88 Forearm Fractures

• The goal of treatment of forearm fractures is to restore length, correct angulation, and ideally, achieve normal function.

• Radiographs of the proximal and distal joints of patients with a forearm fracture should always be considered to rule out concurrent dislocations (i.e., Monteggia fracture).

Epidemiology

Injury is a leading cause of mortality, morbidity, and lost days of work. The annual health care cost of injuries exceeds $9.2 billion. Traumatic injuries result in more than 34 million emergency department (ED) visits each year.1 The highest rate of injuries occurs in persons between the ages of 15 and 24 years. Likewise, forearm fractures are commonly seen in young adults but have a bimodal distribution, with a second increased incidence in the elderly.2

Pathophysiology

The bones of the forearm consist of the radius and ulna. These two bones lie in parallel and are connected by joint capsules at the elbow and at the wrist, whereas the shafts are interlocked by a fibrous interosseus membrane.3 Most forearm fractures are caused by a sudden force, such as a fall on an outstretched arm. Because of the interlocking joint capsules, interosseus membrane, and contraction of the forearm muscles, multiple fractures, displaced fragments, and concurrent dislocations may be present. Alternatively, forearm fractures may be due to smaller repetitive injuries, which result in a stress fracture over time. Any pathophysiologic process that reduces the integrity of the bone, such as osteopenia, osteomyelitis, and bone metastasis, increases the likelihood of fracture, even with normal external stress.4

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Symptoms of forearm fractures include pain, forearm edema, forearm ecchymosis, abnormal or reduced mobility from the wrist through the elbow, and complaints of neurovascular compromise. Findings on physical examination can include obvious bony deformity; shortening of the forearm; crepitus; tenderness to palpation of the forearm; joint effusions; abnormal mobility of the wrist, forearm, or elbow; and neurologic and vascular deficits of the forearm, wrist, or hand. Box 88.1 lists the signs and symptoms of fractures and complications that indicate serious injury.

Box 88.1 Signs and Symptoms of Fractures and Complications That Suggest Serious Injury

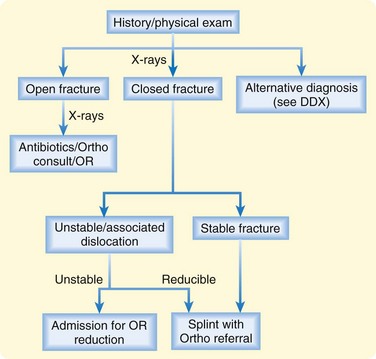

In general, forearm fractures are classified by the bone (or bones) involved, anatomic location, trajectory of the fracture and alignment of the fracture fragments, and the presence of angulation, rotation, comminution, and concurrent dislocations. All fractures should be further described as open or closed, and the presence (or absence) of distal neurologic and vascular function should be noted (Fig. 88.1).

Fig. 88.1 Approach to patients with a suspected forearm fracture.

DDX, Differential diagnosis; OR, operating room; Ortho, orthopedics.

Types of forearm fractures that are frequently mentioned in the medical literature are described in Table 88.1.

| NAME | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|

| Colles | Distal radial extension fracture (may also include the ulna) with dorsal displacement of the distal fragments |

| Smith | Distal radial flexion fracture with volar displacement of the distal fragments |

| Barton | Intraarticular fracture of the dorsal rim of the distal end of the radius, often associated with carpal dislocation. Treatment is typically operative |

| Hutchinson | Radial styloid fracture associated with carpal dislocation |

| Galeazzi | Distal radial shaft fracture with concurrent distal radioulnar dislocation |

| Monteggia | Ulnar shaft fracture with dislocation of the radial head |

Pediatric Fractures

Forearm fractures in the pediatric population include several additional entities because children have a plastic bone matrix and active growth plates, both of which contribute to unique fractures (Table 88.2). In children, when an external force bends a long bone, one side of the cortex may be disrupted while the other side remains intact (greenstick fracture). Alternatively, a deformity of the bone may occur without an obvious fracture line (plastic deformity). With compression, buckling of the cortex may be seen (torus fracture). Depending on the age of the child, fractures through the various growth plates of the elbow and wrist may also occur (Salter-Harris fractures).5

| NAME | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|

| Torus | Fracture involving compression buckling of one or both sides of the cortex |

| Greenstick | Fracture involving distraction of one side of the cortex without apparent disruption of the other |

| Plastic deformity | Bowing of the radius or ulna without obvious fracture lines (multiple microfractures) |

| Salter-Harris | Fracture involving the growth plates |

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

The differential diagnosis for forearm fractures includes any soft tissue injury to the forearm, in addition to acute skin, soft tissue, and joint infections (Box 88.2). Some clinical aspects of acute arterial occlusion, as well as venous thrombosis, may mimic forearm fractures. Any acute neurologic change, including paresthesias, weakness, and functional loss, should be considered along with forearm fractures. Two normal variants sometimes mistaken for forearm fractures on radiographs are normal growth plates in children and nutrient vessels.

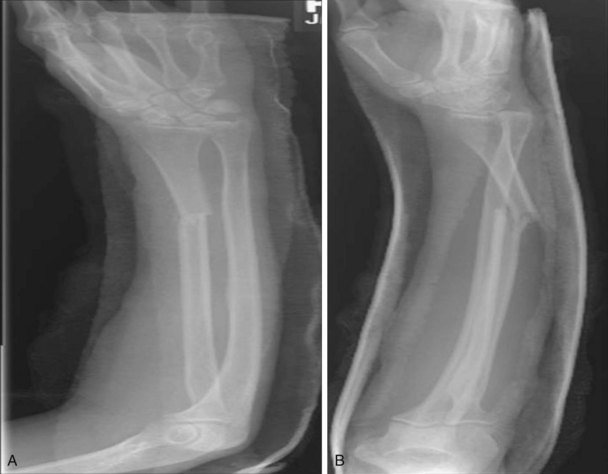

The orthopedic literature often recommends radiographs of a suspected fracture and additional films of the joints above and below the injury (Fig. 88.2; Table 88.3). This is true for forearm fractures if they are close to the joint (either elbow or wrist) or are suspected of having a concurrent dislocation (Fig. 88.3).

Table 88.3 Radiographs Useful in the Differential Diagnosis of Forearm Fractures

| SUSPECTED INJURY | VIEWS |

|---|---|

| Proximal forearm fracture | Elbow series (AP and lateral) and forearm series (AP and lateral forearm) |

| Shaft fracture | Forearm series |

| Distal forearm fracture | Wrist series (AP and lateral wrist) and forearm series |

AP, Anteroposterior.

Additional films are not usually necessary with uncomplicated shaft fractures (one bone, nondisplaced). If the fracture is intraarticular, additional radiographic views or computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging may be suggested (Table 88.4).

Table 88.4 Special Circumstances in the Differential Diagnosis of Forearm Fractures

| SUSPECTED INJURY | ADDITIONAL RADIOLOGY |

|---|---|

| Proximal forearm fracture—olecranon | Elbow series (AP and lateral) with the elbow in 90 degrees of flexion; forearm series (AP and lateral) |

| Proximal forearm fracture—radial head and neck | Elbow series, including oblique views, if the coronoid process is involved; forearm series |

| Fracture of the distal end of the forearm | If the radiocarpal or radioulnar joint is involved, CT or MRI to define subluxation or dislocation |

AP, Anteroposterior; CT, computed tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

Although most forearm fractures are evident on plain radiographs, occult fractures of the elbow may be difficult to interpret. One indication of an elbow fracture is the fat pad or sail sign, which indicates hemarthrosis of the elbow joint and thus a fracture.6

Treatment

Prehospital treatment includes immobilization to reduce the development of further injury and help control pain. The mainstays of ED treatment include pain control, reduction of further injury, immobilization, and appropriate disposition.7 Pain control should include elevation of the arm and cooling via ice packs. Oral or parenteral pain medications are usually indicated, depending on the age and size of the patient and the amount of pain.

Reduction of further injury depends on the fracture. Patients with open fractures and suspected open fractures should be given early parenteral antibiotic therapy and tetanus prophylaxis (if indicated). Displaced fractures and fractures with associated dislocations require early relocation, either by the emergency physician in consultation with an orthopedic surgeon or, if the patient’s condition is unstable, by an orthopedic surgeon in the ED.8

Tips and Tricks

Splinting Procedure

Use extra padding on the elbow and wrist.

Cast padding should be smooth to avoid pressure points.

To avoid irregularities, use constant pressure (palms, not fingers) to shape the splint.

Always repeat the distal neurovascular examination after the splint dries.

If in doubt, splint joints in the position of use and avoid flexion contractures.

The preferred method of fracture immobilization in the ED is splinting rather than casting because fracture edema will tend to increase in size over the first 24 hours. Specific splints for particular fractures are listed in Table 88.5.

| FRACTURE | IMMOBILIZATION |

|---|---|

| Proximal forearm fracture (olecranon and radial head and neck) | Long arm posterior splint |

| Shaft fracture without displacement | Long arm posterior splint |

| Shaft fracture with displacement | Long arm posterior splint with urgent orthopedic referral for surgical reduction |

| Shaft fracture with concurrent dislocations | Reduction and long arm posterior splint |

| Distal fracture—Colles, Smith, shaft | Reduction in the emergency department and sugar-tong splint |

| Hutchinson | Short dorsal forearm splint (reduction) |

| Barton | Short volar forearm splint (reduction) |

Follow-Up, Next Steps in Care, and Patient Education

Patients with forearm fractures can be classified into three categories: those who need immobilization with routine orthopedic follow-up, those who need interventions in the ED with very close follow-up, and those who should be admitted to the hospital.9

![]() Priority Actions

Priority Actions

History: Elucidate mechanisms with a high potential for open fractures.

Physical examination: Check the joints above and below the injury, examine the skin for open wounds, and evaluate and reevaluate neurovascular status distal to the injury.

Radiography: Always look for a second fracture or associated dislocation.

Treatment: Antibiotic therapy is needed for patients with open fractures; early reduction of dislocations and displaced fractures is essential.

![]() Documentation

Documentation

History

![]() Patient Teaching Tips

Patient Teaching Tips

Recovery from orthopedic injuries takes time and often involves extensive rehabilitation.

Provide a cast or splint care instruction sheet; for example, “Don’t get it wet.”

Inform the patient about the side effects of pain control medication.

Educate the patient about warning signs for which to seek immediate care—for example, increased pain, cold fingers, or loss of mobility.

Blakeney WG. Stabilization and treatment of Colles’ fractures in elderly patients. Clin Interv Aging. 2010;5:337–344.

Cheng JC, Shen WY. Limb fracture pattern in different pediatric age groups: a study of 3,350 children. J Orthop Trauma. 1993;7:15–22.

Handoll HH, Madhok R. Closed reduction methods for treating distal radial fractures in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 1, 2003. CD003763

Morgan WJ, Breen TF. Complex fractures of the forearm. Hand Clin. 1994;10:375–390.

Simon R, Koenigsknecht S. Fractures of the radius and ulna. In Emergency orthopedics: the extremities, 4th ed, New York: McGraw-Hill; 2001:195–230.

1 Advance Data from Vital and Health Statistics. No. 248. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 1992. Center for Disease Control National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). Monitoring Health Care in America Quarterly Fact Sheet, September 1995.

2 Owen RA, Melton 3rd, LJ., Johnson KA, et al. Incidence of Colles’ fracture in a North American community. Am J Public Health. 1982;72:605–607.

3 Blakeney WG. Stabilization and treatment of Colles’ fractures in elderly patients. Clin Interv Aging. 2010;5:337–344.

4 Simon R, Koenigsknecht S. Fractures of the radius and ulna. In Emergency orthopedics: the extremities, 4th ed, New York: McGraw-Hill; 2001:195–230.

5 Cheng JC, Shen WY. Limb fracture pattern in different pediatric age groups: a study of 3,350 children. J Orthop Trauma. 1993;7:15–22.

6 Norell HG. Roentgenologic visualization of the extracapsular fat: its importance in the diagnosis of traumatic injuries to the elbow. Acta Radiol. 1954;42:205–210.

7 Handoll HH, Madhok R. Closed reduction methods for treating distal radial fractures in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 1, 2003. CD003763

8 Macule Beneyto F, Arandes Renu JM, Ferreres Claramunt A, et al. Treatment of Galeazzi fracture-dislocations. J Trauma. 1994;36:352–355.

9 Morgan WJ, Breen TF. Complex fractures of the forearm. Hand Clin. 1994;10:375–390.