CHAPTER 25 Foreign Bodies, Bezoars, and Caustic Ingestions

GASTROINTESTINAL FOREIGN BODIES

GIFBs are a fairly common problem encountered by gastroenterologists. Most resolve without serious clinical sequelae.1 Older studies have suggested that between 1500 and 2750 deaths occurred in the United States secondary to GIFBs.2–4 More recent studies have suggested the mortality from GIFBS to be significantly lower, with no deaths reported in over 850 adults and only one death in approximately 2200 children with reported GIFB.5–11 However, regardless of imprecise morbidity and mortality rates, serious complications and deaths occur as a consequence of foreign body ingestions.12–14

EPIDEMIOLOGY

GIFBs may result from unintentional or intentional ingestion. The most common patient group that unintentionally ingests foreign bodies is children, particularly those between ages 6 months and 3 years. Children account for 80% of true foreign body ingestions.15 Children’s natural oral curiosity leads to placing objects in their mouth and occasionally swallowing them. Coins are the most common objects swallowed by children but other frequently swallowed objects include marbles, small toys, crayons, nails, and pins.6,10,16

Accidental ingestion may also occur in adults with dental covers or dentures because of loss of tactile sensation during swallowing.17 A not uncommon occurrence is a patient mistakenly ingesting one’s own dentures.18 Patients with altered mental status or sensorium, including the very old, demented, or intoxicated, are at risk for accidental foreign body ingestions (Fig. 25-1). Accidental coin ingestion has been noted in college-aged adults during a tavern beer drinking game called “quarters,” in which the coin becomes lodged in the esophagus.19 Finally, those in certain occupations, such as roofers, carpenters, seamstresses, and tailors are at risk of accidental ingestion when nails or pins are held in the mouth during work.

Figure 25-1. Endoscopic image of a bottle opener (in the stomach) ingested by an intoxicated patient.

The most common groups that intentionally ingest foreign bodies are psychiatric patients and prisoners.20 Ingestion in these groups of patients is often done for secondary gain; they often ingest multiple objects, multiple times, and often the most complex foreign bodies.

Iatrogenic foreign bodies are increasing in prevalence because of complications from capsule endoscopy, migrated stents (esophageal, enteral, and biliary), and migrated enteral access tubes and bolsters.21,22

Esophageal food impaction is the most common GIFB requiring medical attention in the United States, with an incidence of 16/100,000.23 The vast majority (75% to 100%) of patients with an esophageal food impaction have an underlying predisposing esophageal pathology,24–25 most often peptic strictures, Schatzki’s rings, and, increasingly, eosinophilic esophagitis.26 Other causes that contribute to esophageal food impactions include altered surgical anatomy following esophagectomy, fundoplication, or bariatric surgery and motility disorders such as achalasia and diffuse esophageal spasm.27

Food impactions most commonly occur in adults in their fourth or fifth decade of life but are becoming more prevalent in young adults because of the rising incidence of eosinophilic esophagitis. Cultural and regional dietary habits influence GIFBs. Fish bone injury is common in Asian countries and the Pacific rim, whereas impactions caused by meats, including hot dogs, pork, beef, and chicken, are common in the United States (Fig. 25-2).28,29

Symptomatic rectal foreign bodies are more often the result of insertion through the anus rather than oral ingestion and transit. This is reported most commonly in young adult males.30 Rectal foreign bodies that come to medical attention are most commonly inserted with the intention of autoeroticism but may present following consensual sexual acts or sexual assault.31 Less common, but still prevalent, causes of rectal foreign bodies include concealment of illegal drugs during smuggling efforts, loss of objects during attempts by the patient to relieve constipation, and even reports of falling on objects.32

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The vast majority (approximately 80% to 90%) of gastrointestinal foreign bodies pass through the gastrointestinal (GI) tract without any clinical sequelae and cause no harm to the patient.1,33 The remaining 10% to 20% of GIFBs will require endoscopic intervention and 1% of GIFBs may require operative therapy.5,34 True foreign bodies and food impactions can cause significant morbidity, with the most serious complications being bowel perforation or obstruction and ensuing death.3 Thus, it is important to understand the conditions in which complications associated with GIFBs are apt to occur to help stratify therapeutic interventions.

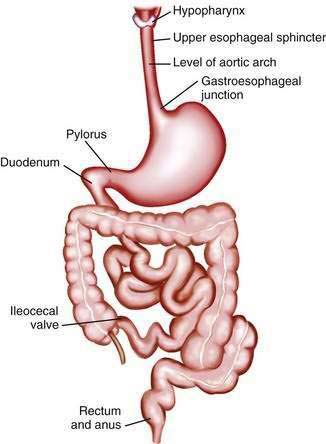

Perforation and obstruction from GIFB can occur in any part of the digestive tract, but are more apt to occur in areas of narrowing, angulation, anatomic sphincters, or previous surgery (Fig. 25-3).35 The posterior pharynx is the first area in which foreign bodies may become entrapped and cause complications. In the hypopharynx, short sharp objects such as fish bones and toothpicks may lacerate the mucosa or become lodged.36,37

Figure 25-3. Gastrointestinal areas of luminal narrowing and angulation that predispose to foreign body impaction and obstruction.

Once in the esophagus, there are four areas of narrowing at which food boluses and foreign bodies become lodged, including the upper esophageal sphincter, level of the aortic arch, level of the main stem bronchus, and gastroesophageal junction. These areas are all luminal narrowings of 23 mm or less.38 However, food impactions and foreign bodies more commonly lodge in the esophagus at areas of pathology, including rings, webs, or strictures. Multiple esophageal rings associated with eosinophilic esophagitis (see Chapter 27) contribute to esophageal food impaction at an increasing prevalence in young adults.26,39,40 Similarly, esophageal motor abnormalities (see Chapter 42) such as diffuse esophageal spasm, achalasia, or segmental variation in peristalsis may lead to food or foreign body impaction in the esophagus.41–44 Foreign body and food impaction in the esophagus generally have the highest incidence of overall adverse events, with the complication rate being directly proportional to how long the object is lodged in the esophagus. Serious complications of esophageal foreign bodies include perforation, abscess, mediastinitis, pneumothorax, fistula formation, and cardiac tamponade.45,46

Objects may become obstructed in the small intestine at the ligament of Treitz or at the ileocecal valve. Adhesions, postinflammatory strictures, and surgical anastomoses within the small intestine may also be sites where foreign bodies lodge and become obstructed. However, most objects, even sharp ones, rarely cause damage once in the small intestine and colon because the bowel naturally protects itself through peristalsis and axial flow; these tend to keep the foreign body concentrated in the center of fecal residue, with the blunt end leading and the sharp end trailing.47,48

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

The history from children or noncommunicative adults is often unreliable. Most gastric and up to 20% to 30% of esophageal foreign bodies in children are asymptomatic.49 Most of these present after having been witnessed or suspected by a parent, caregiver, or older sibling. However, in up to 40% of cases, there is no history of a witnessed ingestion.50 Thus, symptoms are often subtle in children, presenting as drooling, not wanting to eat, and failure to thrive.

For communicative adults, history of the timing and type of ingestion is usually reliable. Patients are able to relate exactly what they ingested, when they ingested it, and symptoms of pain or/and obstruction. Patients with esophageal food bolus impactions are symptomatic, with complete or intermittent obstruction. They are unable to drink liquids or retain their own oral secretions. Sialorrhea is common. Ingestion of an unappreciated small, sharp, object, including obscured fish or animal bones, may cause odynophagia or a persistent foreign body sensation because of mucosal laceration. The type of symptoms can aid in determining whether an esophageal foreign object is still present. If the patient presents with dysphagia, odynophagia, or dysphonia, there is an 80% likelihood that a foreign body is present, causing at least partial obstruction. Symptoms of drooling and inability to handle secretions are indicative of a near-total obstruction of the esophagus. If the symptoms are restricted to retrosternal chest pain or pharyngeal discomfort, less than 50% of patients will still have a foreign body present.51 Patient localization of where an ingested foreign object is lodged is not accurate, with only a 30% to 40% correct localization in the esophagus and essentially a 0% accuracy for foreign bodies in the stomach.49,52 Once the object reaches the stomach, small intestine, or colon, the patient will not report symptoms unless a complication occurs, such as obstruction, perforation, or bleeding.

Patients with rectal foreign bodies are frequently asymptomatic,31 but obtaining an accurate history from the patient may be difficult because of the embarrassment associated with its insertion. Presentation is often after the patient or another person has made multiple attempts to remove the object.36 Symptoms may include anorectal pain, bleeding, and pruritus, with a small number of patients presenting with more serious complications, including obstruction, perforation, and peritonitis.

DIAGNOSIS

Diagnostic Imaging

Plain films of the chest and abdomen are recommended for patients presenting with suspected foreign body ingestion to determine the presence, type, number, and location of foreign objects present. Both anteroposterior and lateral films are needed, because lateral films will aid in determining if a foreign body is in the esophagus or the trachea53 and may detail foreign bodies obscured by the overlying spine in an anteroposterior film. Biplanar neck films are recommended if there is a suspected object or complication in the hypopharynx or cervical esophagus. Plain films are also useful in identifying complications such as free air, aspirations, or subcutaneous emphysema (Fig. 25-4).54

Unfortunately, radiography is unable to diagnose nonradiopaque objects such as plastic, glass, or wood and may miss small bones or metal objects. The false-negative rate for plain film investigation of foreign bodies is as high as 47%, with false-positive rates up to 20%. Thus, if there is continued clinical suspicion or symptoms, the individual should undergo further clinical investigation.55

Use of plain films in children is more controversial because of the inability of the child to give a history and the radiation associated with the x-rays. Some have suggested mouth to anus screening films to detect the presence of foreign bodies in children. To limit radiation, hand-held metal detectors have been used, with a sensitivity higher than 95% for the detection and localization of metallic foreign bodies.56

Barium studies are generally not recommended for the evaluation of GIFBs. Aspiration of hypertonic contrast agents in patients with complete or near-complete esophageal obstruction may lead to aspiration pneumonitis.57 Furthermore, barium may delay or impair the performance of a therapeutic endoscopic intervention by interfering with endoscopic visualization.58 Also, even if a barium study is considered normal, an endoscopy is still recommended if symptoms persist or the suspicion of a foreign body is high.36

Imaging such as computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) rarely is needed for the diagnosis of GIFBs. However, CT has been found to detect foreign bodies missed by other modalities59 and may aid in detecting complications of foreign body ingestion, such as perforation or abscess, prior to the use of endoscopy.60

TREATMENT

Nonendoscopic Methods

Treatment of gastrointestinal foreign bodies should always be planned with the knowledge that 80% to 90 % of GIFBs will spontaneously pass through the GI tract without complication.5,8 This has led some investigators to suggest that all foreign bodies can be managed with conservative observation.61,62 Although conservative management is effective in most cases of GIFB, it is more appropriate to perform selective endoscopy for treatment based on the location, size, and type of foreign body ingested.20,63

A number of medical therapies have been considered as primary treatment of esophageal foreign bodies and food impactions. The smooth muscle relaxant glucagon is the most widely used and studied drug for the treatment of esophageal food and foreign object impactions. Glucagon, given in doses of 0.5 to 2.0 mg, can produce relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter by as much as 60%, with the potential to permit passage of the impacted food or foreign body.64,65 Success with glucagon ranges from 12% to 58% in treating food impactions.66–68 Glucagon may cause nausea, vomiting, and abdominal distention. In addition, glucagon has little effect when a fixed obstruction is present, preventing passage of the foreign body. Nifedipine and nitroglycerin are not recommended because of hypotension-related side effects.

The use of gas-forming agents such as carbonated beverages or preparations consisting of sodium bicarbonate and citric acid have been described for treating esophageal impactions. These agents are purported to release carbon dioxide gas to distend the lumen and act as a piston to push the object from the esophagus into the stomach.69 However, the effectiveness of this method is doubtful, and perforations have been reported associated with the use of gas-forming objects.70 Similarly, the meat tenderizer papain is not recommended for the treatment of esophageal meat impactions because of lack of efficacy and risk of complications, including perforation and mediastinitis.71,72

Radiologic methods have been described for the treatment of esophageal foreign bodies. Under fluoroscopic guidance, Foley catheters, suction catheters, wire baskets, and magnets have been used to retract objects.73 The most commonly described device is the Foley catheter; the balloon tip of the catheter is passed distal to the object, inflated, and then the object is withdrawn into the oropharynx. Success of Foley catheter extraction of esophageal foreign bodies under fluoroscopy has been described as more than 90%. However, all radiographic methods suffer from lack of control of the object, particularly at the level of the upper esophageal sphincter and hypopharynx. Complications may include nosebleeds, laryngospasm, aspiration, perforation, and even death.74 Radiographic methods are generally recommended only if flexible endoscopy is not available.

Endoscopic Methods

Flexible endoscopy has become the treatment of choice for gastrointestinal food impactions and foreign bodies because it is safe and highly efficacious. Multiple large series have reported the success rate for endoscopic treatment of GIFBs to be more than 95%, with complication rates of less than 5%.5,58,63,75–78 The risk for complications is increased when sharp or multiple objects are ingested and when the ingestion is intentional as opposed to accidental.

Because most GIFBs pass spontaneously without causing symptoms, it is important to understand the indications and timing for endoscopic intervention. Generally, all foreign bodies lodged in the esophagus require urgent intervention. The risk for an adverse outcome from an esophageal foreign body or food impaction is directly related to how long the object or food dwells in the esophagus.79 Ideally, no object should be left in the esophagus longer than 24 hours.

Once in the stomach, most ingested objects will pass spontaneously and the risk of complications is much lower, thus making observation acceptable. There are notable exceptions, as follows. Sharp and pointed objects are associated with perforation rates as high as 15% to 35%.79 Objects longer than 5 cm and round objects wider than 2 cm also may not be passed and should be removed from the stomach with an endoscope at presentation or if they have not progressed in three to five days. If a more complex or sharp object has progressed beyond the stomach and cannot be retrieved, periodic radiographs should be obtained to document progression through the GI tract.80 The patient should then be followed for any symptoms suggestive of obstruction or perforation, such as fever, tachycardia, abdominal pain, or distention.

The type of sedation selected to facilitate endoscopy for the management of food impactions and ingested foreign objects should be individualized. Although conscious sedation is adequate for the treatment of most food impactions and simple foreign bodies in the adult population, anesthesia assistance may be required for uncooperative patients or patients who have swallowed multiple complex objects (see Chapter 40).

For management of impactions and ingestions below the level of the laryngopharynx, flexible endoscopy is preferred.81 Rigid esophagoscopy and flexible nasoendoscopes can be used, but provide no additional benefit and are often available to only a few endoscopists.82,83 Laryngoscopes with the aid of a Kelly or McGill forceps can be useful for proximal foreign bodies and small sharp objects in the hypopharynx.

Availability of and familiarity with multiple endoscopic retrieval devices for the removal of foreign bodies and food impactions is critical (Table 25-1). An endoscopy suite and/or travel cart should be equipped with at least a grasping forceps, polypectomy snare, Dormia basket, and retrieval net.84 Overtubes of 45 and 60 cm in length should be available to the endoscopist. An overtube allows protection of the airway, multiple exchanges of the endoscope, and mucosal protection from sharp objects. The longer 60-cm overtube enables retrieval of sharp and complex objects from the stomach, bypassing the lower esophageal sphincter. An alternative adjunct for extraction of sharp objects is a latex protection hood, which fits onto the tip of the endoscope85,86 (see later).

Table 25-1 Equipment for Treatment and Removal of Gastrointestinal Foreign Bodies and Food Impactions

| ENDOSCOPES | OVERTUBES | ACCESSORY EQUIPMENT |

|---|---|---|

When planning for extraction of complex, sharp, or pointed ingested objects, and when opportunity permits, it may be valuable to go through an ex vivo dry run on a similar object when considering retrieval devices and extraction technique.5 Success and speed of retrieval of the foreign body have been shown to be directly related to endoscopist experience.87 When personnel or facilities are not available to accomplish relief endoscopically, consideration should be given to transferring the patient to another center.

SPECIFIC FOREIGN BODIES

Food Impaction

Food impaction is the most common ingested foreign body in the United States.27 The most common foods to cause impactions in the United States are meat products, including beef, hot dogs, and chicken. Fish bone impactions are more common in coastal areas and Asian countries. Imbibing alcohol while eating large cuts of meat may increase the risk for food impactions and has led to the terms backyard barbecue syndrome and steakhouse syndrome.

Given that food boluses may pass spontaneously, the need for endoscopic intervention is based on the persistence of symptoms. Patients with signs of complete or near-complete obstruction with drooling or excessive salivation should undergo urgent upper GI endoscopy. Endoscopic intervention should be achieved at the latest within 24 hours of onset of symptoms and more ideally within the first 6 to 12 hours. An increased risk for complications is thought to be proportional to the duration of esophageal food impaction.1,17,88

The primary method to treat food impaction is the push method, with success rates well over 90% and with minimal complications.24 Before the food impaction is pushed into the stomach, an attempt to steer the endoscope around the food into the stomach should be made. Generally, if the endoscope can be passed around the food impaction into the stomach, the food impaction can be safely pushed into the stomach without difficulty. This also allows assessment of any obstructive esophageal pathology beyond the food impaction. Even if the endoscope cannot steer around the food impaction, gentle pushing pressure can be safely attempted. Larger boluses of impacted meat can be broken apart with the endoscope or an accessory prior to pushing the smaller pieces into the stomach safely.

Eosinophilic esophagitis has increasingly been associated with esophageal food impactions (see Chapter 27). Reports indicate that food impaction in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis can be treated effectively and safely with the push method.39 However, care should be taken to minimize inducing mucosal tears.89

Food impactions that cannot be gently pushed into the stomach must be dislodged and withdrawn. Retrograde removal can be achieved with various retrieval devices, including snares, baskets, and forceps. Initial manual disruption of the food bolus into smaller pieces typically makes removal easier. An oroesophageal overtube is useful in such cases because it protects the airway and allows multiple exchanges of the endoscope during retrieval. A dedicated food bolus retrieval net can be useful for removing large pieces of food without the use of an overtube because the food can be satisfactorily secured within the net, thus reducing the risk of aspiration of the ingestate.90

Transparent plastic hoods or caps, such as those used to perform variceal band ligation and endoscopic mucosal resection, have been used successfully for the removal of large, tightly impacted meat boluses. With the cap secured to the tip of the endoscope, the device can be used to suction the food into the vacuum chamber and to withdraw the bolus per os.91,92

More than 75% of patients with food impactions have associated esophageal pathology.5,25 In addition, approximately half of patients with food bolus impactions have abnormal 24-hour pH studies and/or esophageal manometry. If an esophageal stricture or Schatzki’s ring is present after the food bolus is cleared, it can be safely and effectively dilated concurrently if circumstances allow. More often, mucosal abrasions or erythema exists from the food dwelling in the esophagus for an extended period and dilation is delayed for 2 to 4 weeks, during which patients should be prescribed proton pump inhibitor therapy. When multiple esophageal rings are present, biopsies should be obtained to evaluate for eosinophilic esophagitis.

Sharp and Pointed Objects

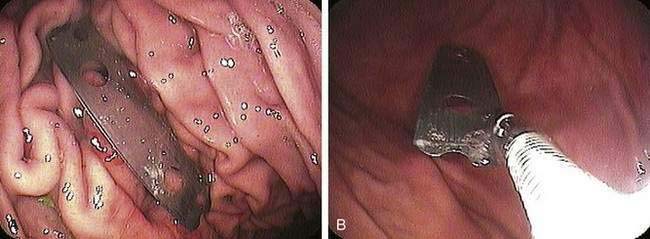

Sharp and pointed objects may cause a perforation in up to 15% to 35% of patients and account for one third of all perforations from GI foreign bodies.93 Sharp and pointed objects, particularly toothpicks and animal bones, are the most likely ingested foreign objects to cause a perforation that necessitates surgical management.94 Patients with psychiatric illness and incarcerated patients are more likely to ingest more complex and multiple sharp and pointed objects, such as razor blades (Fig. 25-5), pins, needles, and writing and eating utensils (Fig. 25-6).

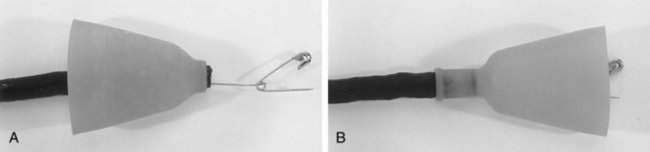

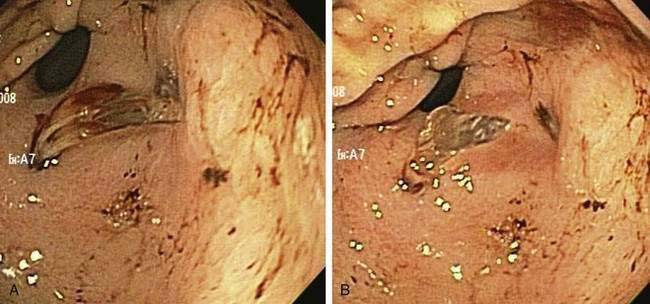

Sharp and pointed objects retained in the esophagus are considered a medical emergency and should be removed within 6 to 12 hours. Moreover, any sharp and pointed object within the reach of the endoscope should be removed as well if this can be safely done (Fig. 25-7). When removing sharp and pointed objects, the foreign body should be grasped and oriented so that the pointed end trails on withdrawal to reduce the risk of perforation and mucosal laceration.95

Figure 25-7. Endoscopic images of shards of broken glass in the prepyloric antrum.

(Courtesy of Dr. Jamie Anderson and Dr. Tushar Dharia, Dallas, Tex.)

For sharp and pointed objects, retrieval is best achieved with a grasping forceps, polypectomy snare, or biliary stone retrieval basket.87 All these devices can secure the object; orient the device used as described earlier. Retrieval nets tend to shear in the removal of sharp objects and may compromise visualization.

An alternative to an overtube for the extraction of sharp and pointed objects is a retractable latex hood that can be affixed to the tip of the endoscope (Fig. 25-8). When the endoscope is pulled back through the lower esophageal sphincter, the hood flips over the grasped object and protects the mucosa during withdrawal.85,96

Long Objects

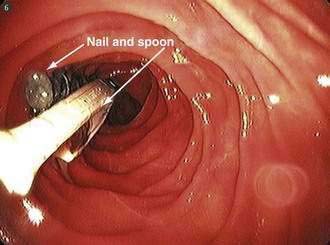

Ingested objects longer than 5 cm (2 inches), and especially those longer than 10 cm (4 inches), have difficulty passing through the pylorus and duodenal sweep and can get hung up, causing obstruction or perforation at these locations (see Fig. 25-7). The most commonly ingested long objects are pens, pencils, toothbrushes, and eating utensils. Grasping forceps and polypectomy snares are the most commonly used devices to secure and remove long objects. Long objects should be grasped at one end and oriented longitudinally to permit removal. For extraction of long objects, use of the 60 cm overtube endoscope assembly, as described earlier, should be considered.

Blunt Objects: Coins, Disc Batteries, Magnets, and Bread Tabs

Polyp or dedicated retrieval nets allow capture and secure removal.87 Grasping forceps and biliary stone retrieval baskets are also effective. Standard biopsy forceps and snares are not recommended because they fail to secure coins reliably during extraction. If it is difficult to capture a blunt object in the esophagus, it is safe to push the object into the stomach, where there is more room to negotiate.

Once a small blunt object enters the stomach, conservative outpatient management is appropriate for most patients.97 Exceptions to this include patients with surgically altered digestive tract anatomy and those who have ingested large blunt objects. In adults, the pylorus will allow passage of most blunt objects up to 25 mm in diameter, which includes all coins except half-dollars (30 mm) and silver dollars (38 mm). Otherwise, once in the stomach, a regular diet is appropriate, with radiographic monitoring every one to two weeks to confirm progression or elimination. If after three to four weeks a blunt object has not passed, endoscopic removal should be performed.98

Disc batteries are now contained in many small toys and electronic devices that are accessible to young children. Disc battery ingestion is of particular concern because batteries contain an alkaline solution, which can cause rapid liquefaction necrosis in the esophagus. Disc battery ingestion occurs most commonly in younger children but as few as 10% will become symptomatic.99 Therefore, any clinical suspicion of a disc battery in the esophagus should prompt emergent endoscopy. Grasping forceps and snares are generally ineffective for disc battery removal, but use of a retrieval net permits successful removal in almost 100% of cases.100 Once in the stomach or small intestine, disc batteries rarely cause clinical problems and can be observed radiographically, with 85% passing through the GI tract within 72 hours.101

Small, brightly colored, coupling magnets have become popular as children’s toys. Ingested magnets within the reach of the endoscope should also be removed on an urgent basis. Although a single magnet will rarely be a cause of symptoms, concern exists if multiple magnets are ingested or if magnets were ingested with other metal objects. This can result in magnetic attraction and coupling between interposed loops of bowel with subsequent pressure necrosis, fistula formation, and bowel perforation.102,103 Removal should be performed urgently when the magnets are more likely to be within reach of a standard endoscope; this can be achieved with grasping forceps, retrieval net, or basket. Magnetic attraction to metallic retrieval devices may ease the task of removal.

Bread tabs or bread bag clips are another otherwise seemingly innocuous blunt object that when ingested (usually unknowingly) have been associated with a high risk for gastrointestinal tract complications.104 Bread bag clips, introduced in the 1950s, are ubiquitous in developed societies. Bleeding, bowel obstruction, and perforation have all been described. The small bowel is the most common site of impaction, where the arms of the clip tenaciously grasp the mucosa. Esophageal and large bowel injury have also been described. Management is problematic in that ingestion is typically not detected until complications arise. Bread bag clips are radiolucent and, as such, are not detected by conventional radiography. When recognized at endoscopy, an attempt at removal is justified, using a gasping forceps; however, operative intervention is commonly required.

Narcotic Packets

Ingested packets of illicit narcotics in the GI tract present in two general groups, termed body stuffers and body packers. Body stuffers are drug users or traffickers who quickly ingest small amounts of drugs, but in poorly wrapped or contained packages that are prone to leakage. Body packers are the mules used by drug smugglers who ingest large quantities of carefully prepared packages intended to withstand GI transit.105,106 These patients may present with intestinal obstruction because of the packages or symptoms related to the drug ingested. The latter may result in serious toxicity and death in 5% of these mules.107

Suspected patients are typically uncooperative and accompanied by law enforcement agents. Diagnosis is initiated with plain film radiology or CT scan, with multiple round or tube-shaped packets seen. Endoscopic removal is contraindicated because of the high risk of package perforation with resultant drug overdose.1 Observation on a clear liquid diet is recommended. Operative intervention is indicated when bowel obstruction or drug leakage is suspected.

Colorectal Foreign Bodies

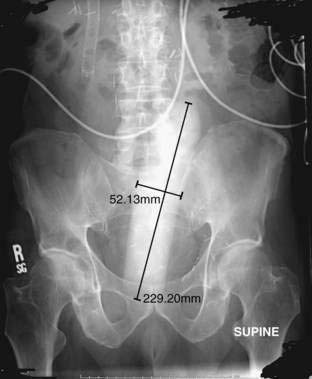

Ingested objects uncommonly become lodged in the colorectum. More commonly, colorectal foreign bodies were inserted into the rectum intentionally or unintentionally. Radiographs should be obtained prior to attempting removal of colorectal foreign bodies for better visualization of the location, orientation, and configuration of the object (Fig. 25-9). To avoid health care provider injury, attempts at manual removal or digital rectal examination should be deferred until the presence of a sharp or pointed object has been excluded.

Figure 25-9. A self-introduced rectal foreign body is apparent in a 73-year-old man presenting with lower abdominal pain.

(Courtesy of Dr. William Beaujohn, Plano, Tex.)

Nonpalpable and sharp or pointed objects should be removed under direct visualization with the use of a rigid proctoscope or flexible sigmoidoscope.108 Standard retrieval devices can be used as described earlier for the upper digestive tract. A latex hood or overtube can be particularly useful in removing long, sharp, pointed objects to protect the rectal mucosa from laceration and to overcome the tendency of the anal sphincter to contract on attempted removal of objects. Although conscious sedation will often facilitate removal, general anesthesia can allow maximum dilation of the anal sphincter to help remove larger and more complex objects.109

Operative intervention is indicated for any suspected complications secondary to a rectal or colon foreign body, including perforation, abscess, and obstruction. Complications are more common when the object is proximal to the rectum.110

PROCEDURE-RELATED COMPLICATIONS

Although the reported complication rate associated with endoscopic removal of gastrointestinal foreign bodies and food impactions is low (0% to 1.8%), it is thought to be much higher in practice.5,9,23,24,58,78 Perforation is the most feared complication, although aspiration and sedation-related cardiopulmonary complications may also occur (see Chapter 40). Factors that increase the risk for complications include removal of sharp and pointed objects, an uncooperative patient, multiple and/or deliberate ingestion, and extended duration of time from food impaction or foreign body ingestion.12

BEZOARS

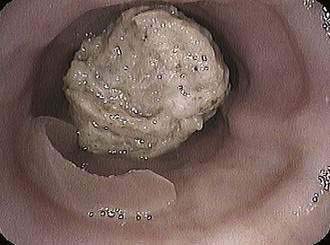

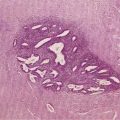

Bezoars are collections of indigestible material that accumulate in the gastrointestinal tract, most frequently in the stomach. The three most common types of bezoars encountered are phytobezoars, composed of vegetable matter; trichobezoars, made up of hair or hair-like fibers; and medication bezoars (pharmacobezoars) (Fig. 25-10; Table 25-2).

Table 25-2 Oral Pharmacologic Agents Associated with Medication Bezoar Formation

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Phytobezoars are the most common type of bezoar. Offending fruits and vegetables include celery, pumpkin, prunes, raisins, leeks, beets, and persimmon.5 All these foods contain large amounts of insoluble and indigestible fibers, such as cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin, and fruit tannin.111 A phytobezoar develops when large quantities are ingested and accumulate.

Trichobezoars occur most commonly in young women and children from ingestion of large amounts of hair, carpet fiber, or clothing fiber. Trichobezoars are more often associated with psychiatric disorders, mental retardation, or pica.112

Medication bezoars occur with fiber-containing medications, resin-water products, or extended-release medications designed to resist digestion.113 Medication bezoars can result in decreased pharmacologic efficacy when the active agent is trapped in the bezoar and cannot be absorbed or, alternatively, increased toxicity when the contents of a large gastric medication bezoar are released all at once into the small intestine.

The vast majority of patients with bezoars (other than trichobezoars) have a predisposing factor that decreases emptying of gastric contents. Prior gastric surgery is evident in as many as 70% to 94% of patients with bezoars. Retained gastric contents may be observed in up to 65% to 80% of patients who have undergone a vagotomy with pyloroplasty.52 Bezoar formation after surgery results from delayed gastric emptying, decreased gastric accommodation, and reduced acid-peptic activity.114 Gastroparesis is commonly seen in patients with gastric bezoars. Patients with diabetes or end-stage renal disease, and patients on mechanical ventilation, are all at greater risk for bezoar formulation.115

CLINICAL FEATURES

Patients with gastric bezoars may be asymptomatic, but most (80%) have vague symptoms of epigastric discomfort.115 Associated anorexia, nausea, vomiting, weight loss, and early satiety may also be present. Bezoars can cause gastric ulceration secondary to pressure necrosis. Bezoar-induced gastric ulcers can cause bleeding and gastric outlet obstruction.116

Bezoars may also accumulate in the small bowel and usually present with mechanical obstruction. Rapunzel syndrome is a term used to describe trichobezoars located primarily in the stomach that extend past the pylorus and into the duodenum, causing bowel obstruction or even jaundice or pancreatitis because of obstruction at the level of the ampulla of Vater.117,118

DIAGNOSIS

A plain abdominal radiograph may demonstrate the outline of the bezoar. On contrast radiography, a gastric bezoar classically presents as filling defects within the stomach.111 Plain films and contrast studies will detect only 25% of bezoars detected at upper endoscopy, however. Therefore, gastric bezoars are definitively diagnosed with upper endoscopy. On upper endoscopy, phytobezoars are a dark brown, green, or black mass of amorphous vegetable material in the stomach. Trichobezoars tend to have a hard, blackened, and almost concrete appearance. Medication bezoars will be seen as whole pills or pill fragments in the midst of the material (see Fig. 25-10).

TREATMENT

Smaller bezoars may be treated with conservative medical management; usually, this consists of a liquid diet for a short period of time and a prokinetic agent to promote gastric emptying.111 Chemical dissolution, most commonly with cellulase, has been reported successful in up to 85% of patients with small bezoars.116 Cellulase can be taken as a tablet or instilled into the stomach as a liquid via an endoscope or nasogastric tube. Nasogastric lavage may aid in the physical dissolution of small bezoars.

For larger bezoars and bezoars resistant to medical therapy, endoscopic therapy may be effective. The endoscope is used to fragment the bezoar into smaller pieces. Fragmentation can be performed with the endoscope itself, with accessory devices such as forceps or snares, or with the instillation of saline or water flushes through the endoscope. The fragments of the bezoar can be pushed into the small bowel or removed by mouth. If most of the bezoar is to be removed, an overtube is recommended to facilitate frequent passes of the endoscope and to protect the airway. Mechanical disruption and endoscopic removal will be successful in 85% to 90% of gastric bezoars. Resistant gastric bezoars may be treated with mechanical lithotripsy, electrohydraulic lithotripsy, Nd:YAG laser, or a needle-knife sphincterotome.119–121

Operative intervention may be needed if endoscopic therapy fails or if there is a complication related to the bezoar, such as a perforation, obstruction, or bleeding. Trichobezoars typically require surgery more often than phytobezoars. Gastric bezoars are usually removed via a small gastrostomy.116,118 Small bowel bezoars are removed via an enterotomy or can be transmurally milked to the cecum, where they rarely cause a problem in the larger diameter colon. When operative intervention is contemplated, care must be made to exclude multiple bezoars in more than one location.

CAUSTIC INGESTIONS

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Approximately 5000 caustic ingestions are reported annually in the United States.122 Most caustic ingestions occur as accidental ingestions by children younger than 6 years.123 Caustic ingestions in adults occur as suicide attempts, in patients with mental health problems, and in the intoxicated person as a result of alcohol or recreational drug ingestion. Adults may tend to have more serious injuries because of ingesting larger amounts of caustic substances as compared with children, who will spit out or throw up the caustic agent that was swallowed.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Alkali

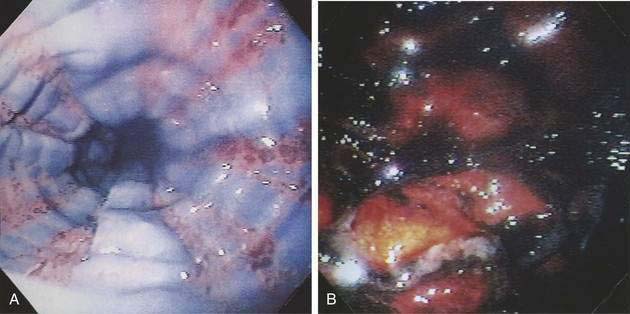

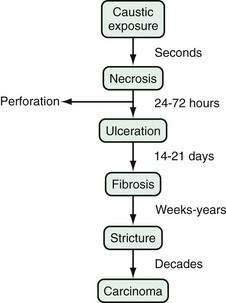

Alkaline ingestion causes a liquefactive necrosis that very rapidly extends through the mucosa, submucosa, muscularis of the esophagus, and stomach.124 Vascular thrombosis occurs following the necrosis. The initial alkali injury can be transmural and can result in perforation, mediastinitis, and peritonitis.125 External sloughing and ulceration occur a few days after ingestion. Finally, extensive granulation tissue, fibroblastic activity, and collagen deposition occur over weeks, leading to chronic stricture formation (Fig. 25-11). With alkali ingestion, the esophagus is affected the most, with some limitation of damage in the stomach because of neutralization by acid; a minority of patients have damage in the small intestine as well.126 The degree of injury is also dependent on the agent ingested, its quantity, and how long the GI tract was exposed to the agent.127

Acid

Acidic agents cause a coagulative necrosis, with thromboses of mucosal blood vessels and a more limited superficial necrosis. Acidic agents are more apt to damage the stomach, particularly the antrum, more than the esophagus (Fig. 25-12). Furthermore, acidic agents tend to be ingested in a smaller quantity because of their offensive taste and immediate pain. Thus, acidic ingestions are associated with less overall damage compared with alkali agents.

CLINICAL FEATURES

Patients may present with oropharyngeal pain, epigastric pain, chest pain, dysphagia, or odynophagia. Oropharyngeal involvement can cause sialorrhea and drooling. Hoarseness, stridor, and dyspnea suggest injury to the epiglottis, larynx, and upper airway. Persistent chest or back pain may suggest esophageal perforation and mediastinitis, whereas severe abdominal pain can be related to gastric perforation and peritonitis. Of importance is that early signs and symptoms do not always correlate with the amount of caustic injury and likelihood for late complications.128 On physical examination, patients may have evidence of burns to the oral cavity with edema, ulceration, and exudate, but as many as 20% to 45% of patients will have normal physical examinations.129

DIAGNOSIS

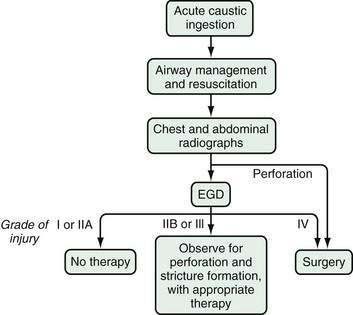

Radiologic images such as chest x-ray and abdominal films will not aid in the direct diagnosis or grading of severity of injury, but will indicate the presence of perforation by showing a pneumomediastinum, pneumothorax, or pneumoperitoneum. CT of the neck, chest, and/or abdomen should be considered when a high degree of suspicion remains for perforation, despite negative plain films. If perforation is present, surgery rather than endoscopy should be performed emergently (Fig. 25-13).

Figure 25-13. Algorithm for the approach to acute caustic injury. For the definitions of endoscopic grades of injury, see Table 25-3. EGD, esophagogastroduodenoscopy.

Given the fact that symptoms and the physical examination may not match the degree of injury after a caustic ingestion, an upper endoscopy examination should be performed in the first 24 to 48 hours after ingestion in patients without perforation.130 An upper endoscopy allows diagnosis of injury to the GI tract, permits grading of the degree of injury, establishes a prognosis, and can guide therapy (see Fig. 25-13). It is important to note that up to 40% to 80% of patients with a reported caustic ingestion will have no evidence of injury on endoscopic examination.131

The degree of injury seen on endoscopic examination can be graded and provides prognostic information (Table 25-3). Grades I and IIA burns, which correspond to first- and second-degree burns, will usually heal without sequelae.126 However, strictures will develop in 70% to 100% of patients with grade IIB injury, which causes circumferential ulceration, and grade III injury, with associated necrosis.132 Grade IV injury, with perforation, carries a mortality rate of up to 65% and requires urgent surgery.

| GRADE | ENDOSCOPIC FINDINGS |

|---|---|

| I | Edema and erythema |

| IIA | Hemorrhage, erosions, blisters, ulcers with exudate |

| IIB | Circumferential ulceration |

| III | Multiple deep ulcers with brown, black, or gray discoloration |

| IV | Perforation |

TREATMENT

Emergency surgery is required with esophagectomy or gastrectomy for perforation. Colonic interposition is sometimes required. Operator and institutional experience affects mortality and morbidity of emergent esophagogastrectomy and is best undertaken at referral centers when circumstances allow.133

The need for and timing of operative intervention in patients with severe ulceration or necrosis without clear evidence of perforation remains controversial. Comparative analyses are difficult in this patient population. Some authorities have suggested that early operative exploration decreases mortality,134 but others cite lower mortality rates and complete healing in patients with nonoperative supportive care.127 As such, management must be considered on an individualized basis.

Inducing emesis or placing a nasogastric tube to clear or dilute the GI tract of the caustic agent is contraindicated because it may re-expose the esophagus, oropharynx, and airway to the caustic agent. Induced retching and vomiting may increase the risk of perforation. The use of neutralizing agents is not recommended because they have not been shown to be efficacious, may lead to increased thermal injury, and may also promote retching and emesis.135 In addition, the routine use of glucocorticoids124 and systemic antibiotics122 is not recommended.

LATE COMPLICATIONS

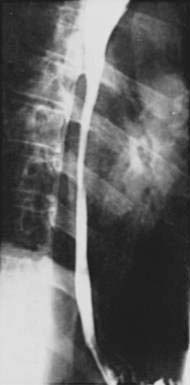

Up to one third of caustic ingestion patients will develop esophageal stricture after initial recovery (see Fig. 25-11). Stricture formation presents most commonly at two months after injury but can occur at any time from two weeks to many years after the initial injury.126 Stricture formation occurs more commonly following more severe (grade IIB or III) injuries (see Table 25-3). The primary treatment of esophageal strictures secondary to caustic ingestion is frequent dilation. Endoscopic management of caustic strictures must be deliberate, with gradual and incremental progressive dilation to 15 mm or until symptom relief is obtained.136 The perforation rate is 0.5% for endoscopic dilation of chronic caustic strictures and as many as 10% to 50% of patients will eventually require operative intervention. Esophageal resection with an esophagogastric anastomosis, esophagojejunostomy, or colonic interposition may be considered.137 Case reports have described successful treatment with the use of temporary esophageal stents soon after caustic ingestion, but there is insufficient evidence to support recommendations for routine prophylactic stenting or for prophylactic early endoscopic dilation to prevent caustic-related strictures.135

Antral and pyloric strictures may also occur after caustic injury (Fig. 25-14). Antral and pyloric stenoses will usually develop one to six weeks after caustic ingestion, but can also occur years later.122 The risk of antral stenosis is also related to the degree of injury. Endoscopic dilation with the addition of acid suppression is successful in many patients, but many others will require antrectomy.

Figure 25-14. Barium radiograph of a chronic antral stricture caused by a caustic ingestion.

(Courtesy of Dr. Robert N. Berk, San Diego, Calif.)

Alkaline caustic ingestion, in particular, is associated with an increased risk for squamous cell cancer of the esophagus. Patients with a history of lye ingestion have a 1000-fold increased risk of developing esophageal cancer, with a lag time from injury of approximately 40 years.138 Periodic endoscopic surveillance is advocated every one to three years, beginning 20 years after the caustic ingestion.

Figure 25-15 summarizes the time course of complications from caustic ingestions reviewed in this section.

Alzakem AM, Soundappan SSV, Jefferies H, et al. Ingested magnets and gastrointestinal complications. J Pediatr Child Health. 2007;40:497-8. (Ref 102.)

Clarke DL, Buccimazza I, Anderson FA, et al. Colorectal foreign bodies. Colorectal Dis. 2005;7:98-103. (Ref 32.)

Gmeiner D, von Rahden BHA, Meco C, et al. Flexible versus rigid endoscopy for treatment of foreign body impaction in the esophagus. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:2026-29. (Ref 81.)

Harikumar R, Humar S, Kumar B, et al. Rapunzel syndrome: A case report and review of literature. Tropical Gastroenterol. 2007;28:37-8. (Ref 118.)

Kerlin P, Jones D, Remedios M, et al. Prevalence of eosinophillic esophagitis in adults with food bolus obstruction of the esophagus. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;41:356-61. (Ref 26.)

Lake JP, Essani R, Petrone P, et al. Management of retained colorectal foreign bodies: Predictors of operative intervention. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:1694-8. (Ref 110.)

Lin HH, Lee SC, Chu HC, et al. Emergency endoscopic management of dietary foreign bodies in the esophagus. Am J Emerg Med. 2007;25:662-5. (Ref 28.)

Morrissey SK, Thakar SJ, Weaver ML, Farah K. Bread bag clip ingestion: A rare cause of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;4:499-500. (Ref 104.)

Rodriguez-Hermosa JI, Codina-Cazador A, Sirvent JM, et al. Surgically treated perforations of the gastrointestinal tract caused by ingested foreign bodies. Colorectal Dis. 2008;10:701-7. (Ref 94.)

Weissberg D, Refaely Y. Foreign bodies in the esophagus. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;84:1854-7. (Ref 83.)

Wong KKY, Fang CX, Tam PHK. Selective upper endoscopy for foreign body ingestion in children: An evaluation of management protocol after 282 cases. J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41:2016-18. (Ref 63.)

Zhou JH, Jiang YG, Wang RW, et al. Management of corrosive esophageal burns in 149 cases. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;130:449-55. (Ref 133.)

1. Eisen GM, Baron TH, Dominitz JA, et al. Guideline for the management of ingested foreign bodies. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:802-6.

2. Clerf LH. Historical aspects of foreign bodies in the food and air passages. South Med J. 1975;68:1449-54.

3. Devanesan J, Pisani A, Sharman P, et al. Metallic foreign bodies in the stomach. Arch Surg. 1977;112:664-5.

4. Lyons MF, Tsuchida AM. Foreign bodies of the gastrointestinal tract. Med Clin North Am. 1993;77:1101-14.

5. Webb WA. Management of foreign bodies of the upper gastrointestinal tract: Update. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;41:39-51.

6. Cheng W, Tam PKH. Foreign-body ingestion in children: Experience with 1265 cases. J Pediatr Surg. 1999;34:1472-6.

7. Chu KM, Choi HK, Tuen HH, et al. A prospective randomized trial comparing the use of the flexible gastroscope versus the bronchoscope in the management of foreign body ingestion. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;47:23-7.

8. Velitchkov NG, Grigorov GI, Losanoff JE, et al. Ingested foreign bodies of the gastrointestinal tract. Retrospective analysis of 542 cases. World J Surg. 1996;20:1001-5.

9. Kim JK, Kim SS, Kim JI, et al. Management of foreign bodies in the gastrointestinal tract: An analysis of 104 cases in children. Endoscopy. 1999;31:301-4.

10. Hachimi-Idrissi S, Corne L, Vandenplas Y. Management of ingested foreign bodies in childhood: Our experience and review of the literature. Eur J Emerg Med. 1998;5:319-23.

11. Paneiri E, Bass DH. The management of ingested foreign bodies in children—a review of 663 cases. Eur J Emerg Med. 1995;2:83-7.

12. Tokar B, Cevik A, Ihan H. Ingested gastrointestinal foreign bodies: Predisposing factors for complications in children having surgical or endoscopic removal. Pediatr Surg Int. 2007;23:135-9.

13. Simic MA, Budakov BM. Fatal upper esophageal hemorrhage caused by a previously ingested chicken bone: Case report. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 1998;19:166-8.

14. Bennett DR, Baird CJ, Chan KM, et al. Zinc toxicity following massive coin ingestion. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 1997;18:148-53.

15. Chen MK, Beierle EA. Gastrointestinal foreign bodies. Pediatr Ann. 2001;30:736-42.

16. O’Brien GC, Winter DC, Kirwan WO, et al. Ingested foreign bodies in the paediatric patient. Ir J Med Sci. 2001;170:100-2.

17. Smith MT, Wong RKH. Foreign bodies. Gastrointest Endoscopy Clin N Am. 2007;17:361-82.

18. Al-Wahadni A, Al Hamad KQ, Al-Tarawneh A. Foreign body ingestion and aspiration in dentistry: A review of the literature and reports of three cases. Dent Update. 2006;33:561-70.

19. Gluck M. Coin ingestion complicating a tavern game. West J Med. 1989;150:343-44.

20. O’Sullivan ST, McGreal GT, Reardon CM, et al. Selective endoscopy in management of ingested foreign bodies of the upper gastrointestinal tract: Is it safe? Int J Clin Pract. 1997;51:289-92.

21. Perez Segura P, Siso I, Luque R, et al. Iatrogenic intestinal obstruction: A rare complication of capsule endoscopy in a patient with familial adenomatous polyposis. Endoscopy. 2007;39(Suppl 1):E298-9.

22. Lattuneddu A, Farneti F, Lucci E, et al. Small bowel perforation after incomplete removal of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy catheter. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:2028-31.

23. Longstreth GF, Longstreth KJ, Yao JF. Esophageal food impaction: Epidemiology and therapy. A retrospective, observational study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:193-8.

24. Vicari JJ, Johanson JF, Frakes JT. Outcomes of acute esophageal food impaction: Success of the push technique. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:178-81.

25. Lacy PD, Donnelly MJ, McGrath JP, et al. Acute food bolus impaction: Aetiology and management. J Laryngol Otol. 1997;111:1158-61.

26. Kerlin P, Jones D, Remedios M, et al. Prevalence of eosinophillic esophagitis in adults with food bolus obstruction of the esophagus. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;41:356-61.

27. Weinstock LB, Shatz BA, Thyssen EP. Esophageal food bolus obstruction: Evaluation of extraction and modified push technique in 75 cases. Endoscopy. 1999;31:421-5.

28. Lin HH, Lee SC, Chu HC, et al. Emergency endoscopic management of dietary foreign bodies in the esophagus. Am J Emerg Med. 2007;25:662-5.

29. Lim CT, Quah RF, Loh LE. A prospective study of ingested foreign bodies in Singapore. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1994;120:96-101.

30. Busch DB, Starling JR. Rectal foreign bodies: Case reports and a comprehensive review of the world’s literature. Surgery. 1986;100:512-19.

31. Ruiz del Castillo J, Selles Dechent R, Millan Scheiding M, et al. Colorectal trauma caused by foreign bodies introduced through sexual activity: diagnosis and management. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2001;93:631-4.

32. Clarke DL, Buccimazza I, Anderson FA, et al. Colorectal foreign bodies. Colorectal Dis. 2005;7:98-103.

33. Schwartz GF, Polsky HS. Ingested foreign bodies of the gastrointestinal tract. Am Surg. 1976;42:236-8.

34. Vizcarrondo FJ, Brady PG, Nord HJ. Foreign bodies of the upper gastrointestinal tract. Gastrointest Endosc. 1983;29:208-10.

35. Ginsberg GG. Management of ingested foreign objects and food bolus impactions. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;41:33-8.

36. Stack LB, Munter DW. Foreign bodies in the gastrointestinal tract. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 1996;14:493-521.

37. O’Flynn P, Simp R. Fish bones and other foreign bodies. Clin Otolaryngol. 1993;18:231-33.

38. Bloom RR, Nakano PH, Gray SW, et al. Foreign bodies of the gastrointestinal tract. Am Surg. 1986;10:618-21.

39. Potter JW, Saeian K, Staff D, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis in adults: An emerging problem with unique esophageal features. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:355-61.

40. Desai TK, Stecevic V, Chang CH, et al. Association of eosinophillic inflammation with esophageal food impaction in adults. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:795-801.

41. Stein HJ, Schwizer W, DeMeester TR, et al. Foreign body entrapment in the esophagus of healthy subjects—a manometric and scintigraphic study. Dysphagia. 1992;7:220-5.

42. Tibbling L, Bjorkhoel A, Jansson E, et al. Effect of spasmolytic drugs on esophageal foreign bodies. Dysphagia. 1995;10:126-7.

43. McCord GS, Staiano A, Clouse RE. Achalasia, diffuse spasm, and non-specific motor disorders. Baillieres Clin Gastroenterol. 1991;5:307-35.

44. Rohl L, Aksglaede K, Funch-Jensen P, et al. Esophageal rings and strictures: Manometric characteristics in patients with food impaction. Acta Radiol. 2000;41:275-9.

45. Brady P. Esophageal foreign bodies. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1991;20:691-701.

46. Scher R, Tegtmeyer C, McLean W. Vascular injury following foreign body perforation of the esophagus. Review of the literature and report of a case. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1990;99:698-702.

47. Davidhoff E, Towne JB. Ingested foreign bodies. N Y State Med J. 1975;75:1003-7.

48. Ginsberg GG, Barkun AN, Bosco JJ, et al. Wireless capsule endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:621-4.

49. Connolly AA, Birchall M, Walsh-Waring GP, et al. Ingested foreign bodies: Patient-guided localization is a useful clinical tool. Clin Otolaryngol. 1992;17:520-4.

50. Muniz AE, Joffe MD. Foreign bodies, ingested and inhaled. JAAPA. 1999;12:23-46.

51. Herranz-Gonzalez J, Martinez-Vidal J, Garcia-Sarandeses A, et al. Esophageal foreign bodies in adults. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1991;105:649-54.

52. Lee J. Bezoars and foreign bodies of the stomach. Gastrointest Endosc Clin North Am. 1996;6:605-19.

53. Webb WA, Taylor MB. Foreign bodies of the upper gastrointestinal tract. In: Taylor MB, editor. Gastrointestinal Emergencies. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1996:204.

54. Shaffer HA, de Lange EE. Gastrointestinal foreign bodies and strictures: Radiologic interventions. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 1994;23:205-49.

55. Ciriza C, Garcia L, Suarez P, et al. What predictive parameters best indicate the need for emergent gastrointestinal endoscopy after foreign body ingestion? J Clin Gastroenterol. 2000;31:23-8.

56. Gooden EA, Forte V, Papsin B. Use of a commercially available metal detector for the localization of metallic foreign body ingestion in children. J Otolaryngol. 2000;29:218-20.

57. Mosca S, Manes G, Martino L, et al. Endoscopic management of foreign bodies in the upper gastrointestinal tract: Report on a series of 414 adult patients. Endoscopy. 2001;33:692-6.

58. Mosca S. Management and endoscopic techniques in cases of ingestion of foreign bodies. Endoscopy. 2000;32:232-3.

59. Takada M, Kashiwagi R, Sakane M, et al. 3D-CT diagnosis for ingested foreign bodies. Am J Emerg Med. 2000;18:192-3.

60. Silva RG, Ahluwaiia JP. Asymptomatic esophageal perforation after foreign body ingestion. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:615-19.

61. Weiland ST, Schurr MJ. Conservative management of ingested foreign bodies. J Gastrointest Surg. 2002;6:496-500.

62. Kurkciyan I, Frossard M, Kettenbach J, et al. Conservative management of foreign bodies in the gastrointestinal tract. Z Gastroenterol. 1996;34:173-7.

63. Wong KKY, Fang CX, Tam PHK. Selective upper endoscopy for foreign body ingestion in children: An evaluation of management protocol after 282 cases. J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41:2016-18.

64. Alaradi O, Bartholomew M, Barkin JS. Upper endoscopy and glucagon: A new technique in the management of acute esophageal food impaction. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:912-13.

65. Colon V, Grade A, Pullman G, et al. Effect of doses of glucagon used to treat food impaction on esophageal motor function of normal subjects. Dysphagia. 1999;14:27-30.

66. Al-Haddad M, Ward EM. Glucagon for the relief of esophageal food impaction: Does it really work? Dig Dis Sci. 2006;51:1930-3.

67. Ferrucci JT, Long LA. Radiologic treatment of esophageal food impaction using intravenous glucagon. Radiology. 1977;125:25-8.

68. Trenker SW, Maglinte DT, Lehman G, et al. Esophageal food impaction: Treatment with glucagon. Radiology. 1983;149:401-3.

69. Rice BT, Spiegel PK, Dombrowski PJ. Acute esophageal food impaction treated by gas-forming agents. Radiology. 1983;146:299-301.

70. Smith JC, Janower ML, Geiger AH. Use of glucagon and gas-forming agents in acute esophageal food impaction. Radiology. 1986;159:567-8.

71. Maini S, Rudralingam M, Zeitoun H, et al. Aspiration pneumonitis following papain enzyme treatment for oesophageal meat imapaction. J Laryngol Otol. 2001;115:585-6.

72. Litovitz T, Scmitz BF. Ingestion of cylindrical and button batteries: An analysis of 2382 cases. Pediatrics. 1992;89:747-57.

73. Shaffer HA, de Lange EE. Gastrointestinal foreign bodies and strictures: Radiologic interventions. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 1994;23:205-49.

74. Schunk JE, Harrison AM, Corneli HM, et al. Fluoroscopic Foley catheter removal of esophageal foreign bodies in children: Experience with 415 cases. Pediatrics. 1994;94:709-14.

75. Katsinelos P, Kountouras J, Paroutoglou G, et al. Endoscopic techniques and management of foreign body ingestion and food bolus impaction in the upper gastrointestinal tract: A retrospective analysis of 139 cases. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40:784-9.

76. Conway WC, Sugawa C, Ono H, et al. Upper GI foreign body: An adult urban emergency hospital experience. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:455-60.

77. Khurana AK, Saraya A, Jain N, et al. Management of foreign bodies of the upper gastrointestinal tract. Trop Gastroenterol. 1998;19:32-3.

78. Vizcarrondo FJ, Brady PG, Nord HJ. Foreign bodies of the upper gastrointestinal tract. Gastrointest Endosc. 1983;29:208-10.

79. Henderson CT, Engel J, Schlesinger P. Foreign body ingestion: Review and suggested guidelines for management. Endoscopy. 1987;19:68-71.

80. Macgregor D, Ferguson J. Foreign body ingestion in children: An audit of transit time. J Accid Emerg Med. 1998;15:371-3.

81. Gmeiner D, von Rahden BHA, Meco C, et al. Flexible versus rigid endoscopy for treatment of foreign body impaction in the esophagus. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:2026-9.

82. Chu KM, Choi HK, Tuen HH, et al. A prospective randomized trial comparing the use of the flexible gastroscope versus the bronchoscope in the management of foreign body ingestion. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;47:23-7.

83. Weissberg D, Refaely Y. Foreign bodies in the esophagus. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;84:1854-7.

84. Nelson DB, Bosco JJ, Curtis WD, et al. ASGE technology status evaluation report. Endoscopic retrieval devices. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:932-4.

85. Bertoni G, Pacchione Sassatelli R, et al. A new protector device for safe endoscopic removal of sharp gastroesophageal foreign bodies in infants. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1993;16:393-6.

86. Bertoni G, Sassatelli R, Conigliaro R, et al. A simple latex protector hood for safe endoscopic removal of sharp-pointed gastroesophageal foreign bodies. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;44:458-61.

87. Faigel DO, Stotland BR, Kochman ML, et al. Device choice and experience level in endoscopic foreign object retrieval: An in vivo study. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;45:490-2.

88. Chaves DM, Ishioka S, Felix VN, et al. Removal of a foreign body from the upper gastrointestinal tract with a flexible endoscope: A prospective study. Endoscopy. 2004;36:887-92.

89. Gluck M, Schembre DB, Kozarek RA. A concern with the use of the push technique in patients with multiple esophageal rings. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:178-81.

90. Neustater B, Barkin JS. Extraction of an esophageal food impaction with a Roth retrieval net. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;43:66-7.

91. Mamel JJ, Weiss D, Pouagare M, et al. Endoscopic suction removal of food boluses from the upper gastrointestinal tract using Steigmann-Goff friction fit adapter. An improved method for removal of food impactions. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;41:593-6.

92. Pezzi JS, Shiau YF. A method for removing meat impactions from the esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc. 1994;40:634-6.

93. Byrne WJ. Foreign bodies, bezoars, and caustic ingestion. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 1994;4:99-119.

94. Rodriguez-Hermosa JI, Codina-Cazador A, Sirvent JM, et al. Surgically treated perforations of the gastrointestinal tract caused by ingested foreign bodies. Colorectal Dis. 2008;10:701-7.

95. Jackson C, Jackson CL. Diseases of the air and food passages of foreign body origin. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1937.

96. Kao LS, Nguyen T, Dominitz J, et al. Modification of a latex glove for the safe endoscopic removal of a sharp gastric foreign body. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:127-9.

97. Stringer MD, Capps SN. Rationalizing the management of swallowed coins in children. BMJ. 1991;302:1321-2.

98. Rebhandl W, Milassin A, Brunner L, et al. In vitro study of ingested coins: Leave them or retrieve them? J Pediatr Surg. 2007;42:1729-34.

99. Temple AR, Veltri JC. One year’s experience in a regional poison control center. The Intermountain Regional Poison Control Center. Clin Toxicol. 1978;12:27-89.

100. Litovitz TL. Button battery ingestions. JAMA. 1983;249:2495-500.

101. Litovitz TL, Schmitz BF. Ingestion of cylindrical and button batteries. An analysis of 2382 cases. Pediatrics. 1992;89:747-57.

102. Alzakem AM, Soundappan SSV, Jefferies H, et al. Ingested magnets and gastrointestinal complications. J Pediatr Child Health. 2007;40:497-8.

103. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Gastrointestinal injuries from magnet ingestion in children—United States, 2003-2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006:1296-300.

104. Morrissey SK, Thakar SJ, Weaver ML, Farah K. Bread bag clip ingestion: A rare cause of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;4:499-500.

105. Sporer KA, Firestone J. Clinical course of crack cocaine body stuffers. Ann Emerg Med. 1997;29:596-601.

106. Pidoto RR, Agliata AM, Bertolini R, et al. A new method of packaging cocaine for international traffic and implication for the management of cocaine body packers. J Emerg Med. 2002;23:149-53.

107. June R, Aks SE, Keys N, et al. Medical outcome of cocaine body stuffers. J Emerg Med. 2000;18:221-4.

108. Cohen JS, Sackuer JM. Management of colorectal foreign bodies. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1996;41:312-15.

109. Kourkalalis G, Misiajos E, Dovas N, et al. Management of foreign bodies of the rectum: Report of 21 cases. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1997;42:246-7.

110. Lake JP, Essani R, Petrone P, et al. Management of retained colorectal foreign bodies: Predictors of operative intervention. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:1694-8.

111. Andrus CH, Ponsky JL. Bezoars: Classification, pathophysiology, and treatment. Am J Gastroenterol. 1988;83:476-8.

112. Phillips MR, Zaheer S, Drugas GT. Gastric trichobezoar: Case report and literature review. Mayo Clin Proc. 1998;73:653-6.

113. Taylor JR, Streetman DS, Castle SS. Medication bezoars: A literature review and a report of a case. Ann Pharmacother. 1998;32:940-6. 1998

114. Escamilla C, Robles R, Campos R, Parilla-Paricio P, et al. Intestinal obstruction and bezoars. J Am Coll Surg. 1994;179:1691-3.

115. Dietrich NA, Gau FC. Postgastrectomy phytobezoars: Endoscopic diagnosis and treatment. Arch Surg. 1985;120:432-5.

116. Lee J. Bezoars and foreign bezoars of the stomach. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 1996;6:605-19.

117. Quraishi AHM, Kamath BS. Rapunzel syndrome. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:611.

118. Harikumar R, Humar S, Kumar B, et al. Rapunzel syndrome: A case report and review of literature. Tropical Gastroenterol. 2007;28:37-8.

119. Kuo JY, Mo LR, Tsai CC, et al. Nonoperative treatment of gastric bezoars using electrohydraulic lithotripsy. Endoscopy. 1999;31:386-8.

120. Klamer TW, Max MH. Recurrent gastric bezoars: A new approach to treatment and prevention. Am J Surg. 1983;145:417-19.

121. Wang YG, Seitz U, Li L, et al. Endoscopic management of huge bezoars. Endoscopy. 1998;30:371-4.

122. Kikendall JW. Caustic ingestion injuries. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1991;20:847-57.

123. Watson WA, Litovitz TL, Rodgers GCJr, et al. 2002 annual report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers Toxic Exposure Surveillance System. Am J Emerg Med. 2003;21:353-421.

124. Leape LL, Ashcraft KW, Carpelli DG, et al. Hazard to health: Liquid lye. N Engl J Med. 1971;284:578-81.

125. Gumaste VV, Dave PB. Ingestion of corrosive substances by adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87:1-5.

126. Zargar SA, Kochlar R, Nagi B, et al. Ingestion of corrosive alkalis. Spectrum of injury to upper gastrointestinal tract and natural history. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87:337-41.

127. Cello JP, Fogel RP, Boland R. Liquid caustic ingestion spectrum of injury. Arch Intern Med. 1980;140:501-4.

128. Gaudreault P, Parent M, McQuigan MA, et al. Predictability of esophageal injury from signs and symptoms: A study of caustic ingestions in 378 children. Pediatrics. 1983;71:767-70.

129. Lovejoy FH, Woolf AD. Corrosive ingestions. Pediatr Rev. 1995;16:473-4.

130. Poley JW, Steyerberg EW, Kuipers EJ, et al. Ingestion of acid and alkaline agents: Outcome and prognostic value of early upper endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:372-7.

131. Bautista Casasnovas A, Estevez Martinez E, Varela Cives R, et al. A retrospective analysis of ingestion of caustic substances by children. Ten-year statistics in Galicia. Eur J Pediatr. 1997;156:410-14.

132. Anderson KD, Rouse TM, Randolph JG. A controlled trial of corticosteroids in children with corrosive injury of the esophagus. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:637-40.

133. Zhou JH, Jiang YG, Wang RW, et al. Management of corrosive esophageal burns in 149 cases. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;130:449-55.

134. Estrera A, Taylor W, Mills LJ, et al. Corrosive burns of the esophagus and stomach. A recommendation for an aggressive surgical approach. Ann Thorac Surg. 1986;41:276-83.

135. Kirsh MM, Peterson A, Brown JW, et al. treatment of caustic imjuries of the esophagus. A ten-year experience. Ann Surg. 1978;188:675-8.

136. Broor SL, Raju GS, Bore PP, et al. Long-term results of endoscopic dilation for treatment of corrosive esophageal strictures. Gut. 1993;34:1498-501.

137. Kukkady A, Pease PWB. Long-term dilation of caustic strictures of the oesophagus. Pediatr Surg Int. 2002;18:486-90.

138. Kochhar R, Sethy PK, Kochhar S, et al. Corrosive induced carcinoma of the esophagus: Report of three patients and review of the literature. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21:777-80.