CHAPTER 10 Foundation facelift

History

Foundation facelift, formerly known as deep-plane lift, is characterized by elevation of a composite musculo-cutaneous flap of facial and upper cervical soft tissues. As the flap is rotated to a more lateral and cephalad position, it dramatically corrects tissue laxity, and rejuvenates the face. The foundation facelift is particularly effective in softening the nasolabial fold. The thickness and excellent vascularity of the flap produce long-lasting and natural results.

Patient evaluation

Foundation facelift is particularly useful in certain classes of patients.

• Patients who have had a previous SMAS-platysma operation and in whom the remaining SMAS-platysma may be insubstantial and/or scarred can still have a robust flap when the subcutaneous tissues and skin remain integrated with the SMAS-platysma as in the foundation facelift.

• Because the foundation facelift flap has a particularly strong blood supply, typical of musculo-cutaneous flaps, this operation is a good choice for smokers and other patients in whom the vascularity of the facelift flap may be suboptimal.

• The dissection plane deep to the SMAS-platysma is an avascular plane, and operations in this plane are bloodless, rarely eventuating in hematomas. The foundation lift, then, is a good choice for patients at increased risk for postoperative bleeding.

• Because the foundation facelift flap is thick and has a robust blood supply, it can be elevated to the nasolabial fold and even on to the lip without fear of flap necrosis, even when the flap is pulled up under some tension. This operation, is a champion technique for flattening deep nasolabial folds.

• Evaluate the skin of the face and neck and underlying soft tissues for laxity and loss of elasticity. Laxity is characterized by excess and redundant skin. Loss of elasticity means that the skin does not easily snap back after being put under stretch, and mitigates against a superior and long-lasting result. These patients should be warned that an early secondary operation may be necessary.

• Severe sun damage, as evidenced by rhytids, thinning of the skin, and pigmentary changes, should also be noted and pointed out to the patient. These actinic changes are little improved by facelifting, and the patient should be aware of the limitations imposed by solar damage to the skin.

• Ptosis of the platysma, evidenced by vertical bands in the anterior neck, will almost always require anterior platysma plication for correction.

• Note presence of excess fat in the neck, as removal of this excess is a sine qua non for creating a youthful neck and jaw line.

• Jowling and deep nasolabial folds should be noted. These hallmarks of facial aging are well-treated with foundation facelift.

• Descent of the malar fat pad is also a cardinal sign of aging. Its correction requires movement of the fat pad and skin in a vertical, cephalic direction.

• The quality and thickness of the preauricular skin and the presence of fine hairs on the skin should be noted in women and men. Thick, hair-bearing skin in either sex is a relative contraindication to using a retrotragal incision, since transposing the thickened, hair-bearing skin to cover the tragus will obscure the fine detail of this important anatomic landmark.

Anatomy

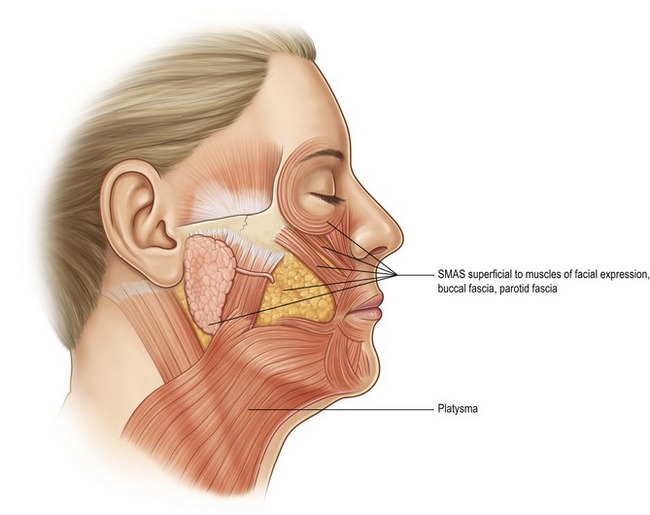

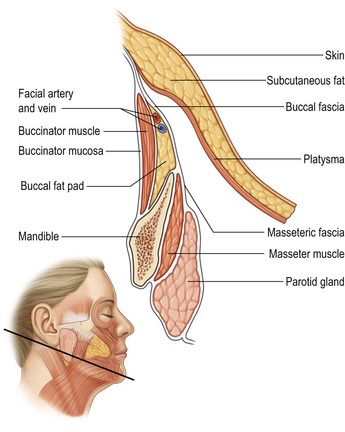

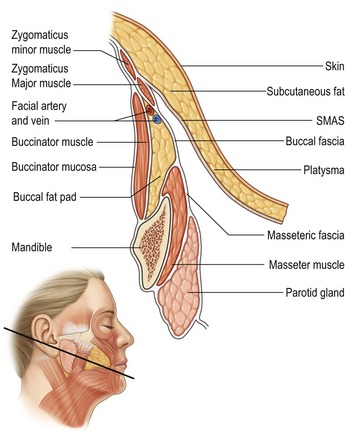

From its origin in the lower neck, the platysma muscle extends to the lower cheek, covering a portion of the lower parotid gland before inserting into the perioral muscles at the corner of the mouth (Fig. 10.1). The investing fascia of the platysma continues cephalad in the cheek as the SMAS (superficial musculo-aponeurotic system). The SMAS lies superficial to the masseter muscle and the buccal fat pad, before continuing in a cephalic direction to invest the deep and superficial layers of the zygomatic major and minor.

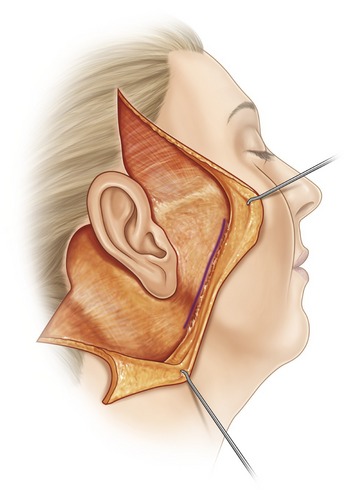

The defining feature of the foundation facelift is elevation of the SMAS-platysma, subcutaneous fat, and overlying skin as a unified flap. The SMAS-platysma is the integrated foundation of this musculo-cutaneous, composite flap. In the upper neck and lower cheek, the platysma is the deepest layer of the flap (Fig. 10.2); in the mid and upper cheek, the platysma continues as the SMAS and forms the deepest layer of the flap (Fig. 10.3).

As the nerve branches exit the parotid gland, they lie deep to two important fascial planes:

• The more superficial and thicker plane is the SMAS-platysma.

• Just deep to the SMAS-platysma is a thin layer of fascia lying just superficial to the nerve branches.

• As the zygomatic and buccal branches course in a cephalad direction, they are covered by the zygomaticus major and minor muscles (Figs 10.3 and 10.4).

• A more complete understanding of the anatomy of the foundation facelift is obtained by studying an artist’s representation of the surgeon’s view when the flap is elevated (Fig. 10.5). The platysma is elevated with the subcutaneous fat and skin in the lower cheek. In the mid and upper cheek, the platysma becomes the SMAS and is also elevated with the subcutaneous fat and skin. The malar fat pad in the upper cheek also remains attached to the skin and is elevated as the skin is mobilized and repositioned. Note the course of the branches of the facial nerve as they exit the anterior border of the parotid gland, but remain covered by masseteric fascia, buccal fascia, and the zygomaticus major.

Technical steps

Marking the patient

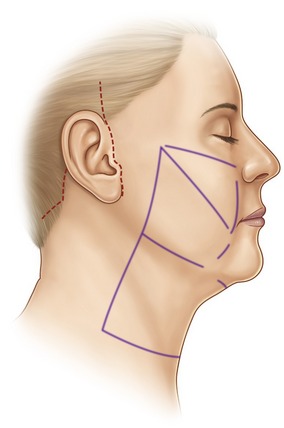

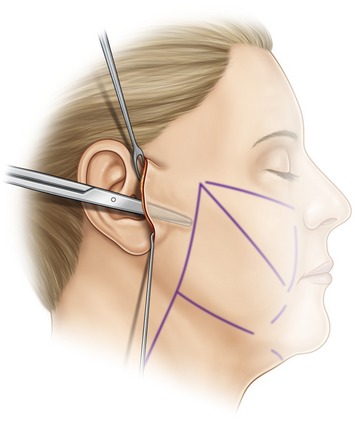

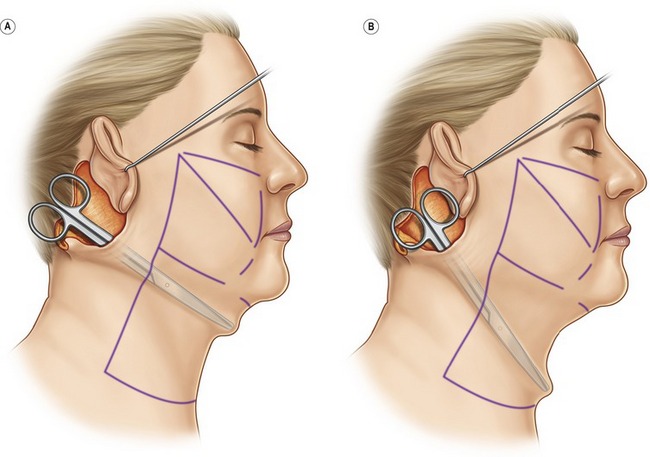

Prior to surgery, anatomic landmarks are drawn on the face and neck with the patient standing (Fig. 10.6). The drawn lines indicate:

• the point of origin and course of zygomaticus major and minor;

• the nasolabial and labiomental creases;

• the anterior border of parotid gland;

• the lateral border of platysma in neck which, for most patients, is aligned with the anterior border of the parotid;

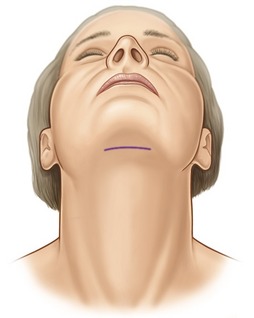

The line of the submental incision is also marked preoperatively with the patient standing so the surgeon can plan the incision in the least visible area (Fig. 10.7).

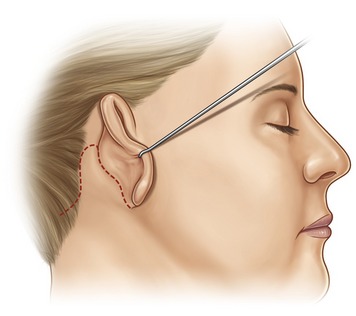

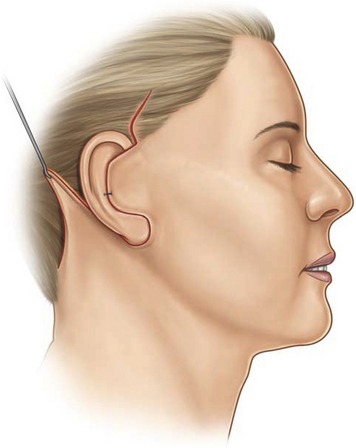

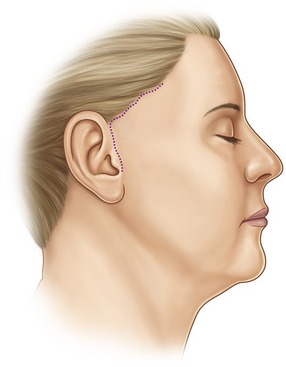

The remainder of the incision lines is drawn after intubation. The periauricular incision starts in the temporal area (Fig. 10.6). A vertical incision extending three or four centimeters into the hairline cephalad to the roll of the helix is used when access is required to the temporal area for a temporal and/or brow lift. The incision continues caudad along the helical roll to the tragus where, for most patients, it follows the edge of the tragus, and then continues along the prelobular crease (Fig. 10.6) before coming around the lobule to the retroauricular crease (Fig. 10.8). The incision follows the course of the retroauricular crease cephalad before traversing the retroauricular skin and then proceeding along the occipital hairline for three centimeters after which it turns posterior into the occipital hair.

When a temporal and/or browlift is not performed, the incision starts as a horizontal line extending from the point at which the helical rim joins the face to the anterior portion of the temporal hairline (Fig. 10.9). This incision can be extended vertically along the temporal hairline to take out excess skin. A pretragal incision is used when the preauricular skin is excessively thick and would blunt fine tragal detail if used to cover the tragus.

Fig. 10.9 Dotted lines indicate alternative incisions at temporal hairline and in preauricular crease.

Lastly, if there is little excess skin in the neck, the postauricular incision can be limited to the retroauricular crease (Fig. 10.10).

Operation

The head and neck are prepped with sterile povidone-iodine solution prior to draping.

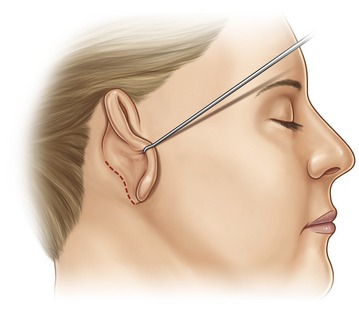

Surgery starts 20 minutes after injection. Following an initial preauricular incision, a thick skin flap is elevated superficial to the parotid fascia. Dissection stops at the line demarcating the anterior border of the parotid (Fig. 10.11).

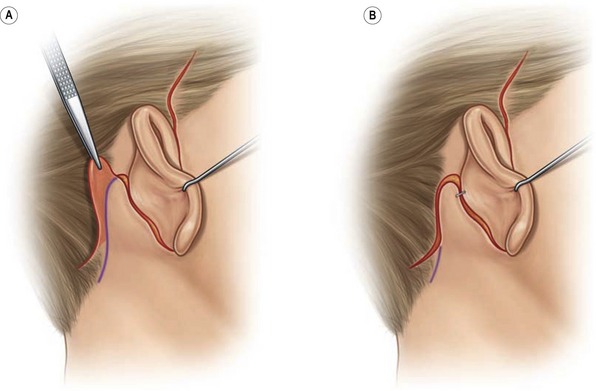

The skin with a thin layer of subcutaneous fat is elevated with the scalpel from the retroauricular and occipital area as far as the inked line denoting the lateral border of the platysma in the neck. This dissection is joined to the lower cheek dissection (Fig. 10.12).

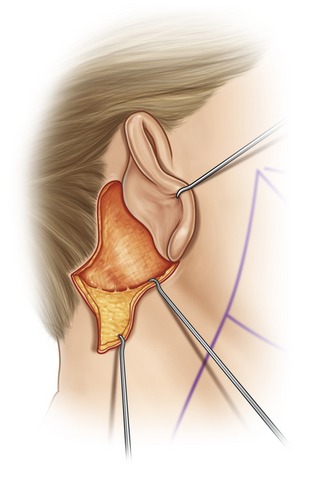

The skin of the neck overlying the platysma is also elevated using a long curved Mayo scissors. A 2–3 mm thickness of subcutaneous fat is kept with the skin. Residual fat on the platysma is excised with scissors or cautery. This dissection exposes the platysma from the mandibular border to as low in the neck as necessary. If laxity in the neck is severe, dissection will extend to the clavicle (Fig. 10.13A,B).

Fig. 10.13 Dissection superficial to platysma in upper (A) and lower (B) cervical area. Skin flap is raised with 2–3 mm of fat attached. Excess fat remaining on platysma is excised using scissors or cautery.

Subcutaneous dissection of the cheek flap is extended to the temporal area in the plane superficial to the superficial temporal fascia. This dissection continues to the region of the lateral border of the orbicularis oculi and the origin of the zygomaticus major and minor (Fig. 10.14).

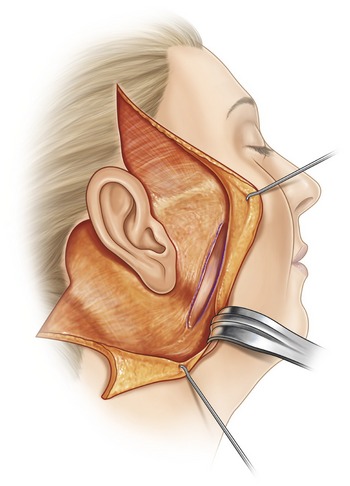

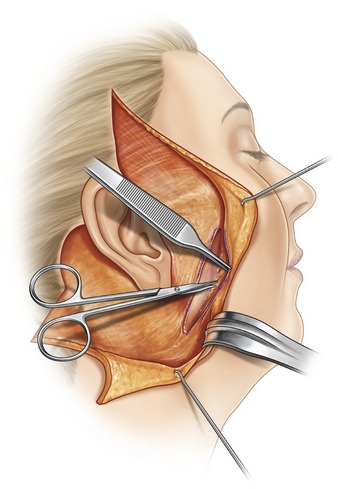

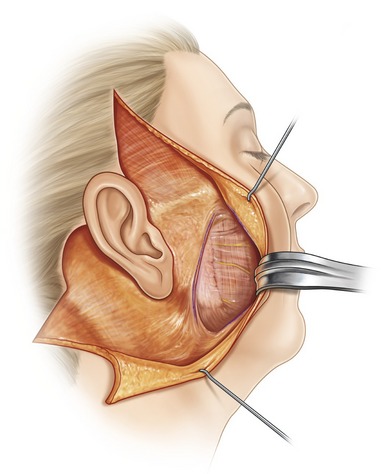

Entry to the deep plane is via scalpel incision through the SMAS-platysma along a line parallel to and 1 cm posterior to the anterior border of the parotid gland (Fig. 10.15). The surgeon grasps the cut edge of the platysma and begins separation of the platysma from the underlying parotid fascia using a pair of Stevens scissors (Fig. 10.16). As soon as the dissection proceeds in an anterior direction beyond the edge of the parotid gland, the platysma becomes much less adherent to the underlying masseteric fascia, and spreading of the scissors in a plane perpendicular to the plane of dissection easily separates the platysma from the masseteric and adjacent buccal fascia. Dissection is rapid and bloodless to the region of the modiolus and labiomental line (Fig. 10.17).

Fig. 10.17 Completed dissection in the lower cheek. Retractor elevates platysma. Beginning at the line of the incision to the deep plane (purple ink line) one sees parotid fascia, and masseteric fascia covering facial nerve branches.

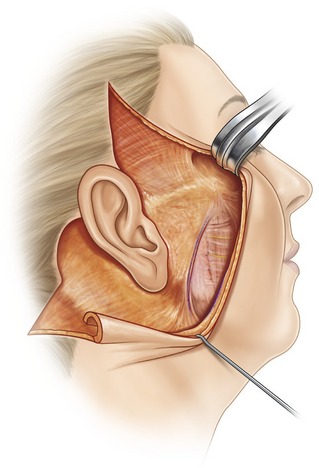

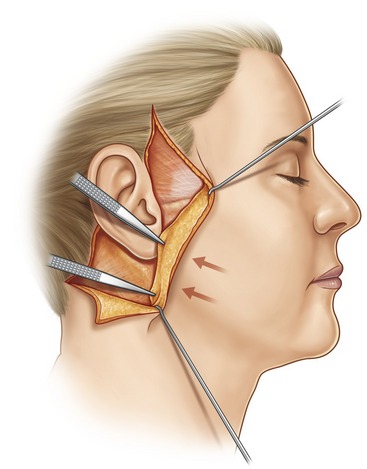

The upper cheek is dissected in the deep plane by finding the origin of the zygomaticus major near the most prominent portion of the malar eminence and then dissecting superficial to the zygomaticus major until the surgeon reaches the nasolabial fold (Fig. 10.18). The malar fat pad remains with the skin and is part of the elevated upper cheek flap. The upper and lower cheek dissections are connected by bluntly separating the remainder of the connections between the zygomaticus major and the skin.

Upon completion of the dissection of the right cheek and neck, the patient’s head is turned to the right and an identical dissection is performed on the left side. If the cervical soft tissues are lax, or, there is excess fat in the submental area, the anterior neck is approached through a 4 cm transverse submental incision (see Fig. 10.7). The submental skin is dissected away from the underlying platysma, leaving a 2–3 mm layer of fat on the undersurface of the skin. This dissection joins with the lateral dissections from the right and left sides. The entire submental and submandibular areas are then exposed, and any excess fat overlying the platysma is excised through the central submental and right and left lateral incisions. If necessary, the platysma is imbricated in the midline with a running 3-0 Monocryl suture (www.ethicon.com).

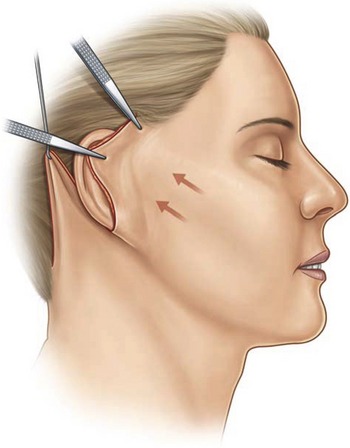

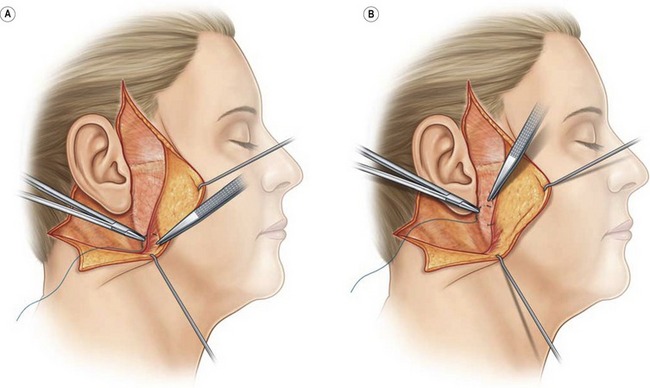

The patient’s head is turned to the left and the right SMAS-platysma flap is used to elevate and tighten the lower cheek and upper neck tissues (Fig. 10.19). The undersurface of the platysma and overlying subcutaneous tissue of the upper neck and cheek are sutured to the parotid fascia anterior to the earlobe with two sutures of 2-0 Maxon (www.ussurgical.com) (Fig. 10.20).

Fig. 10.19 SMAS-platysma and attached overlying skin are elevated and tightened using Bonney forceps.

Fig. 10.20 A, A 2-0 Maxon is placed in the undersurface of the platysma and B, sutured to the fixed parotid fascia anterior to the right earlobe. Two such sutures are placed, one above the other. When the sutures are tied the skin will be elevated and tightened.

The upper portion of the cheek flap is pulled upwards and laterally enough to increase dental show but not under extreme tension (Fig. 10.21). The upper cheek flap is then sutured with 3-0 Monocryl to the skin anterior to the point at which the helical rim joins the preauricular skin (Fig. 10.22). The suture also includes a bite of the deep temporal fascia to prevent anterior migration of the helix.

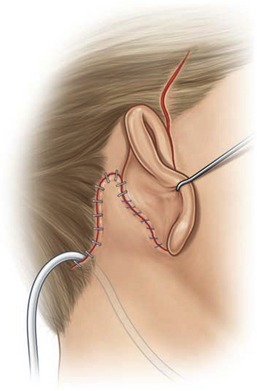

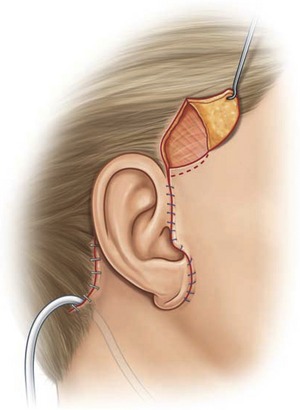

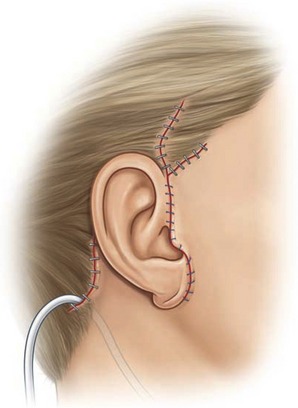

With the cervical skin under minimal tension, the excess skin behind the ear is marked and excised (Fig. 10.23). A suction drain is placed under the cervical flap at its most dependent area and leads out through an occipital stab wound. The occipital and hairline incisions are closed with staples (Fig. 10.24). The skin flap at the retroauricular crease will be sutured to the ear under no tension with absorbable 4-0 plain sutures.

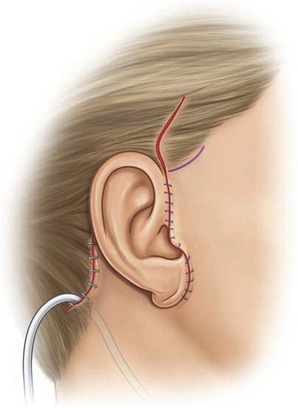

Excess skin in front of the ear is marked and trimmed so that skin edges touch the ear. The skin overlying the tragus is thinned by excising the subcutaneous fat with Stevens scissors. The cheek flap is sutured to the ear with interrupted 5-0 nylon sutures. The neotragal skin is sutured with 5-0 fast-absorbing plain gut (www.ethicon.com) (Fig. 10.25).

Excess skin in the temporal area is removed and the temporal hairline is lowered by incising the previously drawn transverse temporal hairline incision (Fig. 10.25). A triangle of skin is marked and excised at the point of insertion of the helical rim to the cheek (Fig. 10.26). After removing the excess skin above the point of insertion of the helical rim, the temporal hair flap is brought down and approximated to the adjacent skin in front of the ear, thus lowering the temporal hairline (Fig. 10.27).

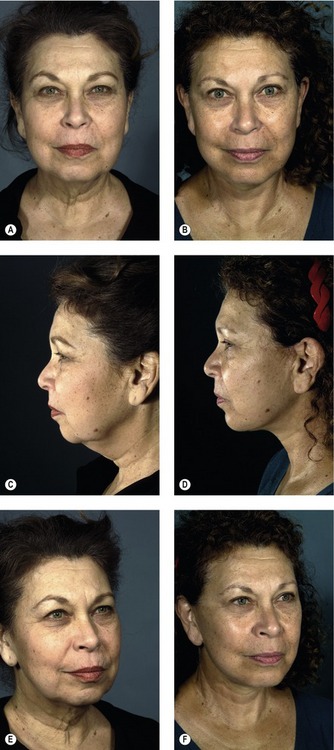

Results

Results are highly rejuvenating and durable, yet natural in appearance. The nasolabial folds and midface are particularly well addressed by foundation facelift. In the past, the technique sometimes produced suboptimal results in the neck because the change in planes from deep to the platysma in the cheek to superficial to the platysma in the neck limited the surgeon’s ability to tighten the cervical platysma from the lateral approach. Use of the corset platysmaplasty technique in conjunction with foundation facelift has, however, obviated this limitation (Fig. 10.28).

Complications

Although deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism are relatively uncommon, they can have devastating and sometimes fatal consequences. Patients who are seriously overweight or have multiple positive risk factors are generally refused surgery until they have reduced their risk. All patients are treated with intermittent compression devices during surgery.

Pearls & pitfalls

Pearls

• Have an intimate knowledge of the three dimensional anatomy of the facial nerve as it traverses the musculo-fascial planes of the face. Perform cadaver dissections to obtain this knowledge.

• Avoid excessive tension, especially at the skin closure.

• Use atraumatic technique to avoid injury to the subdermal vascular plexus.

• Investigate postoperative pain at the bedside immediately. Pain is a cardinal sign of postoperative hematoma.

• No single operation is optimal for all patients. Be prepared to vary technical details depending on the particular needs of your patient.

Pitfalls

• Avoid operating on obese patients. Obtaining quality results is difficult and sometimes impossible. Complication rates are higher.

• Avoid serious medical complications by participating with the patient’s internist in optimizing medical status prior to surgery.

• Do not underestimate the scope of the surgery to your patients. The more areas treated, the longer the recovery.

• Point out skin inelasticity, actinic damage, and other factors potentially limiting the results prior to surgery. Be prepared to offer ancillary treatments such as peels and lasers to mitigate the limitations of skin inelasticity and sun damage.

Hamra ST. Composite rhytidectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992;90:1–13.

Hamra ST. The deep-plane rhytidectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1990;86:53–63.

Gosain AK, Yousif NJ, Madiedo G, et al. Surgical anatomy of the SMAS: A reinvestigation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1993;92:1254–1263.

Lemmon ML, Hamra ST. Skoog rhytidectomy: A five-year experience with 577 patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1980;65:283–292.

Mendelson MC, Freeman ME, Wu W, et al. Surgical anatomy of the lower face: the premasseter space, the jowl, and the labiomandibular fold. Aesth Plast Surg. 2008;32:185–195.

Mitz V, Peyronie M. The superficial musculo-aponeuric system (SMAS) in the parotid and cheek area. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1976;58:80–88.

Pina DP. Asthetic and safety considerations in composite rhytidectomy: A review of 145 patients over a 3-year period. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;99:670–678.

Pitman GH. The deep-plane demystified. Videotape. St Louis: Quality Medical Publishing; 2000.

Rudolph R. Depth of the facial nerve in face lift dissections. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1990;85:537–544.

Skoog T. Plastic Surgery: New Methods and Refinements. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1974.