Fungal Diseases of the Lung

After reading this chapter, you will be able to:

• List the anatomic alterations of the lungs associated with fungal disease.

• Describe the causes of fungal disease.

• List the cardiopulmonary clinical manifestations associated with fungal disease.

• Describe the general management of fungal disease.

• Describe the clinical strategies and rationales of the SOAPs presented in the case study.

• Define key terms and complete self-assessment questions at the end of the chapter and on Evolve.

Anatomic Alterations of the Lungs

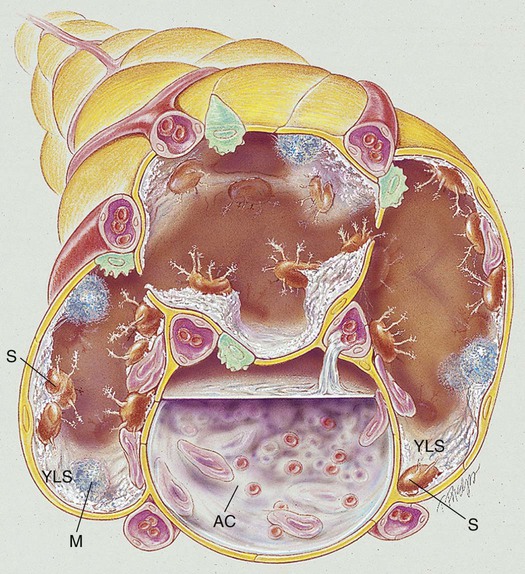

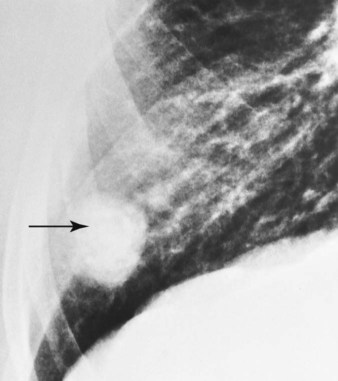

When fungal spores are inhaled, they may reach the lungs and germinate. When this happens, the spores produce a frothy, yeastlike substance that leads to an inflammatory response. Polymorphonuclear leukocytes and macrophages move into the infected area and engulf the fungal spores. The pulmonary capillaries dilate, the interstitium fills with fluid, and the alveolar epithelium swells with edema fluid. Regional lymph node involvement commonly occurs during this period. Because of the inflammatory reaction, the alveoli in the infected area eventually become consolidated (Figure 18-1). Airway secretions may also develop at this time.

General Management of Fungal Disease

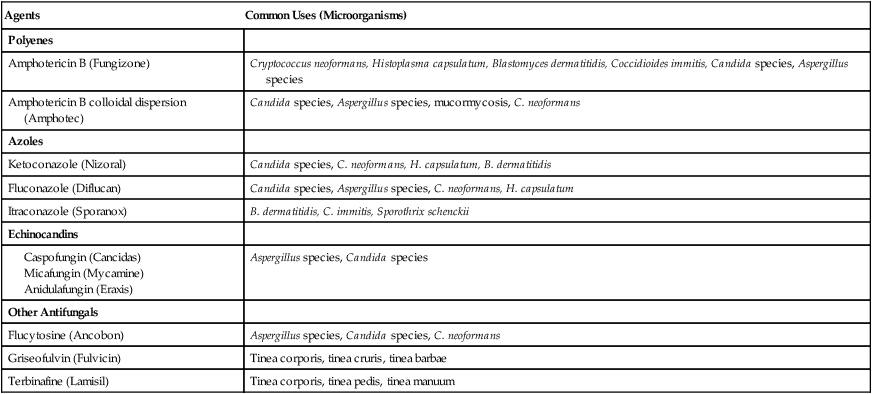

The antifungal agents are the first line of defense in treating fungal lung infections. In general, the drug of choice for most fungal infections is intravenously administered polyene amphotericin B (Fungizone). Although ketoconazole was used as a first-line agent against common fungal organisms, it has largely been replaced by the trizoles, fluconazole and itraconazole. The echinocandins, a relatively new class of antifungal agents, are now available (Table 18-1).

Table 18-1

| Agents | Common Uses (Microorganisms) |

| Polyenes | |

| Amphotericin B (Fungizone) | Cryptococcus neoformans, Histoplasma capsulatum, Blastomyces dermatitidis, Coccidioides immitis, Candida species, Aspergillus species |

| Amphotericin B colloidal dispersion (Amphotec) | Candida species, Aspergillus species, mucormycosis, C. neoformans |

| Azoles | |

| Ketoconazole (Nizoral) | Candida species, C. neoformans, H. capsulatum, B. dermatitidis |

| Fluconazole (Diflucan) | Candida species, Aspergillus species, C. neoformans, H. capsulatum |

| Itraconazole (Sporanox) | B. dermatitidis, C. immitis, Sporothrix schenckii |

| Echinocandins | |

Modified from Gardenhire DS: Rau’s respiratory care pharmacology, ed 7, St Louis, 2008, Elsevier.

Respiratory Care Treatment Protocols

Oxygen Therapy Protocol

Oxygen therapy is used to treat hypoxemia, decrease the work of breathing, and decrease myocardial work. Because of the hypoxemia associated with the fungal pulmonary condition, supplemental oxygen may be required. Because of the alveolar consolidation produced by a fungal disorder, capillary shunting may be present. Hypoxemia caused by capillary shunting is often refractory to oxygen therapy. In addition, when the patient demonstrates chronic ventilatory failure during the advanced stages of fungal disease, caution must be taken not to overoxygenate the patient (see Oxygen Therapy Protocol, Protocol 9-1).

Bronchopulmonary Hygiene Therapy Protocol

Because of the excessive mucous production and accumulation sometimes associated with fungal disease, a number of bronchial hygiene treatment modalities may be used to enhance the mobilization of bronchial secretions (see Bronchopulmonary Hygiene Therapy Protocol, Protocol 9-2).

Mechanical Ventilation Protocol

Mechanical ventilation may be necessary to provide and support alveolar gas exchange and eventually return the patient to spontaneous breathing. Because acute ventilatory failure is occasionally seen in patients with severe fungal disease, continuous mechanical ventilation may be required. Continuous mechanical ventilation is justified when the acute ventilatory failure is thought to be reversible (see Mechanical Ventilation Protocols, Protocol 9-5, Protocol 9-6, and Protocol 9-7).

CASE STUDY

Fungal Diseases of the Lungs

Admitting History

Respiratory Assessment and Plan

S “I feel short of breath, and my joints are swollen and painful.”

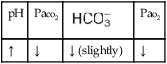

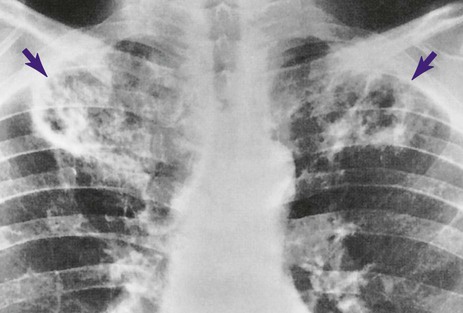

O Cyanosis; cough: frequent and strong, producing moderate amounts of thick, yellow sputum; vital signs: BP 160/90, HR 90, RR 18, T 37.8° C (100° F); palpation: red lesions on anterior chest and left cheek; auscultation: bilateral crackles and rhonchi in lung apices; CXR: bilateral fibrosis and calcification and spheric nodules; two to three 1- to 3-cm cavities in both upper lobes; ABGs (room air): pH 7.51, Paco2 29,  22, Pao2 64

22, Pao2 64

• Moderate respiratory distress (cyanosis, vital signs)

• Large amounts of thick, yellow secretions (sputum, rhonchi)

• Infection likely (yellow sputum)

• Pulmonary fibrosis, calcification, and cavities (CXR)

• Acute alveolar hyperventilation with mild hypoxemia (ABGs)

P Initiate Oxygen Therapy Protocol (2 L/min per nasal cannula) and Bronchopulmonary Hygiene Therapy Protocol (C&DB instruction, PD to both upper lobes q shift × 3 days). Order sputum culture (routine, AFB, and fungal). Encourage fluid intake. Monitor (oximeter, I&O).

Respiratory Assessment and Plan

S “I still can’t get a good breath of air.”

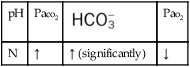

O Respiratory distress: cyanotic, short of breath; positive spherulin skin test; coccidioidomycosis organisms seen in sputum smear; frequent strong cough: moderate amount of thick, opaque sputum; vital signs: BP 165/95, HR 96, RR 24, T normal; bilateral crackles and rhonchi in the lung apices; Spo2 88%; ABGs: pH 7.54, Paco2 27,  21, Pao2 55

21, Pao2 55

• Coccidioidomycosis (positive spherulin skin test, sputum smear)

• Continued respiratory distress (cyanosis, vital signs)

• Excessive amounts of thick bronchial secretions (sputum, rhonchi)

• Acute alveolar hyperventilation with moderate hypoxemia (worsening ABGs)

P Up-regulate Oxygen Therapy Protocol (3 L/min nasal cannula). Add Aerosolized Medication Protocol; up-regulate Bronchopulmonary Hygiene Therapy Protocol (2 mL 10% acetylcysteine with 0.2 mL albuterol q6h followed by C&DB and PD to both upper lobes). Add supervised use of flutter valve 2 times per shift. Request repeat CXR. Continue to monitor and reevaluate.

Respiratory Assessment and Plan

S “I’m breathing much better.”

O No obvious respiratory distress; no spontaneous cough; strong, nonproductive cough on request; vital signs: BP 135/88, HR 80, RR 14, T normal; bilateral crackles in the lung apices; Spo2 91%; ABGs: pH 7.44, Paco2 34,  23, Pao2 71

23, Pao2 71

• Adequate bronchial hygiene status (nonproductive cough, absence of rhonchi, crackles expected in lung fibrosis)

P Discontinue Oxygen Therapy Protocol. Recheck Spo2 on room air (“spot check”) in 1 hour. Discontinue Bronchopulmonary Hygiene Therapy Protocol. Instruct patient in trial use of Combivent (albuterol/ipratropium) MDI. Reevaluate the patient when he is off all therapy modalities but on self-administered MDI in am; then sign off.

Discussion

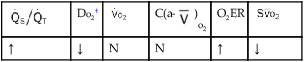

Respiratory care practitioners (RCPs) who work in the Southwest, where coccidioidomycosis is endemic, would probably anticipate this diagnosis in the patient with bilateral pulmonary infiltrates, swollen tender joints, and the skin rash typical of this lesion. Others could not be blamed if they missed this potential diagnosis until the coccidioidal skin test came back positive and the sputum fungal smear demonstrated the presence of the coccidioidomycosis organism. In this case, the patient demonstrated the clinical manifestations associated with the following two anatomic alterations of the lungs: Increased Alveolar-Capillary Membrane Thickness (e.g., bilateral fibrosis and calcification; see Figure 9-10) and Excessive Bronchial Secretions (e.g., cough, sputum, and rhonchi; see Figure 9-12).

)

)

)O2, Arterial-venous oxygen difference; DO2, total oxygen delivery; O2ER, oxygen extraction ratio;

)O2, Arterial-venous oxygen difference; DO2, total oxygen delivery; O2ER, oxygen extraction ratio;  , pulmonary shunt fraction;

, pulmonary shunt fraction;  , mixed venous oxygen saturation;

, mixed venous oxygen saturation;  , oxygen consumption.

, oxygen consumption.

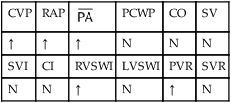

, mean pulmonary artery pressure; PCWP, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure; PVR, pulmonary vascular resistance; RAP, right atrial pressure; RVSWI, right ventricular stroke work index; SV, stroke volume; SVI, stroke volume index; SVR, systemic vascular resistance.

, mean pulmonary artery pressure; PCWP, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure; PVR, pulmonary vascular resistance; RAP, right atrial pressure; RVSWI, right ventricular stroke work index; SV, stroke volume; SVI, stroke volume index; SVR, systemic vascular resistance.

22, and Pa

22, and Pa 21, and Pa

21, and Pa 23, and Pa

23, and Pa