrospinal fluid, and in that condition, it is an alternative to fluconazole for patients who cannot take the latter drug. However, one study comparing fluconazole and itraconazole as maintenance treatment for cryptococcosis was discontinued due to the high rate of relapse in the itraconazole arm.

Voriconazole

Clinical use

The main clinical indication for the use of voriconazole is aspergillosis. Studies have shown improved efficacy compared to conventional amphotericin B in systemic Aspergillus infection. The largest randomised control trial demonstrates that voriconazole is superior to amphotericin B deoxycholate as primary therapy of Aspergillosis (Walsh et al., 2008). One particular indication is cerebral aspergillosis. Although rare, this carries a high mortality rate (90% or higher), and one study has shown this to be reduced by voriconazole, presumably due to its better penetration into the central nervous system. In addition to aspergillosis, voriconazole is also licensed for the treatment of Fusarium infection and for the management of patients infected with strains of Candida resistant to fluconazole. It has been shown to be as efficacious as amphotericin B followed by fluconazole in the treatment of candidaemia in patients who were not neutropenic, but it is not licensed for this indication.

Caspofungin

Clinical use

Caspofungin is only available for administration via the intravenous route and does not penetrate into the cerebrospinal fluid. Due to its spectrum of activity, caspofungin is indicated only for candidiasis and aspergillosis. A comparative study showed caspofungin to be as efficacious as conventional amphotericin B in invasive candidiasis. It has been shown to be effective in patients with aspergillosis who failed to respond to, or who could not tolerate, other antifungal agents. Finally, caspofungin was also shown to be as effective as liposomal amphotericin B in the empirical treatment of fungal infection in neutropenic patients and had a lower incidence of unwanted effects (Walsh et al., 2004). In the UK, the drug is licensed for this indication.

Choice of treatment

Practice points regarding the drug toxicity in systemic antifungal agents are detailed in Table 42.9.

| Drug toxicity in systemic antifungal agents | |

| Infusion-related side effects | • Particularly with conventional amphotericin B |

| • Lipid-based preparations also show these, but to a lesser extent | |

| Nephrotoxicity | • Particularly with conventional amphotericin B |

| • Results in renal dysfunction | |

| • Cessation of treatment may be required | |

| • Drug-level monitoring is not helpful in prevention | |

| • Potassium loss and hypokalaemia are a serious complication | |

| • Renal toxicity may be potentiated by concomitant nephrotoxic agents | |

| Hepatotoxicity | • Associated with the azole antifungals |

| • Was particularly severe with ketoconazole | |

| • The newer triazoles may also cause serious liver damage | |

| Bone marrow suppression | • Associated with flucytosine |

| • Dose-related problem, so drug-level monitoring may help to prevent it | |

| • Tends to preclude the use of flucytosine in patients whose marrow is already damaged (e.g. in haematological malignancy or following bone marrow transplant) | |

| Drug interactions | • Associated particularly with the azoles |

| • Due to their mode of action in inhibiting the cytochrome P450 system | |

| • A wide range of drugs may be affected, some with serious interactions | |

| Difficulties in drug administration | |

| Drug precipitation | • Amphotericin B will precipitate out if given in electrolyte-containing infusions |

| • This may also happen in 5% dextrose due to acidity resulting from the manufacturing process | |

| Need for a test dose | • Required for all amphotericin B preparations |

| Long infusion times and/or large infusion volumes | • A particular problem with conventional amphotericin |

| • Long infusion times mean reduced access to intravenous cannulae for other purposes | |

| • Large infusion volumes may be undesirable in patients with renal or cardiac dysfunction | |

| Variable absorption when taken by mouth | • A known problem with itraconazole |

| • Absorption is reduced in the presence of raised gastric pH (e.g. following the use of antacids or drugs such as omeprazole) | |

| • Absorption is increased in the presence of food or if taken with a cola drink | |

| • Subtherapeutic levels may occur due to poor absorption | |

| • Therapeutic drug monitoring is recommended to avoid low levels | |

| Resistance to antifungal agents | |

| Amphotericin B | • Usually seen as a very broad-spectrum antifungal, but inherent resistance is seen in several clinically significant species: |

| Aspergillus terreus | |

| Candida lusitaniae | |

| Scedosporium apiospermum | |

| • Acquired resistance developing during treatment is very uncommon | |

| • Lipid preparations have identical in vitro antifungal activity to the conventional form | |

| Flucytosine | • Acquired resistance during treatment is very common in Candida species |

| • Monotherapy promotes the rapid development of resistance | |

| • Combination therapy with amphotericin will reduce the possibility of acquired resistance developing during treatment | |

| Fluconazole | • Some species of Candida are inherently resistant or less susceptible to fluconazole: |

| C. krusei | |

| C. glabrata | |

| • Long-term use of fluconazole may result in increased infections with these more resistant strains | |

| • Long-term use may also result in reduced susceptibility in strains of C. albicans | |

Dodds Ashley E.S., Lewis R., Lewis S.J., et al. Pharmacology of systemic antifungal agents. Clin. Infect. Dis.. 2006;43:S28-S39.

Maertens J., Boogaerts M. The place for itraconazole in treatment. J. Antimicrob. Chemother.. 2005;56:i33-i38.

Pappas P.G., Kauffman C.A., Andes D., et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of candidiasis: 2009 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis.. 2009;48:503-553.

Walsh T.J., Teppler H., Donowitz G.R., et al. Caspofungin versus liposomal amphotericin B for empirical antifungal therapy in patients with persistent fever and neutropenia. N. Engl. J. Med.. 2004;351:1391-1402.

Walsh T.J., Anaissie E.J., Denning D.W., et al. Treatment of aspergillosis: clinical practice guidelines of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis.. 2008;46:327-360.

Bennett J.E. Introduction to mycoses. In: Mandell G.L., Bennett J.E., Dolin R., editors. Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. seventh ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2010:3221-3240.

Hay R.J. Dermatophytosis and other superficial mycoses. In: Mandell G.L., Bennett J.E., Dolin R., editors. Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. seventh ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2010:3345-3355.

Pfaller M.A., Pappas P.G., Wingard J.R. Invasive fungal pathogens: current epidemiological trends. Clin. Infect. Dis.. 2006;43:S3-14.

Rex Rex, J.H., Stevens, D.A., Systemic antifungal agents. In: Mandell, G.L., Bennett, J.E., Dolin, R. (Eds.), Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases, seventh ed. Elsevier, Philadelphia, pp. 549–563.

Winn W., Allen S., Janda W., et al. Mycology. In Koneman’s Colour Atlas and Textbook of Diagnostic Microbiology, sixth ed, Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2006:1153-1232.