Foundations for clinical practice*

DARCY A. UMPHRED, PT, PhD, FAPTA, ROLANDO T. LAZARO, PT, PhD, DPT, GCS and MARGARET L. ROLLER, PT, MS, DPT

After reading this chapter the student or therapist will be able to:

1. Analyze the interlocking concepts of a systems model and discuss how cognitive, affective, sensory, and motor subsystems influence normal and abnormal function of the nervous system.

2. Use an efficacious diagnostic process that considers the whole patient/client and includes evaluation, examination, diagnosis, prognosis, intervention, and related documentation, leading to meaningful, functional outcomes.

3. Apply the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) to the clinical management of patients/clients with neuromuscular dysfunction.

4. Discuss the evolution of disablement, enablement, and health classification models, neurological therapeutic approaches, and health care environments in the United States and worldwide.

5. Discuss the interactions and importance of the patient, therapist, and environment in the clinical triad.

6. Consider how varying aspects of the clinical therapeutic environment can affect learning, motivation, practice, and ultimate outcomes for patients/clients.

7. Define, discuss, and give examples of a holistic model of health care.

A clinical problem-solving approach is used because it is logical and adaptable, and it has been recommended by many professionals during the past 40 years.1–7 The concept of clinical decision making based in problem-solving theory has been stressed throughout the literature over the past decades and has guided the therapist toward an evidence-based approach to patient management. This approach clearly identifies the therapist’s responsibility to examine, evaluate, analyze, draw conclusions, and make decisions regarding prognosis and treatment alternatives.8–24

This book is divided into three sections.

Roles that therapists are currently playing and will be asked to play in the future are changing.25–27 Therapists are experts in normal human movement across the life span (see Chapter 3) and how that movement is changed after life events, and with disease or pathological conditions. Therapists realize that health and wellness play a critical role in movement function as a client enters the health care system with a neurological disease or condition (see Chapter 2). In many U.S. states, clients are now able to use direct access for therapy services. In this environment, therapists must medically screen for disease and pathology to determine conditions that are outside of the defined scope of practice, and make appropriate referrals to other medical professionals (see Chapter 7). They must also make a differential diagnosis regarding movement dysfunctions within that therapist’s respective scope of practice (see Chapter 8). Section I has been designed to weave together the issues of evaluation and intervention with components of central nervous system (CNS) function to consider a holistic approach to each client’s needs (see Chapters 4, 5, 6, and 9). This section delineates the conceptual areas that permit the reader to synthesize all aspects of the problem-solving process in the care of a client. Basic to the outcomes of care is accurate documentation of the patient management process, as well as the administration and reimbursement for that process (see Chapter 10).

Section II is composed of chapters that deal with specific clinical problems, beginning with pediatric conditions, progressing through neurological problems common in adults, and ending with aging with dignity and chronic impairments. In Section II each author follows the same problem-solving format to enable the reader either to focus more easily on one specific neurological problem or to address the problem from a broader perspective that includes life impact. The multiple authors of this book use various cognitive strategies and methods of addressing specific neurological deficits. A range of strategies for examining clinical problems is presented to facilitate the reader’s ability to identify variations in problem-solving methods. Many of the strategies used by one author may apply to situations presented by other authors. Just as clinicians tend to adapt learning methods to solve specific problems for their clients, readers are encouraged to use flexibility in selecting treatments with which they feel comfortable and to be creative when implementing any therapeutic plan.16 Although the framework of this text has always focused on evidence-based practice and improvement of quality of life of the patient, the terminology used by professionals has shifted from focusing on impairments and disabilities of an individual after a neurological insult (the International Classification of Impairments, Disability and Health [ICIDH]) to a classification system that considers functioning and health at the forefront: the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF).28 The ICF considers all health conditions, both pathological and non–disease related; provides a framework for examining the status of body structures and functions for the purpose of identifying impairments; includes activities and limitations in the functional performance of mobility skills; and considers participation in societal and family roles that contribute to quality of life of an individual. The personal characteristics of the individual and the environmental factors to which he or she is exposed and in which he or she must function are included as contextural factors that influence health, pathology, and recovery of function.29 The ICF provides a common language for worldwide discussion and classification of health-related patterns in human populations. The language of the ICF has been adopted by the American Physical Therapy Association (APTA), and the revised version of the Guide to Physical Therapist Practice reflects this change.30 Each chapter in this book strives to present and use the ICF model, use the language of the ICF, and present a comprehensive, patient-oriented structure for the process of examination, evaluation, diagnosis, prognosis, and intervention for common neurological conditions and resultant functional problems. Consideration of the patient/client as a whole and his or her interactions with the therapist and the learning environment is paramount to this process.

Chapters in Section II also include methods of examination and evaluation for various neurological clinical problems using reliable and valid outcome measures. The psychometric properties of standard outcome measures are continually being established through research methodology. The choice of objective measurement tools that focus on identifying impairments in body structures and functions, activity-based functional limitations, and factors that create restrictions in participation and affect health quality of life and patient empowerment is a critical aspect of each clinical chapter’s diagnostic process. Change is inevitable, and the problem-solving philosophy used by each author reflects those changes.

Section III of the text focuses on clinical topics that can be applied to any one of the clinical problems discussed in Section II. Chapters have been added to reflect changes in the focus of therapy as it continues to evolve as an emerging flexible paradigm within a multiple systems approach. A specific body system such as the cardiopulmonary system (see Chapter 30) or complementary approaches used with interactive systems (see Chapter 39) are also presented as part of Section III. These incorporate not only changes in the interactions of professional disciplines within the Western medical allopathic model of health care delivery, but also present additional delivery approaches that emphasize the importance of cultural and ethnic belief systems, family structure, and quality-of-life issues. Two additional chapters have been added to Section III. Chapter 37 on imaging emphasizes the role of doctoring professions’ need to analyze how medical imaging matches and mismatches movement function of patients. Chapter 38 reflects changes in the role of PTs and OTs as they integrate more complex technologies into clinical practice.

Examination tools presented throughout the text should help the reader identify many objective measures. The reader is reminded that although a tool may be discussed in one chapter, its use may have application to many other clinical problems. Chapter 8 summarizes the majority of neurological tools available to therapists today, and the authors of each clinical chapter may discuss specific tools used to evaluate specific clinical problems and diagnostic groups. The same concept is true with regard to general treatment suggestions and problem-solving strategies used to analyze motor control impairments as presented in Chapter 9; authors of clinical chapters will focus on evidence-based treatments identified for specific patient populations.

The changing world of health care

To understand how and why disablement, enablement, and health classification models have become the accepted models used by PTs and OTs when evaluating, diagnosing, prognosing, and treating clients with body system impairments, activity limitations, and participation restrictions resulting from neurological problems, it is important for the reader to review the evolution of health care within our culture. This review begins with the allopathic medical model because this model has been the dominant model of health care in Western society and forms the conceptual basis for health care in industrialized countries.31 The allopathic model assumes that illness has an organic base that can be traced to discrete molecular elements. The origin of disease is found at the molecular level of the individual’s tissue. The first step toward alleviating the disease is to identify the pathogen that has invaded the tissue and, after proper identification, apply appropriate treatment techniques including surgery, drugs (see Chapter 36), and other proven methods.

Levin32 points out that there is a lot that consumers can do for themselves. Most people can assume responsibility to care for minor health problems. The use of nonpharmaceutical methods (e.g., hypnosis, biofeedback, meditation, and acupuncture) to control pain is becoming common practice. The recognition and value of a holistic approach to illness are receiving increasing attention in society. Treatment designed to improve both the emotional and physical needs of clients during illness has been recognized and advocated as a way to help individuals regain some control over their lives (see Chapters 5 and 6).

An approach that takes this holistic perspective centers its philosophy on the patient as an individual.33 The individual with this orientation is less likely to have the physician look only for the chemical basis of his or her difficulty and ignore the psychological factors that may be present. Similarly, the importance of focusing on an individual’s strengths while helping to eliminate body system impairments and functional limitations in spite of existing disease or pathological conditions plays a critical role in this model. This influences the roles PT and OT will play in the future of health care delivery and will continue to inspire expanded practice in these professions.

The health care delivery system in Western society is designed to serve all of its citizens. Given the variety of economic, political, cultural, and religious forces at work in American society, education of the people with regard to their health care is probably the only method that can work in the long run. With limitations placed on delivery of medical care, the client’s responsibility for health and healing is constantly increasing. The task of PTs and OTs today is to cultivate people’s sense of responsibility toward their own health and the health and well-being of the community. The consumer has to accept and play a critical role in the decision-making process within the entire health care delivery model to more thoroughly guarantee compliance with prescribed treatments and optimal outcomes.34–40 PTs and many OTs today are entering their professional careers at a doctoral level and beginning to assume the role of primary care providers. A requisite of this new responsibility is the performance of a more diligent examination and evaluation process that includes a comprehensive medical screening of each patient/client.41,42 Patient education will continue to be an effective and vital approach to client management and has the greatest potential to move health care delivery toward a concept of preventive care. The high cost of health care is a factor that will continue to drive patients and their families to increase their participation in and take responsibility for their own care.43 Reducing the cost of health care will require providers to empower patients to become active participants in preventing and reducing impairments and practicing methods to regain safe, functional, pain-free control of movement patterns for optimal quality of life.

In-depth analysis of the holistic model

Carlson44 thinks that pressure to change to holistic thinking in medicine continues as a result of a societal change in its perspective of the rights of individuals. A concern to keep the individual central in the care process will continue to grow in response to continued technological growth that threatens to dehumanize care even more. The holistic model takes into account each person’s unique psychosocial, political, economic, environmental, and spiritual needs as they affect the individual’s health.

The nation faces significant social change in the area of health care. The coming years will change access to health care for our citizens, the benefits, the reimbursement process for providers, and the delivery system. Health care providers have a major role in the success of the final product. The Pew Health Professions Commission45 identified issues that must be addressed as any new system is developed and implemented. Most, if not all, of the issues involve close interactions between the provider and client. These issues include (1) the need of the provider to stay in step with client needs; (2) the need for flexible educational structures to address a system that reassigns certain responsibilities to other personnel; (3) the need to redirect national funding priorities away from narrow, pure research access to include broader concepts of health care; (4) the licensing of health care providers; (5) the need to address the issues of minority groups; (6) the need to emphasize general care and at the same time educate specialists; (7) the issue of promoting teamwork; and (8) the need to emphasize the community as the focus of health care. There are other important issues, but the last to be included here is mentioned in more detail because of its relevance to the consumer. Without the consumer’s understanding during development of a new system, the system could omit several opportunities for enrichment of design. Without the understanding of the consumer during implementation of a new system, the consumer might block delivery systems because of lack of knowledge. Thus, the delivery of service must be client centered and client and family driven, and the focus of intervention needs to be in alignment with client objectives and desired outcomes.33–36,46,47 Today, as stated earlier,43 this need may be driven more by financial necessity than by ethical and best practice philosophy, but the end result should lead to a higher quality of life for the consumer.

Providers are more willing to include the client by designing individualized plans of care, educating, addressing issues of minority groups, and becoming proactive team caregivers.37–40 The influence of these methods extends to the community and leads to greater patient/client satisfaction. The research as of 2011 demonstrates the importance of patient participation, and this body of work is expected to grow.

The potential for OTs and PTs to become primary providers of health care in the twenty-first century is becoming a greater reality within the military system as well as in some large health maintenance organizations (HMOs).48–53 The role a therapist in the future will play as that primary provider will depend on that clinician’s ability to screen for disease and pathological conditions, examine and evaluate clinical signs that will lead to diagnoses and prognoses that fall inside and outside of the scope of practice, and select appropriate interventions that will lead to the most efficacious, cost-effective treatment.

Therapeutic model of neurological rehabilitation within the health care system

Traditional therapeutic models

Physical and occupational therapy practice models

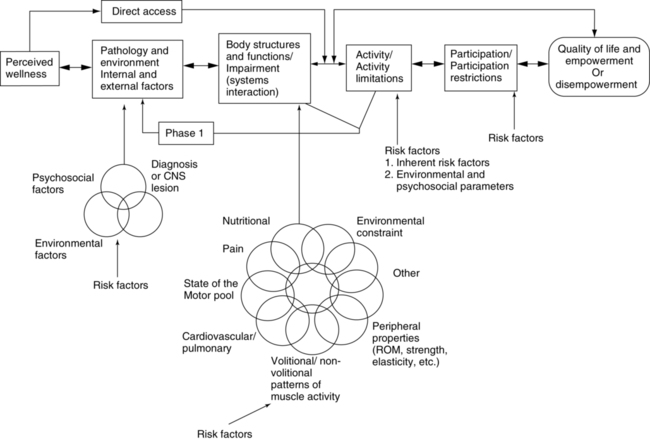

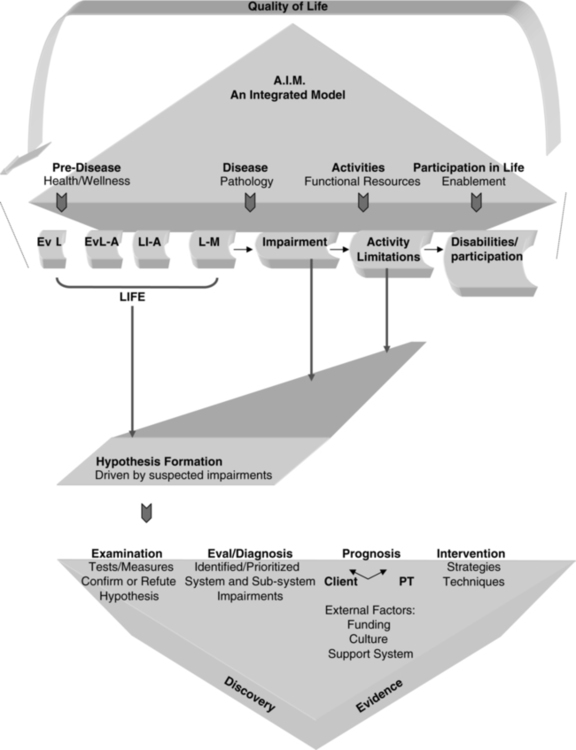

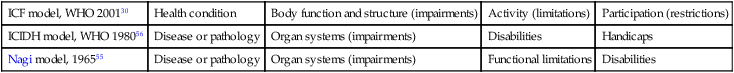

Disablement models have been used by clinicians since the 1960s. These models are the foundation for clinical outcomes assessment and create a common language for health care professionals worldwide. The first disablement model was presented in 1965 by Saad Nagi, a sociologist.54,55 The Nagi model was accepted by APTA and applied in the first Guide to Physical Therapist Practice, which was introduced in 2001.30 In 1980 the ICIDH was published by the World Health Organization (WHO).56 This model helped expand on the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), which has a narrow focus based on categorizing diseases. The ICIDH was developed to help measure the consequences of health conditions on the individual. The focus of both the Nagi and the ICIDH models was on disablement related to impaired body structures and functions, functional activities, and handicaps in society (Figure 1-1). The WHO ICF model28 evolved from a linear disablement model (Nagi, ICIDH) to a nonlinear, progressive model (ICF) that encompasses more than disease, impairments, and disablement. It includes personal and environmental factors that contribute to the health condition and well-being of individuals. The ICF model is considered an enablement model as it not only considers dysfunctions, but helps practitioners and researchers understand and use an individual’s strengths in the clinical presentation. Each of these models provides an international standard to measure health and disability, with the ICF emphasizing the social aspects of disability. The ICF recognizes disability not only as a medical or biological dysfunction, but as a result of multiple overlapping factors including the impact of the environment on the functioning of individuals and populations. The ICF model is presented in Table 1-1 and discussed in greater depth in Chapters 4, 5, and 8.

It is easy to integrate the ICF model into behavioral models for the examination, evaluation, diagnosis, prognosis, and intervention of individuals with neurological system pathologies (see Figure 1-1). Whether an individual’s activity limitations, impairments, and strengths lead to a restriction in the ability to participate in life activities, the perception of poor health, or restriction in the ability to adapt and adjust to the new health condition will determine the eventual quality of life of the person and the amount of empowerment or control he or she will have over daily life. The importance of the unique qualities of each person and the influence of the inherent environment helped to drive changes to world health models. The ICF is widely accepted and used by therapists throughout the world and is now the model for health in professional organizations such as APTA in the United States.30

As world health care continues to evolve, so will the WHO models. The sequential evolution of the three models is illustrated in Table 1-1. This evolution has created an alignment with what many therapists and master clinicians have long believed and practiced—focus on the patient, not the disease. The shift from disablement to enablement models of health care is a reflection of this change in perspective.

TABLE 1-1

ENABLEMENT AND DISABLEMENT MODELS WIDELY ACCEPTED THROUGHOUT THE WORLD OVER THE LAST 50 YEARS*

| ICF model, WHO 200130 | Health condition | Body function and structure (impairments) | Activity (limitations) | Participation (restrictions) |

| ICIDH model, WHO 198056 | Disease or pathology | Organ systems (impairments) | Disabilities | Handicaps |

| Nagi model, 196555 | Disease or pathology | Organ systems (impairments) | Functional limitations | Disabilities |

*Placed in table form to show similarities in concepts across the models. Please note that the ICF is a nonlinear, progressive model of enablement and includes contextual factors (personal and environmental) that contribute to the well-being of the individual. Also refer to Chapter 8 for a more detailed discussion of the ICF model.

Conceptual frameworks for client/provider interactions

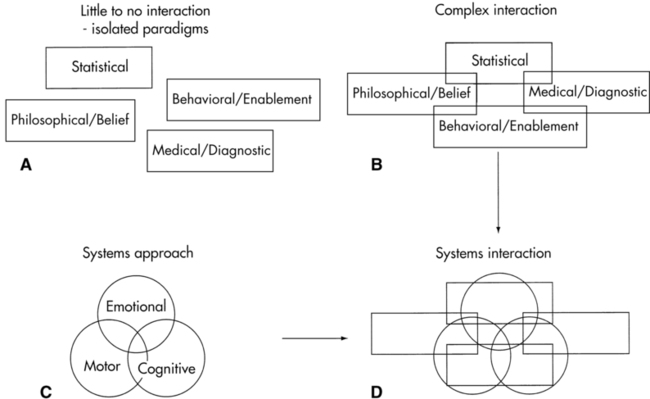

Three conceptual frameworks for client-provider interactions are commonly used in the current health care delivery system. Each framework serves a different purpose and is used according to the goals of the desired outcome and the group interpreting the results (Figure 1-2). The four primary conceptual frameworks include (1) the statistical model, (2) the medical diagnostic model, (3) the behavioral or enablement model, and (4) the philosophical or belief model.

Medical diagnostic model

Physicians are educated to use a medical disease or pathological condition diagnostic model for setting expectations of improvement or lack thereof. In patients with neurological dysfunction, physicians generally formulate their medical diagnosis on the basis of results from complex, highly technical examinations such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), computerized axial tomography (CAT or CT scan), positron emission tomography (PET scan), evoked potentials, and laboratory studies (see Chapter 37). When abnormal test results are correlated with gross clinical signs and patient history such as high blood pressure, diabetes, or head trauma, a medical diagnosis is made along with an anticipated course of recovery or disease progression. This medical diagnostic model is based on an anatomical and physiological belief of how the brain functions and may or may not correlate with the behavioral and enablement models used by therapists.

Behavioral or enablement model

The behavioral or enablement model evaluates motor performance on the basis of two types of measurement scales. One type of scale measures functional activities, which range from simple movement patterns such as rolling to complex patterns such as dressing, playing tennis, or using a word processor. These tools identify functional activities or aspects of life performance that the person has been or is able to do and serve as the “strengths” when remediating from activity limitations or participation restrictions. The second scale looks at bodily systems and subsystems and whether they are affecting functional movement. These measurement tools must look at specific components of various systems and measure impairments within those respective areas or bodily systems. For example, if the system to be assessed is biomechanical, a simple tool such as a goniometer that measures joint range of motion might be used, whereas a complex motion analysis tool might be used to look at interactions of all joints during a specific movement. These types of measurements specifically look at movement and can be analyzed from both an impairment and an ability perspective. Chapter 8 has been designed to help the reader clearly differentiate these two types of measurement tools and how they might be used in the diagnosis, prognosis, and selection of intervention strategies when analyzing movement.

Philosophical or belief model

Therapists appreciate a statistical model through research and acceptance of evidence-based practice. A third-party payer also uses numbers to justify payment for services or to set limits on what will be paid and for specific number of visits that will be covered. Therapists also appreciate physicians’ knowledge and perspective of disease and pathology because of the effect of disease and pathology on functional behavior and the ability to engage and participate in life. On the other hand, third-party payers and physicians may not be aware of the models used by OTs and PTs. It is therefore critical that therapists make the bridge to physicians and third-party payers because research has shown that interdisciplinary interactions help reduce conflict between professionals and provide better consistency for the patient.57,58

It is a medical shift in practice to recognize that patient participation plays a critical role in the delivery of health care. The importance of the patient and what each individual brings to the therapeutic environment has been recognized and incorporated into patient care by rehabilitation professionals.37–40 This integration and acceptance will guide health care practice well into the next decade.

The need for students to develop problem-solving strategies is accepted by faculty across the country and by the respective accrediting agencies of health professionals. Unfortunately, we may not be educating students to the level of critical thinking that we hope.59,60 The need for this cognitive skill development in clinicians may be emergent as both physical and occupational therapy professions have moved or plan to move to a doctoring professions.49 All health-related professions must evolve as patient care demands increase, delineation of professional boundaries become less clear, and collaboration becomes a more integral factor in providing high-quality health care.

All previously presented models (statistical, medical, behavioral, or belief) can stand alone as acceptable models for health care delivery (see Figure 1-2, A) or can interact or interconnect (Figure 1-2, B). These interconnections should validate the accuracy of the data derived from each model. The concept of an integrated problem-solving model for neurological rehabilitation must also identify the functional components within the CNS (Figure 1-2, C).

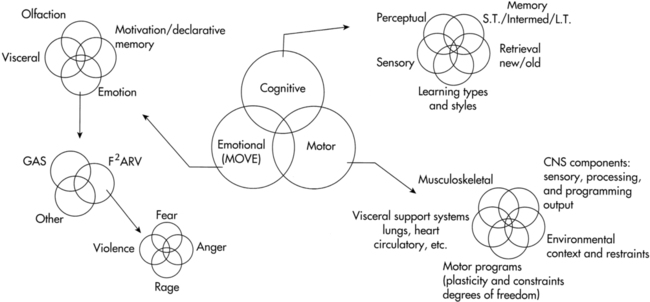

A model that identifies the three general neurological systems (cognitive, emotional, motor) found within the human nervous system can be incorporated into each of the other models separately or when they are interconnected (Figure 1-2, D). A systems or behavioral model that focuses on the neurological systems is much more than just the motor systems and their components, or cognition with its multiple cortical facets, or the affective or emotion limbic system with all its aspects. The complexity of a neurological systems model (Figure 1-3), whether used for statistics, for medical diagnosis, for behavioral or functional diagnosis, or for documentation or billing, cannot be oversimplified. As the knowledge bank regarding central and peripheral system function increases, as well as knowledge about their interactions with other functions within and outside the body, the complexity of a systems model also enlarges.61 The reader must remember that each component within the nervous system has many interlocking subcomponents and that each of those components may or may not affect movement. Therapists use these movement problems as guidelines to establish problem lists and intervention sequences. These components, considered impairments or reasons why someone has difficulty moving, are critical to therapists but are of little concern within a general statistics model and may have little bearing on the medical diagnosis made by the physician.

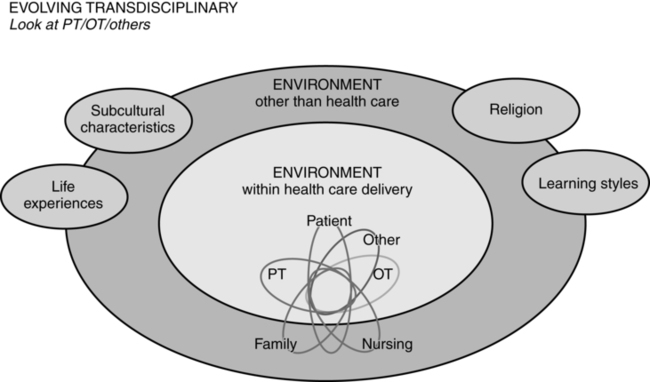

In addition to the Western health care delivery paradigms are the interlocking roles identified within an evolving transdisciplinary model (Figure 1-4). Within this model, the environments experienced by the client both within the Western health care delivery system and those environments external to that system are interlocking and forming additional system components; they influence one another and affect the ultimate outcome demonstrated by the client. Because all these once-separate worlds encroach on or overlay one another and ultimately affect the client, practitioners are now operating in a holistic environment and must become open to alternative ways of practice. Some of those alternatives will fit neatly and comfortably with Western medical philosophy and be seen as complementary. Evidence-based practice, which used linear research to establish its reliability and validity, has provided therapists with many effective tools both for assessment and treatment, but we still are unable to do similar analyses while simultaneously measuring multiple subsystem components. We can measure tools and interventions across multiple sites but are a long way from truly understanding the future of best practice. Other evaluation and treatment tools may sharply contrast with Western research practice, having too many variables or variables that cannot be measured; therefore arriving at evidence-based conclusions seems an insurmountable problem. In time many of these other assessment tools and intervention strategies may be accepted, once research methods have been developed to show evidence of efficacy, or they may be discarded for the same reason. Until these approaches have gone beyond belief in their effects, therapists will always need to expend additional focus measuring quantitative outcomes and analyzing accurately functional responses. Because the research is not available does not mean the approach has no efficacy (see Chapter 39). Thus the clinician needs to learn to be totally honest with outcomes, and quality of care and quality of life remain the primary objective for patient management. Today, models that incorporate health and wellness have been added to these disablement and enablement models to delineate the complexity of the problem-solving process used by therapists62,63 (see Chapter 2). This delineation should reflect accurate behavioral diagnoses based on functional limitations and strengths, preexisting system strengths and accommodations, and environmental-social-ethnic variables unique to the client. Similarly, it includes the family, caregiver, financial security, or health care delivery support systems. All these variables guide the direction of intervention64 (Figure 1-5). These variables will affect behavioral outcomes and need to be identified through the examination and evaluation process. Many of these variables may not relate to the CNS disease or pathological condition medical diagnosis to which the patient has been assigned.

The client brings to this environment life experiences. Many of these life events may have just been a life experience; others may have caused slight adjustments to behavior (e.g., running into a tree while skiing out of patrolled downhill ski areas and then never doing it again), some may have caused limitations (e.g., after running into the tree, the left knee needed a brace to support the instability of that knee during any strenuous exercising), or caused adjustments in motor behavior and emotional safety before that individual entered the heath care delivery system after CNS problems occurred. The accommodations or adjustments can dramatically affect both positively and negatively the course of intervention. To quickly accumulate this type of information regarding a client, the therapist must become open to the needs of the client and family. This openness is not just sensory, using eyes and ears, but holistic and includes a bond that needs to and should develop during therapy (see Chapters 5 and 6).

Efficacy

Efficacy has been defined as the “ability of an intervention to produce the desired beneficial effect in expert hands and under ideal circumstances.”65 When any model of health care delivery is considered, the question the therapist must ask is “Which model will provide the most efficacious care?” Therapists may not diagnose a pathological disease or its process, but they are in a position of responsibility to examine body systems for existing impairments and to analyze normal movement to determine appropriate interventions for activity-based functional problems. Some differences in this responsibility may exist between practice settings. Therapists in private practice act independently to select both examination tools and intervention approaches that are efficacious and prove beneficial to the patient. Within a hospital-based system, therapists may be expected to use specific tools that are considered a standard of care for that facility, regardless of the therapy diagnosis and treatment rendered. In some hospitals and rehabilitation settings a clinical pathway may be employed that defines the roles and responsibilities of each person on a multidisciplinary team of medical professionals. Regardless of which clinical setting or role the therapist plays, it is always the responsibility of the therapist to be sure that the plan of care is appropriate, is consistent with the medical and therapy diagnoses, meets the needs of the patient, and renders successful outcomes. If the needs of the particular client do not match the progression of the pathway, it is the therapist’s responsibility to recommend a change in the client’s plan of care. Efficacy does not come because one is taught that an examination tool or intervention procedure is efficacious, it comes from the judicious use of tools to establish impairments, activity limitations, and participation restrictions, identify movement diagnoses, create functional improvements, and improve quality of life in those individuals who have come to us for therapy.

Today’s health care climate demands that the therapeutic care model be efficient, be cost-effective, and result in measurable outcomes.66 The message being given today might be considered to reflect the idea that “the end justifies the means.” This premise has come to fruition through the linear thought process of established scientific research. Yet when a holistic model is accepted into practice it becomes apparent that outcome tools are not yet available to simultaneously measure the interactions of all body systems that make up the patient, making it difficult to apply models that purport to balance quality and cost of care. Thus we must guard against the reductionist research of today, which has the potential to restrain our evolution and choice of therapeutic interventions. Sometimes the individuals making decisions about what to include and what to eliminate with regard to patient services are not health care providers. They are individuals who are trained to use evidence gained from numbers or statistics to make their decision and do not have knowledge of the patient, his or her situation, or the effect of the neurological condition on function. Therapists should always be able to defend their choice and use of intervention approaches. This becomes even more relevant as the cost of health care rises.

Evidence-based practice is basic to the care process.30,67,68 Clinicians need to identify which of their therapeutic interventions have demonstrated positive outcomes for particular clinical problems or patient populations and which have not.69 Those that remain in question may still be judged as useful. The basis for that judgment may be a client satisfaction variable that has become a critical variable for many areas in health care delivery.70,71 But there is still limited information on patient satisfaction with PT and OT services, although within the last few years more information has become available.72–76 Although patient satisfaction is a critical variable within the ICF model, there are always problems with satisfaction and outcomes versus identification of specific measurable variables within the CNS that are affecting outcomes. One reason for the problem of integrating patient satisfaction with PT and OT services within a neurorehabilitation environment is the large discrepancy between the variables we can measure and the variables within the environment that are affecting performance. For example, when a neurosurgeon once asked the question to one of the editors, “Do you know how to prove the theories of intervention you are teaching?” The answer was, “Yes, all I need are two dynamic PET units that can be worn on both the client’s and the therapist’s heads while performing therapeutic interventions. I also need a computer that will simultaneously correlate all synaptic interactions between the therapist and the client to prove the therapeutic effect.” The physician said, “We don’t have those tools!” The response was, “You did not ask me if the research tools were available, only if I know how to obtain an efficacious result.” Thus, the creativity of the therapist will always bring the professions to new visions of reality. That reality, when proven to be efficacious, assists in validating the accepted interventions used by the professional. The therapist today has a responsibility to provide evidence-based practice to the scientific community…but more important, also to the client. Therapeutic discovery usually precedes validation through scientific research. This discovery leads the way to, first, effective interventions, followed by efficacious care. If research and efficacious care always have to come before the application of therapeutic procedures, nothing new will evolve because discovery of care is most often, if not always, found in the clinic during interaction with a client. Thus the range of therapeutic applications will become severely limited and the evolution of neurological care stopped if that discovery is ignored because there is no efficacy as defined by today’s research models. However, performing interventions because the approaches “have been typically done in the past” could be wasteful and irresponsible.

Diagnosis: A process used by all professionals when drawing conclusions

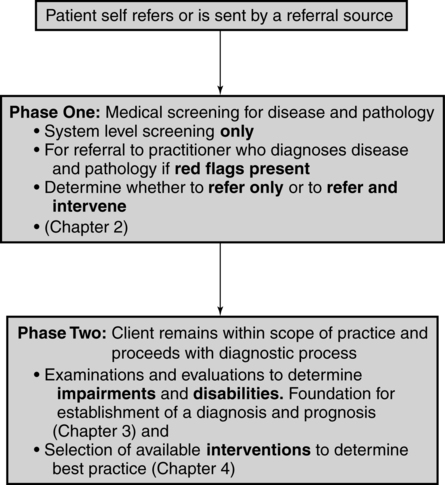

The diagnostic process used by therapists is complex and is clearly divided into two specific phases of differential diagnosis (Figure 1-6). This is further explained in Chapters 7 and 8.

Phase 1: differential diagnosis: system screening for possible disease or pathology

With the increasing use of direct access and the length of time therapists spend with clients, clinicians have become acutely aware of the need to screen systems for signs of disease and pathological conditions.51 Accreditation standards for both PTs and OTs require the new learner to develop these skills before graduation. This screening process is used to determine whether the client should be referred to another practitioner, such as a physician, or can progress to diagnosis, prognosis, and intervention within the specific discipline. Thus Phase 1 of this differential diagnosis separates a client’s clinical problems into those that fall within a therapist’s scope of practice and those that do not. If the Phase 1 differential diagnosis shows signs and symptoms totally outside a therapist’s scope of practice, then a referral to an appropriate practitioner must be made. If the signs and symptoms both fall within the clinician’s scope of practice and overlap with that of other disciplines, the therapist must refer and decide (1) to treat to prevent problems until the other practitioner’s treatment can be performed, (2) to manage the limitations in activity and participation in spite of the pathological process, or (3) to manage functional loss and impairments and therefore correct the pathological cause. In some cases the overlapping with other disciplines may not necessitate an immediate referral, but interactions must be made when needed to ensure the best outcome from intervention. However, when the information obtained by the therapist from this phase of differential diagnosis indicates a possible immediate and life-threatening condition, the therapist must act accordingly by calling 911 and referring the patient to a medical physician. Chapter 7 has been designed to help the reader grasp a better understanding of Phase 1 of differential diagnosis. This form of system screening is part of history taking and may be redone periodically throughout treatment if the therapist has questions regarding changes in body systems. In the Guide to Physical Therapist Practice30 this step is called systems review and review of systems. There may be times when the therapist has received a referral for a chronic problem and during the medical screen the patient demonstrates signs of a potential medical condition that has nothing to do with the referral. In that situation the therapist may continue with treatment but also should refer the patient back to a physician for a more thorough evaluation of the new problem.

For example, a patient was referred to a PT for treatment of chronic back pain caused by degenerative disc disease. During performance of a system screening the therapist determined that the patient had generalized weakness on the left side. On a return visit 2 days later the patient continued to demonstrate mild weakness on the left side. The therapist referred the patient back to the doctor, and the subsequent MRI showed that the woman had a large tumor in the right lower frontal-temporal lobe area. Over subsequent treatments the therapist was able to eliminate most of the chronic pain in her back. The patient to this day feels the therapist saved her life.77

Phase 2: differential diagnosis within a therapist’s scope of practice

Once the client’s signs and symptoms have been determined to fall clearly within the scope of PT and OT practice, a definitive therapy diagnosis, prognosis, and plan of care can be established. The use of an enablement model such as the ICF will help the therapist best capture the patient’s strengths, impairments, activity limitations, and participation restrictions, which can then be used to determine the patients goals, address the individual’s needs, and optimize function and quality of life (see Figure 1-1). The client’s functional goals and expectations may include activities of daily living, job skills, recreation and leisure activities, or the skills required for performance of typical societal roles. Each of these goals must have a realistic, objective, measurable outcome that is based on the results of carefully chosen examination tools. An in-depth conceptual framework for selection of appropriate examination procedures needed to evaluate and draw appropriate diagnostic conclusions can be found in Chapter 8.

Two important clinical components affect the accuracy of the diagnostic conclusion. First, the clinician must establish accurate, nonbiased results. This fact seems obvious, but with the pressures of third-party payers, family members, other care providers, and the desire to have the client improve, it is easy to submit to drawing a conclusion based on desired outcomes rather than facing what is truly present and realistic. The second factor deals with the honesty of the interaction between the therapist and the client. This “bonding” is critical for obtaining accurate examination results. Safety, trust, and acceptance of the client as a human being play key roles in therapeutic outcomes and thus in efficacy of practice.78–81 The reader is referred to Chapters 5 and 6 to develop a greater understanding of the impact this bonding has on clinical outcomes.

Prognosis: how long will it take to get from point A to point B?

If a client has a variety of impairments, activity limitations, and participation restrictions, then a variety of appropriate prognoses may be formulated. These prognoses could be used to speculate the amount of time or number of treatments it will take to get from the existing activity limitations and participation restrictions (point A) to the desired outcomes (point B). The outcomes will state whether the intervention will (1) eliminate functional limitations through changes, adaptations, and learning within the client as an organism or (2) improve function through compensation and modification of the external environment. Once the therapy diagnosis has been established, a clinician must consider many factors when making a prognosis. Some factors are related to the internal environment of the client, such as number and extent of impairments, level of physical conditioning or deconditioning of the client, the ability and motivation to learn, participate, and change, and the neurological disease or condition that led to the existing problems. The client’s support systems have a dramatic impact on prognosis. Cultural and ethnic pressures, financial support to promote independence, availability of appropriate skilled professional services, prescribed medications, and the interaction of all of these factors need to be considered. Specific environmental factors such as belief in health care and agreement about who has the responsibility for healing can create tremendous conflict among current health care delivery systems; the client; the family; and you, the clinician.79,82,83 All of these variables affect prognosis. The last aspect of determining prognosis relates to empowerment of the client. Who sets the goals? Who determines function? Who identifies when a therapeutic modality should be used versus a meaningful life activity? If consensus to these questions cannot be found by the therapist and the client, then conflict between anticipated and actual outcome will result and a definitive prognosis will not be achieved.

Once a prognosis has been established, the therapist’s next step is to identify the intervention strategies that will guide the client to the desired outcome within the time frame identified. (Refer to Chapter 9 and all chapters in Section II.)

Documentation

Documentation of the examination, evaluation, goals, plan, and daily interventions has always been integral to the therapeutic process. However, there is added emphasis in today’s health care environment, as well as a renewed respect for the importance of the issue. Documentation must produce a clear framework from which to record and follow client progress. Documentation communicates the process of care and the product or outcome of that process. The outcome is the realistic reflection of the effectiveness of care. The goals should be stated in measurable functional terms and prioritized in order of importance to the client. The number of goals developed by the therapist takes into account the realistic probability of effectiveness of interventions, the environment in which the interventions will likely occur, and support systems available to the client. As the process goes forward, the therapist may add, delete, or change a functional goal, and so states that on the client’s record. Refer to Chapter 10 for further information about this process.

Intervention

Clients with neurological diseases or conditions can interact with the medical community for either short or long periods. They possess neurological problems of all types that range from sudden to insidious in onset and presentation. All aspects of human function are represented in the variety of problems. If individual beliefs and values energize and motivate physical behavior, think of the possibilities for stimulating wellness. Return to wellness might be considered return to previous function, maintenance of function, slowing progression of functional loss, habilitation of function never achieved, and striving for excellence in performance. Refer to Chapter 9 for additional discussion.

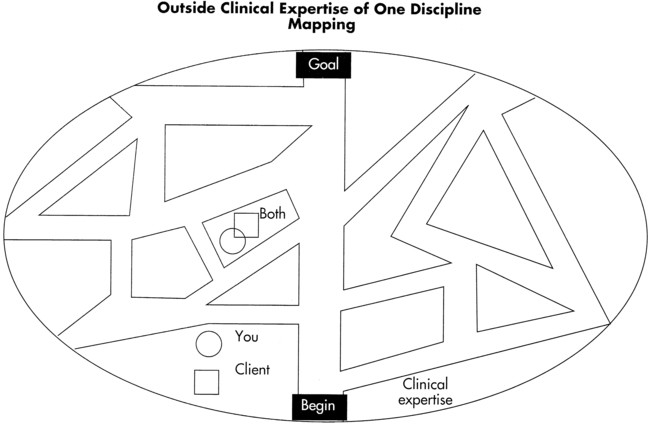

The established plan of care determines the interventions and the method, or road map, toward the achievement of the agreed-on outcome goals. The therapist, in collaboration with the client, can choose from restrictive and nonrestrictive treatment environments and interventions to best achieve identified goals. The available choices of interventions will depend on the therapist’s skill, the level of function and ability of the client to control his or her own neuromuscular system, and treatment tools and strategies that are available in the clinic. Yet freedom within that established environment must exist if learning by the client is to occur. Another way to consider intervention is to refer to it as a clinical road map (Figure 1-7). Within the map, a therapist, through professional education, efficacy of preexisting clinical pathways, and clinical experience can generally identify the most expedient way to guide a client toward the desired outcome. When the specific client enters into this interaction, slight variations off the existing pathway may lead to quicker outcomes. If the client diverges away from the desired end product, it is the therapist’s responsibility to guide that individual back into the clinical map. For example, if a therapist and client are working on coming to standing patterns and the client begins to fall, the therapist would need to guide the client back into the desired movement patterns and not allow the fall. In that way the client is working on the identified outcome. Falling as a functional activity should be taught as a different intervention and would be considered part of a different clinical map. The degree to which the therapist needs to control the response of the client will determine the extent to which the intervention would be considered contrived. Contrived interventions can, in time, lead to functional independence of the client, but as long as the therapist needs to control the environment, functional independence has not been achieved. There are many ways to get to a desired outcome. Involving the client in the goal setting and intervention planning process will lead to the best result These interactions require trust of the therapist as a guide and teacher. Refer to Chapter 9 and all chapters in Section II for a more thorough discussion of intervention strategies.

Concept of clinical mapping.

Concept of clinical mapping.Most treatment interventions used for clients with CNS pathology incorporate principles of neuroplasticity, adaptation, motor control, and motor learning in various environmental contexts. Thus, the consideration of the basic science of central and peripheral nervous system function (see Chapter 4) and a behavioral analysis of movement (see Chapter 3) must be included in any conceptual model used as a foundation for the entire diagnostic process.

Concept of human movement as a range of observable behaviors

Two important aspects of the clinical problem-solving process emerge when observing motor behavior. First, the evaluation of motor function is based on the interaction of all components of the motor system and the cognitive and affective influences over this motor system, as stated previously. Second, the therapist needs to recognize which aspects of the movement are deficient, absent, distorted, or inappropriate when cross-referenced with the desired outcome (part of the diagnosis-prognosis process). These behaviors, although dependent on many factors, are consistent regardless of age of the client. Some clients may not have had the opportunity to experience the desired skill, whereas others may have lost the skill as a result of changes within the CNS or disuse. In either case, the normal accepted patterns and range of behaviors remain the same. Refer to Chapter 3 for an additional discussion of movement analysis across the life span.

The complexity of the central nervous system as a control center

The concept of the CNS as a control center is based on a therapist’s observations and understanding of the sensory-motor performance patterns reflective of that system. This understanding requires an in-depth background in neuroanatomy, neurophysiology, motor control, motor learning, and neuroplasticity and gives the therapist the basis for clinical application and treatment. Understanding the intricacies and complex relationships of these neuromechanisms provides therapists with direction as to when, why, and in what order to use clinical treatment techniques. Motor behaviors emerge based on maturation, potential, and degeneration of the CNS. Each behavior observed, sequenced, and integrated as a treatment protocol should be interpreted according to neurophysiological and neuroanatomical principles as well as the principles of learning and neuroplasticity. As science moves toward a greater understanding of the neuromechanisms by which behaviors occur, therapists will be in a better position to establish efficacy of intervention. Unfortunately, our knowledge of behavior is ahead of our understanding of the intricate mechanisms of the CNS that create it. Thus the future will continue to expand the reliability and validity of therapeutic interventions designed to modify functional movement patterns. First, therapists need to determine what interventions are effective within a clinical environment. Then the efficacy of specific treatment variables can be studied and more clearly identified. The rationale for the use of certain treatment techniques will likely change over time. As our knowledge of the CNS continues to evolve, so will the validation of techniques and approaches used in therapeutic environments. At that point, evidence-based practice will truly be a reality. Chapters 4 and 5 have additional information and references on CNS function. Chapter 9 has an in-depth discussion of intervention options.

Concept of the learning environment

Understand the learning process and provide an environment that promotes learning.

Understand the learning process and provide an environment that promotes learning.

Investigate the use of sensory input and motor output systems, feed-forward and feedback mechanisms, and cognitive processing as means for higher-order learning.

Investigate the use of sensory input and motor output systems, feed-forward and feedback mechanisms, and cognitive processing as means for higher-order learning.

Use the principles and theories of motor control, motor learning, and neuroplasticity to facilitate learning and carryover of treatment into real-life environments.

Use the principles and theories of motor control, motor learning, and neuroplasticity to facilitate learning and carryover of treatment into real-life environments.

Obtain knowledge of both the client’s and the provider’s learning styles. If these learning styles are not compatible, then the clinician is obligated to teach using the client’s preferred style.

Obtain knowledge of both the client’s and the provider’s learning styles. If these learning styles are not compatible, then the clinician is obligated to teach using the client’s preferred style.

Attend to the sensory-motor, cognitive, and affective aspects of each client, regardless of the clinical emphasis at any given time.

Attend to the sensory-motor, cognitive, and affective aspects of each client, regardless of the clinical emphasis at any given time.

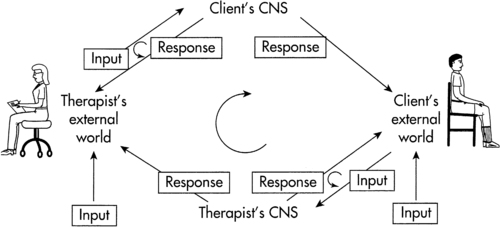

At all times there are four distinct components of the learning environment in operation: the internal and external environments of the client, and the internal and external environments of the clinician (Figure 1-8). All four represent interactive components of the learning environment.

Clinical learning environment.

Clinical learning environment.The client

A critical component of the ability to learn is the client’s internal environment. When a lesion occurs within a body system it affects the entire internal environment of the client both directly and indirectly. If the lesion occurs before initial learning, then habilitation must take place. These clients may possess a genetic predisposition for a specific learning style, even though one has not yet been established. The therapist should test the inexperienced CNS by creating experiences in various contexts that require a variety of types of higher-order processing to discover optimal methods of learning that best suit the CNS of the client. Then the therapist can employ the most effective strategies in treatment. If previous learning has occurred and preferential modes of operating have been established, then the therapist needs to know what those are and whether they have been affected by the neurological insult so that proper rehabilitation can be instituted.84 The use of preferential sensory input modes such as visual compared with verbal or kinesthetic does not mean that other modes are ineffective, nor do all modes function optimally in any given situation.

The client’s external environment is the second critical component.85 All external stimuli, including noise, lighting, temperature, touch, humidity, and smell, modulate the client’s responses. External inputs can invoke either negative or positive influences on internal mechanisms and alter the client’s ability to manipulate the world. A therapist should make every effort to be aware of what externally is influencing the client.86–89 It is important to know what is happening to the client both within and outside of the hospital or clinic experience. Any behavioral change displayed by the client, such as a change in mood or attitude, or a change in muscle tone could serve as an indicator to the therapist that an environmental effect may have occurred. A follow-up determination of what may have happened can help the therapist understand the situation, help the client deal with the environmental influences, and allow the therapist to obtain additional professional assistance if needed.

The third critical component is the internal environment of the clinician.90 The clinician should be aware of personal internal factors that can influence patient responses. Everyone has preferential styles of teaching and learning; yet many of us may be unaware of what they are and how they affect our outlook on life and interactions with other people. A common example of a mismatch of styles is what happens when two people are arguing opposing sides of a political issue. Although both individuals may process the same data, they may have different learning strategies and come up with very different conclusions.

This external-internal environmental interaction concept brings up another important clinical consideration.91 As students, most of us probably “clashed” with one or two teachers with whose learning styles we could never identify. As learners we cannot or will not adapt to all learning styles. For that reason there may be some clients who do not respond to our teaching. When that seems evident, a shift of therapists is appropriate for the rehabilitation process to succeed.

The fourth component of the learning environment is the clinician’s external environment. It is generally expected that personal life should never affect professional work. To accept this assumption, however, may be to deny that emotions affect behavioral patterns (see Chapters 5 and 6 ). Response patterns can vary without cognitive awareness when an individual is emotionally upset or under stress. For example, suppose that Mr. Smith, who has a hypertonic condition because of a stroke, comes down early for therapy each morning, has a cup of coffee, and chats while you write notes. If one day you are under extreme stress and do not feel like interacting as Mr. Smith rolls his wheelchair into your office, you might say, “Mr. Smith, I’ll be with you in a few minutes. Go over to the mat, lock your brakes, pick up the pedals, and we’ll transfer when I get there.” Mr. Smith will quickly sense a change in your behavior. Society has taught him that you are a professional and that your personal life does not affect your job. Thus he may draw a logical conclusion that he must have done something to change your behavior. When you go to transfer him you notice he is more hypertonic than usual and ask, “Is something bothering you? You’re tighter than usual,” and so goes the interaction. Your external environment altered your internal state and, thus, normal response patterns. In turn, you altered Mr. Smith’s external environment, changing his internal balance, and created a change of emotional tone that resulted in increased hypertonicity.92,93 If instead of interacting with Mr. Smith as if nothing were wrong, you had informed him you were upset over something unrelated to him, you might have avoided creating a negative environment. Mr. Smith’s responses may have been different if you had shared with him the fact that there are days that you are upset and have mood changes. As he accepts your changes as normal, you may have created an opportunity for him to also exhibit a range of behavioral moods. You have also given him an opportunity to offer his assistance to comfort or help you if he so desires. Such behavior encourages interdependence and social interaction and facilitates long-term goals for all rehabilitation clients.

Each client is unique. Therefore it is difficult to analyze the specifics related to each individual’s learning environment. However, six basic learning principles have been established that are relevant to both the client and the clinician in any learning environment.94–96 These six principles of the learning experience are as follows:

1. Individuals need to be able to solve problems and practice those solutions as motor programs if independence in daily living is desired. This requires the use of intrinsic feedback systems to modulate feed-forward motor plans as well as correct existing plans.

2. The possibility of success must exist in all functional tasks, regardless of the level of challenge to the client.

3. An individual will revert to safer or more familiar motor programs or ways to solve problems and succeed at functional tasks when task demands are new, difficult, or unfamiliar.

4. The learning effect occurs in multiple areas of the CNS simultaneously when teaching and learning are focused within one area of the CNS.

5. Motivation is necessary to drive the individual to try to experience what would be considered unknown. Simultaneously, success at the activity is critical to keep the individual motivated to continue to practice.

6. Clinicians need to be able to analyze an activity as a whole, determine its component parts, and use problem-solving strategies to design effective individualized treatment programs. At the same time, if independence in living skills is an objective, the therapist needs to teach the client those problem-solving strategies rather than teaching the solution to the problem.

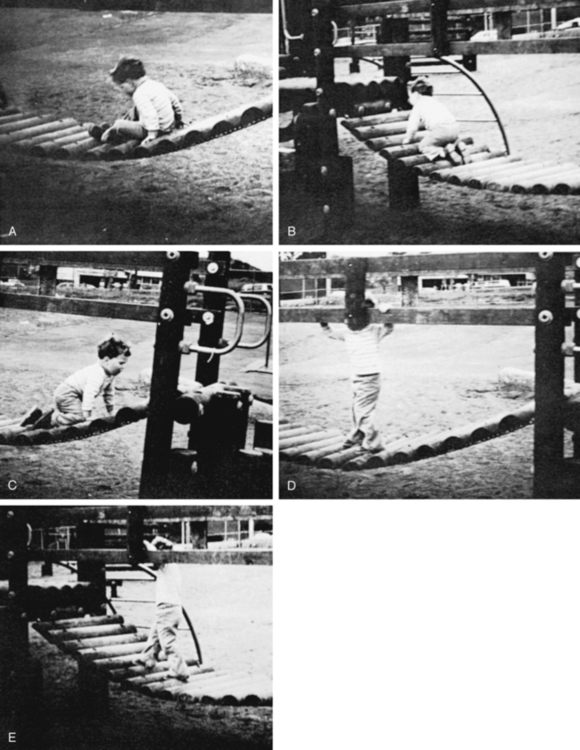

The third learning principle describes a behavior inherent in all people: reversal. When confronted by a problem, individuals revert to patterns that produce feelings of comfort and competence when solving the problem. In Figure 1-9, a 2-year-old child is confronted with just such a conflict. The bridge he wants to cross is unstable. The task goal is to cross the bridge; how that is accomplished is not as relevant as the task specificity. Therefore the child chooses a 6-month-old behavior and thus scoots. On gaining confidence, the child sequences from scooting to four-point bunny hopping, then creeping, on to cruising, and finally to reciprocal walking. The child’s reversal lasted approximately 2 minutes. Although reverting to more familiar or comfortable ways of solving problems is normal, it creates constant frustration in the clinic if it is prolonged. For example, if a client with residual hemiplegia has spent a week modifying and controlling a hypertonic upper-extremity pattern during a simple task and is now confronted with a more difficult problem, the hypertonia within the limb will most likely return with the added complexity of the task. If another client has successfully worked to obtain the standing position and then is asked to walk, the strong synergistic patterns that had been controlled may return. The pattern or plan for standing is different from that for walking, and the emotional implications of walking are very high. The clinician should anticipate the possibility of the patient returning to a more stereotypical pattern. This possibility must also be explained to the patient. Anticipating that less efficient patterns will usually return as the tasks demanded increase in complexity, the clinician can attempt to modify the unwanted responses and let the patient know that the response is actually normal given the CNS dysfunction, but that movement can be changed and normalized with practice. The key to comprehension of this concept is not the behavior itself; instead, it is the attitude of a therapist toward a new task presented to the client. If the clinician expects the client to be successful, the client will also expect success. If failure occurs, both parties will be disappointed and a potentially negative clinical situation will be created; however, if the client succeeds, both will have expected the result and their attitude will be neither excited nor depressed. On the other hand, a clinician who expects the client to revert to an old behavior can prepare the client. If the client reverts, neither party will be disappointed; but if no reversion occurs, both will be excited, pleased, and encouraged by the higher functional skill. By understanding the concept, the clinician can maintain a very positive clinical environment without the constant negative interference of perceived failure when a client does revert.

Many additional learning principles from the fields of education, development, and psychology can be used to explain the behavioral responses seen in our clients. It is not expected that all therapists will intuitively or automatically know how to create an environment conducive to helping the patient achieve optimal potential. Yet all can become better at creating a beneficial learning environment by understanding how people learn. The critical importance of being honest and accurate with prognosis and how that will ultimately affect function outcomes, participation in life, and quality of life cannot be overemphasized.97

The principles presented in this chapter deliver a strong message: individuals need to solve problems and most want to solve the problem given a chance that the solution will be successful. Unless the task fits the individual’s current capability, adaptation using whatever is available will become the consensus that drives the motor performance through the CNS. Learning is taking place in all aspects of life, and the client must ultimately take responsibility for the means to solve the problem.98

The client and provider relationship

The client’s role in the relationship

Active participation in life and in relationships promotes learning. Rogers99 defines significant learning as learning that makes a difference and affects all parts of a person. We have spoken of a relationship centered on an individual’s health. One of the individuals involved in the relationship (the therapist) has knowledge that is to be imparted to or skills to be practiced by the other. The relationship “works” if the learning environment facilitates exchange between the participants. The concept of equal partners is crucial. The issue and practice of informed consent is not just political or ethical; it is central to client care. Voluntarism has to be practiced by both practitioner and client. Each has a moral obligation to facilitate the process of health care within the moment. Although the Western world of medicine has steadily climbed a path toward excellence in medical technology and clarification of medical diagnosis as seen in WHO’s ICD-10,100 it has not as easily recognized the client’s need to assume an equal role in the decision making or for the practitioner to seek the client’s help. Consumers are now seeking to play a more active role in their health care. This role has developed out of our scientific understanding of motor learning (see Chapter 4) and the fiscal necessity of decreasing the number of therapeutic visits.

Consumers of health care are becoming aware of the affect of medicine’s control over their lives. This awareness has been fueled by the price they are paying for that health care. A recent Surgeon General’s report confirms that expenditures for health are increasing. In addition, preventive care assumes major importance in view of the fact that seven out of 10 deaths in the United States today are the result of degenerative diseases, such as heart disease, stroke, and cancer.101 Like other major causes of death, trauma (cited as the most frequent cause of death in persons younger than age 40 years102) is increasingly linked to lifestyles.

The major purpose of the patient’s relationship with the health care professional is to exchange information useful to both regarding the health care of the client. McNerney31 calls health education of the client the missing link in health care delivery. As the gap grows between technology and the users of that technology, client health education becomes more important than ever.103 McNerney31 notes that although health care providers are now making efforts to educate their clients, they are doing so with little consistency, enthusiasm, theoretical base, or imagination and often with little coordination with other services. The health care professional continues to receive training and embrace professional organizational membership that places a premium on control of information and control of the decision making. There is and should be a special effort to introduce health education concepts into the basic educational programs of health care professionals. McNerney identified many of the problems three decades ago, and many still exist today.

When patients are given more information about their illnesses and retain the information, they express more satisfaction with their caregivers. A study by Bertakis104 tested the hypothesis that patients with greater understanding and retention of the information given by the physician would be more satisfied with the physician-patient relationship. The experimental group received feedback and retained 83.5% of the information given to them by the physician. The control group received no feedback and retained 60.5% of the information. Not surprisingly, the experimental group was more satisfied with the physician-patient relationship.

The more the professional sees himself or herself as the expert, the less likely he or she will be to see the client as capable of responsibility or expertise in the care process. If communication skills and health education were an integral part of medical school and health care professional school curricula, perhaps the health care professionals would temper their assumption of the “expert” professional role. Payton105 points out that it is the client alone who can ultimately decide whether a goal is worth working for. Careful planning can be influential in helping all providers include the client in the process.

The health care delivery system in the United States has to serve all citizens.106 That is no easy task. The United States is a society of great pluralism. It is a free society. It is a society that is used to being governed by persuasion, not coercion. Given the variety of economic, political, cultural, and religious forces at work in American society, education of the people with regard to their health care is probably the only method that can work in the long run. The future task of health education will be to “cultivate people’s sense of responsibility toward their own health and that of the community.” Health education is an effective approach with perhaps the most potential to move us toward a concept of preventive care.

Becker and Maiman107 discussed Rosenstock’s Health Belief model as a framework to account for the individual’s decision to use preventive services or engage in preventive health behavior. Action taken by the individual, according to the model, depends on the individual’s perceived susceptibility to the illness, his or her perception of the severity of the illness, the benefits to be gained from taking action, and a “cue” of some sort that triggers action. The cue could be advice from a friend, reading an article about the illness, a television commercial, and so on. In some way, the person is motivated to do something.

Mass media has promoted individuals’ education, which may correctly guide or misguide consumers’ decision making.108,109 This concept was put forward as early as 1976.110 Today the consumer thus has a heightened expectation of the quality of care he or she will receive. Similarly, consumers come to receive medical care because of media education, whereas in the past that level of education was not available.111,112 As of today, the media are just beginning to be used by OT and PT professions, in the hope that this media use will educate the public regarding when, where, and how to decide on whether to seek our services. It will be a few years before research can be done to determine if this use of media will assist in educating the public.

Many aspects of today’s lifestyles do not reinforce wellness. The obesity seen throughout the industrialized world proves that point.113–115 Yet whether the client takes some responsibility for his or her functional problems and recovery depends a great deal on whether the health care provider gives some to him or her. Today’s literature certainly reinforces the need for patient responsibility and active participation in one’s own functional recovery.116–124 This change in responsibility may be caused by third-party payers and the lack of funding versus promotion of a new health care model in which the patient is an active participant, but as long as the change occurs, the world will be better served.

Fink125 in 1980, over three decades ago, recognized the importance of the provider-patient relationship. The state of what is referred to as health varies for each client and includes both the simple and complex variables of that client’s life, from the last nutritional meal to the totality of the client’s life event history (see Figure 1-5). The relationship of the therapist and the client can lead to better use of the health care system by giving responsibility to the consumer.126,127 The therapist has an advantage over most other health care practitioners, who see the patient at infrequent intervals and who seldom touch the patient as a PT or an OT does.

The illness or trauma of the client that represents a disintegrating force in his or her life may represent an opportunity for the therapist to grow professionally. The client and the therapist may have different psychological backgrounds, and, although the client’s presence is usually related to a medical crisis, the therapist’s presence may support the purposes of personal growth, financial gain, prestige, and unconscious gratification in influencing the lives of others through professional skill.128

As the consumer becomes more involved, so should the family.129 Patients in therapy have always been happier with the family involved.130 The therapist must be willing to facilitate the involvement of the family members and help them learn to take responsibility for some of the care and decision making. Most health care professionals are not conditioned to allowing patients and family members to assume responsibility for their own care; however, better outcomes can be achieved if this is permitted and accepted.

Therapists are caught up in the same problems of the health care system as other health care professionals. Inflation has often caused profit to become a more important motive than human care considerations for setting priorities in our clinics. Research is heavily focused on technical procedures, yet the relationship with patients in the care process is vital. Singleton131 labeled this phenomenon a paradox in therapy. Despite the commitment to humanistic service on which the profession was founded, the service rendered is often mechanistic.

The educational programs should emphasize whole-patient treatment, increased communication skills, interdisciplinary awareness, and patient-centered care.44–46,132 The change in roles described previously requires a professional who demonstrates a potential for the assumption of many roles, responsibilities, and choices along the care pathway. The therapist working with the client with neurological problems must always be ready to respond to triggers anywhere along the pathway from early intervention, midway during a crisis, or later during long-term care, because these triggers signal a need for change. Of equal importance, the path must be well documented to empower the therapist to reflect on current and prognosticated treatment intervention.

The provider’s role in the relationship

Gifted therapists are often thought to have intuition. Yet intuitive behavior is based on experience, a thorough knowledge of the area, sensitivity to the total environment, and ability to ask pertinent questions as the therapist evaluates, conceptualizes about, and treats clients (Chapter 5). How these questions are formulated and the answers documented vary among therapists, but the result is the formulation of a unique profile for each client.

Cognitive-perceptual processing by the client will often determine the learning environment to be used, the sequences for treatment, and the estimated time needed for therapeutic intervention. Thus the client is in a position to play an important role with the therapist within the clinical problem-solving process. In that interactive environment, the therapist can ask questions regarding cognitive, affective, and motor domains that will help clarify, document, and guide future decisions regarding empowerment of the client. (See the client profile questions regarding cognitive, affective, and sensorimotor areas in Boxes 1-1,1-2, and1-3.) The motor output area is the main system the client uses to express thoughts and feelings and demonstrate independence to family, therapists, and community. This motor area cannot be evaluated effectively by itself while the cognitive-perceptual and the affective-emotional areas are negated. If that rigidity becomes a standard of care, accurate prognosis and selection of appropriate interventions will continue to be inconsistent and lack effectiveness within the clinical environment. No one will question that therapists today need to use reliable and valid examination tools in order to measure efficacy of our interventions. Finding the link between structured examination and intuitive knowledge is a characteristic of master clinicians. Even therapists who intuitively know a patient’s problem need to use objective measures today to verify that intuition. Therefore third-party payers can justify payment for services while the patient benefits from the intuitive guidance in the clinical decision making by the therapist.