Functional disorders

There are many neurological patients with neurological symptoms and signs that are not due to underlying neurological abnormalities but reflect a psychological problem. In others, there is an elaboration of a neurological abnormality so that the signs elicited extend beyond the distribution of the neurological lesion or are out of proportion with the neurological lesion.

Non-epileptic attacks or pseudoseizures

Non-epileptic attacks or pseudoseizures are episodes that appear superficially to be seizures. They may be continuous and mimic status epilepticus; indeed, 50% of patients admitted to intensive care units with status epilepticus have been found to have pseudoseizures. In many patients, the attacks can readily be distinguished from epileptic seizures: they often include semi-purposeful thrashing (‘it took five men to keep me down’); patients remain pink throughout and may flush, but do not become cyanosed; respiration is normal; they do not bite their tongues; incontinence is rare; and recovery is usually quick. There are some patients where it is more difficult to be certain. To establish the diagnosis, an EEG during the attack needs to be demonstrated to be normal. The attacks tend to occur more often when medical and nursing staff are at hand and obtaining an EEG during an attack is usually more readily achieved than in epileptic seizures. Measurement of prolactin following a seizure can also be useful, as this is elevated after a tonic-clonic epileptic seizure.

It is uncertain how many patients with pseudoseizures also have epileptic seizures.

Paralysis

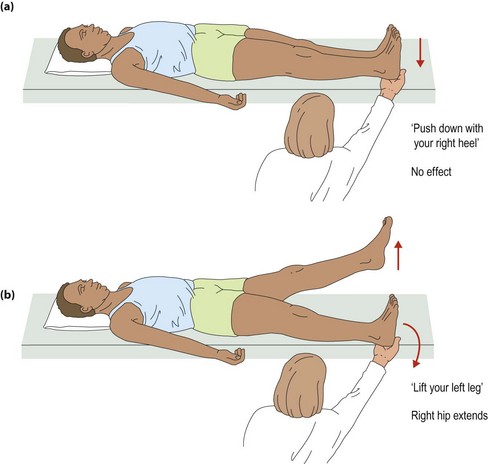

In patients with non-organic weakness, there is usually an inconsistency in the power of the limb on formal testing and when the patient uses it. Examples include patients who can swing their legs up only on the bed when getting onto it but cannot lift the legs against gravity on formal testing; or patients who can stand with legs slightly flexed at the knees supporting their own weight but who cannot walk. There is usually a characteristic collapsing weakness. There are several manoeuvres that can bring this out, such as Hoover’s sign (Fig. 1), or the movement found when testing coordination, which is not obtained on testing power.

Sensory loss

Most patients with organic sensory loss have an incomplete loss, which affects some modalities more than others and accords with a recognizable pattern (p. 60). In patients with non-organic loss, the loss is often complete, affecting all modalities and in a distribution that does not conform to an anatomical sensory distribution. There are often inconsistencies on repeat testing. There is usually a discrepancy in the functional loss associated with the sensory loss, for example an arm apparently without joint position sense can still touch the nose with eyes shut or reliably touches the same spot just to one side of the nose.

Visual loss

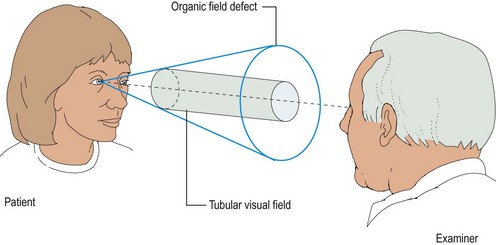

This can occur in a wide range of different patterns, and in each there is a range of differential diagnoses that need careful consideration. Signs that prove useful are the finding of a ‘tube’ field loss that does not broaden as it gets further from the eye (Fig. 2).