24.2 Fractures and dislocations

Fracture patterns in childhood

In the previous chapter the impact of development (behavioural and physiological) on musculoskeletal pathology was broadly outlined (see Table 24.1.1). With respect to injury, this means different points of cleavage or deformation from a given injury mechanism, and an extra anatomical structure (the physis) to consider when analysing the effects of trauma and the future outcome of a given disruption.

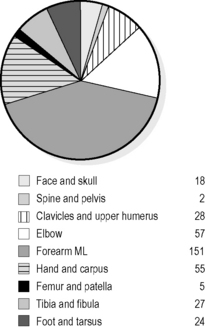

Fig. 24.2.1 shows the frequency of common fractures presenting to a children’s emergency department (ED). Within different age subgroups, the distribution varies thus:

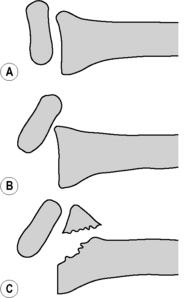

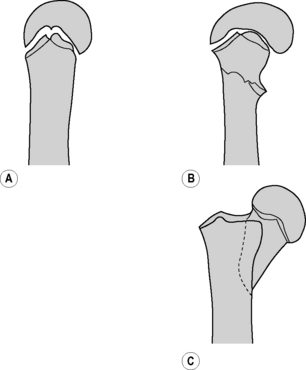

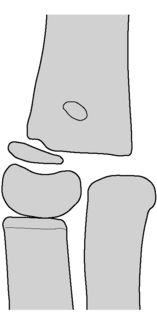

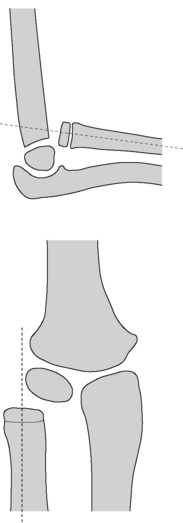

Paediatric limb fractures, depending on the angle of force to which they have been subjected, can occur to shaft, metaphysis, or physeal region. The different quality of developing bone means that even injuries to shaft and metaphysis tend to have different patterns of deformation, including ‘torus’ or buckle injuries, bowing, and greenstick fractures. The importance of this awareness for the emergency physician is best illustrated by the Monteggia equivalent injury in which ‘shortening’ from proximal radial dislocation is ‘matched’ by ulnar bowing. The resultant injury has no radiologically obvious ‘fracture’ in the traditional sense but has serious consequences if not recognised and reduced (Fig. 24.2.2).

Fig. 24.2.2 Monteggia fracture-dislocation. Demonstration of the abnormal radio-capitellar relationship (see Fig. 24.2.8 for contrast).

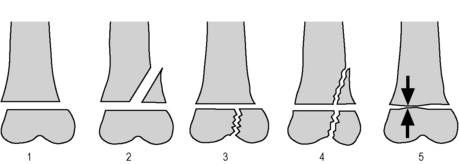

The Salter–Harris classification (Fig. 24.2.3) remains the most useful way of describing the pattern of cleavage with respect to the physis. In reality, types 1 and 5 represent mechanical force patterns (separation and compression) rather than a radiological pattern as, unless there is lateral translation or adjacent bony or soft-tissue deformation, the physis may appear radiologically normal in these injuries. An example of Salter–Harris type 1 injuries with lateral shift is the so-called ‘slipped distal radial epiphysis’ (Fig. 24.2.4). The disorder of slipped upper femoral epiphysis (SUFE) has been discussed in Chapter 24.1 as, although minor trauma may precipitate an acute slippage, the cleavage is due to an abnormal physeal predisposition and should not be looked upon as truly traumatic.

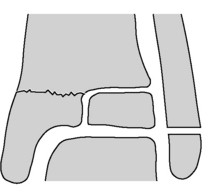

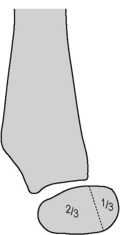

Salter–Harris type 2 injuries are the most common physeal injury pattern seen, the metaphyseal corner (the ‘Thurston-Holland’ fragment) ranging in size from a barely visible fragment to an extensive triangle. Injuries through the epiphysis itself, Salter–Harris types 3 and 4, are more worrying in their prognosis because they are intra-articular as well as involving the physis. The classic example of a Salter–Harris type 3 injury is the Tillaux fracture (Fig. 24.2.5), while lateral condylar fractures at the elbow are Salter–Harris 4 in type.

Table 24.2.1 shows some examples of the corresponding injury occurring in adults and children for a given mechanism. This table illustrates the maxim that children tend to fracture rather than ‘sprain’, as the physis is the weakest point of the musculoskeletal continuum, i.e. a ligament will avulse its bony origin or insertion rather than tearing. In some cases, this is to the child’s advantage, as the cellular architects of bone development which contribute to its mechanical weakness contribute to rapid healing and extensive remodelling. A midshaft femoral fracture, for example, will heal in 2–3 weeks in an infant, whereas the same disruption will take 12 weeks to union in a teenager.

Initial assessment and management

The initial assessment of the paediatric isolated limb injury (fracture/dislocation) is shown in Table 24.2.2 and the neurovascular assessment in Table 24.2.3. Limb injury must always be considered in the broader context of trauma. Primary and secondary survey, however brief and targeted, should always be carried out bearing in mind the described injury mechanism and the child’s complaints of pain, so that any associated injuries, e.g. to head, abdomen, or spine, may be recognised and evaluated early. An efficient early assessment should be able to establish mechanism, possible other sites of injury, probable fracture type, presence or absence of compound features or neurovascular impairment, and organise pain relief, fasting, radiology, splintage, and antibiotics if required, within a brief period.

|

Sensation thenar eminence, action = opposition, flexion IP thumb (supracondylar # or elbow dislocation)

|

In general, fractures in pre-verbal children without a clear, developmentally appropriate mechanism/history or with other concerning features, will need further assessment. Features suggestive of non-accidental injury are shown in Table 24.2.4, and child abuse is discussed in more detail in Chapter 18.2. As a minimum, all fractures occurring in children under 12 months should be discussed with a paediatrician or child-protection specialist.

| Fractures |

| Presentation features |

| Assessment |

| Rule of thumb |

| Refer |

Upper limb and shoulder girdle injuries

Proximal humerus

These fractures vary from minor buckling at the proximal metaphysis, to proximal humeral epiphyseal Salter–Harris type 2 fracture-separations (Fig. 24.2.6). Because of the universal motion at the glenohumeral joint and the remodelling potential of children, a remarkable range of initial traumatic deformity is acceptable in children prior to physeal closure (age 14–16), including complete displacement and up to 60 degrees of angulation.2 A collar and cuff is the usual treatment.

Injuries to the elbow region

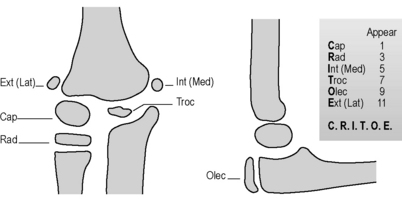

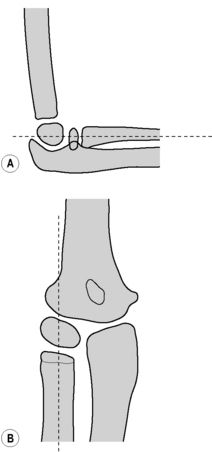

The elbow region accounts for 10% of all paediatric fractures. Supracondylar fractures make up 75% of these, and lateral condylar fractures 17%.3 Missed or inadequately treated paediatric elbow injuries figure prominently in orthopaedic litigation series.4 Post-traumatic elbow effusion in childhood without a radiologically apparent fracture line most commonly represents a minimally displaced supracondylar fracture. These must be immobilised by collar and cuff to avoid any potential extension from further falls, and followed up in a fracture clinic for a repeat X-ray at 7–14 days. It is sometimes useful to start with the examination findings in the normal elbow, as outlined in Table 24.2.5 (Figs 24.2.7 and 24.2.8). The first point in itself will define an anatomically intact elbow, while the other points help the physician to narrow down the type of abnormality where the first point is abnormal.

Supracondylar fracture

Gartland Type 2 – posterior angulation with probable intact periosteal hinge (Fig. 24.2.9A)

In this situation it is important to check for associated rotation or varus/valgus injury. Use the ‘anterior humeral line’ as a guide to the degree of posterior angulation (Fig. 24.2.10), and consult orthopaedics about all injuries. Simple (2a) fractures with less than 20 degrees of angulation may be managed conservatively in a backslab and collar and cuff, with orthopaedic follow up. If there is varus/valgus angulation or rotation on the AP view (Gartland Type 2b), then orthopaedic consultation is required acutely as surgery may be indicated. Remember that remodelling may correct some loss of flexion or extension but will not correct rotation or varus/valgus deformity.

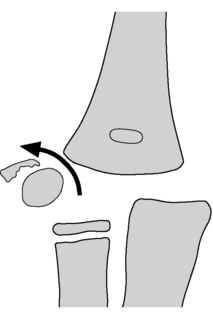

Lateral condyle

This fracture results from a varus force on the supinated forearm, avulsing the condyle (Figs 24.2.11 and 24.2.12). There is clinical swelling and tenderness, which is maximal over the lateral condyle. It is usually a Salter–Harris type 4 fracture, but the late appearance of the trochlear and lateral epicondylar ossification centres means that the true structural disruption is not demonstrated by radiology, and therefore not appreciated by emergency staff, particularly in the younger child. The varus angulating force characteristically causes disruption commencing above the lateral condyle, passing to a varying extent along the physis, and in complete disruptions exiting either lateral (in the majority of cases; Milch type 1), or medial (Milch type 2) to the capitellar-trochlear groove. If uncorrected, the injury may result in valgus deformity, and possible delayed ulnar nerve palsy and degenerative elbow disease.

Fig. 24.2.12 Displaced and rotated lateral condylar fracture (Milch type I).

Long-term complications may ensue if not surgically fixed.

Drawing by Terry McGuire.

Bony displacement is often best seen on the lateral X-ray.

The clinical significance of this fracture means that:

Any lateral condyle fracture with a greater than 2 mm separation of fracture segments is likely to require internal fixation, particularly if displacement is proximal.

Any lateral condyle fracture with a greater than 2 mm separation of fracture segments is likely to require internal fixation, particularly if displacement is proximal. All young children with major elbow deformity/swelling as a result of injury should be assessed early by experienced orthopaedic personnel. Ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging, and arthrography may all have a role to play in determining the line of injury and consequent best means of fixation. Within the ED, an internal oblique radiograph can be helpful.

All young children with major elbow deformity/swelling as a result of injury should be assessed early by experienced orthopaedic personnel. Ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging, and arthrography may all have a role to play in determining the line of injury and consequent best means of fixation. Within the ED, an internal oblique radiograph can be helpful.Medial epicondylar avulsion

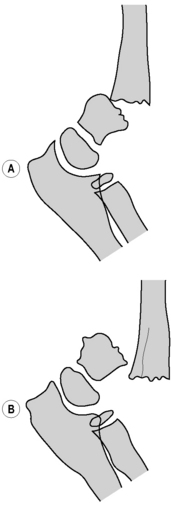

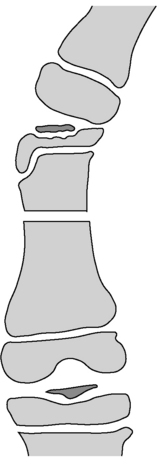

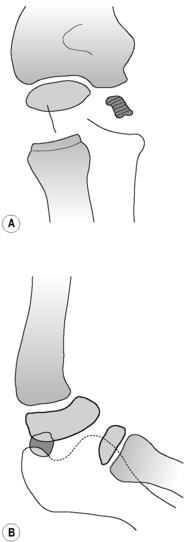

This may occur in association with other disruptions, e.g. elbow dislocation, or as a discrete event (Fig. 24.2.13). The medial epicondyle is the origin of the common flexor tendon, and ossifies at approximately age six. It will generally reunite readily with the humerus if it lies within 5 mm, unless there is interposing tissue. Occasionally, particularly when the avulsion has occurred in association with a posterior elbow dislocation, the epicondyle and its attachments may become lodged within the elbow joint and may block an attempt at closed reduction. Ulnar nerve injury is a common association. This circumstance is one of the main practical uses of knowledge of elbow ossification centres (see Fig. 24.2.7). These must be systematically reviewed on every elbow X-ray so that missing or misplaced opacities may be identified.

Fig. 24.2.13 Medial epicondylar avulsion.

(A) The opacity below the humerus is the avulsed medial epicondyle, which should be sitting more proximal and medial. There should not be a trochlear opacity without a medial epicondylar ossification centre. Developmentally, there should not be an ossification centre in the trochlea position without one in the medial epicondylar position. (see Fig. 24.2.7). (B) Lateral view shows opacity ‘between’ capitellum and olecranon, possibly intra-articular.

Drawing by Terry McGuire.

Pulled elbow (radial head subluxation, RHS)

Subluxation occurs because the oval shape of the radial head allows the head to sublux slightly through the annular ligament when the forearm is pulled in pronation. Part of the ligament is ‘caught’ in the radiocapitellar space, and in fact partial tears can occur.5,6 In older children the ligament is thicker and more densely attached, and subluxation in a child over 5 is unusual.

Reduction of RHS

A recent prospective randomised trial has suggested that hyperpronation is more likely than supination to reduce the pulled elbow on the first occasion, and elicits less discomfort.7

After a brief parental explanation and oral or intranasal pain relief, these children should be held firmly by a parent while the forearm is hyperpronated. It is helpful for the doctor to cradle the elbow in the outer hand with the thumb over the radial head while their inner arm rotates. Success is usually denoted by a momentary pain, a palpable click, and a return to functional use. If the procedure is not successful, the procedure can be repeated, and if this fails, the traditional method of full, firm supination and flexion can be attempted. This combination of techniques should elicit success in >90% of cases of radial head subluxation.7 If the above process is unsuccessful, the history and examination should be revisited and imaging sought. Interestingly, while radiographs should be normal (and should not show posterior fat pad elevation, which should suggest alternative diagnoses), the radiocapitellar distance is significantly increased in radial head subluxation on ultrasound due to the presence of the interposed ligament; a tear may sometimes be shown. If an alternative diagnosis is not suggested by imaging and careful re-assessment, RHS remains the most likely diagnosis: the child can be allowed home with the arm supported in a sling in a neutral position, and with review at 24-48 hours, at which time many will have spontaneously reduced. Persistent dysfunction beyond 48 hours requires orthopaedic evaluation. Although some children sustain recurrent RHS, it rarely requires operative intervention.8

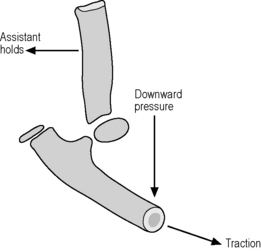

Elbow dislocation

The dislocation should be suspected clinically. After assessing for associated injuries, it should be reduced in the ED, generally under ketamine anaesthesia (Fig. 24.2.14). Gentle downwards pressure can be applied to the supinated proximal forearm, with extension of the elbow to about 135 degrees, against countertraction to distal humerus. Full extension should be avoided as it may cause further damage to the ulnar nerve. If there is difficulty in resiting the olecranon, there may be soft tissue inter-position and orthopaedic help should be sought, as a computerised tomography (CT) scan may be indicated. The reduced elbow should be held in flexion with a posterior splint, a check X-ray performed, and orthopaedic follow up arranged.

Monteggia fracture dislocation

The peak incidence of this injury complex is in the 4–10 age group. Although, classically, radio-capitellar disruption accompanies an angulated or shortened ulnar fracture, the displacement may occur in association with any displacement to the radioulnar loop. Because of the significant complications of a missed radio-capitellar disruption, this lesion must be actively clinically and radiologically sought in any child with a forearm fracture and elbow swelling. Most units adopt a rule of always X-raying the elbow of any child with forearm or wrist injury, unless the elbow has been specifically clinically cleared (see Table 24.2.5).

The classical (Type 1) Monteggia lesion involves an angulated apex-volar ulnar shaft fracture and anterior displacement of the radial head (see Fig. 24.2.2). Variants include lateral radial head displacement, often in association with proximal ulnar/olecranon fractures (Type 3), ‘Monteggia equivalent’ fractures including proximal radial fracture/dislocation, and others. A bowing deformity may be the only evidence of fracture. Orthopaedic manipulation of the radial head into its articulation is the aim of the treatment.

Distal radial and ulnar fractures

Again, attention must be paid to ensure that a well-moulded plaster will maintain reduction, and follow-up orthopaedic review should be early enough to detect this and remanipulate if necessary i.e. within 1 week. Early orthopaedic referral should occur for angulated isolated radial fractures and for fractures of radius and ulna with complete displacement and shortening, as a significant proportion of these manipulations will be problematic or require internal fixation.11

Distal radial epiphyseal fractures

These can generally be treated by manipulation and closed reduction in the same way as metaphyseal fractures. There is a very low incidence of subsequent premature physeal closure or other physeal disruption. This risk is greatest following multiple or delayed reduction attempts, or compressive injuries, or distal physeal separation of the ulna.2 Following manipulation, referral to fracture clinic must be within a week as repeat manipulation of the physis is contraindicated after 7 days.

Carpal injuries: the scaphoid

Because of the flexibility of the paediatric wrist and the plastic properties of preossified bone, carpal injuries are very rare in children under 8 years. Scaphoid injuries are generally overdiagnosed in children in the ED setting. Of those fractures that do occur, 65% are distal pole and non-union is rare because of the different mechanical and vascular properties of immature bone. As children reach adolescence, their risk of adult-type scaphoid fractures increases. Scaphoid views (AP and oblique with attention to possible obliteration of the navicular fat pad) are suggested in older children if:12–14

Lower limb and pelvis injuries

Hip dislocation

This is uncommon in childhood, occurring either with low force as a result of increased ligamentous laxity, or in the high-force mechanisms more typical of adult hip dislocation. The sequel of avascular necrosis is less common, occurring in only about 5% of cases.2 Reduction, by gentle closed longitudinal traction against a fixed pelvis, should be performed within 6 hours. Particular care must be taken in the adolescent in whom an occult physeal injury may be displaced. Post manipulation X-rays ± CT are indicated.

Femoral fractures

Types of femoral fracture in children, and their orthopaedic implications, are as follows:

Injuries about the knee

Tibial spine injury

Because of the mechanical properties of developing bone, twisting injuries to the paediatric knee result in avulsion of the tibial attachment of the anterior cruciate ligament (Fig. 24.2.15). The child presents non-weight-bearing, with a large effusion and joint-line tenderness. Although AP X-ray may be deceptive, lateral projections show a characteristic beak-like appearance of the superior surface of the tibial plateau, with posterior hinging. All children with large effusions should be referred for orthopaedic evaluation. Orthopaedic management involves an assessment, generally under anaesthetic, of the reducibility of the avulsed spine and the likelihood of, e.g. meniscal interposition. Treatment options include immobilisation in extension or partial flexion, and internal fixation. Some degree of subsequent instability and loss of extension may follow.

Lower leg fractures

Lower leg fractures are common in childhood. Factors to be considered in their assessment include:

Compound injuries and those with physeal involvement or significant angulation or displacement should be referred for inpatient orthopaedic evaluation. Proximal tibial epiphyseal injury may be complicated by vascular compromise, as with adult knee dislocation. Varus or valgus deformity, particularly at the proximal tibia, may progress. Stable, undisplaced or minimally displaced oblique or spiral shaft fractures of the tibia may be placed in a well-moulded above-knee cast with the knee flexed to 90 degrees and the ankle in 15 degrees of plantar flexion.17 Admission is not required if swelling is minimal, mechanism is clear, and parents are sensible.

Controversy exists surrounding boundary issues between emergency medicine and orthopaedics. Who performs which reduction should be determined by consideration of safe, effective resource use between emergency and orthopaedic services. Structured opportunities for interdepartmental teamwork help reduce angst and improve systems and service quality.

Controversy exists surrounding boundary issues between emergency medicine and orthopaedics. Who performs which reduction should be determined by consideration of safe, effective resource use between emergency and orthopaedic services. Structured opportunities for interdepartmental teamwork help reduce angst and improve systems and service quality.Ankle fractures

Tillaux fracture

This is a Salter–Harris type 3 fracture at the distal tibial physis, occurring in adolescence after partial closure of the medial growth plate (see Fig. 24.2.5). External rotation of the foot and ankle causes avulsion of the anterolateral portion of the distal tibial physis by its attachment to the fibula (anterior tibiofibular ligament). The diagnosis should be suspected in a non-weight-bearing adolescent with significant anterolateral ankle swelling and tenderness. Oblique ankle views or CT assessment may be required to detail alignment.

Conclusions

Sprains are uncommon as the physis or ligamentous insertions are the ‘weakest chains’

The increasing trend to outpatient management of injuries will mean increasing numbers of paediatric fractures having definitive treatment in the emergency department. A thorough familiarity with paediatric fractures and their traps is essential, as is attention to quality assurance as discussed in Chapter 24.4.

Acknowledgement

The contribution of Terry McGuire as author in the first edition is hereby acknowledged.

1 Clark RC, Brady RM, Pitt WR, et al. Flagging possible abusive injury in young children: The role of the Injury Proforma. Abstract epublished in Emerg Med Australasia 2010 Feb

2 Morrisey R., Weinstein S. Lovell and Winter’s pediatric orthopedics, 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001.

3 Mater Children’s Hospital B. 2002 Fractures in children by EDIS discharge diagnosis. 2002. Sep–Nov 2002

4 United Medical Protection pc. Orthopaedic claims under 16 years over the period 1985-2002. 2003. In: RM B, ed. Brisbane: 2003

5 Kim M.C., Eckhardt B.P., Craig C., Kuhns L.R. Ultrasonography of the annular ligament partial tear and recurrent ‘pulled elbow’. Pediatr Radiol. 2004;34(12):999-1004. 12/27/

6 Kosuwon W., Mahaisavariya B., Saengnipanthkul S., et al. Ultrasonography of pulled elbow. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1993;75(3):421-422. 05

7 Bek D., Yildiz C., Kase O., et al. Pronation versus supination maneuvers for the reduction of ‘pulled elbow’: a randomized clinical trial. Eur J Emerg Med. 2009;16(3):135-138. 06

8 Triantafyllou S.J., Wilson S.C., Rychak J.S. Irreducible ‘pulled elbow’ in a child. A case report. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992;11(284):153-155.

9 Davidson J., Brown D., Barnes S. Simple treatment for torus fractures of the distal radius. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2002;84(7):1085.

10 Boyer B., Overton B., Scrader W., Riley P. Position of immobilisation for paediatric forearm fractures. J Pediatr Orthop. 2002;22(2):185-187.

11 Gibbons C., Woods D., Pailthorpe C., et al. The management of isolated distal radius fractures in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 1994;14(2):207-210.

12 Evenski A.J., Adamczyk M.J., Steiner R.P., et al. Clinically suspected scaphoid fractures in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 2009;29(4):352-355. 06

13 Hernandez J.A., Swischuk L.E., Bathurst G.J., Hendrick E.P. Scaphoid (navicular) fractures of the wrist in children: attention to the impacted buckle fracture. Emerg Radiol. 2002;9(6):305-308. 12/09/

14 Weber D.M., Fricker R., Ramseier L.E. Conservative treatment of scaphoid nonunion in children and adolescents. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91(9):1213-1216. 09

15 Thomas S., Rosenfield N., Leventhal J., Markowitz R. Long-bone fractures in young children: Distinguishing accidental injuries from child abuse. Paediatrics. 1991;88(3):471-476.

16 Hui C., Joughin E., Goldstein S., et al. Femoral fractures in children younger than three years: the role of nonaccidental injury. J Pediatr Orthop. 2008;28(3):297-302.

17 Yang J., Letts R. Isolated fractures of the tibia with intact fibula in children: A review of 95 patients. J Pediatr Orthop. 1997;17:347-351.