Chapter 82 Functional and Dissociative (Psychogenic) Neurological Symptoms

Terminology

Psychiatric Terminology

Conversion disorder (DSM-IV 300.11) is based on the Freudian idea that intolerable psychological conflict leads to the conversion of distress into physical symptoms. The current definition requires that the symptoms are “not feigned” and that psychological factors judged to be “associated with the symptom or deficit because conflicts or other stressors precede the initiation or exacerbation of the symptom or deficit” be present. In practice, these two criteria are so untestable, they are likely to be dropped from the DSM-5. The conversion hypothesis is now just one of many competing hypotheses trying to explain these symptoms (Stone et al., 2010a).

Conversion disorder (DSM-IV 300.11) is based on the Freudian idea that intolerable psychological conflict leads to the conversion of distress into physical symptoms. The current definition requires that the symptoms are “not feigned” and that psychological factors judged to be “associated with the symptom or deficit because conflicts or other stressors precede the initiation or exacerbation of the symptom or deficit” be present. In practice, these two criteria are so untestable, they are likely to be dropped from the DSM-5. The conversion hypothesis is now just one of many competing hypotheses trying to explain these symptoms (Stone et al., 2010a).

Dissociative seizure/motor disorder (conversion disorder) (ICD-10 F44.4-9) suggests dissociation as an important mechanism in symptom production. Dissociation encompasses a variety of symptoms in which there is a lack of integration or connection of normal conscious functions. The difficulty is that not all patients with functional symptoms describe dissociative symptoms (see History Taking, later).

Dissociative seizure/motor disorder (conversion disorder) (ICD-10 F44.4-9) suggests dissociation as an important mechanism in symptom production. Dissociation encompasses a variety of symptoms in which there is a lack of integration or connection of normal conscious functions. The difficulty is that not all patients with functional symptoms describe dissociative symptoms (see History Taking, later).

Somatization disorder (DSM-IV 300.81) is applied to a patient with a history of symptoms unexplained by disease, starting before the age of 30. The current definition requires at least 1 “conversion” symptom, 4 pain symptoms, 2 gastrointestinal symptoms (usually irritable bowel syndrome), and 1 sexual symptom (dyspareunia, dysmenorrhea, or hyperemesis gravidarum). This definition is also likely to change in the DSM-5.

Somatization disorder (DSM-IV 300.81) is applied to a patient with a history of symptoms unexplained by disease, starting before the age of 30. The current definition requires at least 1 “conversion” symptom, 4 pain symptoms, 2 gastrointestinal symptoms (usually irritable bowel syndrome), and 1 sexual symptom (dyspareunia, dysmenorrhea, or hyperemesis gravidarum). This definition is also likely to change in the DSM-5.

Hypochondriasis describes excessive and intrusive health anxiety about the possibility of serious disease which the patient has trouble controlling. Typically the patient seeks repeated medical reassurance, which only has a short-lived effect. Health anxiety is often present to varying degrees in patients with psychogenic/functional symptoms but may be completely absent.

Hypochondriasis describes excessive and intrusive health anxiety about the possibility of serious disease which the patient has trouble controlling. Typically the patient seeks repeated medical reassurance, which only has a short-lived effect. Health anxiety is often present to varying degrees in patients with psychogenic/functional symptoms but may be completely absent.

Factitious disorder (DSM-IV 300.19) describes symptoms that are consciously fabricated for the purpose of medical care or other nonfinancial gain.

Factitious disorder (DSM-IV 300.19) describes symptoms that are consciously fabricated for the purpose of medical care or other nonfinancial gain.

Munchausen syndrome describes someone with factitious disorder who wanders between hospitals, typically changing their name and story. There is a strong association with severe personality disorder.

Munchausen syndrome describes someone with factitious disorder who wanders between hospitals, typically changing their name and story. There is a strong association with severe personality disorder.

Malingering is not a psychiatric diagnosis but describes the deliberate fabrication of symptoms for material gain.

Malingering is not a psychiatric diagnosis but describes the deliberate fabrication of symptoms for material gain.

Other Terminology

Our preferred terms for motor/sensory symptoms and blackouts unexplained by disease are functional and dissociative because they describe a mechanism and not an etiology, they sidestep an illogical debate about whether symptoms are in the mind or the brain, and they can be used easily with patients. For simplicity, the term functional is used in this chapter, although psychogenic remains a popular term, especially among U.S. neurologists (Espay et al., 2009).

Psychogenic, psychosomatic, and somatization all describe an exclusively psychological etiology.

Psychogenic, psychosomatic, and somatization all describe an exclusively psychological etiology.

Functional describes in the broadest possible sense a problem due to a change in function (of the nervous system) rather than structure. This has the advantage of sidestepping the problems of etiology but can be criticized for being too broad a term.

Functional describes in the broadest possible sense a problem due to a change in function (of the nervous system) rather than structure. This has the advantage of sidestepping the problems of etiology but can be criticized for being too broad a term.

Nonorganic, nonepileptic describes what the problem is not, rather than what it is.

Nonorganic, nonepileptic describes what the problem is not, rather than what it is.

No diagnosis. Many neurologists, even when faced with clear evidence of a functional/psychogenic neurological problem, are in the habit of making no diagnosis at all and simply concluding that there is no evidence of neurological disease (Friedman and LaFrance, Jr., 2010).

No diagnosis. Many neurologists, even when faced with clear evidence of a functional/psychogenic neurological problem, are in the habit of making no diagnosis at all and simply concluding that there is no evidence of neurological disease (Friedman and LaFrance, Jr., 2010).

Medically unexplained superficially appears to be a neutral term but is often interpreted by patients and doctors as not knowing what the diagnosis is, rather than not knowing why they have the problem. Furthermore, many neurological diseases have uncertain etiology.

Medically unexplained superficially appears to be a neutral term but is often interpreted by patients and doctors as not knowing what the diagnosis is, rather than not knowing why they have the problem. Furthermore, many neurological diseases have uncertain etiology.

Hysteria, an ancient term originating from the idea of the “wandering womb” causing physical symptoms, is generally viewed a pejorative.

Hysteria, an ancient term originating from the idea of the “wandering womb” causing physical symptoms, is generally viewed a pejorative.

Epidemiology in Neurology and Other Medical Specialties

A number of studies of neurological practice have found that around one-third of neurological outpatients present with symptoms the neurologist does not think relate to neurological disease. In half of these (around one-sixth of all patients) the neurologist makes a primary “functional” or “psychogenic” diagnosis. The rest have some neurological disease but symptoms out of proportion to that disease (Stone et al., 2009). These figures mirror those in other medical specialties where functional symptoms comprise around a third to half of patients seeing a cardiologist, gastroenterologist, rheumatologist, and other specialty practices. Table 82.1 lists functional symptoms and syndromes according to specialty. Patients with functional neurological symptoms have much higher rates of these other non-neurological functional symptoms (Crimlisk et al., 1998).

Table 82.1 Functional Symptoms and Syndromes According to Medical Specialty

| Specialty | Symptoms |

|---|---|

| Gastroenterology | Irritable bowel syndrome |

| Respiratory | Chronic cough, brittle asthma (some) |

| Rheumatology | Fibromyalgia, chronic back pain (some) |

| Gynecology | Chronic pelvic pain, dysmenorrhea (some) |

| Allergy | Multiple chemical sensitivity syndrome |

| Cardiology | Atypical/noncardiac chest pain, palpitations (some) |

| Infectious diseases | (Postviral) chronic fatigue syndrome, chronic Lyme disease (where physician disagrees that there is ongoing infection) |

| Ear, nose, and throat | Globus sensation, functional dysphonia |

| Neurology | Nonepileptic attacks, functional weakness and sensory symptoms |

| Psychiatry | Depression, anxiety |

Studies of patients with functional neurological symptoms have shown that they report just as much physical disability and are more distressed than patients with neurological disease. Patients with these symptoms are more likely to be out of work because of ill health than the general population (Carson et al., 2010). Findings are similar in other specialties.

Clinical Assessment of Functional and Dissociative (Psychogenic) Symptoms

General Advice in History Taking

1. Start by making a list of all physical symptoms. Patients with functional symptoms typically have multiple physical symptoms. Making a list of them at the beginning avoids symptoms cropping up later, helps build rapport, and allows an early appreciation of the main difficulties. Do not, however, take detailed information about every symptom at this stage. Always ask about fatigue, pain, sleep disturbance, memory and concentration symptoms, and dizziness. It may seem counterintuitive to be seeking more symptoms in someone who is already polysymptomatic, but sometimes these symptoms, especially fatigue, are reluctantly volunteered even though they often cause the most limitation.

2. Dissociative symptoms. Dizziness, if present, may turn out to be dissociative in nature (e.g., feeling “spaced out,” “there but not there,” or “unreal”). Patients have trouble describing dissociation, partly because it is hard to describe but also because they fear the symptoms indicate “craziness.” Depersonalization describes feeling disconnected from your own body; derealization is a feeling of being disconnected from your surroundings.

3. Onset. The onset in patients with weakness and movement disorders is sudden in around half of patients. Physical injury, pain, or acute symptoms of dissociation or panic are common in this situation. More gradual-onset symptoms are often associated with fatigue.

4. What can the patient do? Patients with functional symptoms have a tendency to report what they can no longer do rather than what they can do. While it is helpful to hear about previous function, ask what they are able to do—do they enjoy it?

5. Look for other functional symptoms and syndromes (see Table 82.1). The more they have, the more likely it is that the presenting neurological complaint is functional. Patients can rotate between different specialists, with none appreciating their vulnerability to functional symptoms in general.

6. Ask the patient what they think is wrong and what should be done. If they or their family have been concerned or wondering about a specific neurological disease such as multiple sclerosis, Lyme disease, or “trapped nerves,” this information is important to tailoring an explanation for the diagnosis later on. Do they have health anxiety? Do they think they are irreversibly damaged? Efforts at rehabilitation may be futile unless beliefs about damage can be altered. In one prospective study of outpatients, beliefs about irreversibility predicted outcome more than age, physical disability, and distress (Sharpe et al., 2009). What happened with previous doctors and why have they come to see you? Some patients seek diagnosis and treatment, others are simply looking for a label for a problem they do not expect to resolve.

7. Avoid blunt questions about depression and anxiety. It is not necessary for the purposes of neurological diagnosis to make an accurate assessment of a patient’s psychological state on the first visit. The diagnosis of functional symptoms should be made on the basis of the physical symptoms. It often may be wise to leave questions about emotions for later; only a minority of patients with functional symptoms believe that stress or psychological factors have anything to do with their symptoms, in contrast to patients with disease who commonly attribute their symptoms to stress (Stone et al., 2010b). Patients with functional symptoms do have high rates of depression and anxiety but are often wary of questions about their emotions. They often feel that the doctor is angling to blame their physical symptoms on them personally. Blunt questions like, “Are you depressed or anxious?” may not therefore yield accurate answers. Instead try the following:

For depression, ask about activities they can do and whether they get enjoyment from them; if not, they may have anhedonia. If hospitalized, do they look forward to visits from friends and family? Look at the patient—are they miserable or avoiding eye contact? Or try framing questions around the physical symptoms: “Does your weakness get you down?” Depression is likely when there is persistent anhedonia or low mood most of the time, with four or more of the following: fatigue, sleep disturbance, suicidal ideation, poor memory or concentration, psychomotor retardation/agitation, or feelings of worthlessness/guilt and/or suicidal ideation.

For depression, ask about activities they can do and whether they get enjoyment from them; if not, they may have anhedonia. If hospitalized, do they look forward to visits from friends and family? Look at the patient—are they miserable or avoiding eye contact? Or try framing questions around the physical symptoms: “Does your weakness get you down?” Depression is likely when there is persistent anhedonia or low mood most of the time, with four or more of the following: fatigue, sleep disturbance, suicidal ideation, poor memory or concentration, psychomotor retardation/agitation, or feelings of worthlessness/guilt and/or suicidal ideation. For anxiety, look for three out of the following six symptoms: restlessness/on edge, insomnia, fatigue, irritability, poor concentration, and/or tense muscles combined with a history of worry that is persistent and hard to control. Worry will often be primarily focused on health.

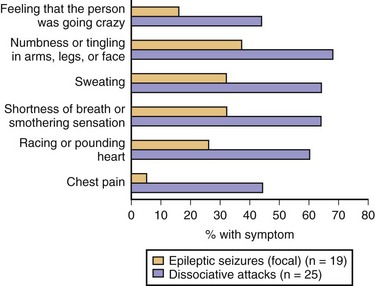

For anxiety, look for three out of the following six symptoms: restlessness/on edge, insomnia, fatigue, irritability, poor concentration, and/or tense muscles combined with a history of worry that is persistent and hard to control. Worry will often be primarily focused on health. For panic attacks, look for four of the following: palpitations, sweating, trembling/shaking, shortness of breath, choking sensation, chest pain/pressure, nausea/feeling of imminent diarrhea, dizziness, derealization/depersonalization, afraid of going crazy/losing control, afraid of dying, tingling, flushes/chills. Panic is a very common problem in patients with functional symptoms, especially nonepileptic attacks. Typically they are not reported as panic attacks at all, but rather attacks where the patient unexpectedly had multiple symptoms all at once. The emotional component of the panic attack is experienced but erroneously attributed by the patient as being an understandable fear about the physical “attack” that is occurring.

For panic attacks, look for four of the following: palpitations, sweating, trembling/shaking, shortness of breath, choking sensation, chest pain/pressure, nausea/feeling of imminent diarrhea, dizziness, derealization/depersonalization, afraid of going crazy/losing control, afraid of dying, tingling, flushes/chills. Panic is a very common problem in patients with functional symptoms, especially nonepileptic attacks. Typically they are not reported as panic attacks at all, but rather attacks where the patient unexpectedly had multiple symptoms all at once. The emotional component of the panic attack is experienced but erroneously attributed by the patient as being an understandable fear about the physical “attack” that is occurring.8. Do not always expect psychological comorbidity or life events. Depression and anxiety are common, but around one-third of patients will have neither. Likewise, although some patients have a history of a recent life event or stress, this is not always present. Sometimes the panic attack or physical injury that triggered the symptom is the most stressful life event, and the presence of the symptom then serves to perpetuate the anxiety. Avoiding a diagnosis of functional symptoms in someone just because they seem “normal” is as great an error as making the diagnosis simply because the patient has a lot of obvious psychological comorbidity.

General Advice in Specific Physical Diagnosis

The diagnosis of functional symptoms should always be made on the basis of either:

Clinical features typical of a functional/dissociative diagnosis (e.g., a typical thrashing dissociative [nonepileptic] attack with side-to-side head movements and eyes closed for 5 minutes).

Clinical features typical of a functional/dissociative diagnosis (e.g., a typical thrashing dissociative [nonepileptic] attack with side-to-side head movements and eyes closed for 5 minutes).

Physical signs demonstrating internal inconsistency (e.g., Hoover sign for functional weakness, entrainment in functional tremor—see later discussion).

Physical signs demonstrating internal inconsistency (e.g., Hoover sign for functional weakness, entrainment in functional tremor—see later discussion).

La belle indifference (smiling indifference to disability) has no diagnostic value, since it may be present in neurological disease (Stone et al., 2006). When it is present, it often reflects a conscious desire on the patient’s behalf to appear happy in a situation where they are aware they are under psychiatric “suspicion,” or alternatively may indicate factitious disorder.

Blackouts/Dissociative (Nonepileptic) Attacks

Dissociative (nonepileptic) attacks are the most common type of symptom unexplained by disease seen in neurological practice (Schacter and LaFrance, Jr., 2010). Studies have estimated that up to 1 in 7 patients in a “first fit” clinic, 50% of patients brought in by ambulance in apparent status epilepticus, and around 20% to 50% of patients admitted for videotelemetry have this diagnosis. Peak incidence is in the mid-20s; females predominate 3 : 1. Later-onset patients in their 40s and 50s have a 1 : 1 gender ratio and typically have health anxiety and a history of recent “organic” health problems (Duncan et al., 2006).

The diagnosis is usually made on the basis of the observable features of an attack, preferably recorded using video electroencephalography (EEG) (Table 82.2). No one feature should be used on its own to make a diagnosis, but some are more reliable than others (Avbersek and Sisodiya, 2010). Data on the reliability of these signs have largely been taken from studies of videotelemetry; these signs are less reliable when based on witness descriptions.

Table 82.2 Differentiating Dissociative (Nonepileptic) Attacks from Generalized Tonic-Clonic Epileptic Seizures

| Dissociative Attacks | Epileptic Seizures | |

|---|---|---|

| HELPFUL | ||

| Duration over 2 minutes* | Common | Rare |

| Fluctuating course* | Common | Rare |

| Eyes and mouth closed* | Common | Rare |

| Resisting eye opening | Common | Very rare |

| Side-to-side head or body movement* | Common | Rare |

| Opisthotonus, arc de cercle | Occasional | Very rare |

| Visible large bite mark on side of tongue/cheek/lip | Very rare | Occasional |

| Dislocated shoulder | Very rare | Occasional |

| Fast respiration during attack | Common | Ceases |

| Grunting/guttural ictal cry sound | Rare | Common |

| Weeping/upset after a seizure* | Occasional | Very rare‡ |

| Recall for period of unresponsiveness* | Common | Very rare |

| Thrashing, violent movements | Common | Rare |

| Postictal stertorous breathing* | Rare | Common |

| Pelvic thrusting*† | Occasional | Rare§ |

| Asynchronous movements*† | Common | Rare |

| Attacks in medical situations | Common | Rare |

| NOT SO HELPFUL | ||

| Stereotyped attacks | Common | Common |

| Attack arising from sleep | Occasional | Common |

| Aura | Common | Common |

| Incontinence of urine or feces* | Occasional | Common |

| Injury* | Common¶ | Common |

| Report of tongue biting* | Common | Common |

* Endorsed by a recent systematic review (Avbersek, A., Sisodiya, S., 2010. Does the primary literature provide support for clinical signs used to distinguish psychogenic nonepileptic seizures from epileptic seizures? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 81, 719-725.).

† These signs unhelpful in distinguishing nonepileptic attacks from frontal lobe seizures.

§ Frontal lobe epilepsy. Nonepileptic attacks do appear to arise from sleep, but video electroencephalogram (EEG) usually shows this not to be true sleep. Attacks arising from EEG-documented sleep are suggestive of epilepsy.

¶ Especially carpet burns and bruising.

Attention has shifted in recent years to diagnosis using subjective experience of the attack. Patients with dissociative attacks typically do not volunteer a prodrome. Indeed, studies analyzing dialogue between neurologists and patients have shown that the lack of any attempt to describe a prodrome may be of diagnostic value in itself, since patients with epilepsy usually do attempt to describe their prodrome when present, compared to patients with dissociative attacks who describe the disability associated with the attack (Reuber et al., 2009). However, if questioned, many patients with nonepileptic attacks will admit to a brief prodrome with features of panic (Goldstein and Mellers, 2006) (Fig. 82.1). If obtained, this is useful information that gives the clinician windows into both understanding the nature of the attacks (a mechanism related to panic attacks in which the patient dissociates) and possible treatment (teaching the patient distraction techniques to use during this warning phase to avert the attack and following treatment principles for panic disorder). As some patients recover, they may experience awareness during the attack itself.

Video EEG may be supplemented by an open suggestion protocol to help record an attack (Benbadis et al., 2000). Deceptive placebo induction with saline or a tuning fork is more controversial. Postictal prolactin measurement (to detect high prolactin after a generalized seizure) has fallen out of favor owing to problems with the reliability and timing of the test. Diagnostic pitfalls include coexistent epilepsy (present in 5%–20% of patients), frontal lobe seizures, sleep-related movement disorders, and paroxysmal movement disorders.

Weakness/Paralysis

Weakness as a functional symptom is more common in females and typically presents in the mid-thirties but like all functional symptoms can occur in children and the elderly. Estimates of incidence are around 5/100,000, comparable to multiple sclerosis. Comorbidity with other functional symptoms, especially fatigue and pain, is almost invariable. The most common presentation is unilateral weakness with no good evidence for left-sided or nondominant preponderance, followed by monoparesis and paraparesis. Complete paralysis is less common clinically (Stone et al., 2010b).

The onset is sudden in around 50% of patients. In the acute presentation, there are often symptoms of a panic attack, dissociative seizure, or an immediate trigger such as a physical injury, acute pain, migraine, a general anesthetic, or an episode of sleep paralysis (Stone et al., 2011). When the onset is more gradual, there is typically a history of fatigue, pain, or immobility on which the weakness becomes superimposed gradually over time. The weakness seen in complex regional pain syndrome type 1 (CRPS1) (Birklein et al., 2000) has the same clinical features as functional weakness.

Pattern of weakness. In functional weakness, the limb is usually globally weak or often demonstrates the inverse of pyramidal weakness, with the flexors weaker in the arms and the extensors weaker in the legs.

Pattern of weakness. In functional weakness, the limb is usually globally weak or often demonstrates the inverse of pyramidal weakness, with the flexors weaker in the arms and the extensors weaker in the legs.

Inconsistency during examination. This may be obvious—for example, a patient who can walk to the examination table but cannot raise the leg against gravity on examination. More commonly there is weakness of ankle movements, but the patient can stand on tiptoes or on their heels. Arm weakness may be incompatible with performance, such as removing shoes or carrying a bag.

Inconsistency during examination. This may be obvious—for example, a patient who can walk to the examination table but cannot raise the leg against gravity on examination. More commonly there is weakness of ankle movements, but the patient can stand on tiptoes or on their heels. Arm weakness may be incompatible with performance, such as removing shoes or carrying a bag.

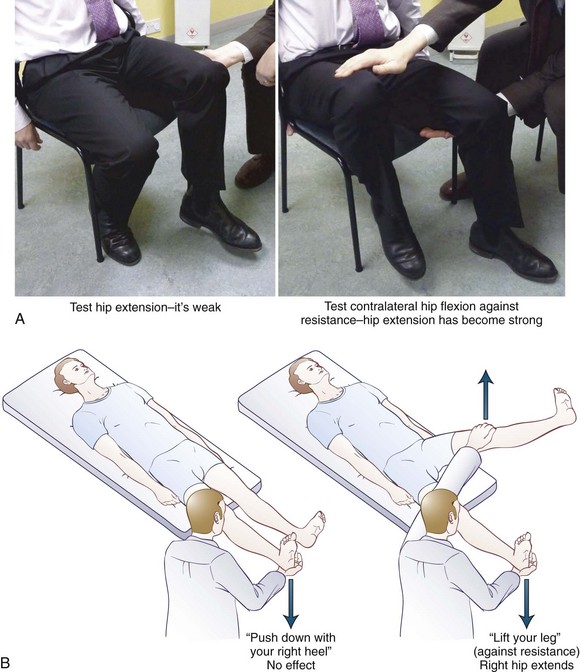

Hoover sign. Hip extension must be weak for this test to work. The presence of hip extension weakness itself in an ambulant patient is a positive sign of functional weakness. If hip extension returns to normal during contralateral hip flexion against resistance, this demonstrates structural integrity of the motor pathways (Fig. 82.2). The test is easiest to do with the patient in the sitting position. We find it useful to demonstrate this sign to the patient and relatives to indicate that the diagnosis is being made on the basis of positive criteria. This test may be false positive when there is cortical neglect.

Hoover sign. Hip extension must be weak for this test to work. The presence of hip extension weakness itself in an ambulant patient is a positive sign of functional weakness. If hip extension returns to normal during contralateral hip flexion against resistance, this demonstrates structural integrity of the motor pathways (Fig. 82.2). The test is easiest to do with the patient in the sitting position. We find it useful to demonstrate this sign to the patient and relatives to indicate that the diagnosis is being made on the basis of positive criteria. This test may be false positive when there is cortical neglect.

Hip abductor sign. A similar test involves demonstrating weakness of hip abduction which returns to normal with contralateral hip abduction against resistance.

Hip abductor sign. A similar test involves demonstrating weakness of hip abduction which returns to normal with contralateral hip abduction against resistance.

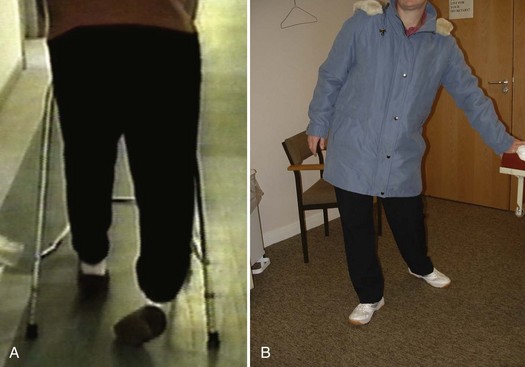

Dragging gait. If there is moderate or severe unilateral leg weakness, the patient may walk with a dragging gait in which the foot does not leave the ground. Often the hip is externally or internally rotated (Fig. 82.3).

Dragging gait. If there is moderate or severe unilateral leg weakness, the patient may walk with a dragging gait in which the foot does not leave the ground. Often the hip is externally or internally rotated (Fig. 82.3).

“Give-way” weakness. This is a pattern of weakness in which the patient transiently has normal power but then the limb gives way, sometimes just before it is touched. If the arm is very weak it may hover for a second before collapsing. Normal power can be produced by saying to the patient, “At the count of 3, push—1 … 2 … 3 … push.” This is a less reliable sign and occurs more commonly in painful limbs or occasionally in myasthenia gravis.

“Give-way” weakness. This is a pattern of weakness in which the patient transiently has normal power but then the limb gives way, sometimes just before it is touched. If the arm is very weak it may hover for a second before collapsing. Normal power can be produced by saying to the patient, “At the count of 3, push—1 … 2 … 3 … push.” This is a less reliable sign and occurs more commonly in painful limbs or occasionally in myasthenia gravis.

Facial weakness. Pseudoptosis is recognized in which the forehead appears weak, with a depressed eyebrow. In fact, the problem is overactivity of the orbicularis oculus muscle. A similar appearance of lower facial weakness due to overactivity of the platysma muscle can occur. These features can sometimes be enhanced on examination by sustained voluntary contraction of facial or periocular muscles.

Facial weakness. Pseudoptosis is recognized in which the forehead appears weak, with a depressed eyebrow. In fact, the problem is overactivity of the orbicularis oculus muscle. A similar appearance of lower facial weakness due to overactivity of the platysma muscle can occur. These features can sometimes be enhanced on examination by sustained voluntary contraction of facial or periocular muscles.

“Altered” reflexes. Occasionally, patients with functional weakness may have what appears to be ankle clonus, which on closer inspection has features of functional tremor. There may also appear to be reflex asymmetry if the patient is co-contracting agonist and antagonist muscles on one side of their body. Finally, in our experience it is not that unusual for the plantar response to be relatively mute on the affected side if there is marked sensory disturbance.

“Altered” reflexes. Occasionally, patients with functional weakness may have what appears to be ankle clonus, which on closer inspection has features of functional tremor. There may also appear to be reflex asymmetry if the patient is co-contracting agonist and antagonist muscles on one side of their body. Finally, in our experience it is not that unusual for the plantar response to be relatively mute on the affected side if there is marked sensory disturbance.

Movement Disorders

Functional movement disorders have been increasingly recognized by movement disorder specialists, especially over the last decade. In specialist clinics, these symptoms account for up to 10% of new referrals (Hallett et al., 2006). Like weakness, the onset of functional movement disorders is often sudden or may be accompanied by pain. The course may be unusual, with sudden remissions or relapses in different limbs. General clues to a functional movement disorder include improvement with distraction (many so-called organic movement disorders get worse during distraction) and worsening with attention. Many organic movement disorders, especially gait disorders, can look bizarre, but if a clinician is careful to only make the diagnosis on positive grounds, it should not be as intimidating a diagnosis as it first appears. Fahn and Williams proposed a classification of psychogenic movement disorders in which documented indicated resolution with placebo or psychotherapy, and clinically established indicated that there was clear positive evidence along with other functional/psychogenic signs (Fahn and Williams, 1988). In practice, most patients have a clinically established movement disorder. Caution is warranted insofar as organic movement disorders can also improve temporarily with placebo.

Tremor

Variable frequency, which may include starting and stopping of the tremor. This is more useful than variable amplitude, which can be found in organic tremor.

Variable frequency, which may include starting and stopping of the tremor. This is more useful than variable amplitude, which can be found in organic tremor.

Entrainment test, which is carried out by asking the patient to make a rhythmical tapping movement with their unaffected limb, preferably at around 3 Hz. It can be improved if the patient is externally cued by having to copy a similar movement in the examiner. If the tremor is functional, one of three things happens: (1) the patient is unable to copy the simple tapping movement and cannot explain why, (2) the tremor in the affected limb stops, or (3) the tremor in the affected hand entrains to the same rhythm as the examiner. False positives in this test appear to be rare. False negatives, on the other hand, are more common, particularly if the tremor is long-standing (and hence more automatic) or if the tremor relies on mechanics. For example, a heel tapping leg tremor in someone sitting with their foot plantarflexed on the ground is characteristic of a functional tremor (Hallett, 2010). Accelerometry, if available, can be helpful in recording the response to this test.

Entrainment test, which is carried out by asking the patient to make a rhythmical tapping movement with their unaffected limb, preferably at around 3 Hz. It can be improved if the patient is externally cued by having to copy a similar movement in the examiner. If the tremor is functional, one of three things happens: (1) the patient is unable to copy the simple tapping movement and cannot explain why, (2) the tremor in the affected limb stops, or (3) the tremor in the affected hand entrains to the same rhythm as the examiner. False positives in this test appear to be rare. False negatives, on the other hand, are more common, particularly if the tremor is long-standing (and hence more automatic) or if the tremor relies on mechanics. For example, a heel tapping leg tremor in someone sitting with their foot plantarflexed on the ground is characteristic of a functional tremor (Hallett, 2010). Accelerometry, if available, can be helpful in recording the response to this test.

Distractibility using mental tasks. Other forms of distraction such as being asked to calculate serial sevens can temporarily abolish tremor.

Distractibility using mental tasks. Other forms of distraction such as being asked to calculate serial sevens can temporarily abolish tremor.

Ballistic movements. Ask the patient to make sudden ballistic movements with their good hand by touching the rapidly moving finger of the examiner. Functional tremor will often stop briefly during the movement.

Ballistic movements. Ask the patient to make sudden ballistic movements with their good hand by touching the rapidly moving finger of the examiner. Functional tremor will often stop briefly during the movement.

Attempted immobilization. Attempting to immobilize the affected limb often makes a functional tremor worse. Likewise, loading the limb with weights tends to make the tremor worse, whereas organic tremor tends to improve with this maneuver.

Attempted immobilization. Attempting to immobilize the affected limb often makes a functional tremor worse. Likewise, loading the limb with weights tends to make the tremor worse, whereas organic tremor tends to improve with this maneuver.

Coactivation sign. Most functional tremor is similar to voluntary tremor. Sometimes the mechanism of the tremor is different and relates to coactivation of agonist and antagonist muscles (like shivering).

Coactivation sign. Most functional tremor is similar to voluntary tremor. Sometimes the mechanism of the tremor is different and relates to coactivation of agonist and antagonist muscles (like shivering).

Coherence analysis. If functional tremor is present in more than one limb, it usually has the same frequency. In contrast, organic tremor usually has slightly different frequencies in different body parts. Therefore, demonstrating coherence of the tremor between different body parts can provide supportive evidence of a functional tremor.

Coherence analysis. If functional tremor is present in more than one limb, it usually has the same frequency. In contrast, organic tremor usually has slightly different frequencies in different body parts. Therefore, demonstrating coherence of the tremor between different body parts can provide supportive evidence of a functional tremor.

Parkinsonism

The addition of slowness and postural instability to a patient with functional tremor can give the appearance of Parkinson disease, especially if the patient is also depressed and has diminished facial expression. The slowness is distractible and without the normal decrement seen in parkinsonism (Jankovic, J., 2011). There may be stiffness but with a quality of active resistance to it. Fluorodopa positron emission tomography (PET) scanning or dopamine transporter single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) scanning should be normal in functional movement disorder patients.

Myoclonus

Brief jerky movements may appear to be myoclonus. More commonly, patients have more complex hyperkinetic movements that are hard to accurately classify. Functional myoclonus may be stimulus sensitive, especially during deep tendon reflex testing, where myoclonus may occur even before the reflex hammer has made contact (Hallett, 2010). Functional/psychogenic myoclonus is often associated with a bereitschaft potential (BP) prior to the movement. This requires recording multiple events using EEG and back-averaging according to an electromyogram (EMG). The presence of a BP does not provide evidence of conscious intention to move but does indicate that the voluntary motor system is being utilized for the movement.

Dystonia

Dystonia has a troubled past relationship with so-called hysteria. In the heyday of psychoanalysis, cervical dystonia was interpreted as a “turning away of responsibility” and writers cramp as evidence of sexual conflict. Nonetheless, there is now a consensus that dystonic movements, especially fixed dystonia where the posture does not fluctuate, do occur as a functional/psychogenic phenomenon. The most common presentation is with a clenched fist, sometimes with wrist/elbow flexion or an inverted foot (Schrag et al., 2004) (Fig. 82.4). It is most frequently seen in association with limb pain in a situation where the diagnosis of CRPS1 may be made. As with functional weakness, there is no difference clinically between the abnormal movements seen in CRPS and those diagnosed as functional in the absence of pain. Fixed dystonia does occur without pain, commonly in a limb with functional weakness. Persistent fixed dystonia may be associated with contractures, which are best assessed under anesthetic.

Three neurophysiological studies have found it impossible to distinguish functional dystonia and organic dystonia on the basis of neurophysiological measures such as short and long intracortical inhibition, cortical silent period, and reciprocal inhibition in the forearm. One of these studies found that a measure of plasticity was increased in organic dystonia but was normal in functional dystonia (Hallett, 2010). It is perhaps with this symptom that traditional boundaries between psychogenic/organic and functional/structural are at their most blurred.

Gait Disorders

In studies of misdiagnosis, gait disorders figure disproportionately in cases where the initial diagnosis of a “nonorganic” problem turned out to be wrong. Nonetheless there are certain characteristic types of functional gait disorder (Lempert et al., 1991):

Dragging gait (as described in functional weakness).

Dragging gait (as described in functional weakness).

Tightrope walker’s gait with arms outstretched as if walking a tightrope, often with lurches to one side or the other but good recovery of balance.

Tightrope walker’s gait with arms outstretched as if walking a tightrope, often with lurches to one side or the other but good recovery of balance.

Astasia-abasia, which refers to normal limb power and sensation on the bed but inability to stand and walk. This can occur in organic truncal ataxia and sensory ataxia.

Astasia-abasia, which refers to normal limb power and sensation on the bed but inability to stand and walk. This can occur in organic truncal ataxia and sensory ataxia.

Crouching gait, which requires better strength and balance than a normal gait. Patients with this gait can be frightened of falling; this gait allows them to be closer to the ground.

Crouching gait, which requires better strength and balance than a normal gait. Patients with this gait can be frightened of falling; this gait allows them to be closer to the ground.

Knee-buckling gait, usually seen when the patient has unilateral functional weakness.

Knee-buckling gait, usually seen when the patient has unilateral functional weakness.

Sensory Disturbances

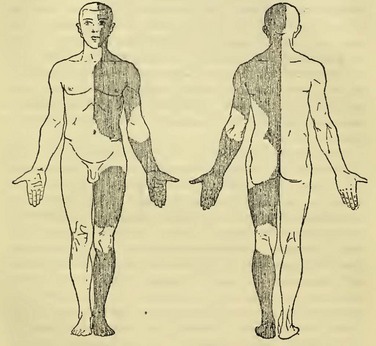

Hemisensory disturbance. Just as functional weakness is most commonly unilateral, the most common functional sensory symptom is the hemisensory syndrome in which the patient complains that one side of their body feels different from the other side (Fig. 82.5). They may complain that they feel “split down the middle” and also describe ipsilateral blurred vision or hearing problems. Functional sensory signs have been found in patients with chronic pain and complex regional pain (Rommel et al., 1999).

Hemisensory disturbance. Just as functional weakness is most commonly unilateral, the most common functional sensory symptom is the hemisensory syndrome in which the patient complains that one side of their body feels different from the other side (Fig. 82.5). They may complain that they feel “split down the middle” and also describe ipsilateral blurred vision or hearing problems. Functional sensory signs have been found in patients with chronic pain and complex regional pain (Rommel et al., 1999).

Sensation cut off at the groin or shoulder. This is usually associated with the patient’s dissociative report that the limb “feels as if its not there.”

Sensation cut off at the groin or shoulder. This is usually associated with the patient’s dissociative report that the limb “feels as if its not there.”

Fig. 82.5 A case of hemisensory disturbance depicted by Jean-Martin Charcot.

(From Charcot J.M., 1889. Clinical lectures on diseases of the nervous system. London, New Sydenham Society.)

Alteration of vibration sense across the forehead or sternum.

Alteration of vibration sense across the forehead or sternum.

Tests for complete sensory loss. Complete anesthesia is rare so that tests such as “Say yes when you feel it and no when you don’t” and “Close your eyes and touch your nose when I touch your hand” are rarely useful. The Bowlus maneuver involves having the patient interlock their fingers behind their back and asking them to state whether the right or left fingers are being touched.

Tests for complete sensory loss. Complete anesthesia is rare so that tests such as “Say yes when you feel it and no when you don’t” and “Close your eyes and touch your nose when I touch your hand” are rarely useful. The Bowlus maneuver involves having the patient interlock their fingers behind their back and asking them to state whether the right or left fingers are being touched.

Other sensory tests such as finding exact splitting of sensation at the midline or nondermatomal sensory loss are common but even less specific for functional sensory symptoms.

Other sensory tests such as finding exact splitting of sensation at the midline or nondermatomal sensory loss are common but even less specific for functional sensory symptoms.

Visual Symptoms

Functional visual symptoms and methods of detection include:

Intermittent blurred vision, often ipsilateral to functional weakness, and hemisensory disturbance, described elegantly as asthenopia in older texts. Patients may describe transiently screwing up their eyes to make it go away, which is suggestive of convergence spasm.

Intermittent blurred vision, often ipsilateral to functional weakness, and hemisensory disturbance, described elegantly as asthenopia in older texts. Patients may describe transiently screwing up their eyes to make it go away, which is suggestive of convergence spasm.

Double vision. Binocular diplopia is usually due to convergence spasm, asymmetrical overactivity of the normal convergence response. This can be demonstrated by testing convergence movements but holding the finger at a close distance for longer than usual. When persistent, convergence spasm can resemble a sixth nerve palsy. Monocular diplopia is usually functional but can be due to ocular pathology. Triplopia is surprisingly usually related to an organic eye movement abnormality but can be functional (Keane, 2006).

Double vision. Binocular diplopia is usually due to convergence spasm, asymmetrical overactivity of the normal convergence response. This can be demonstrated by testing convergence movements but holding the finger at a close distance for longer than usual. When persistent, convergence spasm can resemble a sixth nerve palsy. Monocular diplopia is usually functional but can be due to ocular pathology. Triplopia is surprisingly usually related to an organic eye movement abnormality but can be functional (Keane, 2006).

Total visual loss. Complete functional visual loss is normally relatively easy to diagnose at the bedside. Ask the patient to put their fingers together or sign their name (not a problem if organically blind). Extend a hand as if expecting a handshake, and watch them navigate around the room. Normal findings include pupillary response, menace reflex (sudden movements of the hand toward the eye), and optokinetic nystagmus with a rotating striped drum. There may be a convergence response to a mirror placed close in front of the face. Always consider the possibility of organic cortical blindness.

Total visual loss. Complete functional visual loss is normally relatively easy to diagnose at the bedside. Ask the patient to put their fingers together or sign their name (not a problem if organically blind). Extend a hand as if expecting a handshake, and watch them navigate around the room. Normal findings include pupillary response, menace reflex (sudden movements of the hand toward the eye), and optokinetic nystagmus with a rotating striped drum. There may be a convergence response to a mirror placed close in front of the face. Always consider the possibility of organic cortical blindness.

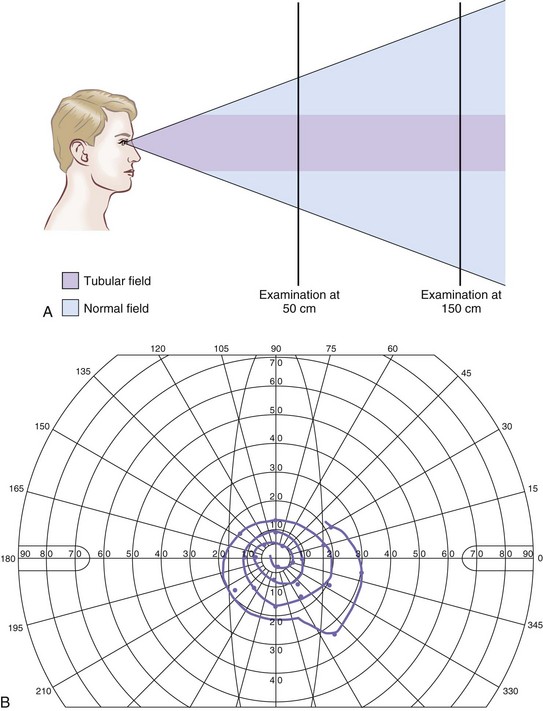

Monocular/partial visual loss. At the bedside, many patients with functional monocular symptoms have a tubular field defect (Fig. 82.6, A). Normally the visual field is conical, such that the visual field at 2 m is twice as large as at 1 m. Another common finding is spiral, star-shaped, or pinpoint visual fields on Goldmann perimetry (see Fig. 82.6, B). As the test proceeds, the patient tires and reports progressively constricted fields. A large variety of other tests exist to give an objective measure of acuity (Chen et al., 2007). For example, in monocular visual problems, the “fogging test” involves gradually worsening acuity in the good eye until the point when any acuity better than 6/60 must be coming from the affected eye. The stereoscopic test gives an estimate of acuity based on the perception of varying stereoscopic images.

Monocular/partial visual loss. At the bedside, many patients with functional monocular symptoms have a tubular field defect (Fig. 82.6, A). Normally the visual field is conical, such that the visual field at 2 m is twice as large as at 1 m. Another common finding is spiral, star-shaped, or pinpoint visual fields on Goldmann perimetry (see Fig. 82.6, B). As the test proceeds, the patient tires and reports progressively constricted fields. A large variety of other tests exist to give an objective measure of acuity (Chen et al., 2007). For example, in monocular visual problems, the “fogging test” involves gradually worsening acuity in the good eye until the point when any acuity better than 6/60 must be coming from the affected eye. The stereoscopic test gives an estimate of acuity based on the perception of varying stereoscopic images.

Hemifield loss. When this is functional, the patient will report binocular hemianopic fields, with monocular hemianopia on the side of the hemifield loss and normal monocular vision in the other eye.

Hemifield loss. When this is functional, the patient will report binocular hemianopic fields, with monocular hemianopia on the side of the hemifield loss and normal monocular vision in the other eye.

Nystagmus can sometimes be seen as a voluntary/functional phenomenon or in patients who spend a lot of time in the dark or wearing dark glasses.

Nystagmus can sometimes be seen as a voluntary/functional phenomenon or in patients who spend a lot of time in the dark or wearing dark glasses.

Speech and Swallowing Symptoms

Speech and swallowing symptoms commonly encountered in neurological practice are:

Articulation. Functional dysarthria usually takes the form of intermittent slurred speech or stuttering speech with difficulty starting words. Speech may be slow and with hesitations noticeably occurring in the middle of sentences when it is harder to interrupt. In this context, speech may become telegrammatic, missing the prepositions and conjunctions of normal speech. Just as functional weakness is at its worst when directly tested, functional speech problems are worst when having to repeat words or phrases to command and, like developmental stuttering, may resolve when the patient is singing or speaking about something that makes them feel emotional or angry. Complete mutism still occurs; we have seen a man who used a computer to speak for 4 years before making a good recovery.

Articulation. Functional dysarthria usually takes the form of intermittent slurred speech or stuttering speech with difficulty starting words. Speech may be slow and with hesitations noticeably occurring in the middle of sentences when it is harder to interrupt. In this context, speech may become telegrammatic, missing the prepositions and conjunctions of normal speech. Just as functional weakness is at its worst when directly tested, functional speech problems are worst when having to repeat words or phrases to command and, like developmental stuttering, may resolve when the patient is singing or speaking about something that makes them feel emotional or angry. Complete mutism still occurs; we have seen a man who used a computer to speak for 4 years before making a good recovery.

Dysphonia. Functional dysphonia is a common presenting symptom to otolaryngologists but may be seen by neurologists in combination with other functional symptoms. Speech is usually whispering in nature and may follow a genuine or perceived episode of laryngitis. At least six randomized controlled trials in this area have suggested benefit of voice therapy (Ruotsalainen et al., 2007).

Dysphonia. Functional dysphonia is a common presenting symptom to otolaryngologists but may be seen by neurologists in combination with other functional symptoms. Speech is usually whispering in nature and may follow a genuine or perceived episode of laryngitis. At least six randomized controlled trials in this area have suggested benefit of voice therapy (Ruotsalainen et al., 2007).

Globus pharyngis, which describes the symptom of “something sticking” in the throat, even when the patient is not swallowing anything. There is controversy regarding how often this symptom can be explained by gastroesophageal reflux disease and appropriate levels of investigation. Attributed by the Egyptians to a wandering womb (i.e., globus hystericus), if globus sensation is indeed due to reflux, it is striking how common this most ancient of functional symptoms is in patients with motor and sensory functional neurological symptoms.

Globus pharyngis, which describes the symptom of “something sticking” in the throat, even when the patient is not swallowing anything. There is controversy regarding how often this symptom can be explained by gastroesophageal reflux disease and appropriate levels of investigation. Attributed by the Egyptians to a wandering womb (i.e., globus hystericus), if globus sensation is indeed due to reflux, it is striking how common this most ancient of functional symptoms is in patients with motor and sensory functional neurological symptoms.

Memory and Cognitive Symptoms

“Normal” absentmindedness and functional memory symptoms. In someone who is usually not absentminded, forgetting why they went upstairs, losing their keys, or losing track of conversation may be interpreted as abnormal. Anxiety about the cause and attention paid to the symptom can amplify the problem and lead to neurological referral. A subgroup of patients in any memory clinic present without obvious anxiety, depression, or stress apart from anxiety about their memory symptoms (Schmidtke et al., 2008). In addition to escalating absentmindedness as described, the patient with functional memory symptoms usually reports variability in their memory problems and episodes when they forgot familiar information such as their own address and then remembered it again.

“Normal” absentmindedness and functional memory symptoms. In someone who is usually not absentminded, forgetting why they went upstairs, losing their keys, or losing track of conversation may be interpreted as abnormal. Anxiety about the cause and attention paid to the symptom can amplify the problem and lead to neurological referral. A subgroup of patients in any memory clinic present without obvious anxiety, depression, or stress apart from anxiety about their memory symptoms (Schmidtke et al., 2008). In addition to escalating absentmindedness as described, the patient with functional memory symptoms usually reports variability in their memory problems and episodes when they forgot familiar information such as their own address and then remembered it again.

Word-finding difficulty is a common symptom among patients with other functional neurological symptoms. They may also report mixing words up or neologisms, but true dysphasia is rare.

Word-finding difficulty is a common symptom among patients with other functional neurological symptoms. They may also report mixing words up or neologisms, but true dysphasia is rare.

Poor concentration as part of a psychological disorder. Attention and concentration may be noticeably impaired in anxiety and depression. In severe depression, the presentation may be that of a pseudodementia. Routine neuropsychological tests may give spuriously low values. Attempting to control for this with the use of self-reported anxiety and depression scales is unreliable in the authors’ experience.

Poor concentration as part of a psychological disorder. Attention and concentration may be noticeably impaired in anxiety and depression. In severe depression, the presentation may be that of a pseudodementia. Routine neuropsychological tests may give spuriously low values. Attempting to control for this with the use of self-reported anxiety and depression scales is unreliable in the authors’ experience.

Pure retrograde functional/psychogenic amnesia. This memory syndrome, common to fiction, also happens occasionally in real life. It presents with normal anterograde amnesia but with a large chunk of absent memory prior to a certain point. When not associated with obvious gain (e.g., a criminal who cannot remember the crime), it can occur in response to stress, perhaps as a self-deceptive phenomenon. The authors have seen several patients with this syndrome who wished to be at a previous time in their life, and their “amnesia” was best seen as compatible with that wish. Neurologists may be asked to see patients in fugue states who characteristically have moved from where they normally live and then cannot remember who they are or where they live.

Pure retrograde functional/psychogenic amnesia. This memory syndrome, common to fiction, also happens occasionally in real life. It presents with normal anterograde amnesia but with a large chunk of absent memory prior to a certain point. When not associated with obvious gain (e.g., a criminal who cannot remember the crime), it can occur in response to stress, perhaps as a self-deceptive phenomenon. The authors have seen several patients with this syndrome who wished to be at a previous time in their life, and their “amnesia” was best seen as compatible with that wish. Neurologists may be asked to see patients in fugue states who characteristically have moved from where they normally live and then cannot remember who they are or where they live.

In the assessment of patients with functional cognitive symptoms, approximate answers to questions (e.g., “How many legs has a horse got?” Answer: “3.”) are classically described. This has been called Ganser syndrome after the 19th century German psychiatrist who first reported it. In our experience, this is rare and is a marker of factitious symptoms. More common is the early loss of relatively “protected” knowledge such as the names of spouses or children, discrepancies between real-life function and test results, or discrepancies between results on cognitive tests that localize to the same anatomical region (e.g., memory). In such situations, cognitive “effort tests” may be useful. These are very simple tests that even patients with severe dementia or head injury should be able to perform well. For example, the coin-in-the-hand test involves 10 trials of showing a patient which hand a coin is held in, asking them to close their eyes for 10 seconds and then choose the hand with the coin (Kapur, 1994). A score at chance indicates poor effort. A score below chance is sometimes used as evidence of factitious disorder/malingering, although in reality it cannot distinguish between conscious or unconscious deception.

Overlap with Pain and Fatigue

Pain

We have discussed the similarity of functional motor and sensory symptoms seen in CRPS1 to those seen in patients without limb pain. The neurologist may also have to assess back pain in someone with functional symptoms. Certain signs, including some described by Gordon Waddell, do provide useful information (Waddell, 2004):

Straight leg raising while lying and sitting. If a patient can sit comfortably on an examination table with their legs stretched out at 90 degrees to their body, any pain induced by straight leg raising in the supine position cannot be due to true sciatic nerve pain.

Straight leg raising while lying and sitting. If a patient can sit comfortably on an examination table with their legs stretched out at 90 degrees to their body, any pain induced by straight leg raising in the supine position cannot be due to true sciatic nerve pain.

Simulated rotation. Ask the patient to stand with their feet flat on the floor and rotate the trunk with the arms stabilized at the sides. This movement occurs at the knees and not the back and should not cause significant back pain.

Simulated rotation. Ask the patient to stand with their feet flat on the floor and rotate the trunk with the arms stabilized at the sides. This movement occurs at the knees and not the back and should not cause significant back pain.

Localized tenderness. Some patients with back pain are exquisitely tender to superficial palpation.

Localized tenderness. Some patients with back pain are exquisitely tender to superficial palpation.

Axial loading. Pressure on the head should not cause significant back pain.

Axial loading. Pressure on the head should not cause significant back pain.

Fatigue

Fatigue may turn out, for all of the patient’s more obvious symptoms, to be their most limiting symptom. Chronic persistent fatigue in the absence of a disease cause has been labeled, defined, and conceived of in many ways—for example, chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS), neurasthenia, and myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME), some of which (ME) are based on the belief that the symptoms are due to an underlying neurological disease process yet to be fully elucidated. The fact that ME is listed as a neurological disorder and neurasthenia as a psychiatric disorder in the current ICD-10 classification indicates the nature of the controversy. One of the simpler definitions of CFS is persistent fatigue lasting longer than 6 months with no other neurological symptoms and not due to another cause. The relevance of this discussion is that there have been many randomized trials for CFS (Price et al., 2008) which potentially help to inform treatment for patients with functional neurological symptoms (where the evidence is more limited).

Feigning and Malingering

The issue of feigning remains topical in this area, firstly because these are symptoms without verifiable disease, and secondly—unlike, for example, irritable bowel syndrome—they are symptoms that relate to the voluntary nervous system (Kanaan et al., 2009). Distinguishing symptoms that are under conscious intentional voluntary control from those that are not is difficult because: (1) the positive signs used to make a diagnosis of functional symptoms would be the same if someone was feigning, (2) doctors are not trained to detect deception, and (3) some patients may be in a state of self-deception.

Although clinicians estimate feigning to account for around 5% of patients with functional symptoms, it is impossible for anyone to truly know. Most neurologists will come across patients in their career who have hoodwinked them or they may boast about those they caught out. It may be tempting to start believing that most patients are feigning. Several arguments stand in the way of this hypothesis: (1) the homogeneity of patient experiences as described in clinic, both of their symptoms and their general bewilderment; (2) follow-up studies showing symptom persistence over decades; (3) the high frequency of nonepileptic attacks during video EEG even when patients have been told this is the suspected diagnosis; (4) the persistence of positive signs such as the Hoover sign even when the patient has been shown how it operates; (5) evidence of shoe wear in patients with functional gait disorders and contractures in patients with fixed dystonia; (6) similar prevalence figures between industrialized nations with welfare benefit systems and nonindustrialized countries without (Simon et al., 1996); and (7) historical consistency in clinical presentation over centuries (Stone et al., 2008).

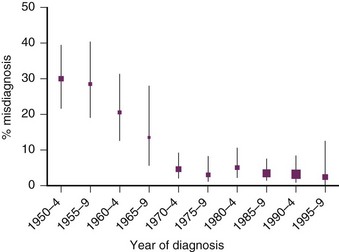

Misdiagnosis

While neurologists tend to worry about feigning, doctors other than neurologists, especially psychiatrists, tend to be preoccupied by the opposite concern of misdiagnosis. Studies in the 1950s and 1960s suggested high rates of the misdiagnosis of hysteria of up to 60%. Our systematic review of 27 studies included 1466 patients with a mean follow-up of 5 years and found a frequency of misdiagnosis of around 4% since 1970, before the advent of CT scans and videotelemetry (Stone et al., 2005). This is a frequency of misdiagnosis comparable to other neurological and psychiatric disorders. A recent study of 1144 patients in Scotland found an even lower misdiagnosis rate at 18 months of only 4 patients (Stone et al., 2009). This is not a reason for complacency, however, and we would recommend that neurologists continue to be responsible for these diagnoses. For neurologists, relying on obvious psychiatric comorbidity or making a diagnosis using gait disorder are common pitfalls.

Prognosis

Long-term follow-up studies have suggested that functional neurological symptoms persist in the majority and improve in a third (Crimlisk et al., 1998; Jankovic et al., 2006; McKenzie et al., 2010; Stone et al., 2003). As expected, sensory symptoms have a better prognosis than weakness, which in turn has a better outcome than fixed dystonia (Ibrahim et al., 2009).

Good prognostic factors for functional neurological symptoms are a willingness to accept the potential reversibility of the symptoms (Sharpe et al., 2009), an acceptance that psychological factors may play a part in symptom formation, a good interaction with the doctor, short duration of symptoms, lack of other physical symptoms, the presence of concurrent anxiety and depression (which can change), and removal of stress (Jankovic et al., 2006) or change in marital status (either divorce or marriage) (Crimlisk et al., 1998).

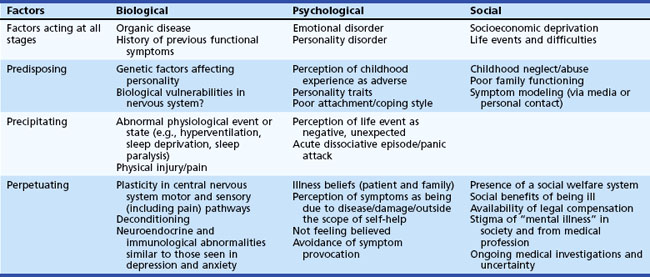

Etiology and Mechanism

The etiology of functional symptoms is multifactorial and varies hugely between patients. Although one can individually formulate an etiology for patients based on the factors shown in Table 82.3, this model is likely to be incomplete. If there is one rule here, it is avoid generalizing. The notion that all patients with functional symptoms have been abused or suffered some sort of trauma is not supported by the evidence. Likewise, although many patients with functional symptoms believe that stress is not relevant to their symptoms, between 25% and 50% do think it is relevant (Sharpe et al., 2009; Stone et al., 2010b). Having a neurological disease is an important and powerful risk factor for functional symptoms. Understanding prior vulnerabilities may help fill in general understanding about the problem, but it is really the perpetuating factors in Table 82.3 that are the most important target for treatment.

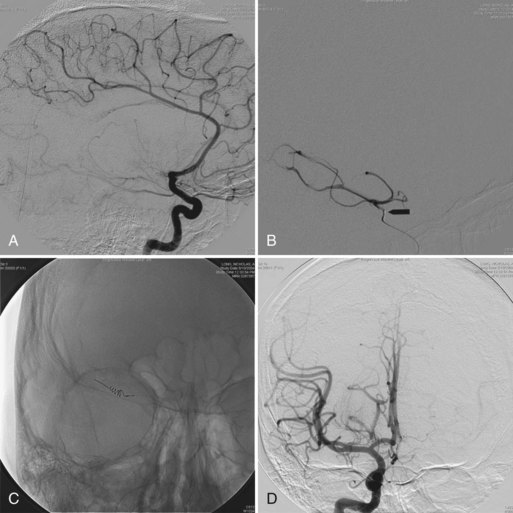

The neural mechanisms of functional neurological symptoms are not yet well understood, but functional imaging studies of functional motor symptoms combined with other neurophysiological techniques are adding to our understanding. A functional imaging study of unilateral weakness and sensory disturbance in four patients whose symptoms subsequently improved showed dose-responsive hypoactivation in contralateral thalamic and basal ganglia areas (Vuilleumier et al., 2001) (Fig. 82.7). Other studies are beginning to converge on a hypothesis that preemptor areas are overactive and not properly integrating with feed-forward areas in the brain, such as the parietal lobe, that may be responsible for the sense of agency of movement. This might help explain the apparent voluntariness of functional motor symptoms in the absence of a sense of intention on the part of the patient (Hallett, 2010). Another study found neural differences in patients feigning weakness compared to patients with actual functional weakness (Cojan et al., 2009). Neuroimaging and advances in neuroscience do hold out a promise of understanding symptoms in parallel neurological and psychiatric ways, with the hope of potentially being able to abandon the artificial distinction between the two.

Investigations

Investigations will usually be necessary, partly because the presence of a functional symptom does not exclude a comorbid underlying neurological disease, but it is worth considering how to perform them in the patient’s best interest if results are likely to be normal. If there is any delay in tests, patients can benefit from being told the likely diagnosis and that clinical investigations will probably be normal or show only incidental or age-related findings (Petrie et al., 2007). It is especially worth anticipating the 15% risk of nondiagnostic high-signal lesions on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and other “incidentalomas” (Morris et al., 2009) and the presence of age-related degenerative change on spinal MRI. If this must be done, an analogy with gray hair may be useful. Try to do all the necessary tests at the same time and not sequentially, which tends to prolong the agony of “diagnostic limbo.” Even if there are abnormalities on a scan, they cannot explain most of the positive signs described in this chapter.

Explanation

The diagnosis of a functional disorder is made on the basis of positive neurological features on assessment combined with a knowledge of the range of presentations of neurological disease, and not on the basis of psychiatric symptomatology—even though the latter may be relevant to etiology and treatment. Neurologists are therefore in a good position to explain the diagnosis of functional symptoms. A really successful explanation can alter outcome dramatically, even with long-standing symptoms. Most authors agree that a good explanation is a prerequisite to successful treatment with physiotherapy or psychological therapy, and there is some evidence that it does affect outcome (Carton et al., 2003; Jankovic et al., 2006). How the diagnosis is explained to the patient will depend on the clinician’s own views of why and how the symptoms are present; no method is suitable for all patients. Table 82.4 lists a series of components of explanation that we believe provide a constructive basis for further treatment.

Table 82.4 Ingredients of a Successful Explanation for Functional Symptoms

| Ingredient | Example |

|---|---|

| Explain what they do have | “You have functional weakness” “You have dissociative attacks” |

| Emphasize the mechanism of the symptoms rather than the cause | Weakness: “Your nervous system is not damaged, but it is not functioning properly” Attacks: “You are going into a trancelike state, a bit like someone being hypnotized” |

| Explain how you made the diagnosis | Show the patient their Hoover sign, tremor entrainment, or dissociative attack video, explaining why it is typical of the diagnosis you are making |

| Explain what they don’t have | “You do not have multiple sclerosis (epilepsy, etc.)” |

| Indicate that you believe them | “I do not think you are imagining/making up your symptoms/going crazy” |

| Emphasize that it is common | “I see lots of patients with similar symptoms” |

| Emphasize reversibility | “Because there is no damage, you have the potential to get better” |

| Emphasize that self-help is a key part of getting better | “This is not your fault, but there are things you can do to help it get better” |

| Metaphors may be useful | “The hardware is alright, but there’s a software problem” “It’s like a car/piano that’s out of tune” |

| Introduce the role of depression/anxiety | “If you have been feeling low/worried, that will tend to make the symptoms even worse” (often easier to achieve on a second visit) |

| Use written information | Send the patient their clinic letter; give them a website address (e.g., www.neurosymptoms.org, www.nonepilepticattacks.info) |

| Stop the antiepileptic drug in dissociative seizures | If you have diagnosed dissociative attacks and not epilepsy, stop the anticonvulsant; leaving the patient on the drug will hamper recovery |

| Suggest antidepressants when appropriate | “So-called antidepressants often help these symptoms even in patients who are not feeling depressed; they are not addictive” |

| Make the psychiatric referral when appropriate | “I don’t think you’re mentally ill, but Dr X has a lot of experience and interest in helping people like you to manage and overcome these kinds of symptoms. Are you willing to overcome any misgivings about his/her specialty to try to get better?” |

| Involve the family/friends | Explain it all to them as well |

The issue of whether one tells the patient they have psychogenic symptoms, conversion disorder, functional symptoms, or dissociative symptoms—terminology discussed at the beginning of this chapter—is only one of these components and is not as important as the totality of the explanation. A psychological explanation has the advantage of being clear-cut, compatible with psychiatric referral, and consistent with psychiatric terminology. Unfortunately, words such as psychogenic are commonly interpreted by a patient as meaning “crazy” or “making symptoms up,” so even if psychogenic is a given neurologist’s preferred term for theoretical reasons, it is important to consider whether the patient is translating the words into meanings never intended. A further disadvantage is that such terms are based on only one aspect of evidence concerning etiology. Finally, studies in primary care attempting to help patients reattribute their medically unexplained symptoms psychologically have not been successful. Functional is a more acceptable term (Stone et al., 2002), which along with dissociative describes a mechanism and leaves the etiology more open. These terms have the advantage of allowing a more integrated description involving biological, psychological, and social factors as stressors on neural function and allow treatment aimed at restoring nervous system function. The common criticism is that they are too broad and open to confusion. One option is to use a functional explanation by default and introduce discussion of psychological factors later if relevant or necessary. Even an unspoken suspicion that most patients with functional symptoms are feigning will likely be picked up on, regardless of what is said out loud.

There are many barriers to a successful explanation other than the words used. Patients with functional symptoms have often gone through a phase themselves of wondering, “Is it me?” because of the variability of the symptoms but, in contrast, also experience feelings of being out of control. They can therefore be particularly sensitive to a diagnosis that suggests that they are doing it on purpose or in control. Even when they are comfortable with the diagnosis of functional symptoms, this is a hard thing to explain to friends, family, and employers. Neurologists for their part are often unsure what to think about this area of their practice and may prefer to dodge the whole issue by explaining that there is no neurological disease. Patient frustration is the inevitable upshot; they want to know what is wrong with them, so more and more, they turn to the Internet (see self-help websites under When Nothing Helps, later).

Treatment

Psychological Treatment

Since up to one-third of all neurology outpatients have functional symptoms to some degree, it is unlikely they could all have specialist psychological treatment, nor do they all need it. Patients with mild symptoms may just need to be steered in the right direction, given sensible information, and they will do the rest themselves. Patients who are struggling with disabling symptoms are likely to benefit from further treatment. Recent randomized controlled trials have shown benefit of a cognitive behavioral treatment (CBT) over a 6-month period in nonepileptic attacks (Goldstein et al., 2010), a wider range of functional (psychogenic) symptoms (Sharpe et al., 2011), and in somatization disorder (Allen et al., 2006). Other uncontrolled studies have shown similar treatment effects for CBT in dissociative (nonepileptic) attacks (LaFrance, Jr. et al., 2009) and for more broad-based psychotherapy in a range of functional neurological symptoms (Reuber et al., 2007). But what does (and can) a psychiatrist/psychologist actually do with patients with functional symptoms?

Further explanation. A psychiatrist or psychologist must be familiar with the area and able to give the same kind of explanation the patient has received from the neurologist. This in itself may take some time.

Further explanation. A psychiatrist or psychologist must be familiar with the area and able to give the same kind of explanation the patient has received from the neurologist. This in itself may take some time.

Detection and treatment of comorbid psychiatric problems such as anxiety, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, or obsessive compulsive disorder.

Detection and treatment of comorbid psychiatric problems such as anxiety, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, or obsessive compulsive disorder.

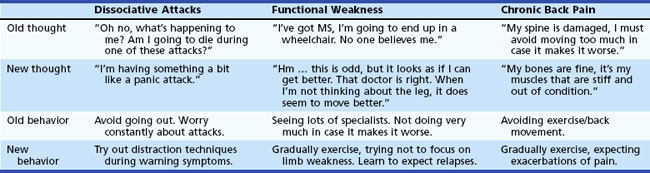

Cognitive behavioral treatment. This involves developing the patient’s diagnosis to change how they think about their symptoms and behave as a consequence of them (Table 82.5). It is an approach based in learning theory and aims to provide a detailed examination of the interactions between physical symptoms, thoughts, behavior, and mood. It applies a model that patients will gain immediate reward for their actions that influence future behavior; a patient with back pain may rest at the first signs of exacerbation, removing the pain in the short term but leading to long-term poorer function. Illness and other beliefs will also feature; the patient may believe that acute exacerbations of their back pain is a sign of new damage and thus strive to avoid this and become fearful of it. This can in turn result in increased muscle tension and poor posture, making the actual occurrence more likely. Such vicious circles are postulated as contributing to the genesis of functional symptoms, and the therapy aims to unpick them.

Cognitive behavioral treatment. This involves developing the patient’s diagnosis to change how they think about their symptoms and behave as a consequence of them (Table 82.5). It is an approach based in learning theory and aims to provide a detailed examination of the interactions between physical symptoms, thoughts, behavior, and mood. It applies a model that patients will gain immediate reward for their actions that influence future behavior; a patient with back pain may rest at the first signs of exacerbation, removing the pain in the short term but leading to long-term poorer function. Illness and other beliefs will also feature; the patient may believe that acute exacerbations of their back pain is a sign of new damage and thus strive to avoid this and become fearful of it. This can in turn result in increased muscle tension and poor posture, making the actual occurrence more likely. Such vicious circles are postulated as contributing to the genesis of functional symptoms, and the therapy aims to unpick them.