CHAPTER 57 Fistulae

Aetiology and Epidemiology

The aetiology of urogenital fistulae is varied, and may be broadly categorized into congenital or acquired, the latter being divided into obstetric, surgical, radiation, malignant and miscellaneous causes. The same factors may be responsible for intestinogenital fistulae, although inflammatory bowel disease is an additional important aetiological factor here. In most developing countries, over 90% of fistulae are of obstetric aetiology, whereas in the UK, approximately 70% follow pelvic surgery (Table 57.1).

Table 57.1 Aetiology of urogenital fistulae in two series from the north-east of England (Hilton unpublished) and from south-east Nigeria (Hilton and Ward 1998)

| Aetiology | North-east England (n = 300) | South-east Nigeria (n = 2389) |

|---|---|---|

| Obstetric | ||

| Obstructed labour | 2 | 1918 |

| Caesarean section | 13 | 165 |

| Ruptured uterus | 8 | 119 |

| Forceps/ventouse | 5 | |

| Breech extraction | 1 | |

| Placental abruption | 1 | |

| Caesarean hysterectomy | 3 | |

| Symphysiotomy | 2 | |

| Obstetric subtotal (% of total) | 35 (11.7%) | 2202 (92.2%) |

| Surgical | ||

| Abdominal hysterectomy | 120 | 33 |

| Radical hysterectomy | 15 | |

| Urethral diverticulectomy | 15 | |

| Colectomy | 9 | |

| Colporrhaphy | 9 | 35 |

| Vaginal hysterectomy | 5 | 25 |

| Midurethral tape procedures | 4 | |

| Laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy | 3 | |

| Cystoplasty and colposuspension | 2 | |

| Colposuspension | 2 | |

| Cervical stumpectomy | 2 | |

| Large loop excision of the transformation zone | 2 | |

| Nephroureterectomy | 2 | |

| Subtotal hysterectomy | 2 | |

| Total abdominal hysterectomy and colporrhaphy | 1 | |

| Total abdominal hysterectomy and colposuspension | 1 | |

| Laparoscopic oophorectomy | 1 | |

| Sling | 2 | |

| Partial vaginectomy | 3 | |

| Periurethral bulking agents | 1 | |

| Needle suspension | 1 | |

| Subtrigonal phenol injection | 1 | |

| Lithocast | 1 | |

| Ileoanal pouch | 1 | |

| Sacrospinous fixation | 1 | |

| Unknown surgery in childhood | 1 | |

| Suture to vaginal laceration | 12 | |

| Surgical subtotal (% of total) | 207 (69.0%) | 105 (4.4%) |

| Radiation | ||

| Radiation subtotal (% of total) | 28 (9.3%) | 0 |

| Malignancy | ||

| Malignancy subtotal (% of total) | 2 (0.7%) | 42 (1.8%) |

| Miscellaneous | ||

| Vaginal pessary | 8 | |

| Infection | 5 | 7 |

| Congenital | 5 | |

| Foreign body | 4 | |

| Catheter induced | 3 | |

| Trauma | 2 | 11 |

| Coital injury | 1 | 22 |

| Miscellaneous subtotal (% of total) | 28 (9.3%) | 40 (1.7%) |

Sources: Hilton (unpublished).

Hilton P, Ward A 1998 Epidemiological and surgical aspects of urogenital fistulae: a review of 25 years experience in south-east Nigeria. International Urogynecology Journal and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction 9: 189–194.

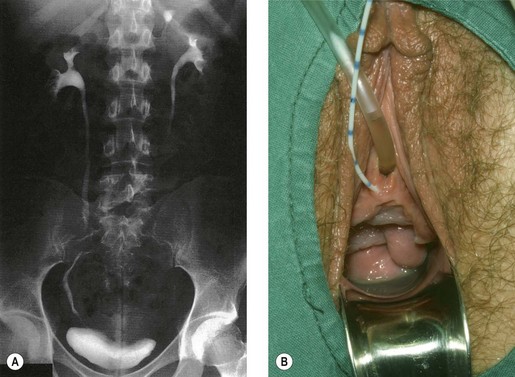

Congenital fistulae are strictly outside the scope of this chapter, and readers are advised to refer to Chapter 13 for further information. Some cases of ectopic ureter may discharge into the vagina, and their presentation may be delayed into teens or adult life, hence leading to confusion with acquired fistulae or other causes of incontinence. This occurs particularly if the abnormal ureter is only draining a small or poorly functioning part of the renal tissue. Under these circumstances, the abnormal tissue may be insufficient to show up as a soft tissue shadow on a plain X-ray, and so poorly functional that it is not easily seen on excretion urography. A high index of clinical suspicion is required if the diagnosis is not to be overlooked (Figure 57.1A,B).

Obstetric

The overwhelming majority are complications of neglected obstructed labour. During normal labour, the bladder is displaced upwards and the anterior vaginal wall, bladder base and urethra are compressed between the fetal head and the posterior surface of the pubis. No harm results if this occurs for a short time, but in prolonged obstructed labour, the intervening tissues are devitalized by ischaemia. Usually, the anterior vaginal wall and underlying bladder neck are affected, although the area of necrosis is sometimes higher, in which case the anterior lip of the cervix and underlying trigone are involved. Compression of the soft tissues between the sacral promontory and the presenting part may occur at the same time, with necrosis at the posterior vaginal wall and underlying rectum. The devitalized area separates as a slough usually between the third and 10th day of the puerperium, with resulting incontinence (Figure 57.2).

The perineum and posterior vaginal wall are, of course, at risk from even the most straightforward delivery, although primiparity, forceps delivery, birth weight over 4 kg and occipitoposterior position have been found to be significant risk factors associated with third-degree tears (Sultan et al 1994). Even when identified and repaired, this increases the risk of rectovaginal fistula.

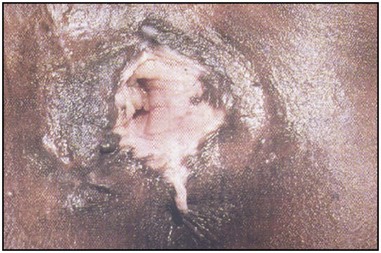

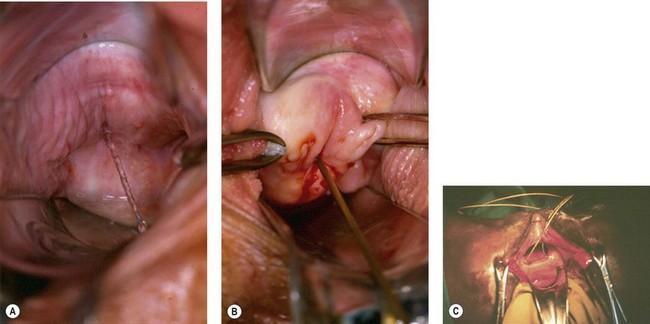

Traditional surgical practices are undertaken in up to 98% of women in some parts of Africa (United Nations Population Fund 2007, World Health Organization 2008), and may play a role in the aetiology of both direct ‘surgical’ and obstetric fistulae. The practices of ‘angurya’ and ‘gishiri’ cutting [female genital mutilation (FGM) type IV] (World Health Organization 2008) are commonly employed to treat a wide variety of conditions including obstructed labour, infertility, dyspareunia, dysuria, amenorrhoea, goitre, backache and presumed tumour. The traditional cut made with a razor blade or knife through the vaginal introitus is sometimes superficial, but may result in fistula formation (Figure 57.3). Since cuts are usually made by linear incision into healthy tissues, repair is often much easier than for those resulting from pressure necrosis. Tahzib (1983, 1985) reported on the epidemiological determinants of vesicovaginal fistulae in northern Nigeria. In 84% of cases, obstructed labour was the major aetiological factor, 33% had undergone ‘gishiri’, and this was felt to be the main aetiological factor in 15%.

Figure 57.3 Vesicovaginal fistula resulting from ‘gishiri’ cutting (female genital mutilation type IV).

Female circumcision has been practised in various forms in much of North Africa, being most prevalent in Ethiopia, Eritrea, Sudan, Egypt, Mali and Guinea, where currently over 75% of women are affected (World Health Organization 2008). The more extreme forms (previously referred to as ‘pharaonic circumcision’) involve removal of the labial minora (FGM type IIa), and may include removal of the clitoris (FGM type IIb) and labia majora (FGM type IIc) (see Figure 57.4). In FGM type III, the introitus may be reduced to pin-hole size by excision and apposition of the cut edges of the labia minora or majora (infibulation) (World Health Organization 2008). Whilst an association between FGM and both vesicovaginal and rectovaginal fistula is recognized (Lovel et al 2000), the strength of the association and the exact mechanisms are less certain and are currently under investigation (World Health Organization 2008).

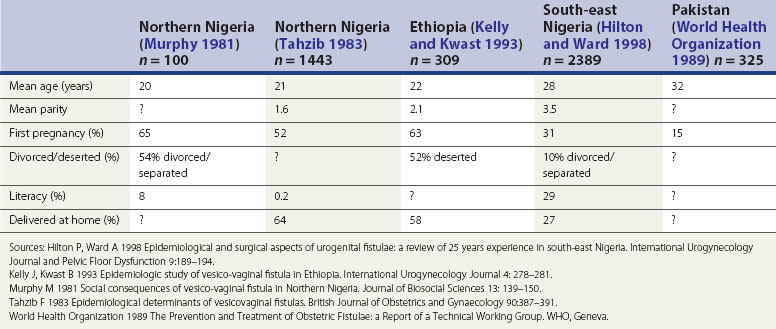

The influence of these factors is illustrated in the epidemiological studies alluded to earlier. Tahzib (1983) reported that over 50% of the cases of vesicovaginal fistulae seen in northern Nigeria were under 20 years of age, over 50% were in their first pregnancy, and only one in 500 had received any formal education. From the same area, Murphy (1981) reported that 88% of patients had married at 15 years of age or less, and 33% had delivered their first child before the age of 15 years. However, in different developing world societies, these factors do seem to have variable influence. For example, in south-east Nigeria (Hilton and Ward 1998) and the north-west frontier of Pakistan (World Health Organization 1989), fistula patients seem to be somewhat older and of higher parity; they also appear to have a higher literacy rate, and to be more likely to remain in a married relationship after the development of their fistula (Hilton and Ward 1998). It is likely that the development of fistulae here reflects other biosocial variations (Table 57.2). It is clear that in these populations, even where skilled maternity care is available, uptake may be poor. Mistrust of hospitals is commonplace, antenatal care is poorly attended, and delivery is commonly conducted at home by elderly relatives or unskilled traditional birth attendants. Where labour is prolonged, transfer to hospital may only be used as a last resort.

Surgical

Genital fistula may occur following a wide range of surgical procedures within the pelvis (Table 57.1, Figure 57.5A–F). It is often supposed that this complication results from direct injury to the lower urinary tract at the time of operation. Certainly, on occasions, this may be the case; careless, hurried or rough surgical technique makes injury to the lower urinary tract much more likely. However, of 300 fistulae referred to the author in the UK over the last 20 years, 207 have been associated with pelvic surgery and 147 followed hysterectomy; of these, only seven presented with leakage of urine on the first postoperative day. In other cases, compromise to the blood supply may result in tissue necrosis and subsequent leakage; alternatively, a small pelvic haematoma may develop in association with the vaginal vault, which subsequently becomes infected and discharges with the characteristic puff of haematuria 5–10 days later, with incontinence following shortly thereafter. Recent animal studies suggest that the inadvertent placement of vault sutures into the bladder wall at hysterectomy may not carry as great a risk of fistula formation as previously thought (Meeks et al 1997).

Although it is important to remember that the majority of surgical fistulae follow apparently straightforward hysterectomy in skilled hands, several risk factors may be identified that make direct injury more likely (Table 57.3). Obviously, anatomical distortion within the pelvis by ovarian tumour or fibroid will increase surgical difficulty, and abnormal adhesions between bladder and uterus or cervix following previous surgery or associated with previous sepsis, endometriosis or malignancy may make fistula formation more likely. Preoperative or early postoperative radiotherapy may decrease vascularity, and make the tissues generally less forgiving of poor technique.

| Risk factor | Pathology | Specific example |

|---|---|---|

| Anatomical distortion | Fibroids | |

| Ovarian mass | ||

| Abnormal tissue adhesion | Inflammation | Infection |

| Endometriosis | ||

| Previous surgery | Caesarean section | |

| Cone biopsy | ||

| Colporrhaphy | ||

| Malignancy | ||

| Impaired vascularity | Ionizing radiation | Preoperative radiotherapy |

| Metabolic abnormality | Diabetes mellitus | |

| Radical surgery | ||

| Compromised healing | Anaemia | |

| Nutritional deficiency | ||

| Abnormality of bladder function | Voiding dysfunction |

Sources: Hilton P, Ward A 1998 Epidemiological and surgical aspects of urogenital fistulae: a review of 25 years experience in south-east Nigeria. International Urogynecology Journal and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction 9: 189–194.

Kelly J, Kwast B 1993 Epidemiologic study of vesico-vaginal fistula in Ethiopia. International Urogynecology Journal 4: 278–281.

Murphy M 1981 Social consequences of vesico-vaginal fistula in Northern Nigeria. Journal of Biosocial Sciences 13: 139–150.

Tahzib F 1983 Epidemiological determinants of vesicovaginal fistulas. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 90: 387–391.

World Health Organization 1989 The Prevention and Treatment of Obstetric Fistulae: a Report of a Technical Working Group. WHO, Geneva.

It has recently been shown that there is a high incidence of abnormalities of lower urinary tract function in fistula patients (Hilton 1998); whether these abnormalities antedate the surgery, or develop with or as a consequence of the fistula, cannot be answered from this data. However, it is likely that patients with a habit of infrequent voiding, or with inefficient detrusor contractility, may be at increased risk of postoperative urinary retention; if this is not recognized early and managed appropriately, the risk of fistula formation may be increased.

Radiation

As noted above, preoperative pelvic irradiation increases the risk of postoperative fistula development, but irradiation itself may be a cause of fistula (Figure 57.5G). The obliterative endarteritis associated with ionizing radiation in therapeutic dosage proceeds over many years, and may be aetiological in fistula formation long after the primary malignancy has been treated. Of the 28 radiation fistulae in the author’s series, the fistulae developed at intervals between 1 and 30 years following radiotherapy. Not only does this ischaemia produce the fistulae, it also causes significant damage in the adjacent tissues, so ordinary surgical repair has a high likelihood of failure and modified surgical techniques are required.

Inflammatory bowel disease

Ulcerative colitis has a small incidence of low rectovaginal fistulae. Diverticular disease can produce colovaginal fistulae and, rarely, colouterine fistulae, with surprisingly few symptoms attributable to the intestinal pathology. The possibility should not be overlooked if an elderly woman complains of feculent discharge or becomes incontinent without concomitant urinary problems (Figure 57.6).

Prevalence

United Kingdom

The prevalence of genital fistulae obviously varies from country to country and continent to continent as the main causative factors vary. Accurate figures are impossible to obtain since those areas with the highest overall prevalence are also those with the poorest systems of health data collection. UK National Health Service data reported approximately 150 operations for vesicovaginal and urethrovaginal fistula per year in England and Wales in the early 1990s (Hilton 1997). The most recent data from Health Episode Statistics for England suggest an average of 95 operations for vesicovaginal fistula and 10 operations for urethrovaginal fistula per year in England (Department of Health 2009). It is tempting to suggest that this apparent reduction in incidence of fistulae may reflect changes in the practice of hysterectomy. However, assuming that 50% of urogenital fistulae in the UK follow hysterectomy (as in the author’s series), the rate of fistula formation following hysterectomy seems, if anything, to be increasing; from approximately one in 1200 hysterectomies in the period 1990–1991 to 1994–1995 to approximately one in 750 in 2003–2004 to 2007–2008 (Department of Health 2009). Whilst there are other possible explanations, it may be that as fewer hysterectomies are undertaken, those that remain are the more difficult procedures. Studies from Finland suggest a similar rate of posthysterectomy fistulae overall, with approximately one per 1000 abdominal hysterectomies and one per 450 laparoscopic hysterectomies (Harkki-Siren et al 1998). Similarly, ureteric injury may be up to six times as common following laparoscopic hysterectomy compared with open hysterectomy (Harkki-Siren et al 1998), and two to 10 times as common following radical hysterectomy and exenteration (Averette et al 1993, Bladou et al 1995, Emmert and Köhler 1996). Sultan et al (1994) reported that third-degree tears followed 0.6% of vaginal deliveries, and a rectovaginal fistula resulted in 6% of these (one in 3000 deliveries overall).

Developing world

In the developing world, many fistula cases are unknown to medical services, being separated from their husbands and ostracized from society. Although the true prevalence in the developing world is unknown, particularly high prevalence rates are reported in Nigeria, Ethiopia, Sudan and Chad. The estimated prevalence in the developing world is one to two per 1000 deliveries, with perhaps 50,000–100,000 new cases each year. Although several units exist in Nigeria, Ethiopia and Sudan, which deal with 100–700 cases per year, this does not come close to meeting the demand, and there are estimated to be perhaps 500,000 to 2 million untreated cases worldwide (Waaldijk and Armiya’u 1993).

Classification

Many different fistula classifications have been described in the literature on the basis of anatomical site or position in relation to meatus or sphincter mechanism; these are often subclassified into simple cases (where the tissues are healthy and access is good) (Figure 57.7A,B) or complicated cases (where there is tissue loss, scarring, impaired access, involvement of the ureteric orifices, or the presence of coexistent rectovaginal fistula) (Figure 57.7C) (Lawson 1978, Waaldijk 1995, Goh 2004). Urogenital fistulae may be classified into urethral, bladder neck, subsymphysial (a complex form involving circumferential loss of the urethra with fixity to bone), midvaginal, juxtacervical or vault fistulae; massive fistulae extending from bladder neck to vault; and vesicouterine or vesicocervical fistulae. It is interesting to note that whereas over 60% of fistulae in the developing world are midvaginal, juxtacervical or massive (reflecting their obstetric aetiology) (Hilton and Ward 1998), such cases are relatively rare in Western fistula practice; in contrast, 50% of the fistulae managed in the UK are situated in the vaginal vault (reflecting their surgical aetiology). There have been recent calls for classification systems more predictive of outcome (Arrowsmith 2007, Goh et al 2008).

Presentation

Occasionally, a patient with an obvious fistula may deny incontinence, and this is presumed to reflect the ability of the levator ani muscles to occlude the vagina below the level of the fistula. Some patients with vesicocervical or vesicouterine fistula following caesarean section may maintain continence at the level of the uterine isthmus, and complain of cyclical haematuria at the time of menstruation, or menouria (Falk and Tancer 1956, Youssef 1957). In other cases, patients may complain of little more than a watery vaginal discharge, or intermittent leakage, which seems posturally related. Leakage may appear to occur specifically on standing or on lying supine, prone, or in left or right lateral positions, presumably reflecting the degree of bladder distension and the position of the fistula within the bladder; such a pattern is most unlikely to be found with ureteric fistulae.

Although in the case of direct surgical injury, leakage may occur from the first postoperative day, in most surgical and obstetric fistulae, symptoms develop between 5 and 14 days after the causative injury; however, the time of presentation may be quite variable. This will depend, to some extent, on the severity of symptoms, but as far as obstetric fistulae in the developing world are concerned, is determined more by access to health care. In a review of cases from Nigeria, the average time for presentation was over 5 years, and in some cases over 35 years, after the causative pregnancy (Hilton and Ward 1998).

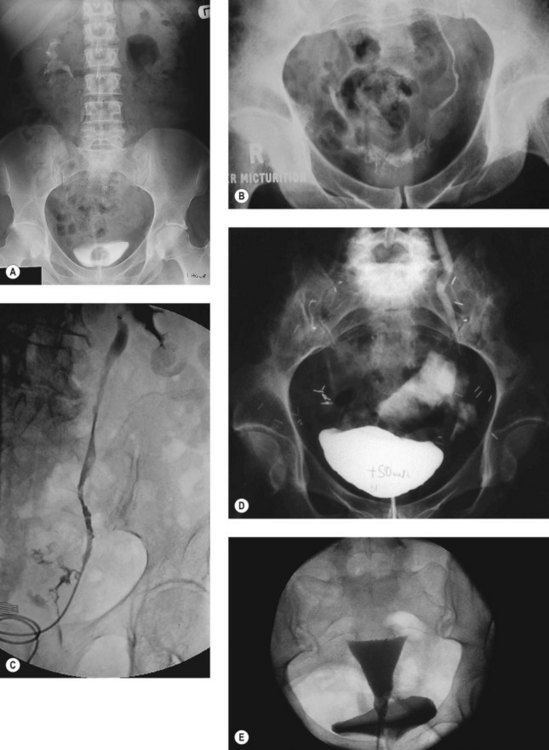

Ureteric fistulae occur from similar aetiologies to bladder fistulae, and the causative mechanism may be one of direct injury by incision, division or excision, or of ischaemia from strangulation by suture, crushing by clamp or stripping by dissection (Yeates 1987). The presentation may therefore be similarly variable. With direct injury, leakage is usually apparent from the first postoperative day. Urine output may be physiologically reduced for some hours following surgery, and if there is significant operative or postoperative hypotension, oliguria may persist longer. However, once renal function is restored, leakage will usually be apparent promptly. With other mechanisms, obstruction is likely to be present to a greater or lesser degree, and the initial symptoms may be of pyrexia or loin pain, with incontinence only occurring after sloughing of the ischaemic tissue, from around 5 days up to 6 weeks later. On occasion, the reverse pattern may be seen, with apparent relief of leakage resulting from the development of obstruction as scarring in the ureter proceeds (Figure 57.8A).

Investigations

Dye studies

Excessive vaginal discharge, or the drainage of serum from a pelvic haematoma following surgery, may simulate a urinary fistula. If the fluid is in sufficient quantity to be collected, biochemical analysis of its urea content in comparison to that of urine and serum will confirm its origin. Phenazopyridine is no longer available in the UK, although it has previously been used orally (200 mg tds) to stain the urine and hence confirm the presence of a fistula; alternatively, indigo carmine may be used intravenously for the same purpose. The identification of the site of a fistula is best carried out by the instillation of coloured dye (methylene blue or indigo carmine) into the bladder via catheter with the patient in the lithotomy position. The traditional ‘three swab test’ has its limitations and is not recommended; the examination is best carried out with direct inspection, and multiple fistulae may be located in this way. It is important to be alert for leakage around the catheter, which may spill back into the vagina creating the impression of a fistula. It is also important to ensure that adequate distension of the bladder occurs, as some fistulae do not leak at small volumes; conversely, some fistulae with an oblique track through the bladder wall may leak at small volumes but not at capacity. If leakage of clear fluid continues after dye instillation, a ureteric fistula is likely; previously, this could be confirmed by a ‘two dye test’, using phenazopyridine to stain the renal urine, and methylene blue to stain the bladder contents (Raghavaiah 1974). However, intravesical followed by intravenous injection of dye may be required nowadays.

Imaging

Excretion urography

Although intravenous urography is a particularly insensitive investigation in the diagnosis of vesicovaginal fistula, knowledge of upper urinary tract status may have a significant influence on treatment measures applied, and intravenous urography or computed tomography urogram should be looked on as an essential investigation for any suspected or confirmed urinary fistula (Figure 57.8A,B). Compromise to ureteric function is a particularly common finding when a fistula occurs in relation to malignant disease or its treatment (by radiation or surgery).

Dilatation of the ureter is characteristic in ureteric fistula, and its finding in association with a known vesicovaginal fistula should raise suspicion of a complex ureterovesicovaginal lesion. Whilst essential for the diagnosis of ureteric fistula, urography is not completely sensitive, although the presence of a periureteric flare is highly suggestive of extravasation at this site (Figure 57.8B).

Retrograde pyelography

Retrograde pyelography is a more reliable way of identifying the exact site of a ureterovaginal fistula, and may be undertaken simultaneously with either retrograde or percutaneous catheterization for therapeutic stenting of the ureter (see below) (Figure 57.8C).

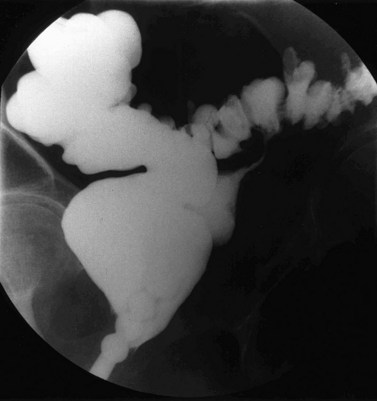

Cystography

Cystography is not particularly helpful in the basic diagnosis of vesicovaginal fistulae, and a dye test carried out under direct vision is likely to be more sensitive. It may, however, be useful in achieving a diagnosis in complex fistulae (Figure 57.8D), or vesicouterine fistulae, where a lateral view may show the cavity of the uterus filled with radiopaque dye behind the bladder.

Colpography and hysterosalpingography

If a fistula opening cannot be identified directly, colpography or hysterography may occasionally be helpful. If a large Foley catheter with a large balloon is distended in the lower vagina, injection of a non-viscous opaque medium under pressure may outline a fistulous track to an adjacent organ. However, failure to demonstrate a fistula by this means does not exclude its presence. If a patient with a vesicouterine fistula has no history of incontinence but complains of cyclical haematuria, contrast studies carried out through the uterus (hysterosalpingography) may be more rewarding than cystography. Again, a lateral view is necessary to detect the anterior leak (Figure 57.8E).

Examination under anaesthesia

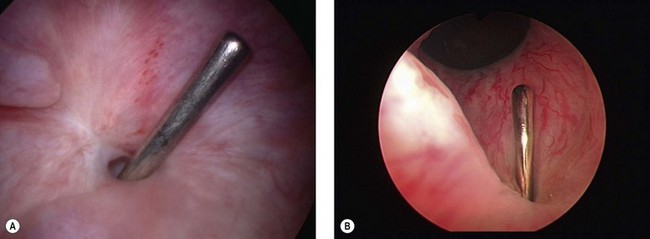

Careful examination, if necessary under anaesthetic, may be required to determine the presence of a fistula, and is deemed by several authorities to be an essential preliminary to definitive surgical treatment (Chassar Moir 1967, Lawson 1978, Jonas and Petri 1984, Lawson and Hudson 1987). A malleable silver probe is invaluable for exploration of the vaginal walls, and tissue forceps or plastic surgical skin hooks are helpful to put tension on the tissues for the identification of small fistulae. If the probe passes directly into the rectum, it may be felt digitally or seen via the proctoscope. In the bladder or urethra, it may be identified by a metallic click against a silver catheter, or seen by a cystoscope; in either case, the diagnosis is then obvious.

It is also important at the time of examination to assess the available access for repair vaginally, and the mobility of the tissues (Figure 57.7A,B). The decision between the vaginal and abdominal approaches to surgery is thus made; when the vaginal route is chosen, it may be appropriate to select between the more conventional supine lithotomy with a head-down tilt, and the prone (reverse lithotomy) with head-up tilt (Figure 57.9). This may be particularly useful in allowing the operator to look down on to bladder neck and subsymphysial fistulae, and is also of advantage in some massive fistulae in encouraging the reduction of the prolapsed bladder mucosa (Lawson 1967).

Endoscopy

Cystoscopy

Although some authorities suggest that endoscopy has little role in the evaluation of fistulae, it is the author’s practice to perform cystourethroscopy in all but the largest defects (Figure 57.10). Although in some obstetric and radiation fistulae, the size of the defect and the extent of tissue loss and scarring may make it difficult to distend the bladder, much useful information is still obtained. The exact level and position of the fistula should be determined, and its relationship to the ureteric orifices and bladder neck are particularly important. With urethral and bladder neck fistulae, the failure to pass a cystoscope or sound may indicate that there has been circumferential loss of the proximal urethra; a circumstance which is of considerable importance in determining the appropriate surgical technique and the likelihood of subsequent urethral incompetence. Similar considerations may apply to investigation of the lower bowel following major obstetric injuries in which segmental circumferential loss of the upper rectum may have occurred.

The condition of the tissues must be assessed carefully. Persistence of slough means that surgery should be deferred, and this is particularly important in obstetric and postradiation cases. Biopsy from the edge of a fistula should be taken in radiation fistulae, if persistent or recurrent malignancy is suspected. Malignant change has been reported in a longstanding benign fistula, so where there is any doubt at all about the nature of the tissues, biopsy should be undertaken (Hudson 1968). In areas of endemicity, evidence of schistosomiasis, tuberculosis and lymphogranuloma may become apparent in biopsy material, and again it is important that specific antimicrobial treatment is instituted prior to definitive surgery. If calculi are identified clinically, radiologically or endoscopically in the bladder, vaginal vault or diverticulum, their removal prior to any attempt at surgical correction is essential.

Management

Immediate management

Before epithelialization is complete, an abnormal communication between viscera will tend to close spontaneously, provided that the natural outflow is unobstructed. Normal continence mechanisms, however, involve the intermittent physiological contraction of urethral and anal sphincters (see Chapter 50). As a result, although spontaneous closure of genital tract fistulae does occur, it is the exception rather than the rule. Bypassing the sphincter mechanisms, or diverting flow around the fistula (e.g. by urinary catheterization or defunctioning colostomy), may encourage closure.

The early management is of critical importance, and depends on the aetiology and site of the lesion. If surgical trauma is recognized within the first 24 h post operatively, immediate repair may be appropriate, provided that extravasation of urine into the tissues has not been great. The majority of surgical fistulae are, however, recognized between 5 and 21 days post operatively, and these should be treated with continuous bladder drainage. It is worth persisting with this line of management in vesicovaginal or urethrovaginal fistulae for 6–8 weeks since spontaneous closure may occur within this period (Davits and Miranda 1991). Although only 8% of the fistulae in the author’s series are known to have healed with catheter drainage, it is possible that the actual rate of spontaneous healing in surgical fistulae is as high as 20%.

Obstetric fistulae developing after obstructed labour should also be treated by continuous bladder drainage (Waaldijk 1994a), combined with antibiotics to limit tissue damage from infection. Indeed, if a patient is known to have been in obstructed labour for any significant length of time, or is recognized to have areas of slough on the vaginal walls in the puerperium, or has any indication of urine leakage, prophylactic catheterization should be undertaken; with this approach, spontaneous healing has been reported in up to 28% of cases (Waaldijk 1997). If sloughing of the rectal wall has also occurred, faecal discharge will adversely affect spontaneous healing, and temporary defunctioning colostomy should be performed.

The management of ureterovaginal fistulae is beyond the skill of most gynaecologists, and even those with specialist skills in urogynaecology are likely to liaise with urological and radiological colleagues in this situation. Whilst in the past, ureteric reimplantation has been looked on as the preferred approach in most cases, the use of stents inserted either in retrograde (endoscopically) or antegrade (percutaneously) fashion is successful in the majority of cases unless there is complete obstruction (Chang et al 1987, Schwartz and Stoller 2000). Where stenting cannot be achieved, or does not result in closure of the fistula, definitive surgery should be undertaken at 4–6 weeks, unless progressive calyceal dilatation or impairment of function demands earlier intervention.

The immediate management of obstetric third-degree tears has traditionally been thought to lead to good outcome. Recent data suggest that approximately half of patients sustaining such injuries will have subsequent defaecatory symptoms as a result of sphincter disruption rather than denervation, and 6% may end up with rectovaginal fistulae (Sultan et al 1994). It has not been investigated whether primary repair by a more experienced surgeon or delayed repair would improve outcome.

Palliation and skin care

The vulval skin may be at considerable risk from ammoniacal dermatitis, and liberal use of silicone barrier cream should be encouraged. Steroid therapy has been advocated in the past as a means of reducing tissue oedema and fibrosis, although these benefits are refuted and there may be a risk of compromise to subsequent healing (Jonas and Petri 1984). Local oestrogen has been recommended by some authors (Kelly 1983, Jonas and Petri 1984), and whilst empirically, one might expect benefit in postmenopausal women or those obstetric fistula patients with prolonged amenorrhoea, the evidence for this is lacking.

Physiotherapy

Obstetric fistulae are commonly associated with lower limb weakness, foot drop and limb contracture. In a group of 479 patients studied prospectively, 27% had signs of peroneal nerve weakness at presentation, and a further 38%, whilst having no current signs, gave a history of relevant symptoms (Waaldijk and Elkins 1994). Early involvement of the physiotherapist in preoperative management and rehabilitation of such patients is essential.

Antimicrobial therapy

In tropical countries, the treatment of malaria, typhoid, tuberculosis and parasitic infections should be rigorously undertaken before elective surgery. There is no evidence of benefit from prophylactic antibiotics in the management of obstetric fistulae (Tomlinson and Thornton 1998). Opinions differ on the desirability of prophylactic antibiotic cover for surgery in the developed world, with some avoiding their use other than in the treatment of specific infection, and some advocating broad-spectrum treatment in all cases. The author’s current practice is for single-dose prophylaxis with co-amoxiclav in urinary fistulae, and 5 days cover for intestinal fistulae using metronidazole and cefuroxime. Only symptomatic urinary tract infections need to be treated in the catheterized patient.

Counselling

Surgical fistula patients are usually previously healthy individuals who entered hospital for what was expected to be a routine procedure, and they end up with symptoms infinitely worse than their initial complaint. Obstetric fistula patients in the developing world are social outcasts. In both situations, therefore, these women are invariably devastated by their situation; significant impact on their mental health has been objectively confirmed (Browning et al 2007). It is vital that they understand the nature of the problem, why it has arisen, and the plan for management at all stages. Confident but realistic counselling by the surgeon is essential, and the involvement of nursing staff or counsellors with experience of fistula patients is also highly desirable. The support given by previously treated sufferers can also be of immense value in maintaining patient morale, especially where a delay prior to definitive treatment is required.

General principles of surgical treatment

Details of individual operations are outside the scope of this chapter, and readers wishing for further information about this aspect of fistula management are referred to operative surgical texts or more specific texts on the subject (Chassar Moir 1967, Lawson and Hudson 1987, Zacharin 1988, Mundy 1993, Waaldijk 1994b).

Timing of repair

The timing of surgical repair is perhaps the single most contentious aspect of fistula management. Whilst shortening the waiting period is of both social and psychological benefit to what are always very distressed patients, one must not trade these issues for compromise to surgical success. The benefit of delay is to allow slough to separate and inflammatory change to resolve. In both obstetric and radiation fistulae, there is considerable sloughing of tissues, and it is imperative that this should have settled before repair is undertaken. In radiation fistulae, it may be necessary to wait 12 months or more. In obstetric cases, most authorities suggest that a minimum of 3 months should be allowed to elapse, although Waaldijk (1994a) has advocated surgery as soon as slough is separated.

With surgical fistulae, the same principles should apply, and although the extent of sloughing is limited, extravasation of urine into the pelvic tissues inevitably sets up some inflammatory response. Although early repair is advocated by several authors (Iselin et al 1998), most would agree that 10–12 weeks after surgery is the earliest appropriate time for repair.

Route of repair

Many urologists advocate an abdominal approach for all fistula repairs, claiming the possibility of earlier intervention and higher success rates in justification. Others suggest that all fistulae can be successfully closed by the vaginal route (Waaldijk 1994b). Such arguments have little merit, and both approaches have their place. Surgeons involved in fistula management must be capable of both approaches, and have the versatility to modify their techniques to select that most appropriate to the individual case. Where access is good and the vaginal tissues are sufficiently mobile, the vaginal route is usually most appropriate. If access is poor and the fistula cannot be brought within reach, the abdominal approach should be used. Although such difficulties can sometimes be handled vaginally, an abdominal procedure may be used to advantage where there is concurrent involvement of ureter or bowel in a surgical fistula.

Overall, more surgical fistulae are likely to require an abdominal repair than obstetric fistulae, although in the author’s series of cases from the UK, and those reviewed from Nigeria, two-thirds of cases were satisfactorily treated by the vaginal route, regardless of aetiology (Table 57.4).

Table 57.4 Route of primary repair (i.e. first repair at referral centre) of urogenital fistulae in two series from the north-east of England (Hilton unpublished) and from south-east Nigeria (Hilton and Ward 1998)

| Route of repair (primary procedure) | North-east England (n = 249) % | South-east Nigeria (n = 2485) % |

|---|---|---|

| Abdominal | 34.8 | 17.0 |

| Transperitoneal | 18.6 | 13.4 |

| Transvesical | 6.5 | |

| Ureteric reimplantation/stenting | 7.7 | 3.0 |

| Ureterosigmoid transplantation | 0 | 0.6 |

| Ileal conduit | 2.0 | 0 |

| Vaginal | 64.4 | 80.0 |

| Layer dissection | 40.5 | 80.0 |

| Layer dissection + Martius graft | 11.7 | 0 |

| Urethral reconstruction | 6.5 | |

| Colpocleisis | 5.3 | 0 |

| Urethrocleisis + insertion of suprapubic catheter | 0.4 | |

| Vaginal, reverse lithotomy | 0.8 | 3.0 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 |

Sources: Hilton (unpublished).

Hilton P, Ward A 1998 Epidemiological and surgical aspects of urogenital fistulae: a review of 25 years experience in south-east Nigeria. International Urogynecology Journal and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction 9: 189–194.

Instruments

All operators have their own favoured instruments, although those described in the treatise by Chassar Moir (1967) and Lawson (1967) are eminently suitable for repair by any route (Figure 57.11).

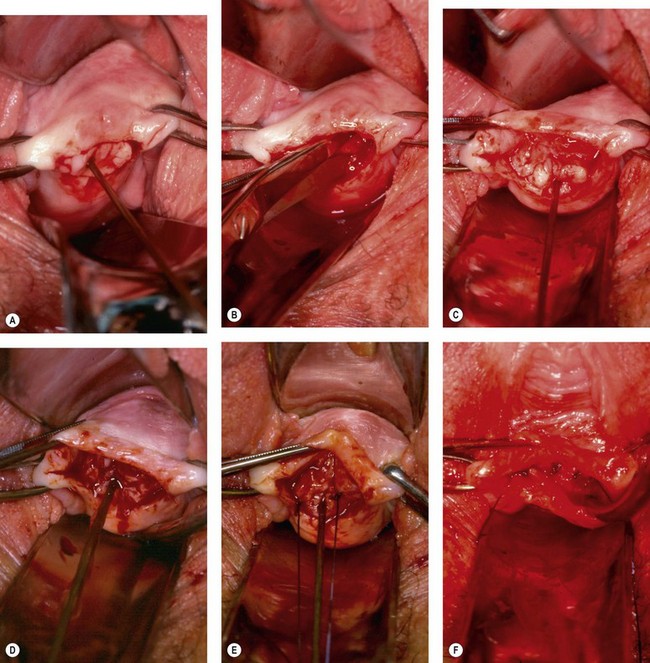

Dissection

Great care must be taken over the initial dissection of the fistula, and one should probably take as long over this as over the repair itself. Preliminary infiltration with 1 : 200,000 solution of adrenaline may help to separate planes and reduce oozing. The fistula should be circumcised in the most convenient orientation, depending on size and access. All things being equal, a longitudinal incision should be made around urethral or midvaginal fistulae, so that during repair, sutures tend to close the bladder neck; conversely, vault fistulae are better handled by a transverse elliptical incision, so that sutures do not tend to approximate the ureters during repair (Figure 57.12A).

The tissue planes are often obliterated by scarring, and dissection close to a fistula should therefore be undertaken with a scalpel or scissors (Figure 57.12B). Sharp dissection is easier with counter traction applied by skin hooks, tissue forceps or retraction sutures. Blunt dissection with small pledgets may be helpful once the planes are established, and provided one is away from the fistula edge. Wide mobilization should be performed, so that tension on the repair is minimized (Figure 57.12C).

There are arguments over the benefits of excision of the fistula track itself. Excision of the bladder walls is probably unwise, as it enlarges the defect and may increase the amount of bleeding into the bladder. However, limited excision of the scarred vaginal wall is usually appropriate (Figure 57.12D).

Specific repair techniques

Vaginal procedures

Dissection and repair in layers

There are two main types of closure technique applied to the repair of urinary fistulae: the classical saucerization technique described by Sims (1852), and the much more commonly used dissection and repair in layers. Sutures must be placed with meticulous accuracy in the bladder wall, with care being taken not to penetrate the mucosa, which should be inverted as far as possible. The repair should be started at either end, working towards the midline, so that the least accessible aspects are sutured first (Figure 57.12E). Interrupted sutures are preferred and should be placed approximately 3 mm apart, taking as large a bite of tissue as feasible. Stitches that are too close together, or the use of continuous or purse-string sutures, tend to impair blood supply and interfere with healing. Knots must be secure with three hitches, so that they can be cut short leaving the minimum amount of material within the body of the repair.

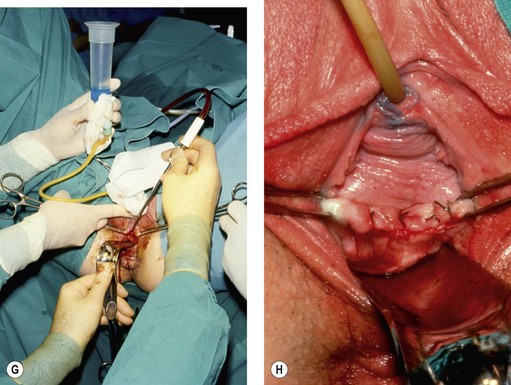

With dissection and repair in layers, the first layer of sutures in the bladder should invert the edges (Figure 57.12E); the second adds bulk to the repair by taking a wide bite of bladder wall, but also closes off dead space by catching the back of the vaginal flaps (Figure 57.12F). After testing the repair (Figure 57.12G) (see below), a third layer of interrupted mattress sutures is used to evert and close the vaginal wall, consolidating the repair by picking up the underlying bladder wall (Figure 57.12H).

Vaginal repair procedures in specific circumstances

Vault fistulae, particularly those following hysterectomy, can usually be managed vaginally. The vault is incised transversely, and mobilization of the fistula is often aided by deliberate opening of the pouch of Douglas (Lawson 1972). The peritoneal opening does not need to be closed separately, but is incorporated into the vaginal closure.

Where there is substantial urethral loss, reconstruction may be undertaken using the method described by Chassar Moir (1967) or Hamlin and Nicholson (1969). A strip of anterior vaginal wall is constructed into a tube over a catheter. Plication behind the bladder neck is probably important if continence is to be achieved. The interposition of a labial fat or muscle graft not only fills up the potential dead space, but also provides additional bladder neck support and improves continence by reducing scarring between bladder neck and vagina.

With very large fistulae extending from bladder neck to vault, the extensive dissection required may produce considerable bleeding. The main surgical difficulty is to avoid the ureters. They are usually situated close to the superolateral angles of the fistula, and if they can be identified, they should be catheterized (Figure 57.8). Straight ureteric catheters passed transurethrally or double pigtail catheters may be useful in directing the intramural portion of the ureters internally; nevertheless, great care must be taken during dissection.

Interposition grafting

Several techniques have been described to support fistula repair in different sites, although the precise role of such grafts is unclear. Some claim that the interposed tissue may serve to create an additional layer in the repair, to fill dead space and to bring in new blood supply to the area, and hence may be of particular value where there is sphincter involvement, and in multiple or recurrent fistulae (Rangnekar et al 2000) or following radiotherapy (Kiricuta 1965). Others, however, have questioned their value (Browning 2006a). There are no randomized data establishing the role of interposition grafts. In retrospective, uncontrolled or non-randomized cohort studies, it is perhaps inevitable that surgeons will have employed grafting in their more complex cases, resulting in misleading conclusions regarding the value of the procedure. The tissues used include the following.

Postoperative management

Bladder drainage

Continuous bladder drainage in the postoperative period is crucial to success, and where failure occurs after a straightforward repair, it is almost always possible to identify a period during which free drainage was interrupted. Nursing staff should check catheters hourly throughout each day, to confirm free drainage and check output. Catheters should, of course, drain into a sterile closed drainage system with a non-return valve (Hilton 1987). In circumstances where supplies of sterile disposables are limited or where standards of nursing are poor, as in many developing countries, open drainage has been advocated with good success and low infection rates. Bladder irrigation and suction drainage are no longer recommended.

Views differ regarding the ideal type of catheter. The calibre must be sufficient to prevent blockage, although whether the suprapubic or urethral route is used is, to a large extent, a matter of individual preference. A urethral Foley catheter should probably be avoided following bladder neck fistulae, and either a suprapubic catheter or a non-balloon urethral catheter sutured in place would be preferred. The bladder should not be distended to insert a suprapubic catheter after a vaginal repair, although it could be inserted before surgery by the technique of cutting on to a sound. The author’s usual practice is to use a ‘belt and braces approach’ of both urethral and suprapubic drainage initially, so that if one becomes blocked, free drainage is still maintained. The urethral catheter is removed first, and the suprapubic catheter retained and used to assess residual volume until the patient is voiding normally (Hilton 1987).

The duration of free drainage depends on the fistula type. Following repair of surgical fistulae, 12 days is adequate. With obstetric fistulae, up to 21 days of drainage may be appropriate, although recent data suggest that this may not be necessary for less complicated cases (Nardos et al 2008). Following repair of radiation fistulae, 21–42 days of drainage may be appropriate. In any of these situations, it is wise to carry out dye testing (see above) prior to catheter removal if there is any doubt about the integrity of the repair. Where a persistent leak is identified, free drainage should be maintained for 6 weeks.

Prognosis

Results

It is difficult to compare the results of treatment in different series since the lesions involved and the techniques of repair vary so greatly. Cure rates should be considered in terms of closure at first operation, and vary from 60% to 98% (Turner-Warwick et al 1967, Hamlin and Nicholson 1969, Chassar Moir 1973, Hudson et al 1975, Goodwin and Scardino 1979, Patil et al 1980, O’Conor 1980, Wein et al 1980, Elkins et al 1988, Lee et al 1988, World Health Organization 1989, Hilton 1995, Hilton and Ward 1998). In ideal circumstances, one might anticipate an 80% continence rate, 10% failures and, in the case of obstetric fistulae at least, 10% suffering from postfistula stress incontinence.

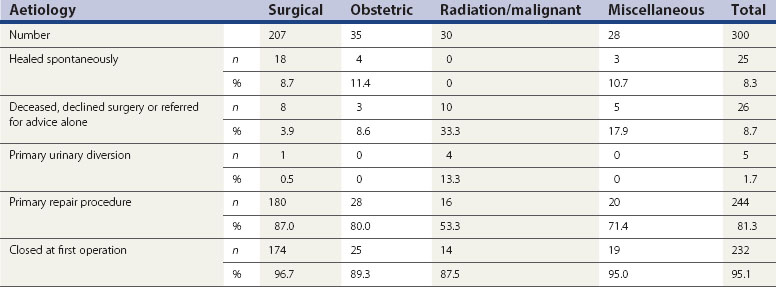

Of the 300 patients in the author’s series managed in the UK, 25 (8.3%) healed without operation, 10 (3.3%) declined surgery, 12 (4.0%) were telephone referrals only and either healed spontaneously or were treated at their local hospital, five (1.7%) underwent primary urinary diversion, and four died from malignancy or the effects of radiation prior to treatment. Of the remaining 244 who have undergone repair surgery, 232 (95.1%) were closed at their first operation, although of these, 12 (5.2%) have some residual incontinence. More specifically, the rate of closure at first operation in the author’s series is 97% in surgical cases, 95% in miscellaneous cases, 89% in obstetric cases and 88% in radiotherapy cases. Of the 130 fistulae following simple hysterectomy undergoing surgical treatment in Newcastle, 128 (98.5%) were cured at their first operation (Table 57.5).

Table 57.5 Outcome of treatment in the author’s series of urogenital fistulae treated in the north-east of England between 1987 and 2008

Long-term outcome has rarely been considered. Dolan et al (2008) reported a median 4 year follow-up of women undergoing fistula repair in the UK. Despite their fistulae being anatomically closed, most women reported one or more urinary symptoms in the long term, although only one in eight found these symptoms significantly problematic. Frequency, nocturia, and stress or urge incontinence were the most common troublesome symptoms, and there was no obvious trend to improvement over time.

Of the largely obstetric fistulae reviewed from Nigeria by Hilton and Ward (1998), 81.2% were cured by the first operation and 97.7% were eventually successfully anatomically repaired, with only 0.6% undergoing urinary diversion. It is commonly assumed that follow-up of obstetric fistula patients after discharge from hospital is not feasible; however, two recent studies have found this not to be the case (Browning and Menber 2008, Nielsen et al 2009). Both studies found fistula closure to be associated with improvement in quality of life and reintegration into society. In the longer-term follow-up study of Browning and Menber (2008), although incontinence persisted in some patients, there was a tendency to further improvement over time.

A law of diminishing returns has been reported previously (Lawson 1978). Although repeat operations are certainly justified, the success rate decreases progressively with increasing numbers of previous unsuccessful procedures. In the series reported from Nigeria, although the cure rate at first operation was 81.7%, the success rate for those patients requiring two or more procedures fell to 65% (Hilton and Ward 1998). It cannot be overemphasized that the best prospect for cure is at the first operation, and there is no place for the well-intentioned occasional fistula surgeon, be they gynaecologist or urologist.

Postfistula stress incontinence

Stress incontinence has long been recognized as a complication of vesicovaginal fistulae (Lawson 1967). It is most likely to occur in obstetric fistula patients when the injury involves the sphincter mechanism, particularly if there is tissue loss (Waaldijk 1989, Browning 2006b), although it has also been reported in a large proportion of surgical fistulae involving the urethra or bladder neck (Hilton 1998). It affects at least 10% of all fistula patients, and its impact in terms of the patient’s quality of life and mental health may be as great as that of the fistula itself (Browning et al 2007).

The extent of scarring in the area means that conventional approaches to bladder neck elevation may be technically difficult and of limited success. The use of a labial musculofat graft in the initial repair may reduce the likelihood of the complication (Waaldijk 1994b), and a number of other techniques have been attempted (Hudson et al 1975, Waaldijk 1994b). The implantation of an artificial urinary sphincter or neourethral reconstruction may be appropriate from a theoretical point of view (Hilton 1990), but the former would be prohibitively expensive, and both would be excessively morbid, for use in the developing world. Periurethral injections hold promise as a minimally invasive technique particularly appropriate in the situation of urethral insufficiency with a relatively fixed immobile urethra. Although initial success has been reported in postfistula stress incontinent patients (Hilton et al 1998), the long-term outcomes are disappointing.

Subsequent pregnancy

Although many patients with obstetric vesicovaginal fistula will experience amenorrhoea for 2 years or more after the causative pregnancy (Hilton and Ward 1998), where tissue loss is not great, hypothalamic function often returns to normal immediately after successful repair, and fertility may be relatively normal. Kelly (1979) reported on 33 patients who became pregnant within 1 year of fistula repair, 12 of whom were delivered vaginally without damage to the repair. His criteria for attempting vaginal delivery were: that the fistula arose from a non-recurring cause (i.e. malpresentation as opposed to pelvic contraction), that an interposition graft had been utilized in the repair, and that the labour was conducted under skilled supervision in hospital (Kelly 1979). However, most other authorities have emphasized the need for caesarean section in any subsequent pregnancy (Lawson 1978). Most recently, in a study from Ethiopia, Browning (2009) described no recurrent fistulae, and 47 livebirths from 49 pregnancies delivered by a policy of elective caesarean section (in the rare cases where dates were certain) or emergency caesarean section at premature rupture of membranes or onset of labour.

Prevention

It has been estimated by the World Health Organization (WHO) that there are approximately 500,000 maternal deaths per year worldwide (World Health Organization 1989), and it is clear that the prevalence of obstetric fistulae and maternal mortality rates are closely related. Indeed, one might look on the vesicovaginal fistula patient as being the ‘near-miss’ maternal death. In recognition of this fact, WHO established, through their ‘Safe Motherhood Initiative’, a technical working group to investigate the problems of prevention and management of obstetric fistulae. The recommendations from that working group included the extension of antenatal and intrapartum care; the transfer of women in prolonged labour for delivery by skilled personnel; the identification of areas where fistulae are still prevalent, so that resources could be mobilized to deal with fistulae more effectively; and the creation of specialized centres for management, training and research, with a specific aim of treating existing cases within 5 years (World Health Organization 1989). One thousand years ago, Avicenna recognized the problems of early childbearing, saying: ‘in cases where women are married too young the physician should instruct the patient in the ways of prevent of pregnancy. In these patients the bulk of the fetus may cause a tear in the bladder which results in incontinence of urine which is incurable and remains until death’ (Hilton 1995). Clearly, the achievement of WHO’s aims and recommendations is critically dependent on major social change in areas of endemicity. Without improvement in the status of women, an extension of primary education, deferment of marriage and childbearing, improved nutritional status and contraceptive services, and skilled attendants in childbirth throughout the world, the problem of obstetric fistulae will remain with us well into the new millennium.

KEY POINTS

Arrowsmith S. The classification of obstetric vesico-vaginal fistulas: a call for an evidence-based approach. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 2007;99(Suppl 1):S25-S27.

Averette HE, Nguyen HN, Donato DM, et al. Radical hysterectomy for invasive cervical cancer. A 25-year prospective experience with the Miami technique. Cancer. 1993;71:1422-1437.

Bladou F, Houvenaeghel G, Delpero JR, Guerinel G. Incidence and management of major urinary complications after pelvic exenteration for gynecological malignancies. Journal of Surgical Oncology. 1995;58:91-96.

Browning A. Lack of value of the Martius graft in obstetric fistula repair. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 2006;93:33-37.

Browning A. Risk factors for developing residual urinary incontinence after obstetric fistula repair. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2006;113:482-485.

Browning A. Pregnancy following obstetric fistula repair, the management of delivery. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2009;116:1265-1267.

Browning A, Fentahun W, Goh JT. The impact of surgical treatment on the mental health of women with obstetric fistula. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2007;114:1439-1441.

Browning A, Menber B. Women with obstetric fistula in Ethiopia: a 6-month follow up after surgical treatment. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2008;115:1564-1569.

Bruce RG, El-Galley RES, Galloway NTM. Use of rectus abdominis muscle flap for the treatment of complex and refractory urethrovaginal fistulas. Journal of Urology. 2000;163:1212-1215.

Chang R, Marshall F, Mitchell S. Percutaneous management of benign ureteral strictures and fistulas. Journal of Urology. 1987;137:1126-1131.

Chassar Moir J. The Vesico-vaginal Fistula, 2nd edn. London: Baillière; 1967.

Chassar Moir J. Vesico-vaginal fistulae as seen in Britain. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology of the British Commonwealth. 1973;80:598-602.

Davits R, Miranda S. Conservative treatment of vesico-vaginal fistulas by bladder drainage alone. British Journal of Urology. 1991;68:155-156.

Department of Health. Hospital Episode Statistics. Department of Health. Available at www.hesonline.nhs.uk, 2009.

Dolan L, Dixon W, Hilton P. Urinary symptoms and quality of life following urogenital fistula repair: a long-term follow-up study. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2008;115:1570-1574.

Elkins TE, Drescher C, Martey JO, Fort D. Vesicovaginal fistula revisited. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1988;72:307-312.

Emmert C, Köhler U. Management of genital fistulas in patients with cervical cancer. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 1996;259:19-24.

Falk F, Tancer M. Management of vesical fistulas after caesarean section. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1956;71:97-106.

Goh J. A new classification for female genital tract fistula. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2004;44:502-504.

Goh JT, Browning A, Berhan B, Chang A. Predicting the risk of failure of closure of obstetric fistula and residual urinary incontinence using a classification system. International Urogynecology Journal of Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. 2008;19:1659-1662.

Goodwin WE, Scardino PT. Vesicovaginal and ureterovaginal fistulas: a summary of 25 years of experience. Transactions of the American Association of Genitourinary Surgeons. 1979;71:123-129.

Hamlin R, Nicholson E. Reconstruction of urethra totally destroyed in labour. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 1969;2:147-150.

Harkki-Siren P, Sjoberg J, Tiitinen A. Urinary tract injuries after hysterectomy. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1998;92:113-118.

Hilton P. Catheters and drains. In: Stanton S, editor. Principles of Gynaecological Surgery. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1987:257-283.

Hilton P. Surgery for genuine stress incontinence: which operation and for which patient? In: Drife J, Hilton P, Stanton S, editors. Micturition—Proceedings of the 21st RCOG Study Group. London: Springer-Verlag; 1990:225-246.

Hilton P. Sims to SMIS—an Historical Perspective on Vesico-vaginal Fistulae. The Yearbook of the RCOG, 1994. London: Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists; 1995. pp 7–16

Hilton P. Debate: ‘Post-operative urinary fistulae should be managed by gynaecologists in specialist centres’. BJU International. 1997;80(Suppl 1):35-42.

Hilton P. The urodynamic findings in patients with urogenital fistulae. British Journal of Urology. 1998;81:539-542.

Hilton P, Ward A. Epidemiological and surgical aspects of urogenital fistulae: a review of 25 years experience in south-east Nigeria. International Urogynecology Journal and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. 1998;9:189-194.

Hilton P, Ward A, Molloy M, Umana O. Periurethral injection of autologous fat for the treatment of post-fistula repair stress incontinence: a preliminary report. International Urogynecology Journal and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. 1998;9:118-121.

Hudson C. Malignant change in an obstetric vesico-vaginal fistula. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine. 1968;61:121-124.

Hudson C, Hendrickse J, Ward A. An operation for restoration of urinary continence following total loss of the urethra. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1975;82:501-504.

Iselin CE, Aslan P, Webster GD. Transvaginal repair of vesicovaginal fistulas after hysterectomy by vaginal cuff excision. Journal of Urology. 1998;160:728-730.

Jonas U, Petri E. Genitourinary fistulae. In: Stanton S, editor. Clinical Gynecologic Urology. St Louis: CV Mosby; 1984:238-255.

Kelly J. Vesicovaginal fistulae. British Journal of Urology. 1979;51:208-210.

Kelly J. Vesico-vaginal fistulae. In: Studd J, editor. Progress in Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 3rd edn. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1983:324-333.

Kelly J, Kwast B. Epidemiologic study of vesico-vaginal fistula in Ethiopia. International Urogynecology Journal. 1993;4:278-281.

Kiricuta I. Use of the greater omentum in the treatment of vesicovaginal and rectovesicovaginal fistulae after radiotherapy and cystoplasties [in French]. Journal de Chirurgie. 1965;89:477-484.

Kiricuta I, Goldstein A. The repair of extensive vesicovaginal fistulas with pedicled omentum: a review of 27 cases. Journal of Urology. 1972;108:724-727.

Lawson J. Injuries to the urinary tract. In: Lawson J, Stewart D, editors. Obstetrics and Gynaecology in the Tropics and Developing Countries. London: Edward Arnold; 1967:481-522.

Lawson J. Vesical fistulae into the vaginal vault. British Journal of Urology. 1972;44:623-631.

Lawson J. The management of genito-urinary fistulae. Clinics in Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1978;6:209-236.

Lawson L, Hudson C. The management of vesico-vaginal and urethral fistulae. In: Stanton S, Tanagho E, editors. Surgery for Female Urinary Incontinence. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1987:193-209.

Lee R, Symmonds R, Williams T. Current status of genitourinary fistula. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1988;71:313-319.

Lovel H, McGettigan C, Mohammed Z. A Systematic Review of the Health Complications of Female Genital Mutilation Including Sequelae in Childbirth. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2000.

Meeks GR, Sams JO, Field KW, Fulp KS, Margolis MT. Formation of vesicovaginal fistula: the role of suture placement into the bladder during closure of the vaginal cuff after transabdominal hysterectomy. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1997;177:1298-1304.

Mundy A. Urodynamic and Reconstructive Surgery of the Lower Urinary Tract. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1993.

Murphy M. Social consequences of vesico-vaginal fistula in northern Nigeria. Journal of Biosocial Sciences. 1981;13:139-150.

Nardos R, Browning A, Member B. Duration of bladder catheterization after surgery for obstetric fistula. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 2008;103:30-32.

Nielsen H, Lindberg L, Nygaard U, et al. A community based long-term follow-up of obstetric fistula patients in rural Ethiopia. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2009;116:1258-1264. 2009

O’Conor VJ. Review of experience with vesicovaginal fistula repair. Journal of Urology. 1980;123:367-369.

Patil U, Waterhouse K, Laungani G. Management of 18 difficult vesicovaginal and urethrovaginal fistulas with modified Ingelman-Sundberg and Martius operations. Journal of Urology. 1980;123:653-656.

Raghavaiah N. Double-dye test to diagnose various types of vaginal fistulas. Journal of Urology. 1974;112:811-812.

Rangnekar NP, Imdad AN, Kaul SA, Pathak HR. Role of the Martius procedure in the management of urinary-vaginal fistulas. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2000;191:259-263.

Schwartz BF, Stoller ML. Endourologic management of urinary fistulae. Techniques in Urology. 2000;6:193-195.

Sims J. On the treatment of vesico-vaginal fistula. American Journal of Medical Sciences. 1852;XXIII:59-82.

Sultan AH, Kamm MA, Hudson CN, Bartram CI. Third degree obstetric and sphincter tears: risk factors and outcome of primary repair. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 1994;308:887-891.

Tahzib F. Epidemiological determinants of vesicovaginal fistulas. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1983;90:387-391.

Tahzib F. Vesicovaginal fistula in Nigerian children. The Lancet. 1985;2:1291-1293.

Tomlinson AJ, Thornton JG. A randomised controlled trial of antibiotic prophylaxis for vesico-vaginal fistula repair. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1998;105:397-399.

Turner-Warwick R. The use of the omental pedicle graft in urinary tract reconstruction. Journal of Urology. 1976;116:341-347.

Turner-Warwick RT, Wynne EJ, Handley-Ashken M. The use of the omental pedicle graft in the repair and reconstruction of the urinary tract. British Journal of Surgery. 1967;54:849-853.

United Nations Population Fund. A Holistic Approach to the Abandonment of Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting. New York: UNFPA; 2007. Available at www.unfpa.org/webdav/site/global/shared/documents/publications/2007/726_filename_fgm.pdf

Waaldijk K 1989 The Surgical Management of Bladder Fistula in 775 Women in Northern Nigeria. MD Thesis, Amsterdam. Benda B.V., Nijmegen, The Netherlands.

Waaldijk K. The immediate surgical management of fresh obstetric fistulas with catheter and/or early closure. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 1994;45:11-16.

Waaldijk K. Step-by-step Surgery for Vesico-vaginal Fistulas. Edinburgh: Campion; 1994.

Waaldijk K. Surgical classification of obstetric fistulas. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 1995;49:161-163.

Waaldijk K. Immediate indwelling bladder catheterisation at postpartum urine leakage—personal experience of 1200 patients. Tropical Doctor. 1997;27:227-228.

Waaldijk K, Armiya’u Y. The obstetric fistula: a major public health problem still unsolved. International Urogynecology Journal. 1993;4:126-128.

Waaldijk K, Elkins T. The obstetric fistula and perineal nerve injury: an analysis of 947 consecutive patients. International Urogynecology Journal. 1994;5:12-14.

Wein AJ, Malloy TR, Carpiniello VL, Greenberg SH, Murphy JJ. Repair of vesicovaginal fistula by a suprapubic transvesical approach. Surgery, Gynecology and Obstetrics. 1980;150:57-60.

World Health Organization. The Prevention and Treatment of Obstetric Fistulae: a Report of a Technical Working Group. Geneva: WHO; 1989.

World Health Organization. Eliminating Female Genital Mutilation: an Interagency Statement: UNAIDS, UNDP, UNECA, UNESCO, UNFPA, UNHCHR, UNHCR, UNICEF, UNIFEM, WHO. Geneva: WHO; 2008. Available at www.who.int/reproductive-health/publications/fgm/fgm_statement_2008.pdf

Yeates W. Uretero-vaginal fistulae. In: Stanton S, Tanagho E, editors. Surgery for Female Urinary Incontinence. 2nd edn. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1987:211-217.

Youssef A. ‘Menouria’ following lower segment caesarean section: a syndrome. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1957;73:759-767.

Zacharin R. Obstetric Fistula. Vienna: Springer-Verlag; 1988.