Chapter 2 Fractures: General Management

It is generally accepted that the majority of common fractures can be well managed by the general physician. These injuries are usually easily recognized both clinically and roentgenographically (Fig. 2-1). A satisfactory end result in their treatment will depend not only on the care of the fracture but also on restoration of the function of the injured extremity. These goals are reached by appreciating both the bony and soft tissue structures involved.

Terminology

Fracture: a break in the continuity of a bone

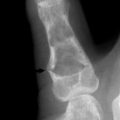

Fig. 2-2 Midshaft fractures of the humerus. A, Comminuted. B, Transverse,undisplaced. C, Oblique, undisplaced. D, Spiral. E, Segmental.

Alignment: rotational or angular position

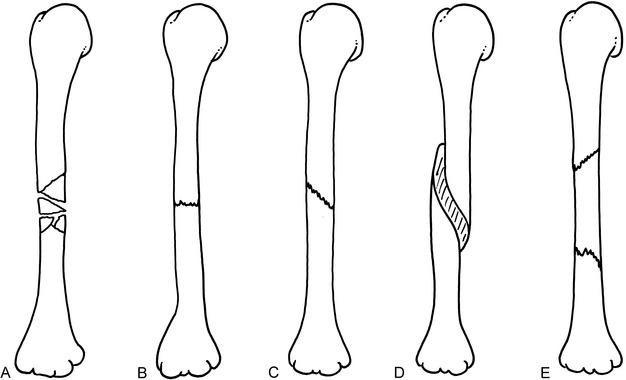

Apposition: amount of end-to-end contact of the fracture (Fig. 2-3)

Fig. 2-3 Apposition and alignment of midshaft fractures of the humerus, anteroposterior (AP) view. A, Perfect end-to-end apposition, perfect alignment. B, Fifty percent end-to-end apposition, perfect alignment. C, Side-to-side (bayonet) apposition, slight shortening, perfect alignment. D, No apposition, approximately 30-degree angulation.

Delayed union: fracture healing that is slower than normal

Dislocation (luxation): disruption in the continuity of a joint

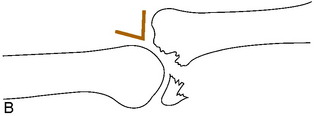

Fracture-dislocation: dislocation that occurs in conjunction with a fracture of the joint. If incomplete, it is called a fracture-subluxation (Fig. 2-4)

Malunion: healing in an unsatisfactory position

Nonunion: failure of bony healing

Pseudarthrosis: failure of bone healing that produces a “false joint” consisting of soft tissue

Subluxation: partial disruption in the continuity of a joint (an incomplete dislocation)

NOTE: Fractures do not dislocate, they displace (shorten, angulate, etc.). They are thus described according to the type, place in the bone, amount of displacement, and angulation (Fig. 2-5). Rotation (torsion) is often difficult to assess roentgenographically but relatively easy to assess clinically. Rotation is usually described in reference to the distal fragment, as is angulation.

General Considerations

INITIAL CARE

A variety of splinting devices are available that make transfer of the patient more comfortable (Fig. 2-6). Their use should be only temporary, however, until the diagnosis is confirmed roentgenographically. These splints should not be kept on more than a few hours, and certainly not overnight. They are very uncomfortable and are not meant for extended use. They fit poorly and do not allow for proper care of the soft tissue and control of swelling.

If definitive treatment of the fracture is to be delayed, a bulky, well-padded soft dressing supplemented with plaster splints, sometimes called the “Robert Jones” dressing, should be applied (Fig. 2-7). This dressing is made by first applying several layers of cast padding or cotton roll circumferentially to the extremity. Plaster splints may then be added, and the entire dressing is secured with gauze or elastic bandage. Precut padded plaster splints should not be used alone without first dressing the limb circumferentially in several layers of cast padding. Remember: the treatment of the soft tissue is as important as the protection of the fracture.

Fig. 2-7 A well-padded bulky dressing reinforced with plaster splints should be applied as soon as possible. Start with many layers of cast padding, because this dressing is temporary and is designed to control swelling and maintain fracture position. After padding is applied, plaster or fiberglass splints are added, and the splints are secured with an elastic bandage or roller gauze. An elastic bandage alone should never be used. It does not immobilize nor “reduce” swelling. It may, in fact, do more harm by further compressing the already compromised lymphatic and venous drainage systems. Short arm splints should be well padded around the wrist. Otherwise, the wrist and hand may “hang” over the edge of the plaster and pain may result.

The extremity is then elevated above the level of the heart, and ice is applied to control swelling. The neurologic and circulatory status of the extremity distal to the injury should always be checked and recorded (Table 2-1). A complete neurologic examination is usually unnecessary. If the patient can extend the thumb and flex and spread the fingers, the major nerves (radial, median, and ulnar) of the upper extremity are functioning; if the patient can flex and extend the toes, the major nerves (posterior tibial and peroneal) to the lower extremity are intact. If a neurologic or vascular impairment is present, it is often relieved by reduction of the fracture or dislocation. If a neurologic impairment persists following the reduction, it is usually treated by simple observation and exercises to prevent contractures. The prognosis is generally good for complete recovery. Circulatory impairment that persists requires immediate vascular evaluation. The initial neurologic examination is particularly important because if a deficit is discovered only after treatment, it may not be able to be determined whether it was present before or occurred as a result of treatment.

Table 2-1 Occasional Neurovascular Complication of Common Injuries

| Bony Injury | Lesion | Prominent Early Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Anterior shoulder dislocation | Circumflex axillary nerve injury | Mid-deltoid numbness |

| Spiral fracture of humerus | Radial nerve injury | Wrist drop |

| Avulsion fracture of medial epicondyle | Ulnar nerve injury | Numbness of small finger, weak finger abduction, adduction |

| Severe elbow fracture | Brachial artery injury | Severe pain, pain on passive finger extension |

| Fractured distal radius, ulna | Median or ulnar nerve injury | Numbness, motor loss |

| Posterior dislocation of hip | Sciatic nerve injury (usually peroneal portion) | Foot drop, weak extensor hallucis longus, numbness on dorsum of foot or great toe |

| Fracture of upper fibula | Peroneal nerve injury | Same |

| Fracture of upper tibia | Compartment syndrome | Severe pain, pain on passive stretch of involved compartment muscles |

Definitive Fracture Care

Some fractures require no treatment or, at most, simple restriction of activity with a sling or crutches (Table 2-2). Many other fractures are treatable by cast immobilization without the need for reduction. Fractures that need to be reduced are usually treated by one of four general methods: (1) open or closed reduction with internal fixation, (2) continuous traction usually followed by cast immobilization, (3) closed reduction with external skeletal fixation, or (4) closed reduction followed by cast immobilization.

Table 2-2 Common Fractures Not Requiring Cast Immobilization*

| Fracture | Treatment |

|---|---|

| Impacted surgical neck of humerus | Shoulder immobilizer |

| Undisplaced radial head fracture | Sling |

| Undisplaced olecranon | Sling |

| Undisplaced patella | Knee immobilizer |

| Shaft of fibula | Crutches |

| Base of fifth metatarsal | Hard sandal |

| Stress fracture | Avoid offending activity |

| Toe phalanges (undisplaced) | Tape to adjacent toe |

| Undisplaced calcaneus | Crutches |

* These fractures are stable and should not displace if the extremity is moved. A soft compression dressing for the first 2 to 3 days may be helpful in some cases.

OPEN OR CLOSED REDUCTION WITH INTERNAL FIXATION

Closed rather than open treatment of most fractures is usually preferred to avoid stripping the soft tissue and periosteum and devascularizing the bone ends. Closed treatment also decreases the chance of infection. There are several fractures, however, in which accurate anatomic positioning of the fragments and rigid internal fixation are beneficial: (1) displaced joint fractures, especially the weight-bearing joints; (2) fractures that cannot be reduced or held by closed methods; (3) fractures of the lower extremity in the elderly to allow early activity; (4) certain epiphyseal fractures that could result in a growth disturbance if not accurately reduced; and (5) joint fractures in which early motion would be helpful to prevent stiffness.

THE ELEMENTS OF CLOSED REDUCTION

Most common fractures can be treated by manual reduction and immobilization, but for this procedure to be successful, certain mechanical aspects of the fracture should be understood. Whenever a bone has been broken and the fractured ends separate, the soft tissue (mainly periosteum) on the side opposite the direction of displacement ruptures and allows the fracture to angulate and rotate (Fig. 2-8). The tissue on the side to which the displacement occurs remains intact, although it may be stripped off of the bone. This intact soft tissue forms a “hinge” that can be used in the treatment of many fractures to help guide the displaced distal fragment or fragments into place and to help maintain that position.

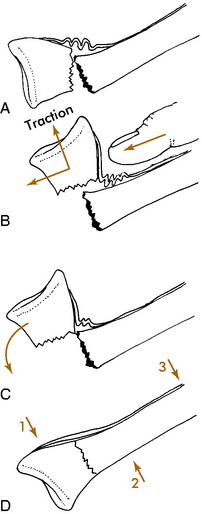

Many methods can be used to place bones back into their original position. Most of these require that the distal fragment be placed into apposition to the proximal one. Some fractures require only a “push” back into place (Fig. 2-9). Others need a more complicated maneuver that incorporates traction and manipulation of the fragments (Fig. 2-10). The nature of the fracture and its displacement determine which method is necessary.

Before any reduction is attempted, each fracture should be thoroughly studied and a complete mental plan developed. This plan should include every detail in the manipulation, including where the operator will be positioned, how the extremity will be grasped and held, and where the assistant should be positioned. In general, most reductions are accomplished as follows: (1) a variable amount of traction is applied to the distal fragment with countertraction on the proximal fragment; (2) the deformity is increased, if necessary (reproduce the injury), and rotational misalignment is then corrected; (3) the distal fragment is then reduced and the angular deformity corrected. The periosteal hinge will usually prevent overreduction. A cast is then applied to hold the position. The cast should be properly molded to prevent recurrence of the deformity in the cast by keeping tension on the soft tissue hinge and prevent recurrence of the deformity in the cast (see Fig. 2-10, D). Even casts that are applied to undisplaced fractures should be molded to avoid the loss of position that occasionally occurs in spite of protection (Fig. 2-11).

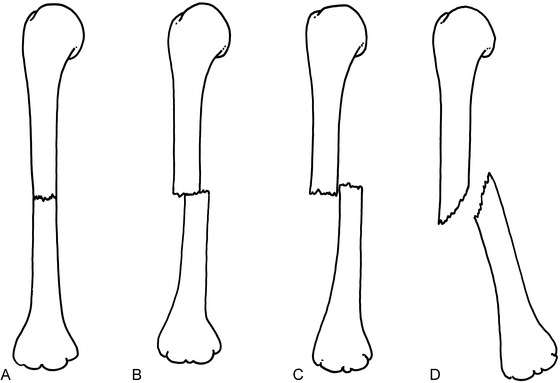

Fig. 2-11 A, An undisplaced fracture of the distal radius treated with a loosely fitted cast. B, Marked posterior angulation present at the time of cast removal. (Fortunately, the deformity was expected to correct with growth.)

EXTERNAL IMMOBILIZATION

Some physicians occasionally prefer splints (usually anterior and posterior) to circular casts as primary care to avoid possible circulatory and swelling complications. These splints are sometimes called “sugar tongs” if the units are continuous. The splint system, shaped like an elongated U, is held in position by gauze or an elastic bandage (Fig. 2-12). It can be easily loosened or tightened if needed. Always apply cast padding to the limb first.

Fig. 2-12 The sugar tong splint. It is made from a long continuous piece of padded plaster or fiberglass splint material, usually 3 or 4 inches wide, and extends from the palm around the elbow to the dorsum of the hand. Always apply circular cast padding around the limb first. Roller gauze or elastic bandage is applied over the splint to secure it in place. Similar splints can be used to stabilize ankle injuries and even humeral fractures.

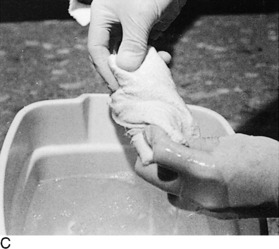

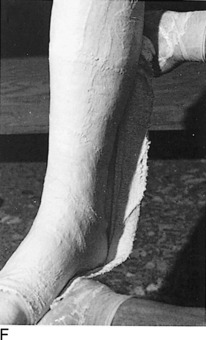

Whenever a cast is used, the extremity should always be held in the position of function while the cast is being applied, unless the extremity must be positioned otherwise, such as for maintenance of fracture position (Fig. 2-13). Casts are always applied in the same orderly sequence. The assistant holds the extremity in the proper position, and a single layer of stockinette, although not always necessary, may be applied (Fig. 2-14). Cast padding is then applied, beginning at one end and proceeding to the other to a double thickness by overlapping the roll 50% each turn. Do not overpad because the cast will be loose, but do place “donut” pads over bony prominences or other areas of concern (peroneal nerve at the fibular neck, ulnar styloid, both malleoli, and the olecranon process).

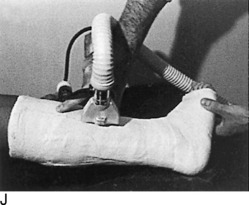

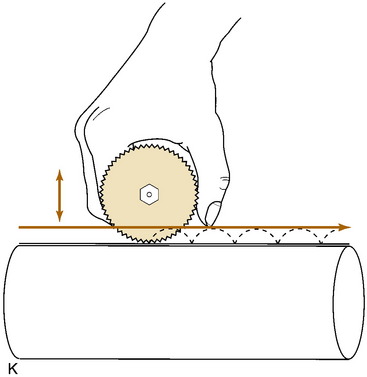

Fig. 2-14 The cast. A, A stockinette may first be applied. Any folds in front should be trimmed. B, Beginning at one end, cast padding is added while overlapping each roll by half. C, The plaster is removed from the water after the bubbles cease. The ends are pinched shut, and the roll is gently squeezed to expel excess water. Less water or excess wringing causes faster drying. Using the larger sizes may help avoid premature drying of the roll. Wet plaster makes a smoother cast. D, Beginning at one end, the plaster is pushed onto the extremity by using gentle pressure by the thenar eminence against the middle of the roll. The roll should remain in contact with the limb and is usually not lifted from it. Additional rolls are started where the last one ended. The roll is applied so that the opening side faces the operator and not the extremity. Rolling is continuous, and each layer is rubbed so that all layers fuse together. The short leg cast should always extend under the metatarsal heads for support. E, Tucks or pleats are taken as often as necessary to guide the roll and to accommodate any tapering of the limb. The stockinette is folded back and incorporated into the cast. F, Reinforcing splints five to ten layers thick applied to the sides or back add a great deal of strength without adding much weight. They are particularly useful at the ankle, where the cast is weakest and breakage is most common. G, The cast is molded with the flat surface of the hands, if necessary, and trimmed, especially at the small toe. H, Cast boots function better than walking heels; there are fewer repairs and a better gait. Wait 48 hours for the cast to cure before allowing weight bearing on plaster (1 hour for lightcast). I, Roentgenogram of a portion of a short arm cast showing a cast of even thickness without excessive padding between the cast and the skin. J and K, Casts are removed with the cast saw and spreader. The cast is removed by cutting down through both sides. Do not saw back and forth with the blade. It is better to pick the blade up and move it every time the plaster is cut through. Counterpressure with the thumb and/or index finger on the cast will prevent the blade from injuring the underlying skin. Cut the cast at right angles to the material. Sharp blades cut easier with less force and therefore less potential for skin injury. A hot blade may mean a dull blade. While cutting, the cast may be pulled or pushed away from the skin to give more room. Edema that holds the limb against the cast or the presence of soft rheumatoid skin may increase the chance of the cast saw abrading the skin. L, The sectioned cast showing even, fused plaster that is properly contoured and molded. It is as thick at the end as it is in the middle. The use of wider rolls will result in a more even cast than the use of many small rolls. Two 4-inch rolls of plaster will suffice for an adult short arm cast (or two 2-inch rolls of Lightcast). Three 6-inch rolls are necessary for an adult short arm cast (or three 4-inch rolls of Lightcast).

The cast should be of uniform thickness, about 0.6 cm. No two turns should be made at the same spot, except at the ends of the cast. Thus, the plaster is applied evenly end to end and will not be any thicker at the fracture site than elsewhere. Each layer should be applied moist to allow each turn to bond to the next layer. If this does not occur, a cast results that is several individual layers thick rather than one single thickness. The plaster should be worked and smoothed during the application of each layer.

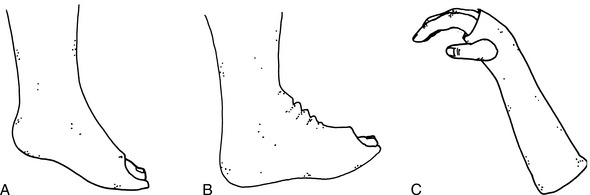

AFTERCARE

It is often difficult to differentiate among fracture pain, acute compartment syndrome, arterial injury, and nerve palsy, especially in an anxious patient. Peripheral nerve testing will usually rule out nerve palsy, and if peripheral pulses are present, arterial injury is unlikely. The acute compartment syndrome is a condition that develops when perfusion of nerve and muscle decreases to the point where it is unable to sustain viability. Pressure inside the natural fascial compartments of the arm or leg may rise, usually because of fracture bleeding, which then obstructs venous outflow. This leads to a further increase in tissue pressure and necrosis, sometimes within a few hours. A compartment syndrome should be suspected if there is (1) pain on passive stretching of the muscles of the affected compartment, (2) paresthesias or sensory loss, and (3) tenseness of the involved compartment. Paralysis may also occur. Arterial injury or compartment syndrome secondary to swelling in a tight cast could lead to Volkmann’s ischemic contracture if untreated (Fig. 2-15). This is a rare complication and most commonly occurs after severe elbow injuries, high tibial fractures, and metatarsal fractures. It is considered a surgical emergency.

REHABILITATION

After cast removal, active mobilization of joints that were immobilized by the cast is begun. A repetitive exercise that the patient may perform at home is preferable to most forms of physical therapy. Exercise in a swimming pool is an excellent method of restoring strength, mobility, and confidence after many injuries. Most extremities are able to regain most of their motion and strength within 4 to 6 weeks after the cast has been removed, but it is not uncommon for some stiffness, weakness, and swelling to persist longer. Formal physical therapy is usually unnecessary.

ADDITIONAL PRINCIPLES

Fractures in Children

PRINCIPLES OF TREATMENT

Fig. 2-16 A, Fracture of the upper portion of the humerus in a 6-year-old patient. An attempt was made to reduce the fracture, but the position could not be improved and was accepted. B, The same patient approximately 10 months later. Although the two roentgenograms are not in the same position of rotation, the remodeling and realignment are obvious.

THE EPIPHYSEAL PLATE

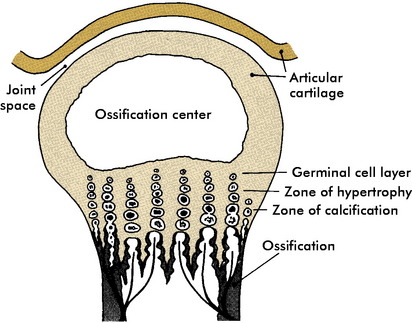

Two types of epiphyses exist in growing bones: the pressure epiphysis and the traction epiphysis (apophysis). Pressure epiphyses occur at the ends of long bones and contribute to the longitudinal growth of the bone. Traction apophyses, such as the iliac crest and trochanters of the hip, contribute primarily to the contour of the bone and little to actual longitudinal growth. They are present at the attachment of major muscles and respond to traction rather than to pressure. The epiphyseal plate itself consists of several zones or layers (Fig. 2-17). The zone nearest the joint is the germinal cell layer. Moving away from the joint are the zone of proliferation, the zone of hypertrophic cartilage, and the zone of provisional calcification. Epiphyseal fractures may be categorized according to the type of injury, the relationship of the fracture line to the germinal cell layer, and the prognosis. Salter’s classification is commonly used.

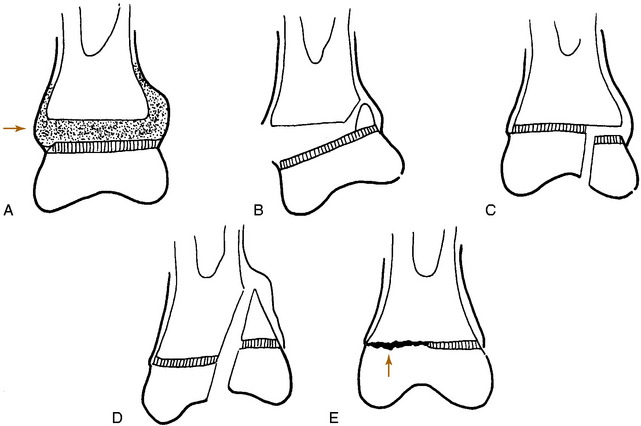

Fig. 2-17 The epiphyseal plate. Most epiphyseal fractures occur through the zone of hypertrophic cartilage.

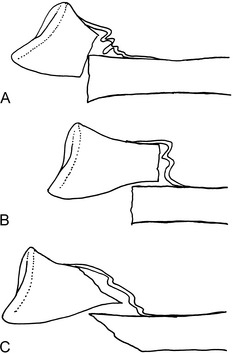

Most epiphyseal fractures occur irregularly through the weakest zone, the zone of hypertrophic cartilage. They are usually transverse and do not travel vertically across the germinal cell layer. These fractures are classified by Salter and Harris as type I or type II, and the prognosis for normal healing is good (Fig. 2-18). Manipulative reduction is usually successful. Overzealous attempts to correct minor persistent deformities during the reduction should not be made because these mild deformities usually correct themselves with growth. Further damage to the growth plate may be caused by overaggressive treatment.

Fractures that do traverse the growth plate vertically (types III and IV) may disturb the growth, causing an angular deformity to develop as growth continues. Cross-union may even occur across the epiphyseal plate, leading to complete cessation of growth. These fractures are also frequently intraarticular, and accurate reduction is mandatory to prevent growth disturbance from occurring and to restore the joint surface. Surgery is usually necessary to accomplish these goals. Type V fractures are crush injuries that have a poor prognosis (Fig. 2-19). Frequently, no definite fracture line is visible.

Fractures Requiring Special Care

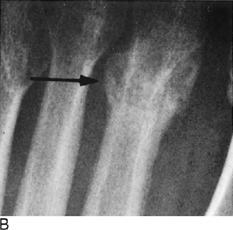

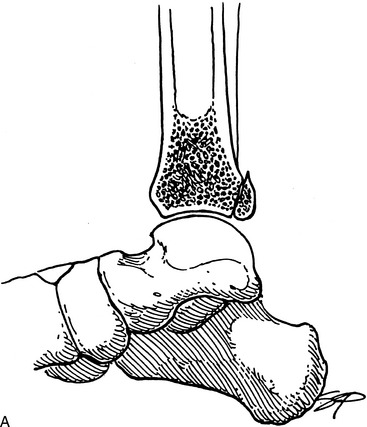

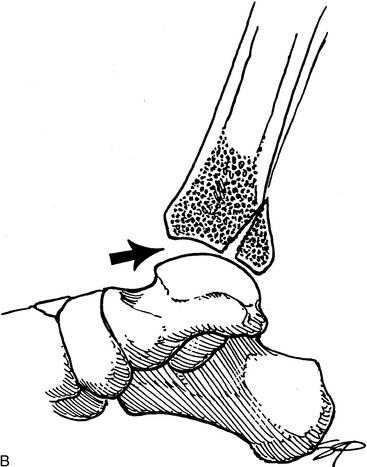

Fig. 2-20 Articular fracture. Small articular fractures (A) usually do not produce instability or allow subluxation. B, If the fragment is greater than 25% of the joint surface, subluxation may occur (arrow), creating an irregular articular surface which may eventually lead to arthritis. C, A lateral view of the ankle revealing a large (triangles), displaced fragment (curved arrow) that should be surgically repaired.

| Fracture | Complication |

|---|---|

| In Children | |

| Supracondylar fracture of the humerus (displaced) | Volkmann’s contracture, malunion |

| Lateral condylar fracture of the humerus | Nonunion, cubitus valgus, late ulnar nerve paralysis |

| Epiphyseal fractures III, IV, and V | Growth disturbance |

| Radial neck and head fracture | Growth disturbance |

| In Adults | |

| Fracture of both bones of the forearm (displaced) or displaced single forearm bone | Malunion, nonunion, restricted forearm rotation |

| Displaced bimalleolar fracture | Nonunion, traumatic arthritis |

| Supracondylar, intercondylar fracture of the humerus | Traumatic arthritis, joint stiffness |

| Displaced olecranon fracture | Nonunion |

| Displaced radial head fracture | Traumatic arthritis, joint stiffness |

| Fractured upper tibia | Acute compartment syndrome |

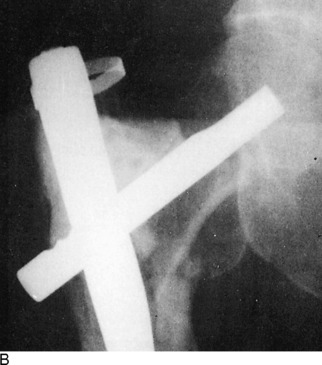

Pathologic Fractures

Pathologic fractures develop because of some abnormal local condition that causes the bone to become weakened. The most common causes are tumors that metastasize to bone. Other causes are infection, cystic lesions of bone, and Paget’s disease. With the increase in the survival rate of cancer victims, there has also been an increase in the incidence of pathologic features. To maintain the highest possible level of function in patients, aggressive management of these fractures is frequently indicated. The treatment is usually surgical (Fig. 2-21). Operative procedures are especially indicated in the lower extremities to encourage ambulatory activities. Although radiation therapy may relieve the pain, it can actually impede fracture healing. By stabilizing the fracture surgically, immediate use of the extremity is frequently possible. This is accomplished by curetting the tumor, filling the resultant cavity with methyl methacrylate cement, and adding the appropriate internal fixation device. The procedure is often performed on a prophylactic basis.

Fractures of the Battered Child

The injuries may be visceral, cranial, or musculoskeletal. The characteristic musculoskeletal lesions are (1) multiple bony lesions, frequently epiphyseal fractures, in various stages of healing, and (2) excessive periosteal reaction indicative of recent trauma with or without fracture (Fig. 2-22).

Stress Fractures

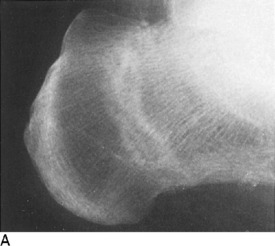

Stress fractures are incomplete fractures. They are often described as either insufficiency or fatigue fractures. Insufficiency fractures may occur when normal stress is applied to weak bone (see Chapters 9 and 10). Fatigue fractures may develop when excess stress is applied to normal bone. Either type may occur in any weight-bearing bone, but they are most common in the metatarsal (“march” fracture), neck of the femur, calcaneus, tibia, fibula, and pelvis. Osteoporosis is the most common cause of insufficiency factures.

The roentgenogram is usually normal early in the disorder, although a bone scan would be positive. If this condition is suspected, treatment is instituted, and roentgenograms are repeated at 2-week intervals (Fig. 2-23). An obvious fracture line is not usually apparent. A healing stress line is generally seen in 2 to 4 weeks. Exuberant periosteal bone formation may even simulate malignancy. Stress fractures in cancellous bone usually produce only a sclerotic transverse line without periosteal reaction. In cortical bone, however, there is generally considerable formation of periosteal new bone.

Electrical Stimulation of Bone Healing

In the early 1950s, it was demonstrated that bone exhibits a separation of charge when it is placed under stress. The side of the bone under compression becomes electronegative, and the side under tension becomes electropositive, thus creating an electrical potential. This is known as the piezoelectric effect. As a result of the findings, researchers began studying the effects of electricity on bone and cartilage. It was found that delivery of the proper amount of voltage and current by electrodes can stimulate osteogenesis.

Blount WP. Fractures in children. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1955.

Carty HML. Fractures caused by child abuse. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1993;75:849-857.

Charnley J. The closed treatment of common fractures, ed 3. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1970.

Connolly JF. Fracture complications. Chicago: Year Book Medical Publishers, 1988.

Flatt AE. The care of minor hand injuries, ed 3. St. Louis: CV Mosby, 1972.

Kocher MS, Kasser JR. Orthopaedic aspects of child abuse. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2000;8:10-20.

McLaughlin HL. Trauma. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Co, 1959.

Pool C. Colles’s fracture. A prospective study of treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1973;55:540-544.

Rang M. Children’s fractures, ed 2. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott, 1983.

Rockwood CA, Green DP. Fractures in adults, ed 2. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott, 1984.

Sim FH. Metastatic bone disease: philosophy of treatment. Orthopedics. 1992;15:541-544.

Thompson RC. Impending fractures associated with bone destruction. Orthopedics. 1992;15:547-557.

Zionts LE. Fractures around the knee in children. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2002;10:345-355.