18 Food allergies and intolerance

Case

A male aged 16 years presents complaining of abdominal bloating and diarrhoea for 1 month. This commenced following an outbreak of what was described as viral gastroenteritis in his boarding school. All the other pupils have completely recovered.

A Clinical Approach

History and physical examination

The relationship of the gastrointestinal symptoms to meals needs to be determined. In true food allergy this commonly occurs soon after ingestion. Excessive bloating and diarrhoea suggests lactose intolerance. In functional gastrointestinal disorders, symptoms after meals are common but symptoms between meals are also frequent and often no food can be consistently blamed. The specific symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome should be sought (Ch 7). Individuals may react to the nutrients in food, such as protein, carbohydrate, fat, vitamins or minerals or to food additives. Foods that commonly cause reactions are summarised in Table 18.1.

Table 18.1 Main foods that commonly cause gastrointestinal disturbances

| Food type | Common examples of trigger foods |

|---|---|

| Cereal grains | Wheat |

| Dairy products | Milk, cheese |

| Fruit | Citrus Fruit |

| Vegetables | Onions, capsicum |

| Miscellaneous foods | Coffee, eggs, chocolate |

A physical examination is generally unhelpful, unless the patient is currently experiencing symptoms. Occasionally skin rashes or signs of asthma are detected. It may be helpful in excluding other disorders.

The suggested approach is to elicit three main elements from the history:

Identification of Food Allergens

Identification of contributing factors

Physical examination in the emergency department

Investigations

Morbidity and mortality associated with food allergies

The symptoms of adverse food reactions are typically manifest in the gastrointestinal tract, skin and respiratory tract. The majority of symptoms of food allergies are mild and include various gastrointestinal symptoms such as bloating, abdominal pains and nausea. However, there have been multiple reports of severe anaphylactic reactions and death following the ingestion of certain foods. Fatalities can result from severe laryngeal oedema, bronchospasm, hypotension or a combination of all of these signs.

Pharmacological management of food allergies

Non-IgE-mediated food allergies are more difficult to diagnose and manage than IgE-mediated allergies for several reasons. They are cell-mediated allergies and have a slow disease course compared to IgE-mediated reactions. The established tests of skin-prick testing and serum measurements of food-specific IgE levels are less sensitive in these allergies. This dictates that the overall management is different to IgE-mediated allergies. The most widely studied non-IgE-mediated food allergy has been eosinophilic oesophagitis. This is characterised by oesophageal intraepithelial eosinophilic infiltration (Ch 2).

Corticosteroids are the current mainstay of treatment in eosinophilic oesophagitis. Oral methylprednisolone was given for 4 weeks to 20 children with eosinophilic oesophagitis and resulted in a dramatic histological and clinical improvement in the vast majority of patients. However, systemic side effects of corticosteroids limit their use in this disease, particularly in a paediatric population. A different route of administration of corticosteroid, which involves ‘topical’ administration consisting of swallowed aerosolised fluticasone propionate, has been developed. A recent published randomised controlled trial performed over 3 months in paediatric patients with eosinophilic oesophagitis resulted in 50% histological remission in those who were treated with fluticasone, compared with 9% remission in placebo-treated patients. Troublesome side effects have been noted with this therapy. They include oesophageal candidiasis. Disease relapse was observed on their discontinuation.

Food Intolerance

Lactose intolerance

Management of lactose malabsorption generally takes the form of three approaches:

Pharmacologically related adverse food reactions

These reactions cannot be diagnosed accurately by any available skin or blood test.

The chemicals in the responsible foods are best identified by systematic diets and oral challenge:

Summary

Education is of paramount importance to patients with food allergies. Patients should be given information to contact their local food allergy organisation and the International Food Information Council. The patient should be referred to an immunologist in cases where IgE-mediated reactions are suspected. The diagnosis and management of non-IgE-mediated allergies is more complex and should involve a gastroenterologist and an immunologist. Once a food allergy has been diagnosed, it is important that the trigger allergen is strictly avoided whether by ingestion, skin contact or inhalation.

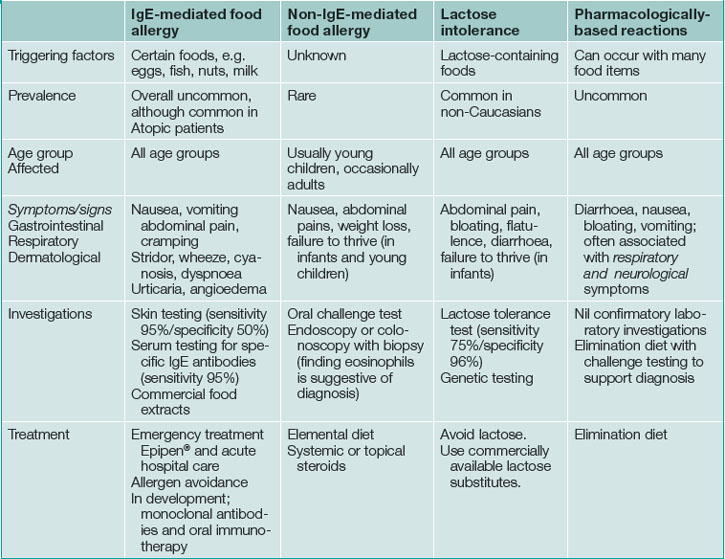

For lactose intolerance and pharmacologically related reactions, the main treatments which appear to be useful are food avoidance and an elimination diet respectively (see Table 18.2).

Key Points

Burks A.W., James J.M., Hiegel A., et al. Atopic dermatitis and food hypersensitivity reactions. J Pediatr. 1998;132(1):132-136.

Enrique E., Pineda F., Malek T., et al. Sublingual immunotherapy for hazelnut food allergy: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study with a standardized hazelnut extract. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116(5):1073-1079.

Jansen J.J., Kardinaal A.F., Huijbers G., et al. Prevalence of food allergy and intolerance in the adult Dutch population. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1994;93(2):446-456.

Kagalwalla A.F., Sentongo T.A., Ritz S., et al. Effect of six-food elimination diet on clinical and histologic outcomes in eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4(9):1097-1102.

Kelly K.J., Lazenby A.J., Rowe P.C., et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis attributed to gastroesophageal reflux: improvement with an amino acid-based formula. Gastroenterology. 1995;109(5):1503-1512.

Konikoff M.R., Noel R.J., Blanchard C., et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of fluticasone propionate for pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2006;131(5):1381-1391.

Leung D.Y., Sampson H.A., Yunginger J.W., et al. Effect of anti-IgE therapy in patients with peanut allergy. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(11):986-993.

Liacouras C.A., Spergel J.M., Ruchelli E., et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis: a 10-year experience in 381 children. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3(12):1198-1206.

Markowitz J.E., Spergel J.M., Ruchelli E., et al. Elemental diet is an effective treatment for eosinophilic esophagitis in children and adolescents. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98(4):777-782.

Patriarca G., Nucera E., Pollastrini E., et al. Oral specific desensitization in food-allergic children. Dig Dis Sci.. 2007;52(7):1662-1672.

Rasinpera H., Savilahti E., Enattah N.S., et al. A genetic test which can be used to diagnose adult-type hypolactasia in children. Gut. 2004;53(11):1571-1576.

Sampson H.A., Anderson J.A. Summary and recommendations: classification of gastrointestinal manifestations due to immunologic reactions to foods in infants and young children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2000;30(suppl):S87-S94.

Sicherer S.H., Sampson H.A. Food hypersensitivity and atopic dermatitis: pathophysiology, epidemiology, diagnosis, and management. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999;104(3 Pt 2):S114-S122.

Spergel J.M., Andrews T., Brown-Whitehorn T.F., et al. Treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis with specific food elimination diet directed by a combination of skin prick and patch tests. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2005;95(4):336-343.

Young E., Stoneham M.D., Petruckevitch A., et al. A population study of food intolerance. Lancet. 1994;343(8906):1127-1130.