183 Food- and Water-Borne Infections

• In patients who develop clinical illness from food-borne and water-borne pathogens, most symptoms resolve spontaneously without intervention.

• Significant mortality does occur. Each year, thousands of people in the United States and millions of people in developing countries die of acute gastroenteritis.1

• Proper treatment can lead to significant relief for the patient, but inappropriate medications may complicate the clinical picture, lengthen the carrier state, or trigger potentially life-threatening conditions.

• Developing a systematic approach to gastrointestinal disease is essential to eliminate unnecessary testing and to restore health as quickly as possible while minimizing adverse and dangerous effects of intervention.

Pathophysiology

Infections of the small intestine may disrupt ionic exchange and result in increased chloride secretion and sodium retention within the bowel lumen. Water follows, thereby overwhelming absorption capacity, and diarrhea ensues. Viruses create diarrhea by distorting the epithelium and interfering with absorptive capabilities. This process results in loss of fluid, electrolytes, and, in some cases, fats and sugars. Because of the high secretory capabilities of the small intestine, infection of this region can lead to large-volume, watery diarrhea. In patients with large fluid losses, significant electrolyte disturbances and acidosis may occur, more commonly with infections of the small intestine.2 Given the predominant location of the small intestine, cramping and discomfort are localized more often to the upper abdomen.

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Although food containing preformed toxins can cause illness within 1 to 6 hours, most acute gastroenteritis has at least a 12- to 48-hour incubation period (Table 183.1). Typically, the onset is gradual and is often noticed as mild dyspepsia after eating a meal. This is the meal often suspected by the patient to be the cause of the illness. However, the pathogen has usually been incubating for the last 1 to 2 days and is just starting to cause symptoms.

| ORGANISM OR PATHOGEN | Symptom Onset |

|---|---|

| Scombroid fish (poisoning) | 5-60 min; average, 20-30 min |

| Staphylococcus | 1-6 hr |

| Bacillus cereus | 2-14 hr; average, 2-4 hr |

| Ciguatera fish (poisoning) | 2-6 hr, ≥24 hr |

| Clostridium perfringens enterotoxin | 6-24 hr |

| Vibrio parahaemolyticus | 4-48 hr; average, 8-12 hr |

| Salmonella | 8-48 hr |

| Shigella | 24-48 hr |

| Plesiomonas shigelloides | 24-48 hr |

| Cholera and noncholera Vibrio species | 24-48 hr |

| Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli | 24-72 hr |

| Norovirus or rotavirus | 24-72 hr |

| Campylobacter | 2-5 days |

| Yersinia | 1-14 days; average, 2-4 days |

| Aeromonas hydrophila | 1-5 days |

| Hemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 | 3-8 days |

| Cryptosporidium and Isospora | 5-10 days |

| Clostridium difficile | Days to month;, average, 5-14 days |

| Giardia | 1-3 wk |

| Entamoeba histolytica | 1 wk-1 yr |

Diarrhea can occur simultaneously with vomiting, or it may be delayed for up to 48 hours after vomiting begins. In some cases, diarrhea may be the only component of clinical illness. Gross diarrheal blood is more common than hematemesis and varies by pathogen (Box 183.1). Dysentery, defined as a diarrheal stool containing gross blood, can be accompanied by fever, abdominal pain, and tenesmus.

![]() Documentation

Documentation

History

• Ingestion of suspicious foods in last 7 days

• Exposure to people with similar symptoms

• Recent antibiotics or hospitalizations (consider Clostridium difficile)

• Pregnancy (increased risk of Listeria monocytogenes)

Differential Diagnosis

Vomiting and Diarrhea

Vomiting Without Diarrhea

Diagnostic Testing

Diagnostic testing is often overused in infectious gastroenteritis. With symptoms lasting less than 24 hours in otherwise healthy individuals who are not at the extremes of age, no diagnostic testing is indicated, other than a pregnancy test in women of reproductive age. Exceptions include patients with severe symptoms, multiple grossly bloody stools, or hemodynamic instability, as well as testing for epidemiologic purposes if food poisoning or a bioterrorism event is suspected.3,4

Although the diagnostic yield is generally low, stool culture in patients who have unrelenting diarrhea may detect a treatable cause that can significantly shorten the course of illness.5 Typically, positive results take at least 2 to 3 days, and symptoms have often resolved by the time results return. For patients who develop diarrhea 3 days or more after being hospitalized, bacterial stool cultures have not been found to be helpful.6 Testing for ova and parasites has not shown to be cost effective unless the patient is at identifiable risk. This group includes patients with diarrhea persisting for several days after international travel to endemic regions, persons who ingest untreated water while camping or hiking, those with exposure to daycare centers, men who have sexual contact with other men, and persons who have sexual contact with patients with AIDS.7 If parasitic infection is suspected, three separate specimens from different time periods must be sent for ova and parasites before the test can be considered negative. Clostridium difficile testing should be performed for anyone with persistent diarrhea and a history of antibiotic use in the previous 3 months. In patients with severe diarrhea, C. difficile testing should be considered even in the absence of recent antibiotic exposure or recent hospitalization. The reason is the emergence of a hypervirulent strain, designated NAP1/BI/O27, that has caused illness in otherwise healthy individuals without the traditional risk factors for C. difficile colitis.8

The recommended diagnostic work-up in patients with AIDS and in others who are severely immunocompromised is more aggressive. Studies in these patients tend to yield more positive results, and symptoms are less apt to resolve without intervention. Stool should be sent for culture just as in immunocompetent patients. C. difficile testing should be performed because this remains the most common pathogen detected in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection and diarrhea. Three separate specimens should be sent to be examined for ova and parasites, given the intermittent shedding of organisms. In addition, stool should be sent for acid-fast smear to detect Cryptosporidium, Isospora, and Cyclospora. Finally, in severely immunocompromised patients with a CD4 count lower than 100 cells/microliter, a trichrome stain should be ordered to test for microsporidium.9 Unlike in immunocompetent patients, in whom blood cultures are of extremely limited use, blood culture results in immunocompromised patients may be positive in up to 40% of cases and may yield a diagnosis even in the absence of positive stool culture results.10 Fungal blood cultures should also be considered, to detect Mycobacterium avium complex. In this population, if severe diarrhea persists despite negative evaluations, the patient will need endoscopic evaluation for mucosal biopsy and additional cultures.

In patients with an acute onset of vomiting and diarrhea, documentation of gross blood in the stool is helpful. Checking for occult blood has not been proven to be sensitive or specific. When gross blood is absent, hemoccult testing provides little to no insight into the causative pathogen and should not be used to guide treatment. Similarly, fecal leukocyte testing has low sensitivity and specificity and should not be used to justify empiric antibiotic treatment.11,12

Treatment and Disposition

For patients experiencing neurologic symptoms such as paresthesias, dysesthesias, reversal of hot and cold sensation, or even altered mental status after eating fish, ciguatera poisoning should be suspected. Although not universally accepted, mannitol, 1 g/kg of a 20% solution over 30 minutes, has dramatic effects on improving symptoms.13–15

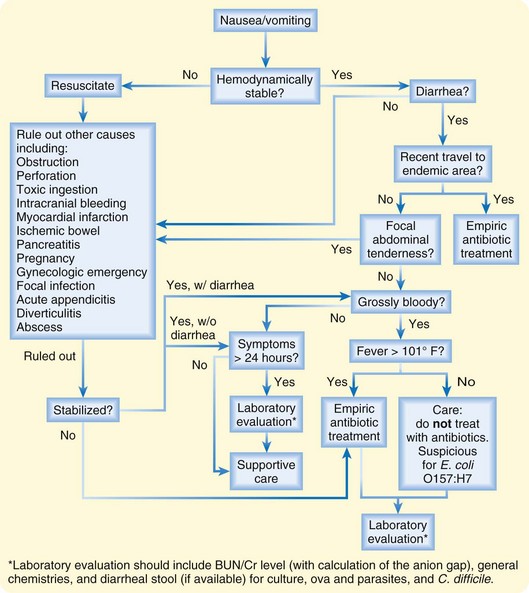

Most patients are stable, however, and are suffering from nausea, vomiting, crampy abdominal pain, and possibly diarrhea without other significant symptoms. For this group, the mainstays of treatment consist of rehydration and alleviation of symptoms through antiemetics (Fig. 183.1). The use of empiric antibiotics is not indicated in most cases.

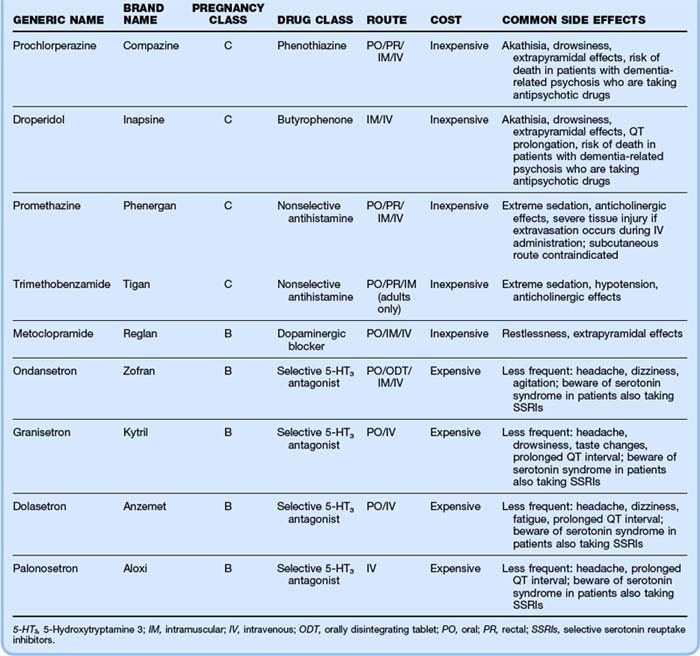

Many choices of antiemetics and routes of administration are available. When choosing a medication, one should consider pregnancy class, cost, and side effects, particularly the extrapyramidal side effects of the phenothiazines and metoclopramide. Table 183.2 gives the characteristics of common antiemetic agents. If one agent fails, a switch to a different class of agent is recommended, rather than repeat administration of an agent of the same class.

Another indication for empiric antibiotics involves acute gastroenteritis in the setting of travel to areas endemic for traveler’s diarrhea. The most common pathogens include enterotoxigenic E. coli, Shigella, Salmonella, and Campylobacter. In many cases, prompt use of a fluoroquinolone can lead to relief of symptoms within hours. Unfortunately, resistance to this class of drugs and to many other antibiotics is rising throughout the world, and treatment failures are becoming more common. Of the foregoing pathogens, Campylobacter has a high enough resistance to fluoroquinolones that erythromycin is now the drug of choice in these infections. For continued empiric treatment of traveler’s diarrhea in patients who do not respond to fluoroquinolones, azithromycin may be used. Sending stool cultures before the initiation of antibiotics can be helpful, given the high rates of resistance, in anticipation of potential treatment failures. Table 183.3 gives specific antibiotic regimens for symptomatic patients in whom the pathogen is identified.

| ORGANISM OR PATHOGEN | ANTIBIOTIC TREATMENT | COMMENT |

|---|---|---|

| Unknown (if empiric therapy deemed necessary) |

For inpatient treatment

Usually self-limited, efficacy of oral antibiotics unknown; susceptible to ampicillin and TMP-SMX

For suspected or known bacteremia, parenteral antibiotics required:

Ampicillin 2 g IV q4h with or without gentamicin (first week only) × 14 days

TMP-SMX 20 mg/kg/day of trimethoprim IV divided q6h × 14 days

or

Mebendazole 100 mg chewed × 1

or

Pyrantel pamoate 11 mg/kg (maximum, 1 g) × 1

Repeat dose × 1 in 2 wk

Repeat dose × 1 in 2 wk

bid, Twice daily; DS, double strength; IV, intravenously; PO, orally; qid, four times daily; tid, three times daily; TMP-SMX, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

From DuPont HL. Bacterial diarrhea. N Engl J Med 2009;361:1560-1569.

![]() Facts and Formulas

Facts and Formulas

Homemade Oral Rehydration Solution

The most common cause of acute gastroenteritis is viral.

Of bacterial causes, the three most common are Campylobacter, Salmonella, and Shigella.

Escherichia coli O157:H7 is more common in patients with grossly blood stools.

Nonbloody bacterial stool cultures are positive 1% to 5% of the time in immunocompetent adults.

Grossly bloody bacterial stool cultures are positive up to 20% of the time in immunocompetent adults.16

A pathogen can be identified in 80% to 85% of patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and diarrhea.17

Dietary recommendations are always of great concern to patients on discharge. Many complex regimens involve significant dietary restrictions, based on limited scientific data. Patients should be advised that the number-one priority is to stay hydrated. If solid foods do not sound appealing, then they should not be encouraged. For patients with mild diarrhea or persistent nausea, water or commercially available sports drinks should be adequate. These drinks are not properly balanced for more severe dehydration. If the patient is having large volumes of diarrhea or fluid losses, a balanced glucose and electrolyte solution with or without starches is recommended. Oral rehydration solutions are available in many pharmacies. An effective solution can be made at home by adding one-half teaspoon of salt, one-half teaspoon of baking soda, and four tablespoons of sugar to 1 L of water.18

![]() Patient Teaching Tips

Patient Teaching Tips

Diet

• Start drinking sips of liquids.

• If tolerated, advance to full liquids.

• Once hungry, eat small amounts of whatever sounds good, with the exception of alcohol and caffeine-containing foods and drinks because these may exacerbate the symptoms.

• If dairy products exacerbate symptoms, avoid for 1 to 2 weeks as a temporary measure because lactose intolerance is not uncommon.

Complications

Profound International Normalized Ratio Elevations in Patients Taking Warfarin

Case reports in patients taking warfarin have noted significant coagulopathies occurring in acute gastroenteritis. Although these disorders are usually associated with episodes lasting several days, one case occurred after a single day of diarrhea. The mechanism is presumed to be a decreased vitamin K level in the body, from both decreased oral intake and malabsorption within the intestine.19,20 Prothrombin time and international normalized ratio should be checked in patients taking warfarin, and close follow-up with repeat blood tests can prevent potential bleeding complications.

Neurologic Complications

Campylobacter has been associated with a more severe form of Guillain-Barré syndrome that occurs even in patients with asymptomatic infections who have no signs of gastroenteritis.21 Most neurologic symptoms from ciguatera poisoning resolve in days to weeks, but some long-term dysesthesias have been documented up to 2 years later.13 Shigella can cause seizures and other neurologic symptoms, especially in children.

Other Organ System Involvement

Although rare, invasive bacterial pathogens have been associated with systemic complications such as cholecystitis, pancreatitis, meningitis, endocarditis, and osteomyelitis.22 Patients suffering from amebic colitis resulting from E. histolytica can develop a hepatic abscess. Bacillus anthracis may cause a spectrum of illness from minimal symptoms to shallow oral ulcers, massive lymphadenopathy with tissue edema, and fulminant upper and lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Severe cases of C. difficile colitis have led to protein-losing enteropathy with ascites and peripheral edema.23

Cohen SH, Gerding DN, Johnson S, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults: 2010 update by the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) and the Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA). Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;21:1–25.

DuPont HL. Bacterial diarrhea. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1560–1569.

Fleckenstein JM, Bartels SR, Drevets PD, et al. Infectious agents of food- and water-borne illnesses. Am J Med Sci. 2010;340:238–246.

1 Mead PS, Slutsker L, Dietz V, et al. Food-related illness and death in the United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 1999;5:607–625.

2 Field M, Rao MC, Chang EB. Intestinal electrolyte transport and diarrheal disease. Part II. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:879–883.

3 Guerrant RL, Van Gilder T, Steiner TS, et al. Practice guidelines for the management of infectious diarrhea. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:331–351.

4 Thielman NM, Guerrant RL. Clinical practice: acute infectious diarrhea. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:38–47.

5 DuPont HL. Guidelines on acute infectious diarrhea in adults: the Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:1962–1975.

6 Rohner P, Pittet D, Pepey B, et al. Etiological agents of infectious diarrhea: implications for requests for microbial culture. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1427–1432.

7 Siegel D, Edelstein P, Nachamkin I. Inappropriate testing for diarrheal diseases in the hospital. JAMA. 1990;263:979–982.

8 Cohen SH, Gerding DN, Johnson S, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults: 2010 update by the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) and the Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA). Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;21:1–25.

9 Chioralia G, Trammer T, Kampen H, Seitz HM. Relevant criteria for detecting microsporidia in stool specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:2279.

10 Smith PD, Quinn TC, Strober W. NIH Conference: gastrointestinal infections in AIDS. Ann Intern Med. 1992;116:63–77.

11 Siegel D, Cohen PT, Neighbor M, et al. Predictive value of stool examination in acute diarrhea. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1987;111:715–718.

12 Herbert ME. Medical myth: measuring white blood cells in the stools is useful in the management of acute diarrhea. West J Med. 2000;172:414.

13 Friedman MA, Fleming LE, Fernandez M, et al. Ciguatera fish poisoning: treatment, prevention and management. Mar Drugs. 2008;6:456–479.

14 Schnorf H, Taurarii M, Cundy T. Ciguatera fish poisoning: a double-blind randomized trial of mannitol therapy. Neurology. 2002;58:873–880.

15 Palafox NA, Jain LG, Pinano AZ, et al. Successful treatment of ciguatera fish poisoning with intravenous mannitol. JAMA. 1988;259:2740–2742.

16 Musher DM, Musher BL. Contagious acute gastrointestinal infections. N Engl J Med. 2004;551:2417–2427.

17 Sanchez-Mejorada G, Ponce de Leon S. Clinical patterns of diarrhea in AIDS: etiology and prognosis. Rev Invest Clin. 1994;46:187–196.

18 de Zoysa I, Kirkwood B, Feachem R, Lindsay-Smith E. Preparation of sugar-salt solutions. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1984;78:260–262.

19 Smith JK, Aljazairi A, Fuller SH. INR elevation associated with diarrhea in a patient receiving warfarin. Ann Pharmacother. 1999;33:301–304.

20 Robert RJ, Rao P, Miske GR, et al. Diarrhea-associated over-anticoagulation in a patient taking warfarin: therapeutic role of cholestyramine. Vet Hum Toxicol. 2000;42:351–353.

21 Allos M. Campylobacter jejuni infections: update on emerging issues and trends. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:1201.

22 Fleckenstein JM, Bartels SR, Drevets PD, et al. Infectious agents of food- and water-borne illnesses. Am J Med Sci. 2010;340:238–246.

23 Dansinger ML, Johnson S, Jansen PC, et al. Protein-losing enteropathy is associated with Clostridium difficile diarrhea but not with asymptomatic colonization: a prospective, case-control study. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;22:932.

teaspoon salt

teaspoon salt teaspoon baking soda

teaspoon baking soda