Fibrous tumors

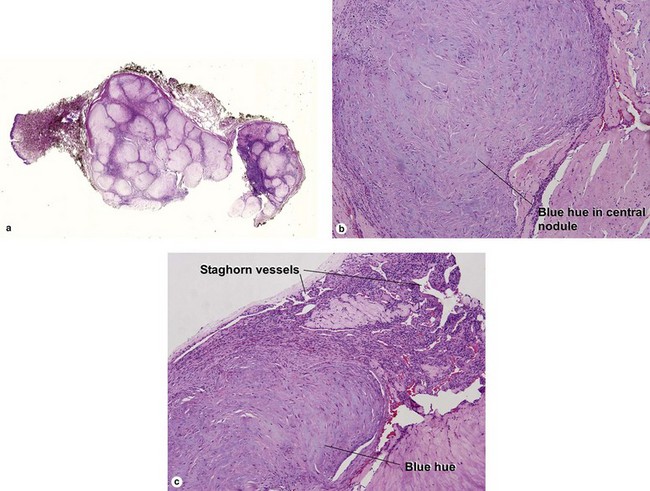

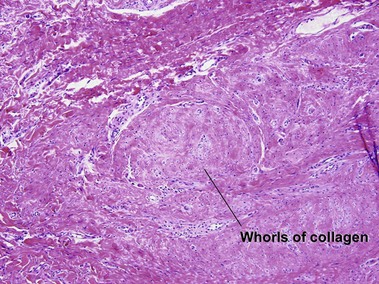

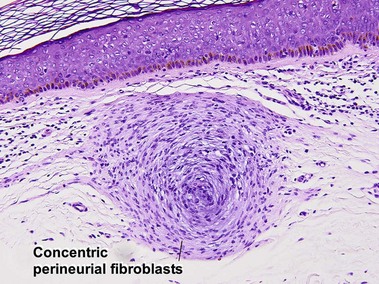

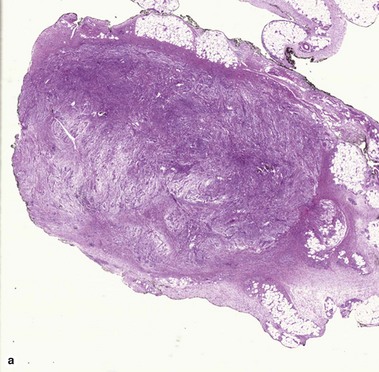

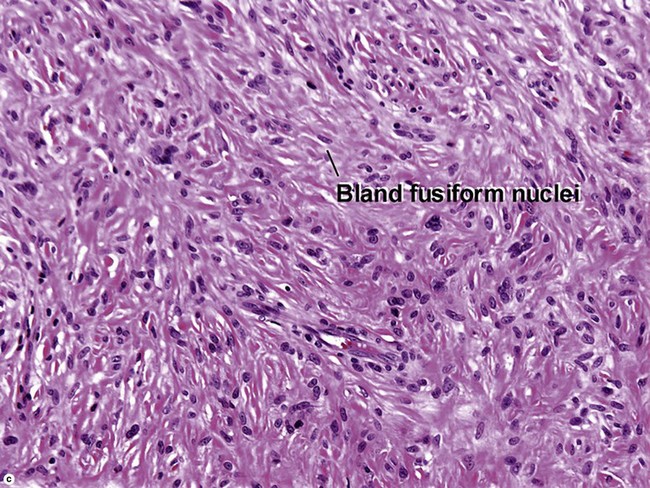

Adult myofibroma

The shade of blue in the center of the nodule resembles that of cartilage. The peripheral vascular proliferation may have staghorn vessels and resemble hemangiopericytoma.

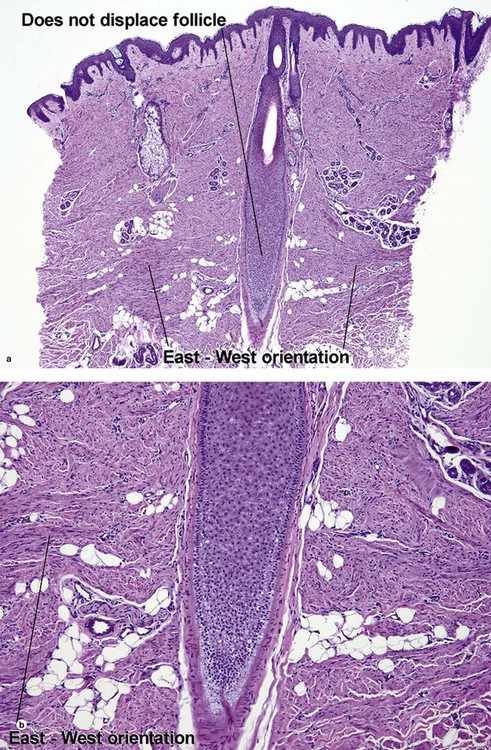

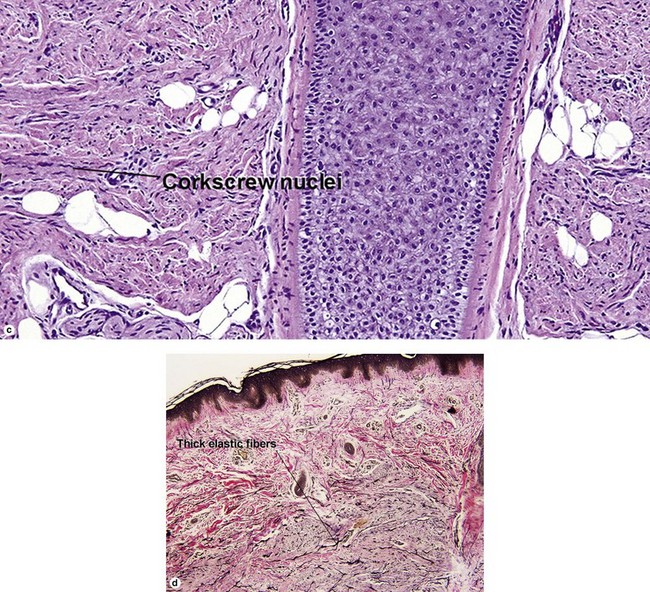

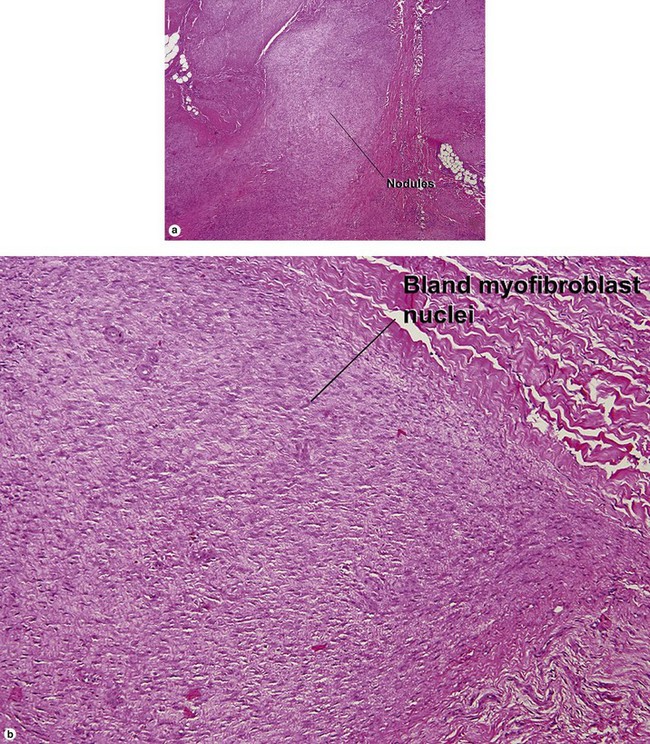

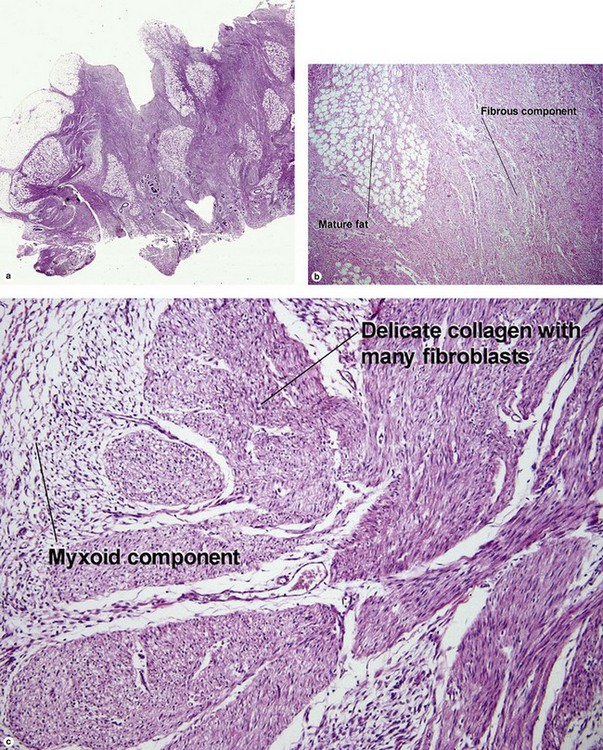

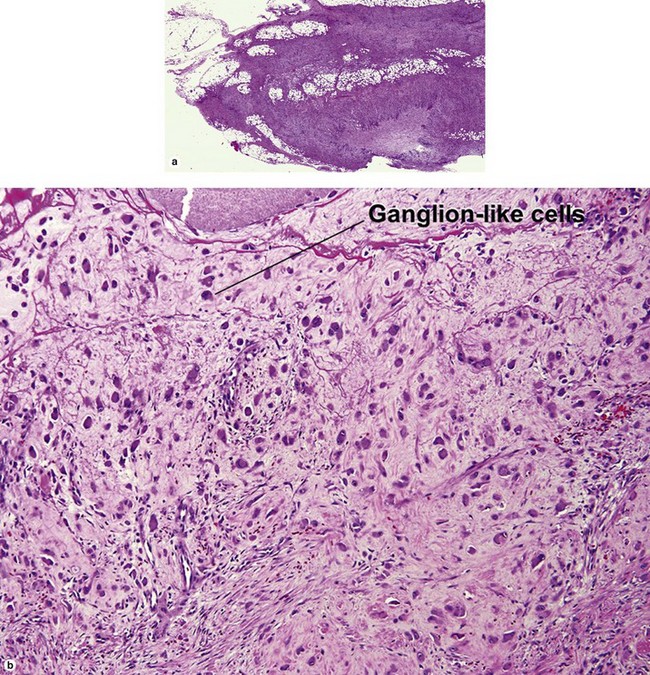

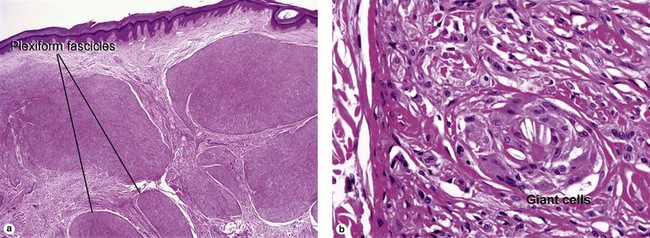

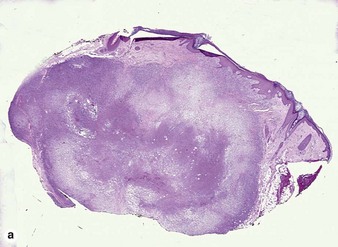

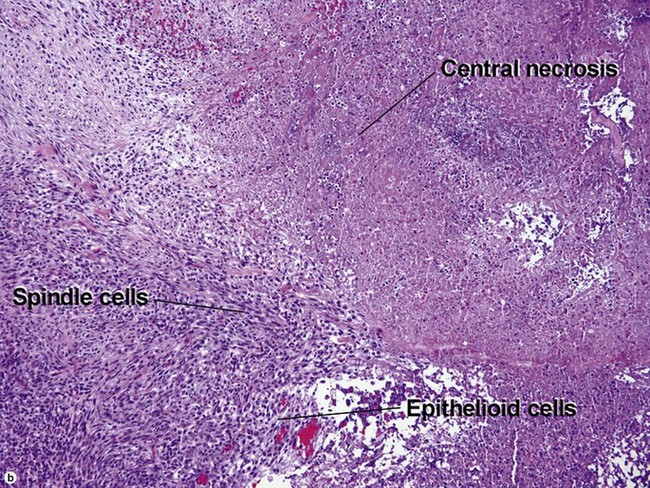

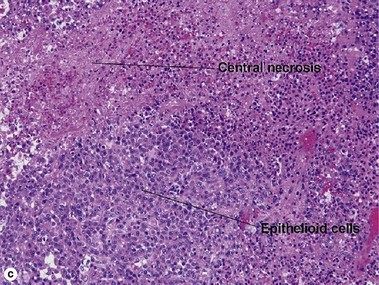

Infantile myofibromatosis

There is a tendency towards spontaneous regression. Superficial disease has an excellent prognosis. Visceral involvement may be fatal in some cases. In one series, more than half of the lesions were present at or soon after birth, approximately 80% were solitary, and 50% involved the head and neck. In the early stage, undifferentiated immature histiocytic cells may predominate. As the lesion matures, they develop characteristics of myofibroblasts. Regressing lesions become progressively less cellular and more fibrous.

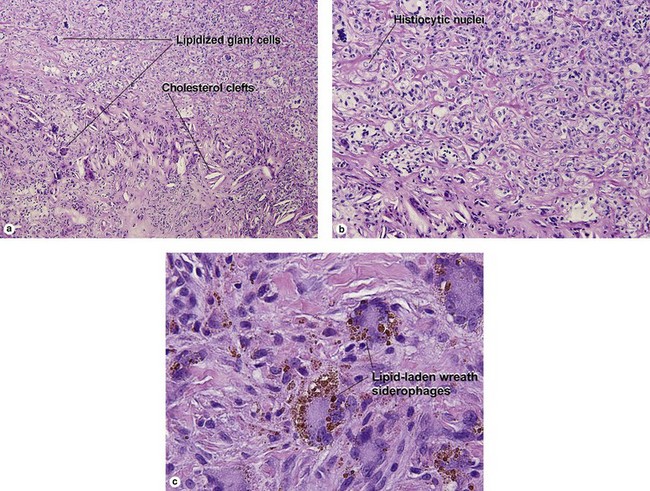

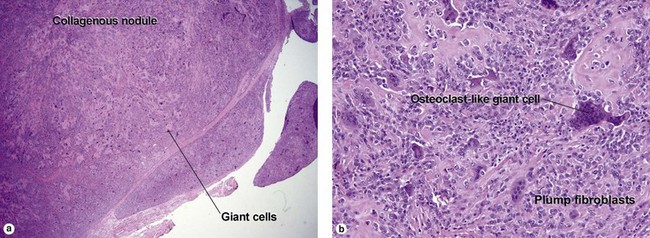

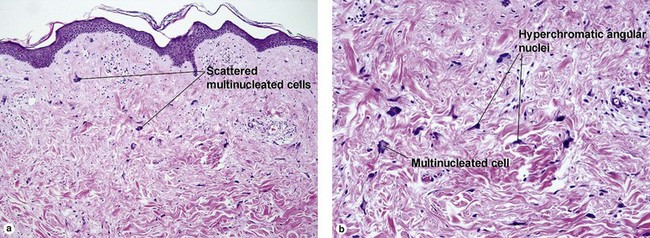

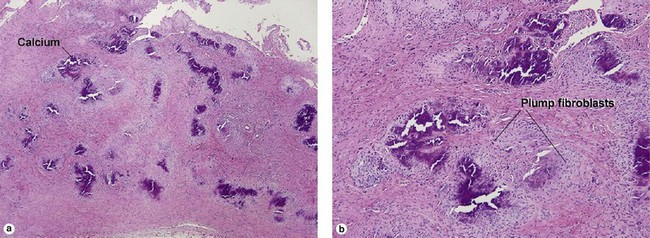

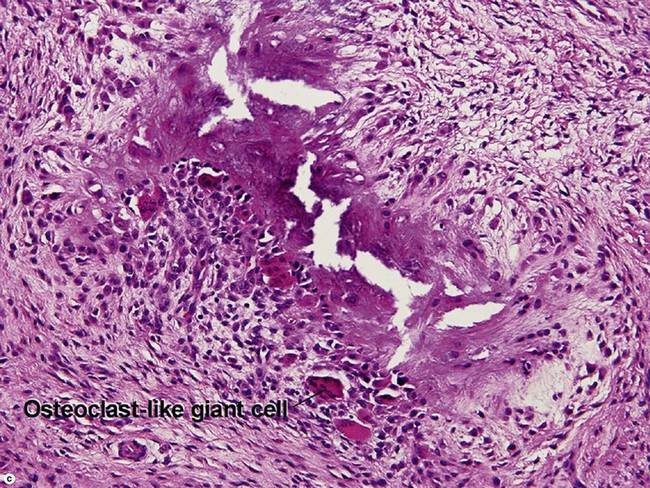

Giant cell tumor of the tendon sheath

Osteoclast-like giant cells have randomly distributed nuclei. The cytoplasm stains deeply pink to amphophilic and has scalloped edges where the cell exhibits molding against adjoining tissue.

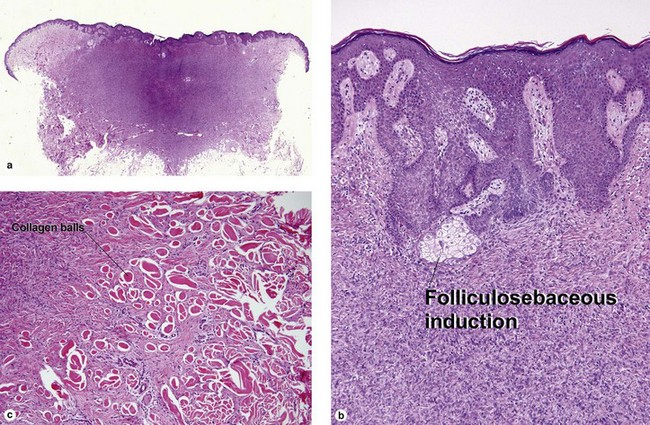

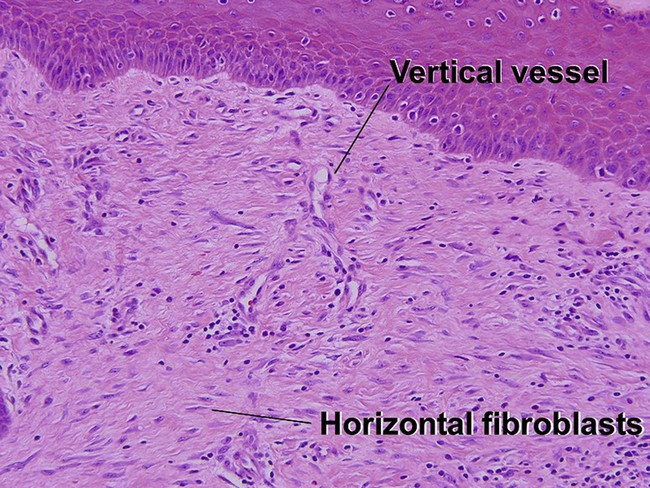

Angiofibromas

In tuberous sclerosis, we call them adenoma sebaceum or Koenen’s periungual fibromas. Multiple angiofibromas may also be seen in multiple endocrine neoplasia type I (MEN 1) and in type II neurofibromatosis.

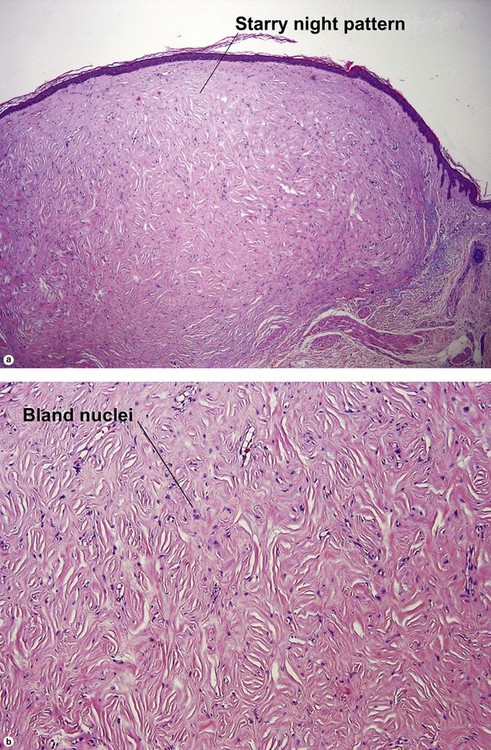

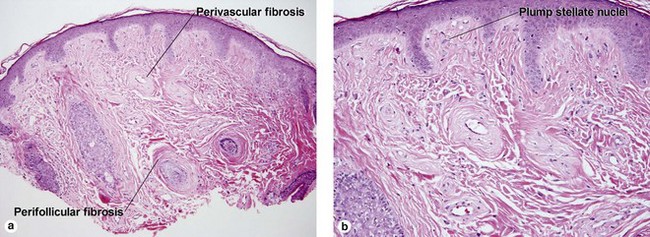

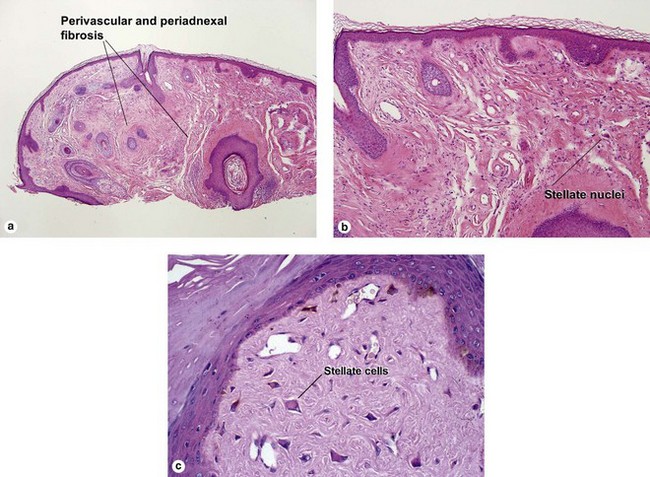

Fibrous papule of the face (benign fibrous papule, solitary angiofibroma)

A superficial shave biopsy of a fibrous papule may suggest a melanocytic lesion, because of the large melanocytes at the dermal–epidermal junction. Before the advent of immunostains, the stellate dermal cells were thought to be degenerated melanocytes.

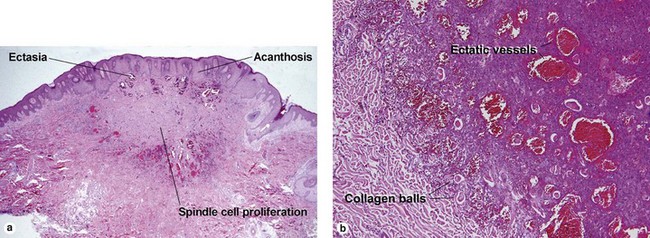

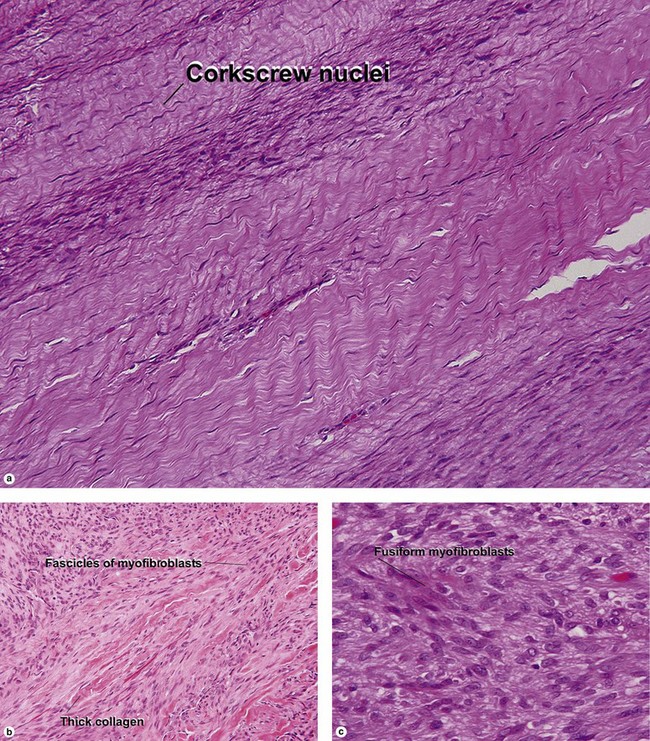

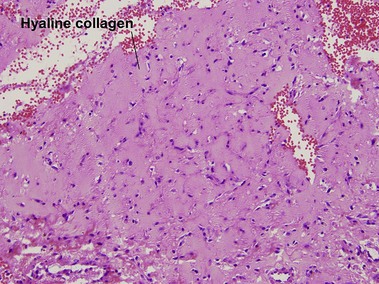

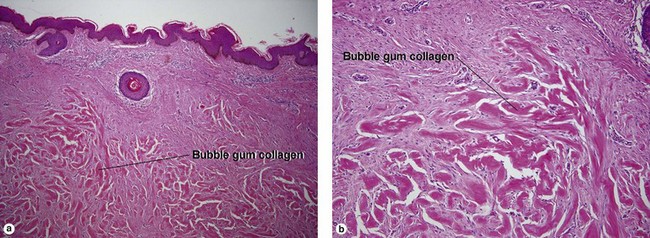

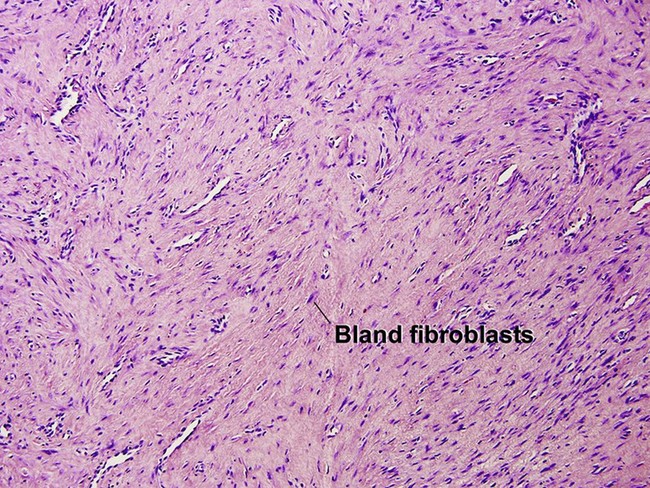

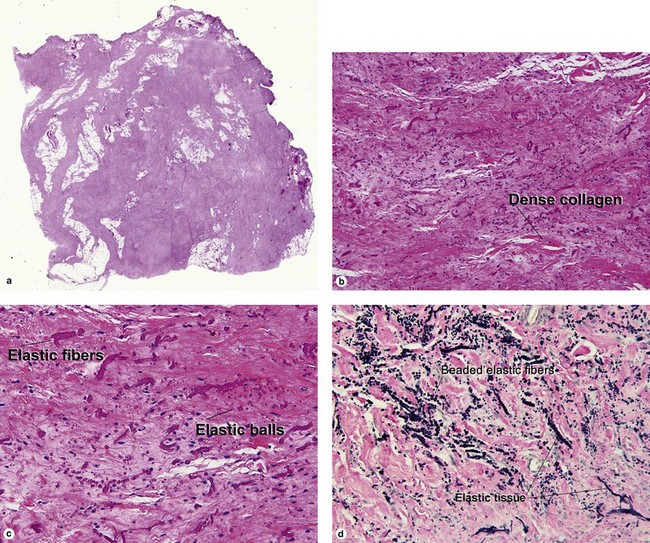

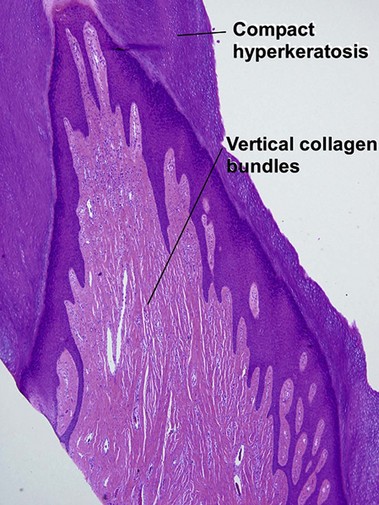

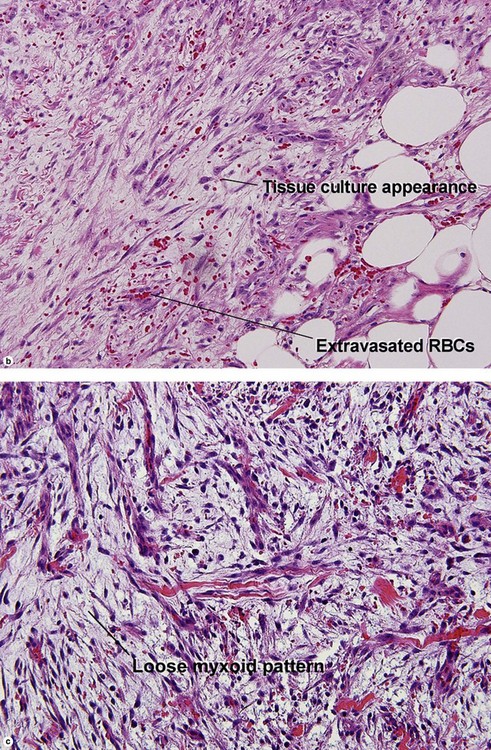

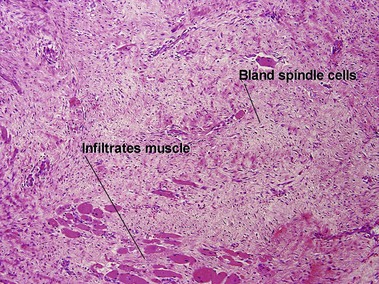

Nodular fasciitis

With time, nodular fasciitis develops thick red collagen bundles, but young lesions appear loose and myxoid, with erythrocyte extravasation and nodular aggregates of inflammatory cells. The stellate fibroblasts look like those in tissue culture.

Malignant tumors

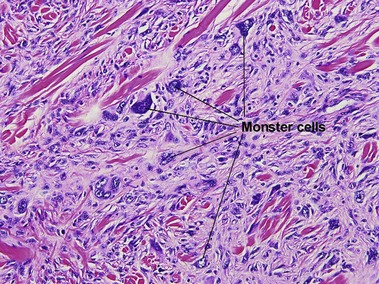

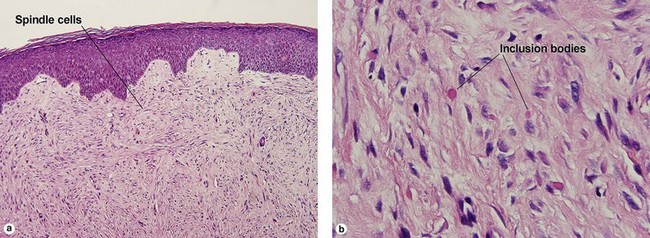

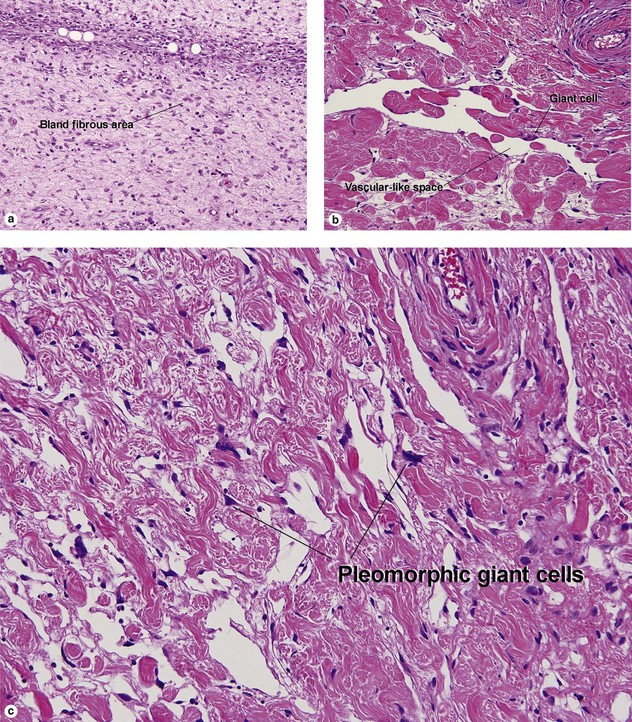

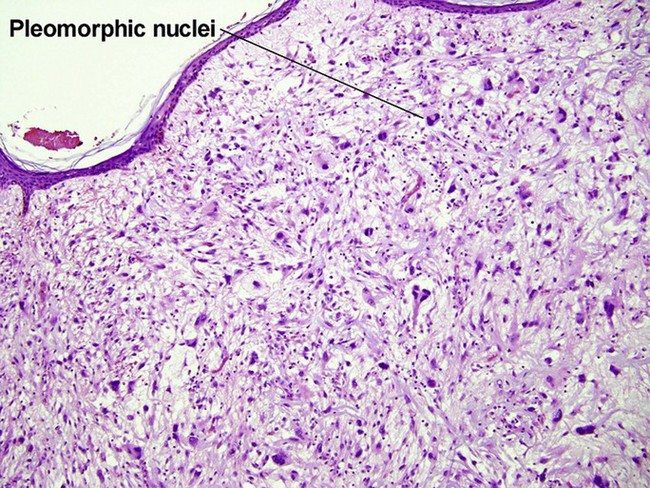

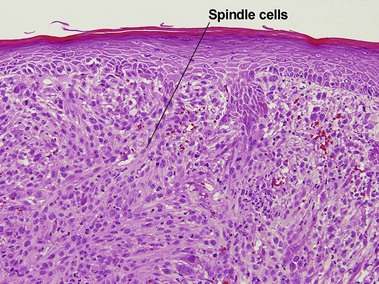

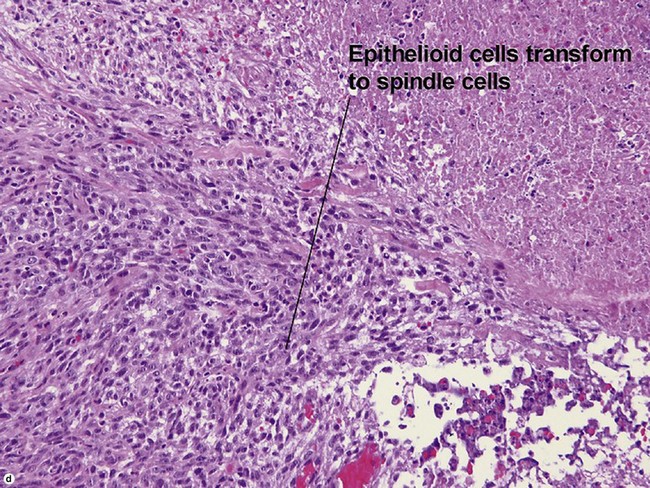

Atypical fibroxanthoma (AFX)

Some consider atypical fibroxanthoma to be a superficial variant of pleomorphic undifferentiated sarcoma.

Baerg, J, Murphy, JJ, Magee, JF. Fibromatoses: clinical and pathological features suggestive of recurrence. J Pediatr Surg. 1999; 34(7):1112–1114.

Billings, SD, Folpe, AL. Cutaneous and subcutaneous fibrohistiocytic tumors of intermediate malignancy: an update. Am J Dermatopathol. 2004; 26(2):141–155.

Clarke, LE. Fibrous and fibrohistiocytic neoplasms: an update. Dermatol Clin. 2012; 30(4):643–656.

Franchi, A, Santucci, M. The contribution of electron microscopy to the characterization of soft tissue fibrosarcomas. Ultrastruct Pathol. 2013; 37(1):9–14.

Iijima, S, Suzuki, R, Otsuka, F. Solitary form of infantile myofibromatosis: a histologic, immunohistochemical, and electron microscopic study of a regressing tumor over a 20-month period. Am J Dermatopathol. 1999; 21(4):375–380.

Mahmood, MN, Salama, ME, Chaffins, M, et al. Solitary sclerotic fibroma of skin: a possible link with pleomorphic fibroma with immunophenotypic expression for O13 (CD99) and CD34. J Cutan Pathol. 2003; 30(10):631–636.

Martín-López, R, Feal-Cortizas, C, Fraga, J. Pleomorphic sclerotic fibroma. Dermatology. 1999; 198(1):69–72.

Parish, LC, Yazdanian, S, Lambert, WC, et al. Dermatofibroma: a curious tumor. Skinmed. 2012; 10(5):268–270.

Stanford, D, Rogers, M. Dermatological presentations of infantile myofibromatosis: a review of 27 cases. Australas J Dermatol. 2000; 41(3):156–161.

Tani, M, Komura, A, Ichihashi, M. Dermatomyofibroma (Plaqueformige Dermale Fibromatose). J Dermatol. 1997; 24(12):793–797.

Terrier-Lacombe, MJ, Guillou, L, Maire, G, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, giant cell fibroblastoma, and hybrid lesions in children: clinicopathologic comparative analysis of 28 cases with molecular data – a study from the French Federation of Cancer Centers Sarcoma Group. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003; 27(1):27–39.