Chapter 17 Female Genitalia and the Pelvis

2 How can I make my patient as comfortable as possible during the pelvic exam?

By following a few simple steps:

Instruct her to void prior to the exam, since a full bladder can often be confused for a pregnant uterus or an ovarian cyst.

Instruct her to void prior to the exam, since a full bladder can often be confused for a pregnant uterus or an ovarian cyst.

Ideally have her empty her bowels, too.

Ideally have her empty her bowels, too.

Raise the table back to a comfortable height so that you can maintain eye contact at all time.

Raise the table back to a comfortable height so that you can maintain eye contact at all time.

Place a drape over her abdomen, thighs, and knees.

Place a drape over her abdomen, thighs, and knees.

Before performing each step of the exam, inform her about it.

Before performing each step of the exam, inform her about it.

Instruct her to relax the perineal muscles through appropriate breathing.

Instruct her to relax the perineal muscles through appropriate breathing.

Always wash your hands in the presence of the patient.

Always wash your hands in the presence of the patient.

Warm the speculum before using it.

Warm the speculum before using it.

Watch your terminology during the exam. Never say you are going to “feel” something since this has sexual connotations. Use instead “check.” Also, do not refer to “foot rests” as “stirrups.” And more importantly, keep them out of sight until you are ready to use them.

Watch your terminology during the exam. Never say you are going to “feel” something since this has sexual connotations. Use instead “check.” Also, do not refer to “foot rests” as “stirrups.” And more importantly, keep them out of sight until you are ready to use them.

Always explain your findings, even if normal.

Always explain your findings, even if normal.

Continuous communication is paramount. Provide your patient with a sense of control by reassuring her that she will be able to stop the exam at any time if it were to become too uncomfortable. Also, offer her a hand-held mirror so that she can become more of a participant. By following these guidelines, pelvic exams should cause minimal discomfort or embarrassment. They should never be painful, except for tenderness from underlying pathology.

Continuous communication is paramount. Provide your patient with a sense of control by reassuring her that she will be able to stop the exam at any time if it were to become too uncomfortable. Also, offer her a hand-held mirror so that she can become more of a participant. By following these guidelines, pelvic exams should cause minimal discomfort or embarrassment. They should never be painful, except for tenderness from underlying pathology.

7 What are the tools needed for a pelvic exam?

Padded exam table with padded foot rests (quilted oven mitts do nicely)

Padded exam table with padded foot rests (quilted oven mitts do nicely)

Good and adjustable light source (gooseneck or fiberoptic lamp)

Good and adjustable light source (gooseneck or fiberoptic lamp)

Plastic (or metal) vaginal specula of various sizes and types, including Pedersen’s, Graves’, and pediatric

Plastic (or metal) vaginal specula of various sizes and types, including Pedersen’s, Graves’, and pediatric

Although a simple direct exam can provide lots of information, a few bedside diagnostic procedures are routinely added. These include occult blood testing, microbiologic assessment, and performance of the Papanicolaou smear (which provides a simple cytologic exam for cervical inflammation, atypia, or dysplasia). To carry out these procedures you will need:

Although a simple direct exam can provide lots of information, a few bedside diagnostic procedures are routinely added. These include occult blood testing, microbiologic assessment, and performance of the Papanicolaou smear (which provides a simple cytologic exam for cervical inflammation, atypia, or dysplasia). To carry out these procedures you will need:

A. Inspection/Palpation of External Genitalia: Vulva and Perineum

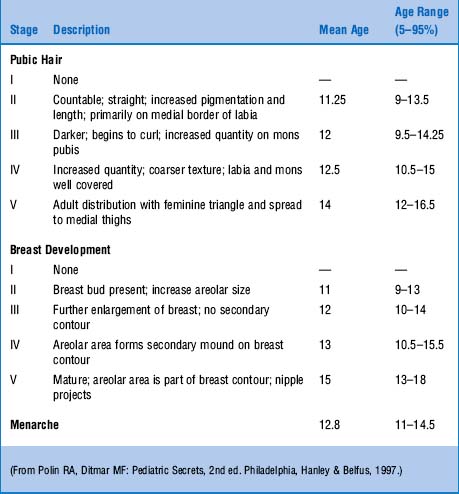

15 What are Tanner’s stages of sexual maturation?

They are a way to assess sexual maturation by following the growth of breast and pubic hair. They are mostly used in pediatric and adolescent medicine, but also can be helpful in evaluating patients with primary amenorrhea (Table 17-1).

18 What are the benign white lesions of the vulva?

They are mostly vitiligo and inflammatory dermatitis, like psoriasis.

20 What are malignant white lesions?

Mostly two: vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia and Bowen’s disease.

25 Where are Bartholin’s glands located?

Deep in the lateral walls of the vulva, close to the posterior fornix.

29 What is the hymen? What are the myths surrounding it?

From the Greek humen (membrane), the hymen is a ring of tissue around the vaginal opening. Contrary to popular belief, a normal hymen does not completely occlude the introitus (see question 30) but simply surrounds it as an annular structure. Hymens also can be septate (with one or more bands across the opening) or cribriform (completely stretching across the opening, but with several perforations). After pregnancy, they are usually reduced to a few remnants around the vaginal opening or to a ragged and irregular outline. Yet completely intact hymens have been reported after delivery. They also have been reported after intercourse. In fact, bleeding may not occur at all after the first vaginal penetration, and if it does, it may not be due to laceration of the hymen, but to trauma of nearby tissues. Finally, the infamous straddle injuries of old (such as horseback riding or falling on the horizontal bar of a bicycle) do not traumatize the hymen.

35 What should one look for when inspecting the labia?

For warts (see questions 36 and 37), ulcers, masses, discharge, atrophies, and swellings. Note that yellow-white asymptomatic papules may occasionally be noted on the inner aspect of the labia minora. They represent ectopic sebaceous glands (Fordyce’s spots), like those seen in the mouth and penile shaft (see Male Genitalia and HEENT chapters). They are entirely normal.

B. Examination With Speculum—The Vagina

39 What is a speculum?

A metal (or plastic) tool that is used to hold back the walls of the vagina in order to visualize the cervix and collect specimens. Specula come as small, medium, and large, and all consist of a handle and two blades (or bills). Before using them, always practice with the handle mechanism, and always warm the blades with warm water. Never use jelly lubricant, since this may interfere with cytologic determination and gonococcal cultures (see questions 59–64).

42 When do you withdraw the speculum? How?

The speculum can be withdrawn once you are done with cervical inspection and Pap sampling. To do so:

1. Hold the blades open while releasing the screw (otherwise the blades might painfully close on the cervix).

2. Once the speculum is safely away from the cervix, allow the blades to partially close, so that you can still inspect the vaginal walls. Look for bleeding, ulcers, tumors; also note the amount, color, and character of any discharge.

3. Finally, as you further withdraw the speculum, allow the blades to close completely.

49 What is diethylstilbestrol (DES)? What is the vaginal appearance of women with prenatal exposure to it?

C. Examination With Speculum—The Cervix

60 Which patients benefit from regular Pap smear screening?

Mostly two groups of patients:

Women who are sexually active (since they are the ones mostly at risk for HPV infection). They should undergo vaginal Paps either yearly or biennially.

Women who are sexually active (since they are the ones mostly at risk for HPV infection). They should undergo vaginal Paps either yearly or biennially.

Women who have had hysterectomies for malignant disease. Conversely, women who have had hysterectomies for benign reasons (such as myomata) no longer need Pap screening.

Women who have had hysterectomies for malignant disease. Conversely, women who have had hysterectomies for benign reasons (such as myomata) no longer need Pap screening.

D. Bimanual Palpation—The Uterine Corpus

66 What is the best way to examine the uterus?

Bimanually—a technique used not only to palpate the uterus, but also the adnexa (see questions 77–82). Prepare the patient by first lowering the head of the exam table to 15 degrees or flat, and by then having her lay the arms on either the chest or sides (which will relax the abdominal muscles). While standing next to the patient, insert then the gloved middle finger and forefinger of one hand (usually your right) into the vagina, in a downward and posterior direction, with gentle pressure toward the posterior fornix. Try to avoid the periurethral area. With fingers half in, rotate your hand 90 degrees clockwise, so that your palm faces upward, the thumb is extended, and the fourth and fifth fingers are pushed against the palm. Continue to insert the fingers into the vagina until you reach the cervix. At this point, palpate the vaginal walls and rugae, looking for nodules, scarring, and induration. Also assess the cervix for configuration, consistency, and tenderness. Once done, place your other hand (usually the left) on the abdominal wall, starting from the umbilicus and moving downward to the symphysis. Reach through the wall for both the uterus and adnexa. Use your vaginal hand to push the pelvic organs up, making them accessible (and palpable) to the abdominal hand. Note size, position, configuration, consistency, and sensitivity of the uterus. Remember that throughout the exam you should keep your eyes on the patient, looking for any signs of discomfort.

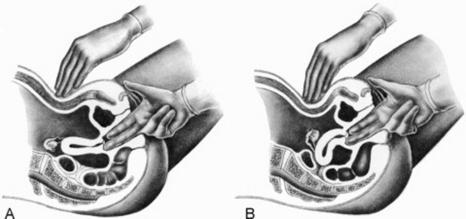

70 What is the difference between uterine retroversion and retroflexion?

Retroversion is a posterior angulation of the entire uterus, including the cervix. Retroflexion is a posterior flexion of the uterine corpus, while the cervix remains in its usual position. Both are normal variants, occurring in about 20% of women (Fig. 17-1).

E. Bimanual Palpation—The Adnexa

G. Rectovaginal Palpation

1 Bastian LA, Piscitelli JT: Is this patient pregnant? Can you reliably rule in or rule out pregnancy by clinical examination? JAMA 278:586–591

2 Bates B. A Guide to Physical Examination and History Taking. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott, 1991.

3 De Gowin E, DeGowin R. Bedside Diagnostic Examination. New York: Macmillan, 1976.

4 Frederickson HL, Wilkins-Haug L. Ob/Gyn Secrets. Philadelphia: Hanley and Belfus, 1997.

5 Mayeaux EJ, Spigener S. Epidemiology of human papillomavirus infections. Hosp Pract. 1997;15:39-41.

6 Moore K. The Developing Human. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1982.

7 Pearce KF, Haefner HK, Sarwar SF, et al. Cytopathological findings on vaginal Papanicolaou smears after hysterectomy for benign gynecological disease. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1559-1562.

8 Robbins S, Cotran R. The Pathologic Basis of Disease. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1979.