19.2 Forensic paediatrics and the law

Forensic medical assessment

Accurate history and examination and appropriate investigation

The following points may assist in forensic matters.

Physical injuries

It is important to document from whom each part of the history is obtained and any differing accounts. Any explanation that the child gives for the injury should be recorded.

It is important to document from whom each part of the history is obtained and any differing accounts. Any explanation that the child gives for the injury should be recorded. A child’s developmental abilities should be evaluated to ensure that any actions the child has allegedly taken are within their developmental ability, e.g. standing and turning on hot-water taps.

A child’s developmental abilities should be evaluated to ensure that any actions the child has allegedly taken are within their developmental ability, e.g. standing and turning on hot-water taps. Accurate terminology for injuries should be used e.g.:

Accurate terminology for injuries should be used e.g.:

If an injury or injuries are present, there must be careful examination for other abnormalities that might not be immediately obvious, e.g. a child with facial bruising should have careful examination of mouth and ears.

If an injury or injuries are present, there must be careful examination for other abnormalities that might not be immediately obvious, e.g. a child with facial bruising should have careful examination of mouth and ears. In addition to a child’s injuries, notice should also be taken of their general presentation, appearance and demeanour, and of any non-concerning injuries or skin markings.

In addition to a child’s injuries, notice should also be taken of their general presentation, appearance and demeanour, and of any non-concerning injuries or skin markings. When ED medical staff encounter injuries or findings that are suspicious of abuse or neglect they should, in the first instance, involve more senior staff, either a senior paediatric emergency physician, or a child protection paediatrician, for guidance.

When ED medical staff encounter injuries or findings that are suspicious of abuse or neglect they should, in the first instance, involve more senior staff, either a senior paediatric emergency physician, or a child protection paediatrician, for guidance. In consultation with senior staff, further testing for occult injury may be required when injuries or findings are suspicious for abuse or neglect e.g. skeletal survey in infants with bruising to look for occult fractures, or funduscopy with dilated pupils in infants with rib fractures, looking for retinal haemorrhages (see Table 19.2.1).

In consultation with senior staff, further testing for occult injury may be required when injuries or findings are suspicious for abuse or neglect e.g. skeletal survey in infants with bruising to look for occult fractures, or funduscopy with dilated pupils in infants with rib fractures, looking for retinal haemorrhages (see Table 19.2.1). Additional testing may also be indicated to exclude differential diagnoses and to assess for other factors that may impact on the extent of any injuries for a given history e.g. testing for bleeding tendency (Table 19.2.1).

Additional testing may also be indicated to exclude differential diagnoses and to assess for other factors that may impact on the extent of any injuries for a given history e.g. testing for bleeding tendency (Table 19.2.1). Specific forensic sampling may be required in some instances, e.g. toxicology, swabbing for DNA in suspected bites, or specimen collection in sexual abuse. Child protection or forensic physicians should be involved, and a clear ‘chain of evidence’ must be maintained from clinician to police to forensic pathologist.

Specific forensic sampling may be required in some instances, e.g. toxicology, swabbing for DNA in suspected bites, or specimen collection in sexual abuse. Child protection or forensic physicians should be involved, and a clear ‘chain of evidence’ must be maintained from clinician to police to forensic pathologist.CT, computerised tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PTH, parathyroid hormone.

Other circumstances

Sexual abuse allegations should be discussed with a child protection paediatrician as soon as possible and generally prior to any further assessment and physical examination.

Sexual abuse allegations should be discussed with a child protection paediatrician as soon as possible and generally prior to any further assessment and physical examination. Child protection concerns not specifically related to injury may arise in an ED context. These may include concerns of suspected emotional/psychological abuse, factitious illness and neglect e.g. non-organic failure to thrive, significant hygiene concerns, failure to attend to medical needs, concerning parent–child interactions.

Child protection concerns not specifically related to injury may arise in an ED context. These may include concerns of suspected emotional/psychological abuse, factitious illness and neglect e.g. non-organic failure to thrive, significant hygiene concerns, failure to attend to medical needs, concerning parent–child interactions.Legal obligations

Mandatory reporting of child abuse

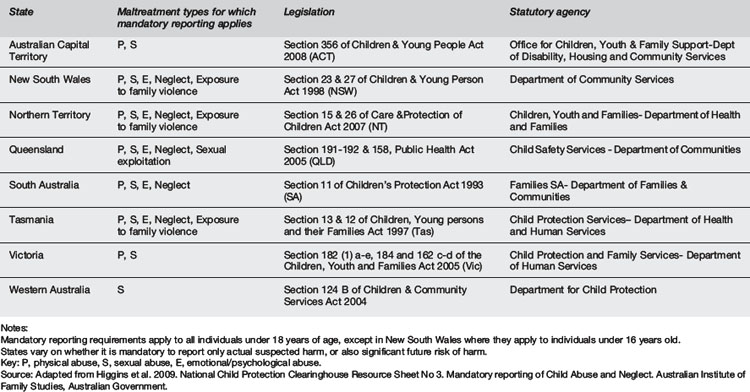

Medical practitioners in all states and territories of Australia are now mandated to notify suspicions of abuse and/or neglect to the relevant statutory authority in their state, although the forms of abuse/neglect to which mandatory reporting applies vary between states e.g. only sexual abuse in Western Australia, sexual/emotional/physical abuse and neglect in New South Wales (Table 19.2.2). Definitions of abuse commonly relate to the concept of harm, which, for example, under the Queensland Child Protection Act 1999, is defined as ‘any detrimental effect of a significant nature on the child’s physical, psychological or emotional wellbeing’. In many states, it is mandatory to report not only actual suspected harm but also significant risk of harm. Practitioners should be familiar with the requirements and mechanisms for notification within their state and locality. Doctors are free of any liability if such reports are made in good faith.

Legal jurisdictions

Criminal court

The statement should include details of professional qualifications and experience, a brief history provided to the doctor, and an accurate description of clinical findings. Reference should be made to any other documentation or investigation, e.g. photographs, so that they can be admitted as evidence. It is important to address whether the injuries found could produce effects consistent with the definition of the charges (Table 19.2.3). This usually requires comments as to effects on the child with regards to pain and suffering, and prognosis assuming medical intervention had not occurred. It is not appropriate to describe injuries as, for example, constituting ‘grievous bodily harm’ as this is for the court to determine.

Source: Derived from Queensland Criminal Code Act 1899.

Breen K., Plueckhahn V., Cordner S. Ethics, law and medical practice. Allen & Unwin, St. Leonards: NSW; 1997.

Dix A., Errington M., Nicholson K., Powe R. Law for the medical profession in Australia, 2nd ed. Port Melbourne: Butterworth-Heinemann; 1996.

Higgins D., Bromfield L., Richardson N., et al. National Child Protection Clearinghouse(NCPC) Resource Sheet No 3. Mandatory reporting of Child Abuse and Neglect. Australian Institute of Family Studies, Australian Government; 2009.

. Queensland Child Protection Act. 1999.

. Queensland Criminal Code Act. 1899.

Royal College of Paediatrics & Child Health (RCPCH). Child Protection Companion. 2006.

Royal College of Paediatrics & Child Health (RCPCH). Child Protection Reader. 2007.

Royal College of Paediatrics & Child Health (RCPCH). Standards for Radiological Investigation in Suspected Non-Accidental Injury. Intercollegiate Guideline RCPCH and Royal College of Pathologists; 2008.

Shepherd R. Simpson’s forensic medicine, 12th ed. London & Baltimore MD, USA: Hodder Arnold; 2003.