CHAPTER 3 Fundamental Principles of Herbal Medicine

THE EVIDENCE BASE FOR BOTANICAL MEDICINE

Herbal medicine is undergoing rapid evolution as divergent streams of thought meet to redefine it in a modern clinical context. Many Western herbalists and naturopathic physicians share the concern that the mainstreaming of herbal medicine threatens to uproot it from its classical foundation; yet, practitioners are also concerned with having solid scientific validation that the products they recommend, or which their patients might already be using, meet basic standards of safety and efficacy. 1 2 3 4 Interestingly, patients are often more interested in anecdotal evidence of safety and risk in contrast to practitioners who are more likely to want detailed and objective evidence of benefit, safety, and risk.5 There is a tremendous need for a comprehensive way to evaluate herbal medicine efficacy and safety while integrating the concerns and experiences of all of the partners in health care: medical doctors and scientists, traditional practitioners, and those taking herbal medicines both for self-care and as patients.

This chapter proposes an integrative model of evidence-based herbal medicine that allows an intelligent synthesis of the various possible forms of data in the evaluation of botanical medicines, in order to include traditional evidence, scientific findings, and expert consensus based on clinical observation. This chapter also discusses the evidence upon which this text is based. In its broadest and most liberal interpretation, evidence-based medicine (EBM) can embody an ideal fusion of “clinical and laboratory research data with human experience,” as suggested by herbalist Simon Mills, rather than the reductionist, prepackaged mind-set that it has been accused of engendering.6 An integrative model of presenting evidence can be seen in the monograph collections of the European Scientific Cooperative on Phytotherapy (ESCOP), the World Health Organization (WHO), and the American Herbal Pharmacopoeia (AHP), all of which acknowledge multiple levels of evidence including traditional use, clinical applications, and relevant science.

WHAT IS EVIDENCE-BASED MEDICINE?

The concept of EBM was first articulated in mid-nineteenth century Paris, and perhaps earlier.7 Described more recently as “the conscientious, explicit and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients,”7 EBM has been widely adopted in conventional medical circles as a hierarchic methodologic model of evaluating and ranking evidence for the determination of what is considered the best and most objective clinical practice. EBM as a packagable product-concept has become big business in medicine—a profitable host of commodities that include national conferences, hand-held computers that can be taken into patient consultations and programmed to generate EBM protocol for patients on the spot, books and journals, undergraduate and postgraduate training programs, and Web-based courses.7 Centers for the study of EBM have been established, as have extensive databases.7

Yet, responses to EBM as a medical paradigm based solely on external, objective evidence to the exclusion of the practitioner’s clinical judgment and experience have been highly equivocal, with widely varying criticisms ranging from “evidence-based medicine being old hat” to it being a “dangerous innovation, perpetrated by the arrogant to serve cost-cutters and suppress clinical freedom.” EBM has been “criticized for the inappropriateness of much evidence and its application to clinical practice, for logical inconsistencies, for potentially reducing the role of clinical judgment, for difficulties integrating into everyday professional practice, and for cultural bias.”8 EBM has been critically called “cookie-cutter” medicine, systematizing patient treatments according to specified protocol.9 Ironically, this appears to be a backward step in light of patients’ increasing demands for greater individual attention in medical care. Accusations of EBM being a cost-cutting measure are based upon the belief that streamlining diagnoses and treatments will represent cost savings to managed care organizations. 7 8 9

Practitioners naturally want to provide their patients with the best options. Many believe that relying solely on external, quantified evidence will relieve them of the burden of responsibility (or culpability) inherent in exercising individual clinical judgment. However, removing subjective observation and judgment entirely from clinical decision making requires objectifying and homogenizing patients. John Astin, PhD, writing in Academic Medicine, states

Decisions in medicine, irrespective of how much objective evidence we gather, always involves the weighing of probabilities.… To suggest that randomized controlled trials, meta-analyses and clinical practice guidelines will eliminate the need for clinical judgment is to misrepresent the realities of clinical medicine (both CAM and conventional). If medicine could be purely evidence-based (which is highly debatable both practically and financially), then in theory medical care…could essentially be administered by computers and computer algorithms.2

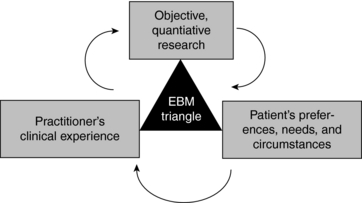

EBM proponents such as David Sackett suggest that the concept of EBM has been misinterpreted to be a one-dimensional orthodoxy based solely on objective, quantitative research methodologies, and that it is actually a much broader model than has been typically conveyed, with external evidence being only one of three important aspects of EBM.7 The other arms of EBM are the patient’s preferences, needs, and circumstances, and the practitioner’s clinical experience (Fig. 3-1).

Sackett’s description of EBM demonstrates its potential to serve as an integrative model:

The practice of evidence-based medicine means integrating individual clinical expertise with the best available external clinical evidence from systematic research. By individual clinical expertise we mean the proficiency and judgment that individual clinicians acquire through clinical experience and clinical practice. Increased expertise is reflected in many ways, but especially in more effective and efficient diagnosis and in the more thoughtful identification and compassionate use of individual patients’ predicaments, rights, and preferences in making clinical decisions about their care. By best available clinical evidence we mean clinically relevant research, often from the basic sciences of medicine, but especially from patient centered clinical research.… Without clinical expertise, practice risks becoming tyrannized by evidence, for even excellent external evidence may be inapplicable to or inappropriate for an individual patient. Without current best evidence, practice risks becoming rapidly out of date, to the detriment of patients.… External clinical evidence can inform, but can never replace, individual clinical expertise, and it is this expertise that decides whether the external evidence applies to the individual patient at all and, if so, how it should be integrated into a clinical decision.7

According to this, evidence-based medicine need not be restricted to reductionist forms such as RCTs and meta-analyses as some suggest (Box 3-1, Fig. 3-1). At its best, it is a “triangulation of knowledge from education, clinical practice, and the best research available for a given condition or therapy.”9

BOX 3-1 Research Methods for Beginners

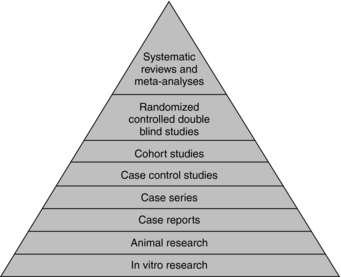

For those unfamiliar with research jargon, here is a brief overview of research methodologies and terminology. Research methods are categorized hierarchically in order of highest to lowest value of objectivity and reliability of the varying levels of evidence. The “evidence pyramid” is one such scheme for classifying research methods (Fig. 3-2).

SUPPORTING EVIDENCE FOR BOTANICALS DISCUSSED IN THIS TEXT

Scientific Evidence

Scientific data included in this book may fall into any of the following categories:

Problems with Conventional Research Methodologies for Botanical Therapies

Not all CAM therapies (i.e., prayer, homeopathy) are expected to stand up to classic methods of safety and efficacy testing. However, because herbs contain pharmacologically active substances, there is an implicit expectation that if herbs “really work” they should be able to measure up to the standards set for conventional drugs. Although this is theoretically sound, it is not reasonable in practice: Whole herbs are not the same as isolated drugs, nor are they applied as such by botanical medicine practitioners. A distinction can be made for single isolated active ingredients derived from botanicals, which are much more like pharmaceutical drugs than they are herbal products. RCTs for herbal products, in which all study group participants receive the same treatment are by definition given in a model antithetical to the way herbs are actually applied clinically by herbalists, wherein choice of herbs, formulation, and dosage are tailored specifically to the patient’s unique needs.6,9 There is also frequently a difference in the form of products used in clinical trials compared with those used by professional botanical medicine practitioners. Typically, botanical medicines are prescribed as multi-ingredient formulas, or as single herbs, in whole plant or whole plant extract forms that are most appropriate to the individual herb and specific patient. For most herbs, the biological activities of the constituents have not yet even been well characterized.10

Experience has shown that there are real benefits in the long-term use of whole medicinal plants and their extracts, since the constituents in them work in conjunction with each other. However, there is very little research on whole plants because the drug approval process does not accommodate undifferentiated mixtures of natural chemicals, the collective function of which is uncertain. To isolate each active ingredient from each herb would be immensely time-consuming at unsupportable cost, and is almost impossible in the case of preparations.11

Limits of Research and Research Biases

Implicit in relying upon the results of RCTs and other classic trials is the belief that they represent unbiased analyses. This may be a mistaken assumption. Even the RCT, the gold standard of research methodologies and one of the most reliable methodologies for limiting study biases, is not impervious to bias and is not without limitations.12 Methodologic features of RCTs, including trial quality, have been shown to influence effect sizes; and some researchers believe that eliminating the psychological component of clinical care from trials and minimizing placebo effect may cause studies to bear little resemblance to clinical practice.13,14

Politics also influences the choice of which studies get funded; what questions are asked; and whether, where, and how outcomes are published.15 Limited financial incentive on the part of pharmaceutical companies and researchers to investigate herbal products, particularly whole herbs, is due in part to the limited patentability of botanicals, and leads to fewer funding opportunities.16,17 Publication bias on the part of medical journals also has recently been raised as a significant concern. Additionally, there may be negative biases in the publication of case reports, with emphasis placed on the negative side effects of botanicals.3 John Astin, MD writing on CAM, states that the “approach of selectively citing one negative article while failing to cite any of the positive systematic reviews or meta-analyses is the antithesis of evidence-based medicine. It is, in short, opinion based medicine.”2 He states further that “The failure to cite such evidence contributes to a very misleading picture of the state of the scientific evidence base underlying CAM.”2

Nonetheless, in spite of the billions of dollars of herbal products sold in the United States alone, there are negligible reports of adverse herbal events compared with the volume of reported adverse drug events. In Europe, where millions of units of herbal products are sold and market surveillance and adverse events reporting systems are well established, there too are an amazingly small number of adverse reports.8 A major concern expressed about herbal medicine is the questionable safety of botanical medicines in pregnancy. Although indeed many are not to be used in pregnancy because of uncertainty about their safety, more than 90% of medications approved since 1980 have not been properly tested for mutagenicity or teratogenicity.18 Further, a growing body of evidence suggests that only 20% to 37% of conventional medical practices that are commonly accepted and used across a broad range of medical specialties are predicated on evidence from RCTs. Coronary bypass surgery was used for over 20 years before it was subjected to clinical trials.16,19,20 Although these statistics do not justify lack of evidence for nonconventional therapies, and do not negate the necessity for reliable clinical evidence, it does illustrate that there are sometimes double standards influencing attitudes about nonconventional therapies, and that there may at times be a suspension of common sense in pursuit of the holy grail of evidence (Box 3-2).

BOX 3-2 A Satirical View of EBM

Parachute Use to Prevent Death and Major Trauma Related to Gravitational Challenge: Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials

Design: Systematic review of randomized controlled trials.

Study selection: Studies showing the effects of using a parachute during free fall.

Main outcome measure: Death or major trauma, defined as an injury severity score >15.

Results: We were unable to identify any randomized controlled trials of parachute intervention.

Expert Consensus

Well into the early twentieth century, observational studies were considered an important source of medical evidence, declining in perceived value only over the past 20 years.12 Clinical decision making in medicine was based on observation, personal experience, and intuition.12 Even the randomized controlled clinical trial (RCT) is only 50 years old and has been established as the definitive method of testing new drugs only since the 1980s.21

Although herbal medicine is frequently “dismissed by the orthodoxy as a fringe activity,”6 there are actually thousands of well-trained, highly knowledgeable and experienced clinical Western herbalists in numerous countries—England, Scotland, Germany, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and the United States, to name a few. In Europe, particularly in Germany, phytotherapy is an accepted part of medical practice. Botanical experts are trained as either part of medical education if they are physicians, or in recognized botanical medicine educational programs with consistent curricula. In the United States, 13 states currently recognize naturopathic physicians who have graduated from accredited 4-year naturopathic colleges and passed their medical boards as legitimate physicians whose scope of practice includes botanical medicine. Over the past decade, a number of physicians have also gained significant experience in the clinical use of herbs. Although anecdotal evidence has largely been dismissed as invalid, the consensus of a large body of experts is entirely valid.

A large collective body of knowledge from contemporary clinical practitioners provides compelling evidence for the use of herbal medicines. Case studies (n = 1 studies), case series, uncontrolled trials, observational reports, and outcome-based studies all contribute important information to the dialogue on botanicals, ranging from establishing clinical effects that merit further study to providing clinical insights that corroborate traditional uses with modern pharmacologic effects.22,23 “Case study research provides a useful tool for investigation of unusual cases or therapies for which effectiveness data are lacking and for preliminary investigation of any factor that may influence patient outcome.” Qualitative research methods need to be developed further to fully evaluate the efficacy and safety of nonconventional therapies.21 Collaboration between conventionally trained researchers and traditional and medical herbalists to systematically document herbalists’ clinical use of botanical medicines is a rich and yet untapped area for botanical medicine research.

Traditional Evidence

Historical information referred to in this text is largely derived from classical botanical medicine texts, treatises and herbals, pharmacopoeias, monographs, and academic books on the history of botanical medicines. These appear in the references corresponding to individual chapters. Herbalist Kerry Bone best explains traditional use:

Traditional use occurs in the context of a traditional medicine system. This healing system may have evolved over thousands of years and be part of a great culture, or it may be part of a smaller or more primitive system. The important point is that traditional use is the refined knowledge of many generations, carefully evaluated and re-evaluated by many practitioners of the craft. It is not just the anecdotal accounts of a few practitioners.24

Bone defines folk use “as small-scale use; often in an isolated context.… Folk use should therefore not be confused with traditional use. That is not to say that folk use is without value. More that it should be placed in the context of the hypothetical rather than the definite.”24

REFERENCES USED IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF THIS TEXT

The following were considered acceptable forms of references for inclusion in this text:

Boxes 3-3 and 3-4 give a complete list of botanical medicine texts, monographs, and databases consulted for this book.

BOX 3-3 Integrative Medicine Texts, Herbal Texts, and Herbal Monographs Referenced in the Book

Barrett M. Handbook of Clinically Tested Remedies, 1 and 2, 2004, Haworth Press, New York

Barton S. Clinical Evidence. London: BMJ Publishing Group, 2001.

Bruneton J. Pharmacognosy. Paris: Technique and Documentation, 1999.

Bruneton J. Toxic Plants Dangerous to Humans and Animals. Paris: Technique and Documentation, 1999.

Blumenthal M. The ABC Clinical Guide to Herbs. Austin: American Botanical Council, 2003.

Blumenthal M, Busse W, Goldberg A, et al. The Complete German Commission E Monographs Therapeutic Guide to Herbal Medicines. Austin: American Botanical Council, 1998.

Blumenthal M, Goldberg A, Brinckmann J. Herbal Medicine: Expanded Commission E Monographs. Newton, MA: Integrative Medicine Communications, 2000.

Bone K. A Clinical Guide to Blending Liquid Herbs. St. Louis: Churchill Livingstone, 2003.

Bone K. Clinical Applications of Ayurvedic and Chinese Herbs. Queensland, AU: Phytotherapy Press, 2000.

European Scientific Cooperative on Phytotherapy (ESCOP). ESCOP Monographs: The Scientific Foundation for Herbal Medicinal Products, ed 2. New York: Thieme, 2003.

Evans WC. Trease and Evans’ Pharmacognosy. London: Saunders, 1998.

Felter HW, JU Lloyd. King’s American Dispensatory, vols 1 and 2, 1898, ed 18. Sandy Oregon: Eclectic Medical Publications, 1983.

Hoffmann D. Medical Herbalism: The Science and Practice of Herbal Medicine. Rochester, VT: Healing Arts Press, 2003.

Kligler B, Lee R. Integrative Medicine: Principles for Practice. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2004.

Kohatsu W. Complementary and Alternative Medicine Secrets. Philadelphia: Hanley & Belfus, 2002.

Kraft K, Hobbs C. Pocket Guide to Herbal Medicine. New York: Thieme, 2004.

LowDog T, Micozzi M. Women’s Health in Complementary and Integrative Medicine: A Clinical Guide. St. Louis: Elsevier, 2004.

McGuffin M, Hobbs C, Upton R, et al. American Herbal Products Association Botanical Safety Handbook. Boca Raton: CRC Press, 1997.

McKenna DJ, Jones K, Hughes K, et al. Botanical Medicines: The Desk Reference for Major Herbal Supplements. New York: Haworth Press, 2002.

Mills S, Bone K. Principles and Practice of Phytotherapy. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2000.

Moerman D. Native American Ethnobotany. Portland: Timber Press, 2000.

O’Dowd MJ. The History of Medications for Women: Materia medica woman. New York: Parthenon Publishing Group, 2001.

Rakel D. Integrative Medicine. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2003.

Rotblatt M, Ziment I. Evidence-Based Herbal Medicine. Philadelphia: Hanley & Belfus, 2002.

Upton R. American Herbal Pharmacopoeis and Therapeutic Compendium Series. Santa Cruz, CA: American Herbal Pharmacopoeia, 2004.

Weiss R, Fintelmann V. Herbal Medicine, ed 2. New York: Thieme, 2000.

Wichtl M. Herbal Drugs and Phytopharmaceuticals: A Handbook for Practice on a Scientific Basis. Stuttgart: Medpharm, 2004.

BOX 3-4 Internet Databases Consulted in This Text

No Author, n.d. http://www.cabi.org/

No Author, n.d. http://www.cinahl.com/

No Author, n.d. http://www.herbmed.org

No Author, n.d. http://www.mcphs.edu/

No Author, n.d. http://www.mdconsult.com/

No Author, n.d. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/

No Author, n.d. http://www.naturalstandard.com/

IS THERE ADEQUATE EVIDENCE FOR BOTANICAL MEDICINES?

Although it is frequently stated that botanical medicines are poorly studied, a quick examination of a comprehensive database (e.g. Ovid) should dispel that myth. In addition to clinical studies, there are numerous in vitro and in vivo human tissue, cell, and animal studies on herbal products and isolated constituents.8 In Europe, clinical research into herbal medicine has been established for decades.17 With the establishment of NCCAM, the priority for herbal research has continued to grow in the United States. Although there are a limited number of RCTs for most herbs, those that have been conducted should establish a compelling argument for the efficacy of herbal medicines. Efficacy studies and meta-analyses are growing in number and include positive reports in the Cochrane Collaboration on ginkgo for cognitive impairment and dementia, echinacea for cold treatment, St. John’s wort for treatment of mild to moderate depression, and feverfew for the treatment of migraines, and RCTs for St. John’s wort for treatment of mild to moderate depression, kava for anxiety, chaste tree berry for PMS, and horse chestnut for venous insufficiency, among others.8,24

It is also important to remember that few botanical approaches have been disproved or proved dangerous.2 As conventional medicine moves toward a more integrated model of health care that incorporates herbal medicines, and as botanical medicine practitioners increasingly work with medical professionals, there will be an inherent need to blend languages and approaches to create a useful and mutually respectful paradigm. Change will have to be reflected not only in clinical and educational settings but also in research models. An inclusive, holistic interpretation of EBM allows the possibility of it being used as an ideal model incorporating the best available objective evidence (scientific, traditional, ethnobotanical, etc.) with practitioner experience and patient preferences and circumstances.

CONSTITUENTS OF MEDICINAL PLANTS

SYNERGY AND VARIABILITY

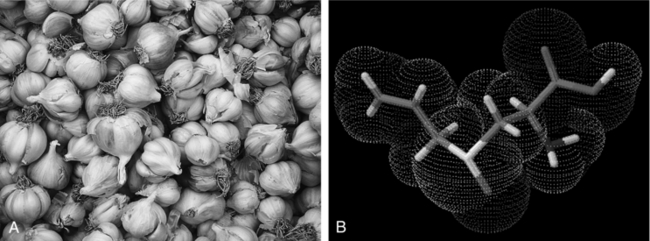

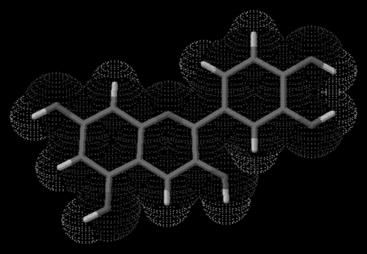

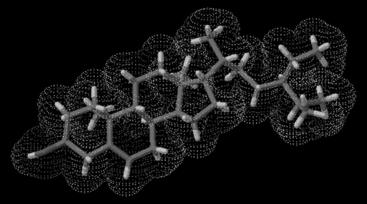

A living plant contains myriad compounds that work synergistically to protect the plant from harm and carry out all the processes of its metabolism. Interestingly, many of these molecules have similar functions in plants and humans. For instance, the berberine in Mahonia aquifolium (Oregon grape; Fig. 3-3) is an example of an antimicrobial compound that protects against fungal and bacterial infection in both plants and humans. Another example is the class of molecules known as flavonoids, which occur in all green plants. In the chloroplasts, flavonoids act as primary antioxidants to protect the delicate light-harvesting compounds from ultraviolet and free radical damage. In the human body, these same compounds act as antioxidants, anticarcinogens, and anti-inflammatories by virtue of their radical quenching activities.

Phytochemical variability is an important concern for the herbal practitioner. We must keep in mind that the chemical profile of a living plant is a system that constantly adapts to conditions in the environment. For example, seasonal variability is demonstrated in Taraxacum officinalis (dandelion) by levels of the therapeutic oligosaccharide inulin (a soluble fiber) known to range from 2% to 40% in spring and fall roots, respectively. In this same herb, the levels of sesquiterpene lactones (digestive bitters) vary tremendously among the seasons, accounting for the sweetness of early spring leaves as opposed to their pronounced bitterness later in the summer. Along with seasonal variation, the herbalist must consider phytochemical variations owing to time of day, rainfall, soil composition, growing location, companion plants, fungi, and insects, developmental stage of the herb, and traditionalists might argue, phases of the moon, vitality of the plant, and energetic or spiritual relationships between the plant and the people who harvest and use its medicine. In addition, many species have chemotypes, or significantly differing chemical races, which may be difficult to distinguish visually. Therefore, proper growing conditions and harvesting time and techniques largely determine the efficacy of individual herb products, and any assessment of product quality must consider these variables.

CONSTITUENT CLASSIFICATION

Herbal Constituent Categories

The main categories of herbal constituents are:

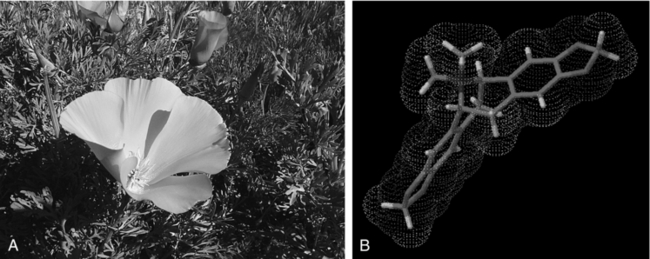

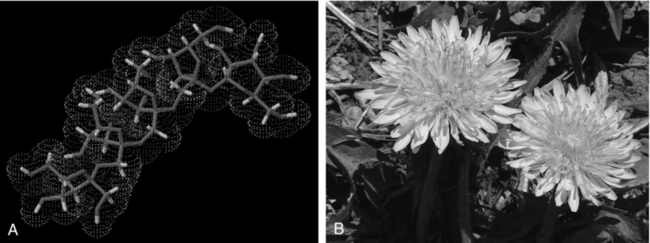

Figure 3-4 A, Inulin. (Courtesy Lisa Ganora.) B, Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale).

Photo by Martin Wall.

SOLUBILITY

The question often arises concerning whether the herbalist should use a water extraction (infusion, decoction, tea, or soup) versus an alcohol extraction (tincture, extract, or fluid extract) or some other type of material. There is a definite difference between these preparations; one brings a different range and concentration of constituents out of a plant than does another. Much of this difference is based on the solubility of the constituents within the herb. The solubilities of isolated constituents can be found in tables, but those values are subject to change within the matrices of different plants. In fact, they can vary considerably. Solubility is influenced by many factors, including pH, heat, concentration, and the presence of salts, tannins, and various other constituents. It can be difficult to predict, and practical experience, organoleptic evaluation, and analytical analysis must be used to determine which extraction methods are most efficacious for which compounds (see Forms of Administration).

The list given in Table 3-1 is oversimplified; there are numerous exceptions. It should be kept in mind that most compounds have at least some degree of solubility in water, alcohol, and oil menstrua. It is often more helpful to think of solubility on a continuum, rather than in absolute terms such as soluble or insoluble. For example, we may think of certain compounds as being only alcohol soluble or only oil soluble; but a small concentration of these molecules can dissolve in water as well.

THE ACTIONS OF HERBS

GENERAL ACTIONS

Adaptogen

Soviet scientists coined the term adaptogen in 1964 to describe herbs that increase the body’s nonspecific resistance and vitality, helping the body adapt to and defend against the effects of various stressors and increase work capacity and efficiency and ability to concentrate. (See Chapter 7 for a comprehensive discussion of adaptogens.)

For an herb to be classified as an adaptogen it must:

Adaptogens appear to moderate the stress response in the following ways:

The specific mechanisms of adaptogenic activity have not yet been entirely elucidated, but some generalizations can be made. Pretreatment with adaptogens appears to alter endocrine functions of the pituitary adrenal gland axis. Regular pretreatment with adaptogens causes a normalization of stress hormone levels and a generally decreased predisposition to stress. Other body systems also respond to the direct or indirect regulatory influences of adaptogens. For example, adaptogens have been shown to influence the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA axis), to confer immunostimulatory actions, and to activate cognitive functions. A number of herbs can be described as adaptogens (Box 3-5 and Fig. 3-11), based upon both clinical and in vitro research.

Alterative

Alteratives “alter” the body’s metabolic processes, improving a range of functions from nutrition to elimination (Box 3-6 and Fig. 3-12). Folk healing traditions sometimes invoke the concept of “blood cleansing,” which, although hinting at much, is technically inaccurate, as blood does not require “cleansing.” Traditionally, these herbs may have been used, along with bitters (see the following) for spring cleansing, or when there was infection or skin disease. Many of the herbs with this action help the body eliminate waste through the kidneys, liver, lungs, or skin. Some work by stimulating digestive function, some are immunomodulators, whereas others work through unknown mechanisms of action. Immunologic research on certain secondary plant products, especially saponins, has led to some interesting suggestions for the basis of alterative action; however, the specifics of plant activity are the result of the way the whole plant works upon the human body, not simply specific active ingredients. Alteratives can be used as supportive therapy in many diverse conditions, and should be considered first for cases of chronic inflammatory or degenerative diseases. These include skin diseases, various types of arthritis, and a wide range of autoimmune problems.

Analgesic

Analgesics (Box 3-7 and Fig. 3-13) relieve pain. Mild analgesic herbs are referred to as anodynes. Analgesic activity may be owing to anti-inflammatory action (Dioscorea villosa) or central effects (e.g., Piscidea piscipula, Piper methysticum) and can range from mild to strong effects. Most of the strongest herbal analgesics are no longer legally available for herbal prescription, such as opium poppy extracts and cannabis products. The action of analgesics is considered cooling.

Antiemetic/Antinauseant

These are herbs that alleviate nausea and prevent or reduce vomiting (Box 3-8 and Fig. 3-14). This property is generally the result of the presence of volatile oils in the plant, many of which have antispasmodic effect. They are relaxing to the digestive system, and in some cases have a direct action on the medulla (vomiting center) of the brain. They are useful in the treatment of morning sickness, hyperemesis gravidarum, motion sickness, chemotherapy-induced nausea, and nausea related to colds and general stomach upset.

Anti-Inflammatory

Anti-inflammatory herbs (Box 3-9 and Fig. 3-15) relieve inflammation, largely without the side effects of steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. They are beneficial for relieving pain and discomfort, but offer the greatest benefit when used in combination with other remedies to address the underlying problems causing inflammation. Inflammation is a normal physiologic response to infection and other pathologies. Through localized biochemical and tissue changes, the inflammatory reaction facilitates healing. Sometimes however inflammation itself becomes so intense that it becomes part of the problem, and herbal remedies can be used to provide some measure of relief without full suppression. This can help to further facilitate the healing process, allowing the body to respond normally but without undue suffering or damage to the patient.

Anti-inflammatory herbs can be classified in terms of the body system (Table 3-2) or tissue for which they are most appropriate or by their pharmacologic mode of action. There are four primary categories of anti-inflammatory herbs:

| BODY SYSTEM | EXAMPLES OF HERBS |

|---|---|

| Circulatory | Tilia platyphyllos, Crataegus spp., Aesculus hippocastanum, and Achillea millefolium |

| Digestive | Matricaria recutita, Dioscorea villosa, Glycyrrhiza glabra, Hydrastis canadensis, Calendula, and Mentha piperita. Demulcent remedies rich in mucilage, such as Althaea officinalis, can have the localized effect of reducing inflammation through contact soothing. |

| Urinary | Solidago virgaurea, Zea mays |

| Reproductive | Alchemilla arvensis, Caulophyllum thalictroides |

| Musculoskeletal | Salix spp., Filipendula ulmaria, Populus tremuloides, and Betula spp., Harpagophytum procumbens, Actaea racemosa, Tanacetum parthenium, and Dioscorea villosa |

| Nervous | Hypericum perforatum |

| Skin | Calendula officinalis, Hypericum perforatum, Commiphora molmol, Hydrastis canadensis, Arnica montana, Stellaria media, and Plantago major |

Salicylate-Containing Anti-Inflammatory Herbs

Numerous herbs contain salicylic acid salts, the molecule from which aspirin was developed. These are most useful for musculoskeletal inflammations, such as arthritis. Herbs containing significant quantities of salicylic acid have a marked anti-inflammatory effect, without posing the dangers to the stomach associated with aspirin. In fact, Filipendula ulmaria, rich in salicylates, has been used to staunch mild stomach bleeding. Other plants rich in these constituents include Salix spp., Gaultheria procumbens, Betula spp., and Viburnum prunifolium.

Antimicrobial

Antimicrobial herbs (Box 3-10) help the body to destroy or resist pathogenic microorganisms, including bacteria, fungi, and viruses. It would be a mistake to attempt an overarching generalization about mechanisms of action for herbal antimicrobials. The use of the term antimicrobial is a description of expected outcome, rather than a description of mechanisms. Antimicrobial effects may be related to direct interactions with pathogens or indirectly mediated via the herb’s interaction with the immune system. As examples of the diversity of mechanisms involved (Table 3-3), consider the following: Melaleuca alternifolia (tea tree) contains an oil rich in terpinene-4-ol that directly interferes with a pathogen’s metabolism, thus killing it. Other herbs rich in volatile oils also work directly to kill microorganisms. Examples include Allium sativum, Thymus vulgaris, and Eucalyptus spp. Echinacea directly stimulates the body’s own immune response, and thus is often an effective antimicrobial agent. Vaccinium macrocarpon (cranberry juice) blocks the adhesion of uropathogenic E. coli to the walls of the bladder, thus offering a useful treatment for cystitis.

| BODY SYSTEM | EXAMPLES OF HERBS |

|---|---|

| Urinary | Arctostaphylos uva-ursi, Achillea millefolium |

| Reproductive | Calendula officinalis, Echinacea spp., Allium sativum, Thymus vulgaris |

| Nervous | Hypericum perforatum, Melissa officinalis |

Antispasmodic/Spasmolytic

Antispasmodic herbs (Box 3-11 and Fig. 3-16) relieve muscle tension and spasm, both in the musculoskeletal system and the smooth muscle of the hollow organs (i.e., bladder, uterus, stomach, intestine, gallbladder) (Table 3-4). The term antispasmodic is synonymous with spasmolytic. Uterine antispasmodics, which typically work on the bladder as well, are listed separately under gynecologic and obstetric actions. Antispasmodics usually have peripheral action and generally are not sedating.

TABLE 3-4 Body System Affinities with Antispasmodics/Spasmolytic

| BODY SYSTEM | EXAMPLES OF HERBS |

|---|---|

| Cardiovascular | Leonurus cardiaca, Viburnum opulus, Actaea racemosa |

| Digestive | Matricaria recutita, Viburnum opulus, Viburnum prunifolium, Valeriana officinalis, Humulus lupulus, Mentha piperita, Salvia officinalis, Foeniculum vulgare, Dioscorea villosa |

| Urinary | Viburnum opulus, Viburnum prunifolium, Dioscorea villosa, Piper methysticum |

| Reproductive | Viburnum opulus, Viburnum prunifolium, Dioscorea villosa, Actaea racemosa |

| Musculoskeletal | Piper methysticum, Viburnum opulus, Viburnum prunifolium, Lobelia inflate, Valeriana officinalis, Scutellaria lateriflora, Actaea racemosa |

Astringent

The basic action of astringents (Box 3-12 and Fig. 3-17) is to tonify or tighten tissue. They are sometimes called styptics when applied externally to stop bleeding, and antihemorrhagics when used for internal bleeding. Astringent action results from a diverse group of complex chemicals called tannins or gallotannins that share chemical and physical properties. All members of this group have phenolic characteristics, are soluble in water, and have molecular weights ranging from 500 to 3,000. There are two groups: derivatives of flavonols called condensed tannins and the more important hydrolyzable tannins. The name tannin comes from the use of these constituents in the tanning industry. They have the effect of precipitating, or denaturing, protein molecules. They also precipitate starch, gelatin, alkaloids, and salts of heavy metals. One of the few incompatibilities found when making herbal medicines is that astringent, tannin-rich remedies create precipitates with herbs high in alkaloids. This alteration of protein is how animal skin is turned into leather. In other words, astringents produce a kind of temporary leather coat on the surface of tissue. Because of this activity, tannins have a number of therapeutic benefits. They:

Astringents have a role in a wide range of problems in many parts of the body (Table 3-5) but are of great importance in wound healing and conditions affecting the digestive system. In the gut, they reduce inflammation, improve symptoms of diarrhea, and are widely used in various diseases of digestion. However, long-term use as medicine or too much tea in the diet can be deleterious to health, as this will eventually inhibit proper food absorption across the gut wall.

| BODY SYSTEM | EXAMPLES OF HERBS |

|---|---|

| Digestive | Quercus spp., Hamamelis virginiana, Geranium maculatum, Hydrastis canadensis, Salvia officinalis |

| Urinary system | Equisetum arvense, Achillea millefolium |

| Reproductive | Alchemilla arvensis, Hydrastis canadensis, capsella burso-postoris, Achillea millifolium |

| Skin | Achillea millefolium, Hamamelis virginiana, Plantago major, Quercus spp. |

Bitter

Quite simply, these are remedies that have a bitter taste, although their actions are anything but simple. These herbs (Box 3-13 and Fig. 3-18) can range from mildly bitter-tasting remedies, for example, Achillea millefolium and Taraxacum officinale leaf, to profoundly distasteful herbs, such as Ruta graveolens and Artemisia absinthium. The constituents that contribute bitterness to an herb are described as bitter principles. Taste is a phenomenon of chemoreception; a range of molecular structures share the bitter property. Great diversity and complexity are found among these bitter principles, but it appears that they all work in a similar way by triggering a lingual sensory response. Examples of such constituents include monoterpenes, iridoids, sesquiterpenes, and alkaloids. Absinthin, found in plants of the genus Artemisia, such as Artemisia absinthium, is so bitter it can be tasted at dilutions of 1:30,000! A reflex is stimulated by bitter taste, directed by the nerves to the central nervous system. From there, a message goes to the gut, giving rise to the release of the digestive hormone gastrin. This in turn leads to a whole range of effects, all of value to the digestive process. Among the many actions of bitters, they:

The tonic effects of these remedies go beyond specific digestive hormone activity. As digestion and assimilation of food is basic to health, bitter stimulation can often fundamentally affect health far beyond the simple mechanics of digestion (Table 3-6). In general, these benefits do not occur unless the bitter herb is tasted, so they should not be given in a capsule intended to help the patient avoid the unpleasant taste.

| BODY SYSTEM | EXAMPLES OF HERBS |

|---|---|

| Cardiovascular | Humulus lupulus, Valeriana officinalis |

| Digestive | Artemisia vulgaris, Berberis vulgaris, Centaurium erythraea, Chelidonium majus, Gentiana lutea, Hydrastis canadensis, Humulus lupulus |

| Reproductive | Leonurus cardiaca, Artemisia vulgaris, Achillea millefolium |

| Nervous | Gentiana lutea, Artemisia vulgaris |

| Skin | Taraxacum officinalis, Arctium lappa |