Chapter 18 FEVER OF UNKNOWN ORIGIN

General Discussion

Petersdorf and Beeson10 defined fever of unknown origin (FUO) as fever persisting for longer than 3 weeks, a documented temperature of greater than 101° F (38.3° C) on several occasions, and an uncertain diagnosis after intensive study for at least 1 week. Subsequently, in 1968 Dechovitz and Moffet2 defined FUO in children as fever lasting longer than 2 weeks for which no diagnosis could be made. With the advent of more advanced diagnostic modalities, a more contemporary definition in children is a minimum of 14 days of daily documented temperature of 38.3° C or greater without apparent cause, after performance of repeated physical examinations and screening laboratory tests.

Causes of FUO

Primary immunodeficiency diseases usually present with repeated infections; however, prolonged fever can be the presenting manifestation before a definite infection has been identified.

• Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura

• Infantile-onset multisystem inflammatory disease

• Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis

• Mixed connective tissue disease

Key Physical Findings

Growth curve plots of height and weight

Growth curve plots of height and weight

General assessment of overall health

General assessment of overall health

Ocular and funduscopic examination: pupillary response to light can be impaired in CNS dysfunction; vasculitic lesions may be seen on fundoscopic exam. Disseminated tuberculosis (TB) or toxoplasmosis can produce funduscopic abnormalities. Conjunctivitis is present in a number of illnesses: bulbar conjunctivitis may be seen in infectious mononucleosis, lupus erythematosus may present with palpebral conjunctivitis, and Kawasaki disease can have a predominantly bulbar conjunctivitis.

Ocular and funduscopic examination: pupillary response to light can be impaired in CNS dysfunction; vasculitic lesions may be seen on fundoscopic exam. Disseminated tuberculosis (TB) or toxoplasmosis can produce funduscopic abnormalities. Conjunctivitis is present in a number of illnesses: bulbar conjunctivitis may be seen in infectious mononucleosis, lupus erythematosus may present with palpebral conjunctivitis, and Kawasaki disease can have a predominantly bulbar conjunctivitis.

Oropharyngeal examination: pharyngeal hyperemia without exudates may be associated with EBV, CMV, toxoplasmosis, tularemia, or leptospirosis infections. Loss of teeth and gingival hypertrophy can be a sign of leukemia or Langerhans histocytosis. The presence of aphthous stomatitis may indicate lupus, mixed connective tissue disease, or vasculitis.

Oropharyngeal examination: pharyngeal hyperemia without exudates may be associated with EBV, CMV, toxoplasmosis, tularemia, or leptospirosis infections. Loss of teeth and gingival hypertrophy can be a sign of leukemia or Langerhans histocytosis. The presence of aphthous stomatitis may indicate lupus, mixed connective tissue disease, or vasculitis.

Neck examination for cervical lymphadenopathy

Neck examination for cervical lymphadenopathy

Cardiovascular examination for friction rubs or prominent or new murmurs

Cardiovascular examination for friction rubs or prominent or new murmurs

Pulmonary examination for rales or consolidation

Pulmonary examination for rales or consolidation

Abdominal examination for masses, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, or focal tenderness

Abdominal examination for masses, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, or focal tenderness

Pelvic examination in adolescent females for cervical discharge, cervical motion tenderness, or adnexal tenderness

Pelvic examination in adolescent females for cervical discharge, cervical motion tenderness, or adnexal tenderness

Musculoskeletal examination for gait, assessment of strength, point tenderness over the bones, joint tenderness, joint effusion, or limited range of motion in the joints. Each joint should be evaluated for swelling, warmth, redness, and range of motion. Long bones must be palpated carefully for bony tenderness. The spine should be palpated and assessed for range of motion.

Musculoskeletal examination for gait, assessment of strength, point tenderness over the bones, joint tenderness, joint effusion, or limited range of motion in the joints. Each joint should be evaluated for swelling, warmth, redness, and range of motion. Long bones must be palpated carefully for bony tenderness. The spine should be palpated and assessed for range of motion.

Skin examination for rash, petechiae, jaundice (hepatitis, malaria), seborrhea (histoplasmosis), erythrema nodosum (Coccidioides immitis), changes in dermal thickness, tightening or contractures, pigmentation changes, nail changes, or alopecia.

Skin examination for rash, petechiae, jaundice (hepatitis, malaria), seborrhea (histoplasmosis), erythrema nodosum (Coccidioides immitis), changes in dermal thickness, tightening or contractures, pigmentation changes, nail changes, or alopecia.

Rectal examination for bloody stool or lesions

Rectal examination for bloody stool or lesions

Neurologic examination for focal deficits, changes in mental status, ataxia, or seizure activity

Neurologic examination for focal deficits, changes in mental status, ataxia, or seizure activity

Initial Work-Up

| Complete blood cell count (CBC) with differential and platelet count | To evaluate for leukocytosis (infection or rheumatologic disease), leukemia, or thrombocytopenia |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) | To evaluate for inflammatory processes |

| Electrolytes | To evaluate for metabolic derangements such as acidosis |

| Urinalysis and urine culture | To evaluate for cystitis, pyelonephritis, or inflammatory nephritis |

| Liver function tests | To screen for hepatitis |

| Hepatitis screening tests | To evaluate for viral hepatitis |

| Blood cultures | To evaluate for bacteremia and subacute bacterial endocarditis |

| Streptococcal enzyme titers | To evaluate for exposure to Streptococcus spp. |

| Lyme titers | To evaluate for Lyme disease, especially in endemic areas or if there is a history of travel to an endemic area |

| Antinuclear antibody | To evaluate for rheumatologic processes |

| Purified protein derivative (PPD) | To evaluate for exposure to TB |

| Chest radiograph | To evaluate for cardiac and pulmonary disease |

Additional Work-Up

| C-reactive protein | If an inflammatory process is suspected, as an alternative test to the ESR |

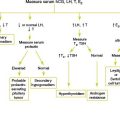

| Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) and thyroxine (T4) | If thyrotoxicosis is suspected |

| Stool cultures | If enteritis or typhoid fever is suggested by history |

| Total protein and albumin | To evaluate nutritional status and hepatic synthetic function |

| IgG, IgM, and IgA | If immunodeficiency is suspected |

| IgD | To evaluate for hyperimmunoglobulin D syndrome |

| Rheumatoid factor | If juvenile rheumatoid arthritis is suspected |

| HIV test | If HIV infection is suspected |

| EBV titers | If EBV infection is suspected |

| CMV screening | If CMV infection is suspected |

| Urine vanillylmandelic acid (VMA) and metanephrines | If pheochromocytoma is suspected |

| Stool guaiac testing | If enteritis is suspected |

| Sweat chloride test | If cystic fibrosis is suspected |

| Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) | To evaluate for syphilis |

| Lumbar puncture with Gram stain, cell counts, cultures, and viral studies | If CNS infection or inflammation is suspected. |

| Bartonella titer | If cat-scratch disease is suspected |

| Toxoplasmosis titer | If toxoplasmosis is suspected |

| Rickettsia titer | If Rickettsial infection is suspected |

| Francisella titer | If tularemia is suspected |

| Coxiella titer | If Q fever is suspected |

| Candida skin test | To test cellular immunity if primary immunodeficiency is suspected |

| Synovial fluid analysis evaluation | If a single joint is swollen |

| Synovial biopsy | If a single joint is swollen and the tuberculin test is positive to evaluate for tuberculous arthritis |

| Lymph node biopsy | If persistent lymphadenopathy is present and a diagnosis has not been determined |

| Bone marrow biopsy | If an oncologic process or bone marrow infiltrative process is suspected |

| Bone biopsy | If a bony lesion is found on imaging study |

| B-lymphocyte quantification and antibody titers against protein antigens such as tetanus | To test humoral immunity if primary immunodeficiency is suspected |

| Total hemolytic complement levels | If congenital complement deficiency is suspected |

| Thick and thin smears for malaria | If malaria is suspected |

Imaging Studies

| Electrocardiogram (ECG) and echocardiogram | If endocarditis, myocarditis, or pleural effusion is suspected |

| Radiographs of specific bones | If osteomyelitis or tumor is suspected |

| Sinus x-rays or computed tomography (CT) | If sinusitis is suspected |

| Bone scan | To evaluate for osteomyelitis or juvenile arthritis |

| CT scan of the abdomen | To evaluate for intra abdominal abscess or tumor |

| Abdominal ultrasound | To evaluate for intra abdominal abscess or tumor |

| Gallium scan | To evaluate for intra abdominal abscess or tumor |

| CT scan of the chest | If thoracic pathology is suspected |

| CT scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain | If CNS tumor or abscess is suspected |

| Electroencephalography | If encephalitis is suspected |

| MRI of the spine | To evaluate for tumor, abscess, or diskitis |

| MRI of the abdomen | To evaluate for abscess |

| Vesicoureterogram or intravenous pyelogram | If urinary tract pathology is suspected |

| Barium enema | If colonic pathology is suspected |

| Colonoscopy with biopsy | If inflammatory bowel disease is suspected |

1. Baraff L.J. Management of fever without source in infants and children. Ann Emerg Med. 2000;36:602–614.

2. Dechovitz A.B., Moffet H.L. Classification of acute febrile illnesses in childhood. Clin Pediatr. 1968;7:649–653.

3. Finkelstein J.C., Christiansen C.L., Platt R. Fever in pediatric primary care: occurrence, management, and outcomes. Pediatrics. 2000;105:260–265.

4. Ishimine P. Fever without source in children 0 to 36 months of age. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2006;53:167–194.

5. Jacobs R.F., Schutze G.E. Bartonella henselae as a cause of prolonged fever and fever of unknown origin in children. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:80–84.

6. Miller L., Sisson B.A., Tucker L.B., Schaller J.G. Prolonged fevers of unknown origin in children: patterns of presentation and outcome. J Pediatr. 1996;12:419–421.

7. Miller M.L., Szer I., Yogev R., Bernstein B. Fever of unknown origin. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1995;42:999–1015.

8. Padeh S. Periodic fever syndromes. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2005;52:577–609.

9. Palazzi D.L., McClain K.L., Kaplan S.L. Hemophagocytic syndrome in children: an important diagnostic consideration in fever of unknown origin. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:306–312.

10. Petersdorf R.G., Beeson P.B. Fever of unexplained origin: report on 100 cases. Medicine (Baltimore). 1961;40:1–30.